CONTEMPORARY FIGURATIVE ART may owe more to the golden age of comic books than many art watchers are prepared to admit. Beyond the ironic appropriation of comics by late art-world A-lister Roy Lichtenstein or au courant nihilistic punkster Raymond Pettibon, illustrated narrative has a much longer pedigree. Earlier in the twentieth century, the angular and planar paintings of pioneer American modernist Lyonel Feininger had their antecedents in the wind-blown landscapes haunted by nature spirits he drew for Wee Willie Winkie’s World—a color comic strip that appeared in the Chicago Sunday Tribune from 1906 to 1907. Who knew?

The artists just mentioned either parodied, subverted, or abandoned comics, and little of the positive populism of the medium was retained in their work. Not so with others, who came to fine art because they were first entranced by the dynamic figuration, transparent emotion, and vigorous narrative of comics. The use of comic book or cartoon sensibilities as springboards to other levels of figuration is worth noting. After WWII, when abstraction and expressionism rose to dominance, followed by physically diminished conceptual art in the 1970s, artistic training grounded in figurative drawing underwent a dissipation. This, however, didn’t discourage young artists interested in the drama, dynamism, and carnal presence of the human figure, whether drawn, painted, or sculpted. In their quest for instruction on the figure’s potential, they sought sources apart from the academy. A number of aspiring artists looked to comic book illustrators—commercially trained artists who labored under rigorous press deadlines and the expressive constraints of sequential panels. Only the most resourceful of artists could draw compelling figures under these circumstances, a fact not lost on artists who came to respect the supposedly lowbrow medium.

Cindy Jackson came to California from Saint Louis in 1986 to study figurative art after a brief career in graphic design. The impetus came while interviewing applicants to her design firm, when she was bowled over by the virtuoso portfolio of a young female artist recently graduated from the Art Center College of Design (ACCD) in Pasadena. Jackson recalls being especially taken with the artist’s facility in drawing and painting the figure. The result was a Damascus-like epiphany: I want to do that; I believe I can do that. Shortly thereafter, she applied to the ACCD and, on the basis of her graphic design experience, was awarded a scholarship.

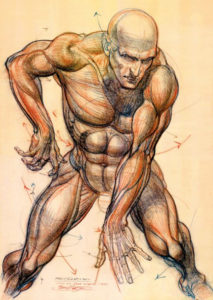

Returning to school at twenty-four, Jackson shifted to illustration after a semester. At ACCD, she encountered the legendary artist of Tarzan comics, Burne Hogarth, regarded among cartoon cognoscenti as the Michelangelo of the comic strip. Unable to enroll in Hogarth’s anatomical drawing classes because of the terms of her scholarship, she recalls peeking into his classroom, enthralled by his command as a draftsman and his theoretical system for constructing dynamic figures without referring to a live model. (His series of instruction books—Dynamic Anatomy, Dynamic Light and Shade, Drawing Dynamic Hands, and so on—has gone through several editions and is still in print.)

But Jackson held back from adapting Hogarth’s robust, mannered style to her own painting, which she recalls as largely “academic and accurate.” Six years after enrolling at ACCD, she began exploring sculpture, again working to exacting representational standards. While this suited her clientele, including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, for whom she made reproductions of famous sculptures, she felt a growing need to create a corpus of work that was truly hers. By reckoning with the human body, she wanted to develop an emotionally engaging narrative enacted by the figure. This desire, however, had to wait more than twenty years for fulfillment. When her daughter left home for college, Jackson found the space to realize long-incubating ideas—something akin to the creative freedom described by Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own.

§

Cindy Jackson is the younger of two daughters of a rural southern-Illinois Pentecostal evangelist who had a profound conversion experience as a Marine sergeant in World War II—an event he took as a call to the ministry. Postwar, small-town, tent-meeting Christianity was nothing if not patriarchal, and his wife and daughters were pressed into service. Since her older sister had already claimed the piano, Cindy was “forced to play the organ,” she recalls.

To find a creative outlet that was distinctly hers, Jackson turned to drawing, a practice her parents viewed with suspicion. The model at hand was Norman Rockwell; her family owned a book of his illustrations, which sprang from a reassuringly wasp socially conservative milieu. Rockwell’s ascendancy occurred in the golden age of American magazine illustration. His work was anatomically skilled, compositionally sophisticated, smart in forwarding a concept, and unabashed in its emotion. His instinct for his audience’s sentimental sweet spot was unerring.

