DUTCH-CANADIAN, of Midwestern Winnipeg, an ordinary follower of Jesus Christ. This is perhaps the most succinct way to situate the artist Gerald Folkerts. Readers may ask, “Can any artistic good come out of Winnipeg?”

Come closer. Take a look.

Winnipeg, Manitoba, is not like Bible-belt Alberta, but is hard-working Mennonite farming country. Under God-blue skies, its utterly flat, expansive plains of ripening grain are as overwhelming as the “America the beautiful” of the Dakotas, Montana, and Wyoming. Nothing fences you in except myopia.

The Canadian prairies are the original stomping ground of Metis Indians, immigrant Ukrainian Catholics, and the ubiquitous followers of Menno Simons, who fled persecution in Russia via Canada to South America. The cultural lay of the land is not Wild West, but Midwest. People come here to settle, raise families, do honest labor, and take their Sabbath rest, all far from the madding crowd. Also far from the established art center of Toronto, the avant garde beat of Quebec, and the theater-cinema-youth circles of Vancouver, not to mention the sophisticated “artworld” of New York City. Winnipeg today, a city of 640 thousand at the center of Canada, still has a rural feel and mentality. Here is an open-hearted small-town environment where hospitality is a native virtue.

A frank, homespun, and no-nonsense attitude toward art is rather unusual in the western museum world today, but Winnipeg is an exception. The well-respected Winnipeg Art Gallery was homegrown, not instituted from the top down as a provincial branch of the Royal Canadian Academy of Art. It began with the Manitoba Society of Artists, which grew to include an art gallery and school in 1912 and was incorporated by the legislature in 1923. The school’s curriculum was rigorous and rather Victorian in the early days, but it enrolled amateurs as well as art-career students, offered night classes, and undertook community outreach projects. This inclusive approach became a defining feature of Winnipeg’s official attitude toward artistry: “involving people in the visual arts” to enrich the populace at large.

§

After graduating in 1980 from Dordt, a Christian liberal arts college in Sioux Center, Iowa, with a degree in fine arts and education, Vancouver-born Gerald Folkerts went to Winnipeg to settle down, raise a family, and make a living. There he taught art and Bible courses to middle and high-school youth in schools allied with the Christian Reformed Church of North America. You need to be a husky, six-foot, four-inch tall fellow with a ponytail and survival skills to keep your imagination firing and discipline that age group as they draw and paint week after week, year after year. But teaching studio art to a younger generation is probably more allied with art-making, if that is your calling in life, than waiting tables in a restaurant. In the old days in Holland, Vermeer brokered paintings to earn part of his keep and let his mother-in-law pay the rest of the bills, while Jan Steen ran a tavern. It was not until 1988, when Folkerts’s wife Arlis, after bearing four children, found a consulting job trouble-shooting for the Manitoba Department of Education, that Folkerts could start doing art full time.

During these early years Folkerts made many drawings. These meticulous, time-consuming one-off pieces offer carefully composed graphic narratives. As when you tell Bible-stories to children, when you draw in pencil, you highlight details that fascinate and make the main points memorable.

A Double Portion (1987) shows Elijah being tornado-funneled up to glory in a fiery chariot with flaming horses, finishing his earthy stay tumultuously, the way he lived it. The planets and stars through which he passes twinkle like little Christmas tree ornaments, and the big black ravens God once used to feed the discouraged prophet fly ominously below, like huge bombers over the curved face of the earth. Scrawny Elisha stands there, before a Hokusai wave through which he must pass, seeking a blessing, ready to catch Elijah’s fallen mantle. The whole complex scene is rendered in a straightforward fashion. The extraordinary incident is pictured with simple wonder but without mystical intimations. Heaven and earth are of a piece to the eyes and consciousness of a believing child.

