A Grant of the Divine—

That Certain as it Comes—

Withdraws—and leaves the dazzled Soul

In her unfurnished Rooms.

——————————Emily Dickinson

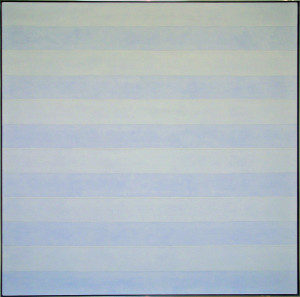

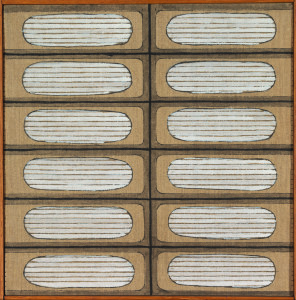

PLATE 6. Agnes Martin. Falling Blue, 1963. Oil and graphite on canvas. 72 x 72 inches. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Moses Lasky. All images © 2009 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society, New York.

PAINTER AGNES MARTIN, who died in Taos, New Mexico, in 2004, had the ability to make seemingly restrictive, minimalist forms pulse with life. Her paintings are nearly all made up of straight lines and squares—and yet these apparently rigid forms, varying in size and medium, provide her all the tools she needs [see Plate 6]. Early in her career, she painted grids in which each square was filled with dots, or even nail heads. In other works, freed from the constraints of a strict grid, she drew and painted horizontal bands, sometimes executing them extremely tightly, sometimes more loosely, drawing line after line directly on a lightly gessoed or painted background with a ruler. At a glance, the surfaces appear to have been rendered mechanically, but upon closer inspection, the evidence of Martin’s hand is everywhere.

Martin painted her signature linear and grid images by working from top to bottom, using a system of mathematically spaced dots at the top of the canvas to guide her. Later, she might fill in bands of color in acrylic paint (with characteristic humor, she once called herself “the queen of acrylic”). Here we can see the mark of her hand even at a distance; the lines have a softness, because Martin worked quickly to avoid drips in the fast-drying paint. Despite an apparently constrained format, the undeniable hand of the artist, in pencil or in paint, is one of the most poignant aspects of her work. Having seen one of her works, one longs to see others. Paintings of squares have never seemed so alive.

Fortunately, seven of her large, blue and white canvases are on permanent exhibition at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, New Mexico. Martin spent almost four decades in that state, and the Harwood’s Agnes Martin Gallery provides great insight into her oeuvre. The space offers a restorative and refreshing retreat from the messiness of daily life. Surrounded by orderly horizontal lines and peaceful blue and white pigment, one enters a kind of haven.

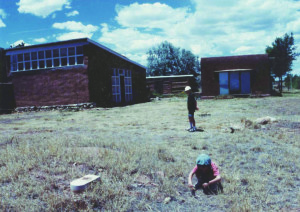

When Martin first returned to New Mexico after years of working in New York City, followed by a nearly three-year detour across North America in her camper, she initially did not paint at all. Instead she focused entirely on building houses—strictly functional shells for living and painting.

PLATE 7. Adobe studio and house built by Agnes Martin in Galisteo, New Mexico, beginning in 1977. Photo: Joanna Weber, 2000.

Though Martin never owned the land upon which she built, while in New Mexico, she built three living complexes with her own hands, each with multiple buildings, including one in Galisteo [see Plate 7]. In all three, she used traditional materials, making her own adobe bricks and transporting the large vigas (rafter beams) in her own truck. She poured straw and mud into rectangular frames and kept pouring until the bricks were all dry and ready to be laid.

Only after most of her second dwelling, this one in Cuba, New Mexico, was complete did she build herself a studio, a small bunker-like structure built into the ground to provide coolness in summer and warmth in winter. Slowly, through the time-consuming process of making and building with adobe bricks, Martin found her way back to painting, working at first almost entirely on paper.

§

Considered alongside her delicate paintings, the laborious manual process of house-building begs the questions: how are these houses related to her art, and are they sculptures in their own right? Before her death in 2004, I spoke with Martin about how much she enjoyed house-building. She claimed, however, that it had nothing to do with her art. What was important was her painting, she said, and neither her biography nor her other endeavors were relevant. Nonetheless, the spaces she created for living and painting demonstrate a keen interest in her surroundings—and I believe they offer a unique lens through which to view her art. Both painting and building with adobe are manual, deliberate, and progressive projects, with concrete end results. And the houses Martin made, like her paintings, were all grids of bricks and plumb-lines.

The Harwood’s Agnes Martin Gallery, which she helped design, might be considered her purest house of all: a house distilled down to its essential elements, a safe haven that also retains an uncanny sense of the presence of the Other. This “house” is a walled space, not for living or painting, per se, but for reflection.