Jackson has been candid about the contradictions of her blue-collar Pentecostal background. She came to see that many of the modestly educated hardscrabble folks in her father’s church were the “kissin’ cousins” of the resentful whites Barack Obama described in 2008 who “cling to guns or religion or antipathy toward people who aren’t like them.” As Jackson matured, she was dismayed at the reflexively defensive and diminished Christianity of her father’s congregations, their easy recruitment into the culture wars, as well as their sexism and racism.

One thing she remains profoundly grateful for, however, is her father’s work ethic. He supported his ministry with his carpentry skills, mastering tools and materials, taking pride in work well done and offering gratitude for it. He passed this ethos on to his daughters, who became confident with technique as a means of getting results. Indeed, it was this solution-oriented determination that steered Jackson toward graphic design, a discipline she wryly calls her gateway drug to fine art. In California, it was her post-ACCD apprenticeship of molding and casting figurative sculptures in the 1990s and early 2000s that planted the seeds for the comprehensive sculptural environments she would make later. Her first opportunity abruptly blossomed in 2010.

That year, the Babi Yar Park and Cultural Landscape Foundations issued a request for proposals for a sculptural monument for Babi Yar Park in Denver. Constructed in 1982, the twenty-seven-acre memorial park was designed by architects Lawrence Halprin and Satoru Nishita to commemorate the victims of the Nazi slaughter of Ukrainian Jews and others in a ravine on the outskirts of Kiev. On September 29, 1941, Nazi forces overseen by the notorious Einsatzgruppen ordered over thirty thousand Ukrainian Jews from war-ravaged Kiev to assemble for “resettlement.” Once gathered, they were marched to the Babi Yar ravine outside the city. At the site, their belongings and valuables were confiscated, and men, women, and children were told to remove their clothing. They were then systematically herded into the ravine where they were shot in waves, their bodies piling up in layers as the slaughter moved to its gruesome culmination. The Nazis photographically documented the mass extermination, and when the two-day killing was complete, they filled in the ravine with earth. Over the following two years, an estimated hundred thousand people would be killed at Babi Yar. Soviet troops, retaking Kiev in December, 1943, discovered the mass grave.

Absorbing herself in the historical circumstances of the atrocity, Jackson conceived an emotionally immersive sculptural memorial that would transform the grisly ravine of 1941 into a fourteen-foot deep, gently-sloping bowl. Measuring seventy-five feet in diameter, the bowl would be bisected by a concrete walkway, allowing park visitors to walk down into the depression and out again on the far side, returning to the grassy surroundings. As visitors traversed the footpath, they would gradually recognize that the interior of the bowl is composed entirely of a teeming web of nude figures of men, women, and children. These are modeled in high relief and in dynamic postures of yearning and struggle—no corpses here. Through Jackson’s ingenious design, the Babi Yar Monument would be sequentially experienced not only in the journey down and through the bowl, but by constantly having to look left and right, up and down, at the entwined and struggling figures. (Coincidentally, this feature happens to parallel the visual dynamics of comic book illustration, with its shifting sequences of close-up, mid-range, and distant views. For more on this, see Will Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art and Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative.)

Jackson’s audaciously vibrant vision recalls the array of twisting figures in Auguste Rodin’s monumental relief sculpture Gates of Hell (1917), and revives the sculptural tradition of striving, intertwined humanity upheld by the unjustly neglected Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland (1869–1943).

Alas, Jackson’s proposal was not commissioned; it proved more ambitious than what the two foundations were prepared to sponsor. Her monument did catch the attention of the US-Ukraine Foundation, and this led to interest in constructing it on the actual site of the slaughter, but the idea stalled in 2012. The Holocaust has always been a touchy subject in countries that once lay between central Europe and the Soviet Union. Many people were complicit in the killing of Jews, and post-Soviet governments have often denied or swept evidence of this under the rug. Even if Jackson’s Babi Yar Monument should find a sponsor, its unabashed and panoramic incarnation of the victims of the slaughter—the largest mass killing in the war—may be too unsettling for the public.

Undaunted, Jackson returned to experimenting in her studio. Among the first works to express her new direction was Yo-Yo Man. The piece originated as a sight gag: in early versions, a nude female dangles a nude, muscular, tightly coiled male from a string, as if playing him up and down. Wisely, the artist realized that the male figure held sufficient drama alone, and would pack a wallop if sculpted at twice life size. When Yo-Yo Man was suspended in a gallery setting, the clenched, cold-cast bronze figure with its grim gun-metal patina dominated the surrounding space.