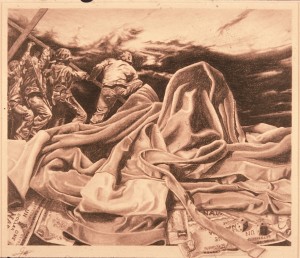

Good Friday (1989), another graphite piece from this early period, is storytelling for grownups [see Plate 6]. In imitation of the famous (staged) raising of the American flag on Iwo Jima during World War II, Folkerts’s drawing shows the iconic soldiers raising instead of the flag, a cross. Dark, rocky soil occupies the background, while the foreground is filled with a close-up of the disheveled, seamless tunic Jesus is said to have worn. Dollar bills lie beneath the huge garment, and a pair of thrown dice rest upon it, showing snake-eyes. It doesn’t take too much pondering to sense the banality of evil here. Soldiers may die in worthy wars or do the dirty work of unjust governments, but the professional military life is mostly boring and sordid. While the soldiers are American, the dollar bills are Canadian. Like a morality play, the piece quietly implicates everyone who condones violence, any country that exports weapons, as complicit in the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

The early drawings are a tour de force in pencil. The fact that they tell stories does not make them illustrations. A good illustration is worth its salt, too, but there, artistry is willingly subordinated to the literate communication it accompanies, enhancing and complementing a text, like a poster. But in my book only a drawing which tells a story by itself, like a song without words, which keeps the graphic note uppermost so the tale stays ambiguous, musters the imaginative cachet to qualify as art. You don’t need an allegorical overlay to convert a heap of linen cloth into art. In portrait, Christ’s soiled tunic, its twists and turns, modulated fuzzy grays, shadows and whites, sits at center stage like a memento mori, whispering of death.

At the time Folkerts made these drawings, narrative graphic art was out of fashion. In the fifties, New York critic Clement Greenberg had been influential among mainstream Toronto artists, and in Canada the New York School was promoted as a progressive trend one could be part of in order to avoid parochialism. In the late seventies while visiting Toronto, Greenberg still intoned ex cathedra that any serious artist had to go to New York, where the real action was. Folkerts missed all this overly serious art-school fervor. He came out of a good Christian liberal arts college milieu and was content to tell stories with a pencil. He did not have to come to terms with a lot of fashionable art-school baggage and could simply make drawings about what seemed important to him. It’s a bit like not needing to decide whether to write poems like T.S. Eliot’s footnoted “Wasteland” or “Howl” with Allen Ginsberg: you just compose soft-spoken verse like Emily Dickinson.

Another drawing, Mama, Waar Bent…? (Mother, Where Are You?) (1990) spotlights a little child entering a huge, dark barn looking for his caregiver, who has hanged herself from the broad wooden beam which holds the barn walls together. The carefully drawn horizontals and verticals and vanishing-point perspective tone the melodrama down to a gripping rural tragedy. Like Robert Frost’s “The Death of the Hired Man,” Mama, Waar Bent…? is unmistakably regional, but it reaches out and touches humanely whoever has known hardship and loneliness. Art that is locally rooted but universal in its awareness of life’s troubles has been a hallmark of Winnipeg’s tradition over the last century. Folkerts’s painstaking early work found a cultural home in this regional setting.

§

The Fred Reinders Consultant firm, when it remodeled a high-rise apartment building in Edmonton, Alberta, into the King’s College campus, believed that artwork was part and parcel of educational construction. So for the building’s interior they generously commissioned a series of Folkerts’s paintings dealing with the creation of the world. Folkerts called it the Alpha series, eight oil paintings on mahogany panel, each four by four feet, one for each day of the biblical Genesis account (and one before the creation began). Quite naturally the topic led to nonrepresentational work, since the primordial chaos does not have much of a contour, even after it is illuminated by God’s command. And it takes ingenuity to picture the mess of waters separating into manageable clouds, seas, and rivers, while the earth brings forth vegetation, colorful flowers, ganglia of cells, spermata, bacteria, and creeping creatures. Only with the creation of humans—Folkerts inscribes his own naked form on the face of one of a scramble of toy blocks in Alpha 6—do we approach perceptible formed objects. Alpha 7 portrays someone resting in a stuffed green armchair, reading a book entitled Wonders of the World, celebrating the Sabbath and the feat of God’s alpha Word in action.

This commission was important in Folkerts’s development. First of all, it was a vote of confidence that he could provide professional quality art and be paid a fair price for his labors. Second, the idea of a series honored his bent for narration, while giving him time to depict the meaning of different connected events. Third, it led to his trademark brushstroke of oil-paint dabs, chips, and jumbled slabs (done with a brush, not a palette knife) somewhere in between German Expressionism and Seurat’s pointillism.