Situated high in the New Mexico plains, at the base of the sacred Taos Mountain, the nest for the Blue Lake, the Harwood is a small museum exhibiting both regional and national artists who spent time in the area. The town of Taos was an active artists’ colony from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, home to artists including Marsden Hartley and John Sloan. Continuing this tradition in the latter half of the twentieth century were John Diebenkorn, Beatrice Mandelman, and Martin herself.

At the Harwood, which houses an extensive collection of works made in Taos over the past century, we find the only permanent display of Martin’s work for which a museum created a dedicated environment [see Plate 8]. In 1997, the museum completed an addition designed specifically to house her work, an octagonal space that is now home to the seven paintings, part of a series of ten made shortly after her arrival in Taos in 1992. Each is five feet square, acrylic on canvas, and hangs on a wall eleven feet square. The eighth wall, the entryway, offers the viewer a participatory role. At the center are four square yellow benches by Donald Judd, one of Agnes Martin’s many artist friends. Above is an oculus skylight.

The shape of the room finds an antecedent in the circular structures of Indian kivas, of which there are many examples in New Mexico, as well as fourth and fifth-century European baptisteries such as those in Ravenna, Italy. Among modern installations, the structure most resembles the Rothko Chapel in Houston. The Rothko Chapel strictly respects the octagonal shape so frequently used in those early Christian baptisteries, which itself refers to funerary architecture, and to the eighth day of creation, the day of resurrection—a play on death and rebirth through the waters of baptism. But while the Rothko Chapel evokes grief and turmoil, the Martin Gallery is affirmative, imparting wonder and launching us into a realm of reality which demands that we make joy a way of life. Here, time stands still, with a stillness both peaceful and full of energy. This space presents itself as a monastic cell, or studio, or both.

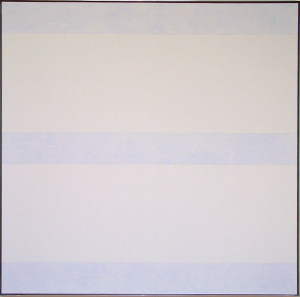

PLATE 9. Agnes Martin. Untitled (Friendship), 1993. Acrylic on linen. 152 ½ x 152 ½ inches. Collection of the Harwood Museum. Gift of the artist.

PLATE 10. Agnes Martin. Untitled (Perfect Day), 1994. Acrylic on linen. 152 ½ x 152 ½ inches. Collection of the Harwood Museum. Gift of the artist.

Martin herself selected the seven paintings from the original group of ten and arranged them in their present order, with the assistance of her great friend Bob Ellis, then director of the Harwood. When first installed, the paintings were untitled, but Martin named them in the spring of 2000. Beginning to the left of the door and reading clockwise, they are: Lovely Life, Love, Friendship [see Plate 9], Perfect Day [see Plate 10], Ordinary Happiness, Innocence, and Playing. The titles read as an abbreviated poem, and they provide a view into her intentions for each work and for all seven as a whole. While she did not name the installation itself, when people referred to the space as the Agnes Martin Chapel, she did not object.

Seven is the number of days in the week and of creation, and is the traditional number of completion or perfection, harmoniously connecting the body to the soul. It is also the number of mansions described by Teresa of Avila in The Interior Castle, a text that explores the search for perfection as a journey through a series of rooms.

On entering the Martin Gallery, we feel impelled first to experience the paintings as a group, then individually, then as a group again. At first one is struck by the similarity of the paintings. They employ a consistent visual value range. They are not organized hierarchically around any particular painting or pattern, but exist as seven independent individuals. The formal simplicity of contracted subject matter—horizontal stripes of blue and white separated by visible pencil markings—calms the viewer. Inside this soothing oasis, shifting relationships begin to appear. Differences between the lines and colored bands begin to emerge and evolve. We begin to ask structural questions: is there a common horizon line across all the works? No. Might there be a mathematical relationship? Perhaps, but it is not readily visible, and according to the artist, if there is one, it’s not intentional. And yet there is a mysterious connection among the works. Together, they seem to create an audible musical harmony (a reference not lost on the artist, whose work was often compared to blank sheet music paper). Each painting is an entity unto itself, and in concert with the other six, it transforms this small space into a monument to infinite perceptual possibilities.

One cannot help but wonder whether they are all the same size. They are; yet each one also claims more space, expanding beyond its slim, silver-toned frame. Together, the seven works literally multiply the possibilities of space, stretching out to surround us with dense vistas that are completely other, yet also familiar. These works are at once dynamic and interactive while maintaining a restful, meditative quality replete with mystery.

The space evokes the interior of Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, with its blue background. Though Martin’s blue is lighter, her paintings without figures, and her room smaller, in both spaces we experience an inexplicable yet palpable transcendence. Here, gesso on a square canvas, pencil lines, and blue and white add up to an infinity of nuances, triggered by protracted looking.