Stylistically, Yo-Yo Man expresses the coiled force of Burne Hogarth’s drawings—punched up by enlarging and detailing the hands and feet, thrusting the skeleton through the musculature, and tracing arteries on the surface of the taut flesh. Such features are the lingua franca of comic book superhero anatomy. Jackson wrapped the axle of her bisected figure with industrial rope, prompting an unsettling association with a gallows. Despite its goofy title, Yo-Yo Man is nothing if not an existential symbol—he bears art-historical similarities to the tragic nudes in Michelangelo’s mural of The Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel and to those undergoing psychologically inventive punishments in Hieronymous Bosch’s paintings of hell.

The physical power of Yo-Yo Man encouraged Jackson to produce the work in multiples, molding them in papier-maché from her clay model. She floated twenty differently decorated versions in a three-story atrium as part of a city-wide art event in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 2012. This gave her the idea of installing single pieces as “interventions” in public spaces, where the disquieting figures re-contextualized or complemented their surroundings. A flesh-colored version hung mournfully above the barren, concrete-lined Los Angeles River; a black and white, Day of the Dead-like skeletal rendition hovered in the Metro bus shelter in front of the La Brea Tar Pits (an archaeological boneyard of Ice Age animals); another, layered with spray-painted urban graffiti, dangled behind the plate-glass façade of a mid-town LA gallery; strollers in a wooded park were unsettled when they came upon a blue lace-patterned figure swaying from a trail-side tree; and so on. (The full series can be seen at Jackon’s website.)

Reflecting on her work for the Babi Yar Monument and the variations on Yo-Yo Man, Jackson continued to brood on sculpture as a setting for a powerful emotional engagement with the viewer. Increasingly, she was feeling the need to come to grips with her vexed Pentecostal background, the Christian cultural legacy, and aspects of American society that troubled her. This eventually led to her multi-figure, comics-tinged, melodramatic 2014 installation (Not Quite) Salvation, a quantum leap in her staging of figurative sculpture to create an environment. She later recalled, “It was my first chance to make an immersive installation over which I exercised complete control.”

Like her Babi Yar Monument, the artist conceived (Not Quite) Salvation along a straight axis, this time though a gallery interior. Alluding to church architecture, Jackson transformed the gallery into a nave culminating in a gold-painted apse framed by a false wall with a pointed arch. A length of regal red carpet extended from nave to apse. While the architecture was rationally ordered, the sculpture roiled with human unruliness.

To reach the apse, the viewer must run a gauntlet of six twice life-size, buff, overtly gendered nude men in a state of anguished rapture. They take Burne Hogarth’s dynamic anatomy and put it on steroids. Very much the opposite of discrete, self-contained figures anchored on pedestals, Jackson’s monumental men-in-thrall formed an intimidating tunnel (an extension of the arch just beyond) with their supersized arms and groping hands. Produced in lightweight urethane for ease in handling, all six of the guardian mega-men are cast from the same mold and hold identical poses. Under their discomfiting limbs visitors warily journey to the “chapel,” where more figures await.