Plate 7. Gerald Folkerts. Study for Alpha 3, 1992. Oil on panel. 9 x 12 inches. Photo by

Gerry Wyenberg.

As Study for Alpha 3 (1992) shows, the painting is composed of deliberate strokes loosely juxtaposed [see Plate 7]. The colors seem at first to be placed randomly, but you soon sense that the strokes are intuitively ordered. A couple of plant shapes materialize. We see leaves, sunlight. Definite planes, panels of color, and segments guide the viewer’s eyes. The whole is pleasantly geometric, but with an organic feel. There is little buildup or layering of applied paint. The spots of yellow and green are like raindrops, petals, and reflections, while the darker orange and brown are earthy. The unreworked, splattered character of the dabbed paint provides excitement and brightness to the whole, so you tend to overlook the minute attention each piece of brushed paint demanded.

What strikes me about Folkerts’s pieces is the workmanship in evidence, but also the playful qualities of surprise and elliptical reference. I take art to be a well-crafted artifact or act distinguished by an imaginative quality whose nature is to allude to more meaning than what is visible, audible, written, or sensed. For me, the first requirement of artistry is skilled formation in a medium (paint, voice, words), and the last requirement is a subtle quality which permeates the whole object or event with an engaging metaphorical coagulation of nuances. The first requirement keeps fine art related to artisanship. The second asks that the defining imaginative nuancefulness be embodied, ingrained in the object, that it inhere the enactment itself, rather than be merely attributed to it by a reacting subject. Folkerts is a master of this ordinary artistry. His no-nonsense approach to his materials is deeply engrained in the artifacts he creates, with their pluri-suggestive meanings. Here is no metaphysical gasconade with a pretentious title, no hint of a literary analogue: it is simply A Study for Alpha 3, a laughing, earthy burst of colored paint that breathes organic life.

§

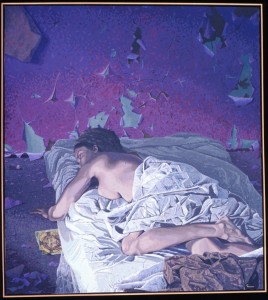

After Folkerts was able to devote himself to painting full time, he produced a series of good-sized oil paintings, Restless Slumber (1999-2002). These works delve into a deeply human phenomenon that is also shared with animals and even plants. Shakespeare’s Macbeth calls sleep “the death of each day’s life, sore labor’s bath / balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course / chief nourisher in life’s feast.” Folkerts’s own analysis of the series is this:

Restless Slumber is a body of work in which sleep is used as a metaphor to probe the uneasy tension between providence and what humanity experiences on a daily basis: life’s vulnerability. Personal experience would suggest that each of us is one death, one sickness, one lost job, one encounter with brokenness away from living in a wilderness of despair where all that once suggested stability seems shallow and insecure. Restless Slumber is an attempt to explore and contemplate the brokenness that exists within each of our own realities…. Through the portrayal of sleeping figures, the Restless Slumber paintings probe the tension between our longings (to be safe and secure) and what we know (that brokenness is inescapably part of life).

An early painting in the series draws on the nuclear disaster that took place in the Ukraine in 1986—Chernobyl Nightmare (1999) [see Plate 8]. Working with a model, Folkerts portrays an unclothed woman asleep on a cot under rumpled sheets. The paint on the shabby walls is blistering because of past nuclear heat. The purple shadows on the woman’s exposed back, arm, face, and legs do not look healthy. Her hand seems to grasp the gravel floor for support—or is she reaching for the little bottle of pills? An Orthodox icon of John the Baptist lies on the floor, half under the mattress, perhaps for nightly prayers—a rather wan token of protection. The air is deathly still. The sense of the woman’s vulnerability is overwhelming. She is asleep alone, “dead to the world,” unsuspecting of lethal invisible particles in the air. The painting’s balanced design, the lack of any climactic focus, the overall dull purplish and gray coloring, the collapse of background into foreground—all contribute to an aura of stillness, of being forsaken, forgotten by everyone—except the artist, who caresses the supine figure with care, remembering the disaster by quietly noticing the aftermath, well after the media have gone on to look for more headlines.