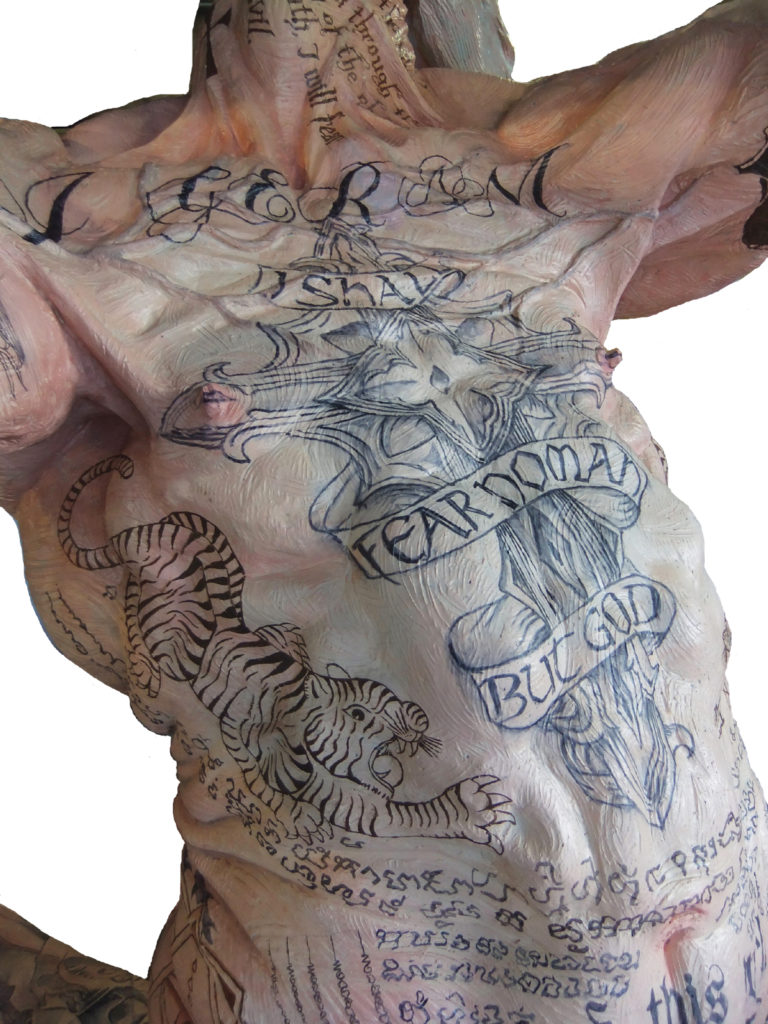

To distinguish the men, Jackson painted upon their skins “some of the archetypal and pop-cultural ways people seek salvation and comfort,” as the art critic Shana Nys Dambrot observed. I also see them as caricatures of conventional American masculinity. Entering the muscular mélange, one is greeted by Beer Man, his body overlain in gaudy Budweiser twelve-pack packaging; opposite him is Tattoo Man, inscribed with numerous signifiers rendered meaningless in their careless amalgamation. Tattoo Man is Jackson’s critique of a lazy American pop pluralism run amok; he brings to mind Flannery O’Connor’s short story “Parker’s Back,” whose spiritually resistant protagonist resorts to repeatedly decorating his body with tattoos, only to realize “he had not achieved that transforming unity of being” he hoped for (until he selects his final tattoo, a Byzantine Christ with “all-demanding eyes”). Interestingly, the anthropological origins of tattoos are religious. In tribal societies, the body was inscribed with signs and images of divine protection to ward off hostile spirits.

The next duo-in-rapture are Super Man and Sex Man—an apt pairing. The former is a durable American male fantasy of righteous superpower, created in the Depression era by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the striving sons of poor immigrant Jewish tailors, both obsessed with fitness culture. Jackson’s Super Man is psychically overwhelmed by his fantasy persona—cultural kryptonite. Sex Man is the lustful libido of Super Man, a flesh-colored figure enflamed with lusty red highlights on his hands and genitalia. His penis is sheathed with an XXL condom. One is tempted to compare him with a certain political celebrity who feels entitled to barge into the dressing rooms of unclothed female contestants in “his” beauty contests.

Jackson’s final pair of figures is Dogma Man and Money Man, suggesting the unholy and peculiarly American blending of religiosity and financial success. Dogma Man seems to get at the smorgasbord of pop spirituality. In addition to the Torah, he is inscribed with words from the libretto of Mozart’s Requiem, the Qu ‘ran, the poetry of Rumi, and the lyrics of Leonard Cohen, Patti Smith, and Bob Dylan. Money Man’s raison d’être is evidenced by the total papering of his body in (photocopies of) dollar bills. Thoroughly lavished in lucre, he can never acquire enough of it.

Each of Jackson’s towering and tormented mega-men is veneered with a false persona, imposed by the self and/or American culture. They have betrayed their true spiritual identity and are damaged souls. Jackson affirms this by inscribing a hopeful poetic aphorism, from the Sufi mystic Rumi, on the invisible interior surfaces of each hollow figure: “The wound is the place where the light enters you.” These words imply that spiritual grounding is attainable only when the sufferer acknowledges the injuries inflicted by his false persona and begins to nurture his inner life, the locus of genuine illumination. Having run the gauntlet of the mega-men, the viewer is prepared for what takes place in the gilt apse beyond.

Two entwined figures violently grope and thrash about on an altar-like pedestal, evoking the most flamboyant compositions of late-nineteenth-century French Romantic sculptors like Jules Dalou and Emmanuel Frémiet. And what is all the flailing about? Dambrot writes, a “man and a woman [are] covered in Gucci and Louis Vuitton designer logos, appearing to be wrestling or perhaps writhing in angst-addled psychic pain. Unlike the mindlessness of the worshipful tactics of the Men, these figures experience a more acute sense of torment, loss, and unfulfilled, misplaced desire—for the superficial, retail-brand things that people so often seek instead of inner peace.” Indeed, the work is titled Always Wanting/Never Enough, and it offers a sharp critique of our tendency to be caught up in competitive consumption, that is, attempting to attain social status through the products we acquire. In so doing, these figures have relinquished their human identity in favor of the logos of luxury: they’ve been branded.