Folkerts writes:

I believe it’s exactly in the kind of world in which we live today that God calls God’s people to artistic faithfulness with a renewed sense of urgency, because our art may be (certainly not by itself!) one significant ingredient in a soothing ointment that God would use to heal the aching wounds which fester deep in the very heartbeat of a world that more often looks to economics, science, and technology for some kind of salvation as it teeters on the edge of despair.

The Restless Slumber series ranges far and wide as resolutely figurative art. Just as rhyme and rhythm give a level of density to formal poetry that is not available in blank verse, human figures in paintings allow viewers—if they take the time to look imaginatively—to reach for deeper resident meanings, it seems to me, than can be offered in, for example, color-field painting or optical art. Good figurative art is people-friendly and draws a viewer into what Pascal called “the glory and misery of humans” in God’s world.

Anniversary #31 (2000) is an amazing tribute to faithful marriage. A diptych of two four-by-four-foot canvases shows in close-up the sleeping heads of a husband and wife, each in a separate panel, he wearing a grotesque sleep-apnea apparatus, and she curled, fist to her cheek, also in deep sleep. The air cable from his machine, like a convoluted green snake, joins the diptych in the background and coils around her neck. A ghastly purple hue delicately saturates the scene. Indeed, thirty-one years of sleeping together is a commitment made for better and for worse. The utterly unromanticized, true-to-life exposure of human intimacy touches, astounds, causes a double-take. This is nothing like Francis Bacon’s angry, slashing disfigurement of the human form. Instead, like the wise man of Ecclesiastes, the painter gently picks up the pieces of human travail.

Weariness brings on sleep too, as an impressive four-by-five-foot canvas titled Unfinished Business (2000) shows. This is an art painting about the manual labor of paint-roller painting—in fact, of painting over an old wall. The tall, tired worker in this self-portrait sleeps somewhat precariously on a board supported by two ladders. The job is not done. Under one of the ladders lies an overturned bucket of yellow paint, making a mess. But the painting is carefully ordered, every angle of the shadows calculated. Folkerts’s style is too forthright to be ironic; the overturned bucket emblem is more epigrammatic than ironic. Don’t cry over spilled paint, it seems to say. Clean it up, and keep working. The image of the sturdy lone worker in his fatigue seems close to the spirit of Matthew’s Gospel: “Well done, good and faithful servant; enter into the joy of your lord.”

Two of the Restless Slumber series deal with dreaming, that private fold of consciousness in which we wrestle with fears, desires, and memories unresolved in waking life. The smoking, flaming fires in The Watcher (2001) immediately catch the eye. Then you see the dark, silhouetted figure of a man. His back to us, he leans on a shovel, watching the many backfires he has set to control the burning of the acres of farmland he faces. In the darkened foreground you notice a reclining, naked, full-breasted young woman. She is not quite a pin-up girl, also not quite real; she is, however, an erotic presence behind the back of the man watching the field of fires; he does not look at the largest fire closest to the vulnerable woman. It is an intriguing painting, both accepting and critical of the way erotic desires can run wild in men. The placement of the shovel handle in relation to the woman’s body is not accidental. The vivid jumble of nervous brush strokes—full palette—energizing the furrowed fields, burning embers and flash fires, seem to engulf the stolid, grim, silhouetted man in a graphic ancient proverb:

Can a man take fire in his belly and his clothes not be burned?

Can a man walk on burning coals and not have his feet roasted?

§

Folkerts was elected president of the Manitoba Society of Artists in 1999, and began to win first prize in their annual open juried exhibitions with embarrassing regularity (in 1999, 2002, 2004, and 2006). You become a professional artist, I think, not so much when you have an MFA in hand as when you can play with the fundamentals of your task and consistently produce something worthwhile. A good amateur can upon occasion throw a strike, while a professional comes through with solid results even on bad days. The Restless Slumber series testifies to Folkerts’s hard-won credentials.

Waiting for Eternity (2002), the last painting in that series, is an exceptionally strong, painterly piece in which vigorous underpainting seems to work toward a practically monochromic amber color [see Plate 9]. An almost life-sized figure is caught diagonally, as if running a race, suddenly entangled in a web or resinous netting. The inert person is enmeshed—embalmed, you could almost say—in the fabric, a kind of friendly winding sheet, since the painting does not have an ominous cast. It is not as if prey has been trapped, more as if a treasure has been saved, protected, and reverently stored. A fitting comment would be the Apostle Paul’s remark to those who were confronted with the upsetting fact that believers in Jesus Christ’s resurrection power apparently still died: “Don’t worry,” he wrote to the Thessalonians. “They are just sleeping.” And that aura of security and peace does emanate from the work.