What is Jackson doing by placing her agonized tableau in the sacred space of the gilt apse? Is it only to show that her two struggling figures are being sacrificed on the altar of consumerism? Once in the apse, viewers also notice two smaller figures suspended from the ceiling by chains and electrical cords: Falling Jesus Swag Lamps. This Jesus is posed as if for the descent from the cross and is rendered classically, rather than in the exaggerated, comic-book style of the mega-men. Departing from naturalism, Jackson has pasted a shimmery, clinging tulle to the bodies of her Jesus figures—one in gold, the other in silver—underscoring the pricelessness of the figure they adorn. Most art historical depictions of the descent from the cross are of groups, usually including the grieving Mary, Joseph of Arimathea, and assisting apostles, but Jackson shows Jesus alone. His body appears as if dropped from above. Is this some kind of irreverent joke? No, Jackson’s swag lamps were preceded by a somber bronze study, Falling Away, where a nude woman lovingly embraces a dead man as he gradually slips from a platform—Jackson’s version of the Pietà.

Complementing the interior inscription on her suffering mega-men (“the wound is the place where the light enters you”) Jackson has placed tiny LEDs in the stigmata on Jesus’s palms and torso, so that his wounds glow. The light of divine sacrifice and surrender exits him, shining on the desperately entangled couple of Always Wanting/Never Enough. In light of the Falling Jesus Swap Lamps, the chapel grouping becomes religious iconography for redemption from the snares of a desperate consumerism.

Perhaps as a visual hook to lure passersby off the sidewalk and into (Not Quite) Salvation, Jackson installed another line-up behind the gallery’s glass façade: a row of lurid, over-life-size sculpted heads mounted on stainless-steel poles, Seven Deadly Sins. Drawing upon Hogarth’s robust physiognomy of the skull, Jackson slightly altered each head to display the character of its transgressions. Anger, forehead veins bulging, bares his teeth; Lust sticks out a lascivious crimson tongue; the countenance of Greed is inscribed over and over with the word “more”; the eyes of the lime-green head of Envy shift covetously; the cheeks of Gluttony are stuffed with food; Sloth, the proverbial couch potato, has miniature television monitors for eyes and is crowned with an antenna; and the chrome yellow Pride embodies spiritual arrogance. Mounted on the tallest pole, whimsically haloed with a fluorescent tube lamp, a four-pointed star blazing from his forehead, Pride sneers at the world from his superior roost.

Though it was presented in an off-the-beaten-path nonprofit art space—Gallery 825 in mid-town Los Angeles—(Not Quite) Salvation may have been the most ambitious figurative sculpture project in Southern California in years. Visitors encountered a program that delivered mobility, contingency, and confrontation. Jackson’s combination of satire and reverence, her balancing of populist, critical, and spiritual components, created a memorable and immersive environment.

Often, an artist who undertakes a gesamtkunstwerk (a comprehensive work of art that combines numerous ideas and forms to make a total statement) can become physically and psychologically exhausted afterward. With what could Jackson follow (Not Quite) Salvation? As it turned out, the artist had a backlog of ideas and began experimenting with them by modeling figures in clay. She also found herself ready to commit to a promising personal relationship and relocated to Claremont, a leafy academic community thirty miles east of Los Angeles, where she re-established her studio.

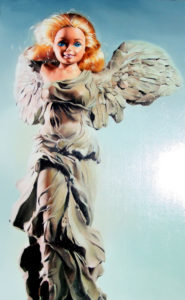

Jackson had taken some ribbing from colleagues for the über-masculine (Not Quite) Salvation, and she decided to focus on women in her next big project. The depiction of women in mythology and art history has long fascinated her, and while she identifies as a feminist, she prefers satire to direct argument. Perhaps with a nod to Marcel Duchamp’s irreverently defaced Mona Lisa (L.H.O.O.Q.), Jackson repurposes the most revered of Greek sculptures, the Winged Victory of Samothrace. When the marble statue of Nike, goddess of victory, was unearthed in the nineteenth century, she was missing both arms, one wing, and her head. But these losses only served to emphasize the dynamism of the deity, a wind-blown figure perhaps intended for the prow of a warship. With her own Nike sculpture in clay under way as I write, Jackson is drawing on her earlier painting in which Nike is re-capitated with the head of a Barbie Doll. With a wink, Jackson’s uncanny combination succeeds in transforming Barbie from a plaything to a victorious figure of strength and joy in a culture that tends to sexually objectify her.