A companion piece to Waiting for Eternity is a little nonrepresentational construction entitled Half-moon Dance with Ball and Chain (2002) [see Plate 10]. Each of the ten large paintings in the Restless Slumber series has a small, complementary, nonfigurative painting next to it, composed of the palette pigments left over from the main painting. What started out, in good thrifty Dutch fashion, as a way not to waste good paint became a way for Folkerts to fool around imaginatively and loosen up the tightness of his usual style. Folkerts thinks these abstract offerings are where his personality shows up most clearly. I myself see them as wholesome attempts to exhale, to come up for a breath of fresh air, to laugh out loud a minute before continuing to grapple with what is at stake in God’s troubled world: life, or death.

Half-moon Dance with Ball and Chain is a delightful contraption which looks like a tilted dance floor on which half-circles, outfitted with necklaces of beads, are crowded together like bumper cars at an amusement park, ready to dance and fling off their inhibitions. But the ball and chain are present as restraints. Viewers are encouraged to pull down gently on the ball, because the chain above is actually a spring. When one pulls, the whole dance floor is animated, and the necklaces pleasantly shimmy. The piece is a lovely memento vitae for anyone who feels shackled by killjoy customs of a faith tradition.

Folkerts’s current major undertaking is a series of large works called Head over Heels—as God is head-over-heels in love with us human creatures. Only heads and feet are painted, sometimes in diptych or triptych, at other times as a single canvas, in vivid, sometimes even lurid dashes of brushed color. The faces and bare feet (or in some cases, shoes) deftly set up in-depth character studies: a worn face and battered shoes tell a story. Folkerts’s portraits give voice to those who have trouble speaking, or to whom nobody else is listening.

Young Brendan (2003) holds a fistful of rocks in an alley; tangle-haired Timothy (2004) broods, drinking pop on a park bench, holes in the soles of his shoes; wrinkled Monty (2004) with bulbous nose, paint-splattered sneakers, and malformed feet waits to be hustled away; bedridden Toni (2006) suffers quietly, confined indoors; imperious garbage-picker Daryl (2006) stamps confidently through refuse in an ashen dump; pain-stricken Carol (2007) stares ahead unseeing; farmer David (2007) has been untimely pulled clean out of his work boots and is gone with the wind; wizened Richard (2008) presides in his wheelchair on a street corner. It is not a rogues’ gallery, but a generous tribute to a raft of outsiders, persons who for one reason or another do not fit into regular society. Each has been ostracized by antisocial behavior, sickness, poverty, a disreputable occupation, or a crippling handicap, segregated by who knows what fault or unfortunate event.

My favorite portrait is Ralph (2005) [see Plate 11]. His sorrowful eyes ask for commiseration and pity, and his scruffy shoes witness to his plight. But Folkerts’s artistry ennobles this homeless man, giving him the benefit of the doubt after hearing his story that his wife kicked him out of the house a half year ago: a glorious rainbow of lavish paint brightens the sad face, and the steam from the lowdown Tim Horton’s cup of coffee at his feet rises, hinting that perhaps Ralph, too, will undergo an assumption out of his miseries. Whether the poor fellow is culpable for his situation or a victim of complicated circumstances, Folkerts does not judge. Instead, he dispenses imaginative attention as a friendly benediction. Maybe this is what a professional artist whose wife brings home the bacon feels in need of, too.

In Head over Heels, it is as if the lone, fitful sleepers of Restless Slumber are now awake in the vicissitudes of daily life. The Head over Heels paintings offer their own graphic beatitude: Blessed are the derelicts and left out persons, for such characters are all unforgettable to God, they seem to say. And we respectable ones should not forget the excluded either; the outsiders, the leftovers of humanity, are not negligible. Folkerts visited and talked with each of these misplaced people on location. They are people with names, who deserve to be taken seriously as neighbors. These buffeted people can teach us that the Lord of the universe does indeed provide for his creatures through thick and thin, prosperity and poverty, wellbeing and woe. And as Paul writes to the Galatians, when you love your neighbor as yourself and shoulder your neighbor’s burdens—even simply by listening—you are fulfilling the law of Christ.

§

I find the vision of the world underpinning the work of Gerald Folkerts to be as large and inclusive, as sharp-sighted and relevant as the cosmos of the biblical psalms. There are fascinating sights, enigmatic histories, subtle temptations, untold possibilities, exuberant and sorrowful incidents to be noted—and these things can be taken by the faithful with a measure of equanimity. God’s providing care absorbs both tragedy and comedy. In Folkerts’s art, life is ruled not by struggle against failure, but acceptance of one’s lot. The very compositional design, the placement of configuring lines, the expressly chosen rainbow of colors all bespeak not resignation but a basic openness and trust that all things shall work for the good of those who please God. Backgrounds seem to coalesce with foregrounds. Figures appear close up, hiding nothing. All this gives a paradigmatic, quieting settledness to the stories being told, including the failures. Faith in God’s gracious sovereignty is simply normal in Folkerts’s artistic purview, unselfconsciously assumed as basic, not something to be worn like a badge or medal. That rooted confidence in God’s guiding hand gives a fundamentally reserved peace to all Folkerts’s work.

A loving, diaconal spirit permeates the drawings and paintings, an unobtrusive gratitude for the ordinary gifts of being human. There is no straining to elevate art into a vehicle for transcendence, to make it sacramental or give it liturgical overtones. The work’s aura is not narrowly devotional or meditational, but its spirit is one of reformation, deeply aware of both creaturely glories and societal shortcomings. But Folkerts’s work doesn’t preach. It remains oblique and allusive, though intelligible. This art does not reach for heavenly ecstasies or mountaintop experiences of the numinous holy, but is content to mitigate earthly sorrows with a painterly embrace, to spread grace upon earth through paint. Folkerts has the wisdom to let his Christian faith subtly percolate in his painting by showing compassion for his problematic subjects. In his work there is a quiet beguilement with the wonders of our world, plagued by troubles. As we look at these images, contemplating the restless sleep or anxious indigence of our neighbors, we ourselves may begin to take on the serious, gentle, non-judgmental, and perceptive approach of the artist.

A special mark of the oil paintings of Gerald Folkerts is their ordinary workaday grit, quite different from most current market-oriented fine art. Folkerts is not caught in any “modernist avant garde” versus “postmodernist potpourri” dialectic. Instead he lives and makes art directly out of the vibrant folk continuum of Canadian Midwestern daily life, somewhat as old Netherlandish Vermeer and Breughel did in Europe long ago. Folkerts’s art is not about art, but about neighbors, about the marvels and predicaments of our fellow creatures—thank God. Art is not important. It is what an artist does that counts: put paint on canvas to show that he sees and cares for what needs tending in God’s world. Folkerts’s ordinary, well-crafted paintings spill hope upon whoever looks at them attentively. They document the human burden in a way that is thoroughly unsentimental. From beginning to end, Folkerts’s drawings and paintings listen to those neighbors, giving voice to those who are unable or have given up trying to tell their hurts. It’s enough to make the angels around Winnipeg break into a canon of rejoicing.

§

Gerald Folkerts was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor in September of 2008. He became progressively more incapacitated and entered palliative care. Over the winter, Canadian songwriter and friend Steve Bell and Anglican priest Jamie Howison, along with Mennonite and Reformed community members, prepared an impromptu retrospective exhibition of Folkerts’s work at the Outworks Gallery in Winnipeg, and also produced a full-color catalogue. His friends expected this to be a posthumous honor, but Folkerts rallied and even attended the opening and closing of the exhibit in a wheelchair with his wife and extended family. Throngs of people visited the four-day exhibition—youth, the elderly, believers, disbelievers—and it was promoted by ChristianWeek, CBC television, and even the professed atheist art critic Morley Walker of the Winnipeg Free Press, who spoke up to ask for a miracle of healing. All this testifies to the power of Folkerts’s ordinary, neighbor-loving artistry, not confined to the sophisticated artworld. The event had the jubilant, crowded feel of a barn-raising picnic on the prairies. Those in attendance marveled at this foretaste of how, on the new earth, art will not be a precious commodity for gnostic contemplation, but an ordinary shared gift of joy that builds communion.