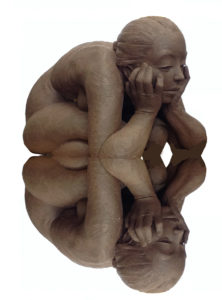

Jackson’s next sculptural environment was a revisionist gallery of iconic female figures from western art. Its title, Dancing Odalisques and Other Liberations, declared her goal of “re-introducing them into this current timeline of art history—with a few playful tweaks.” Again drawing upon classical mythology, Jackson feminized the figure of Narcissus, a hunter known for his selfish beauty. The offspring of the river god Cephissus and a woodland spirit, Liriope, Narcissus scorned all who offered him their love. Jackson picks up the story where, in her feminine adaptation, the huntress is getting her due from Nemesis, the goddess who meted out retribution to those who acted arrogantly before the gods. Enticed to a reflecting pool by Nemesis, Jackson’s Narcissus crouches over the water, utterly enraptured by her own reflection—condemned to a fixation upon her mirror image as she wastes away. In Ted Hughes’s translation of Ovid, Narcissus realizes his fate:

You are me. Now I see that.

I see through my own reflection.

But it is too late.

I am in love with myself.

I torture myself. What am I doing—

Loving or being loved?

…

That is my destitution.

Jackson’s sculpture-in-progress, Narcissus and Envy, is half life-size, and after it is cast from the clay model, she will apply a reflective chrome plating over its surface, fitting the work’s theme. A variation on Jeff Koons’s shiny super-sized balloon animals, Jackson’s blending of Ovid’s tale with contemporary bling hefts the kind of moral and satirical weight that Koons typically avoids. Think of it as a selfie in the round, with a bonus for the viewer, whose own image is reflected in the shiny surface.

The objectification of women in art history and contemporary society is a particular concern of Jackson’s. Feminist art historians have noted the role of the privileged male gaze. Paintings like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s 1839 Odalisque with Slave stoked the erotic fantasies of middle-aged bourgeois Frenchmen, offering the illusion of an exotic Turkish seraglio populated by languid, voluptuous blondes. Ingres arranges the nude, recumbent odalisque not the way an actual woman would rest, but rather for the maximum titillation of the male viewer.

With Ingres’s painting in mind, Jackson chose not to issue another scolding critique of the odalisque genre, but instead to subvert it. In the style of animated cartoons, she sculpted her own version of Ingres’s courtesan, risen from her couch and swaying to a melody that inspires her. Jackson’s notion of female agency—dancing for her own pleasure—is reinforced by producing her figure in multiples; a rockette-style chorus line of twenty odalisques will span a gallery wall. They seem a playful PG-13-rated sequence left on the cutting room floor of Walt Disney’s Fantasia. (A second odalisque is underway, derived from Ingres’s 1814 Grande Odalisque, who gives the male viewer a come-hither glance from her couch. Jackson’s version will feature two odalisques à la Ingres, who lie side by side, turning to eye each other with amused interest—tellingly disengaged from the male gaze.)

With her sculptural environments, Jackson activates the human form like few artists working in the medium today. Moreover, her grand-scale theatrical settings jar us out of the tame encounters we have come to expect from most contemporary art. This is just the sort of tonic we need; for too long, the avant-garde has been recycling itself, and too many galleries display art that, well, looks like art—camera ready. An artistry that springs from a sincere reckoning with our embodied condition—connecting us to tragedy, laying bare sin and redemption, challenging corrosive secular consumerism, or critically plunging us into art history, while seasoning these endeavors with a sophisticated populism and humor—all this seems too much to expect. Not so if its artist is Cindy Jackson.

The narrative potency of her sculptural environments may eventually find favor in the official art world. In the meantime her work will place engaged viewers in situations that, as she is fond of saying, “do not cause thought, but prepare us for thought.” Jackson has always desired to provoke us with ideas and images that take us deeper, and that will be quite enough.

As this issue went to press, Cindy Jackson lost her battle with cancer. Her work can be viewed at www.cindyjacksonsculpture.com. For more information about her sculpture, please contact Gordon Fuglie at gordon.fuglie@charter.net.