As we observe the paintings, two types of patterns emerge. The first, contained patterns, appear in works like Love, Playing, and Perfect Day. They use a repeated color at the top and the bottom, and the ratios of the internal lines are worked out in relation to these border bands. These patterns are internally structural and self-contained. The second type, repeated patterns, in works like Lovely Life and Friendship, use a two or three-beat pattern that remains resolved inside the canvas, and read like ladders. The Harwood collection includes three contained patterns and four repeated patterns, yet the group is not organized in any predictable tempo. The apparent randomness of the sequence demonstrates a preoccupation not with geometry or mathematical exactitude, but with each painting’s relationship to the whole. As such, the installation is organically articulated and does not adhere to a rigid grid, even as grids are ever present.

Because at no given moment can we see all seven paintings from one point of view, time is also a factor in how we encounter them. The intimate space and large canvases invite us to come forward, move backward, to walk around and to sit. The paintings and the space require movement. And at any distance—one inch, two inches, one foot, two feet away—the variations of the horizontal lines create a harmonious circle, enveloping us.

Upon leaving the Agnes Martin Gallery one senses that even the memory of this visit will remain refreshing and nourishing. How does she do this? Long before there is a painted surface, a certain depth informs Martin’s paintings, allowing them to become a bridge between the daily and the sublime. This link, forged through ordinary living, is evident in all her work, and in her writing.

§

Throughout the centuries, certain works of art have confronted the rigidity of daily life in order to reveal, or attempt to reveal, an essential structure of being. Through this investigation, a pattern or framework is put forth from which a highly charged emotional content can emerge. Though linked to their own times and places, such works are also connected to larger questions of being in the world, questions that are primarily considered philosophical or religious, linked to the language and pursuit of the sublime.

In 1764, Kant wrote: “The sublime moves, the beautiful charms. The sublime must be simple; the beautiful can be adorned and ornamental.” In twentieth-century art, neoplasticism, minimalism, and some forms of abstract expressionism are often seen as materials in search of the sublime. (Interestingly, given her work, Martin did not consider herself to be a minimalist but instead aligned herself with the abstract expressionists.) Nearly two centuries after Kant, the artist Robert Motherwell wrote, “Perhaps…painting becomes sublime when the artist transcends his personal anguish, when he projects in the midst of a shrieking world an expression of living and its end that is silent and ordered.”

According to Agnes Martin, both paintings and contact with nature can prompt a greater awareness of what she calls perfection. Her essential view of the world is of daily life superimposed on top of an underlying perfection. Both paintings and nature, she believes, provide opportunities for a glimpse into another way of being in the world. The work of art links the daily to the sublime; or, in Martin’s terms, by engaging and moving the viewer, art can reveal the basic perfection. According to Martin, perfection is almost like a map, if we pay attention. Once we have received a glimpse of perfection, she believes, we can seek it on our own, and the reaction to perfection is joy.

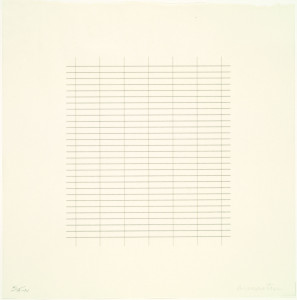

PLATE 11. Agnes Martin. From the series On a Clear Day, 1973. Portfolio of thirty screen prints on Japanese rag paper. 12 x 12 inches each. Yale University Art Gallery. Leonard J. Hanna Fund.

In her lined work and plain grids (even her horizontal compositions should be linked to the grid) Agnes Martin retains emotional purity laid bare, but not naked—a quality particularly evident in series like On a Clear Day [see Plate 11]. Her description of artistic success is self-revelatory and apt: “a work of art is successful when there is a hint of perfection present—at the slightest hint…the work is alive. The life of the work depends on the observer, according to his own awareness of perfection and inspiration.” Martin’s work in all its variations is sublime in the purest sense. (She was well known for destroying works that did not meet this standard, as she saw it.) The repetitions we see in her compositions are always fresh, vivid, and alive, and are part of her own habit of being. Although many artists choose one visual reference and rework it constantly, creating a signature style, it is always important to pay attention to their entire output in order to see each work properly. With Martin’s work, if you have seen one, you have not seen them all. She is like the twentieth-century Italian natura morte artist Giorgio Morandi, whose oeuvre consists of small paintings of a finite group of bottles and shapes. These are gently painted surfaces, and each painting adds a new voice to the entire body of work. The modified (often ever so slightly) and reworked repetition is actually part of the richness of the whole, providing a multitude of possibilities of composition and coloring using the same means.

Since the middle of the twentieth century, the grid has been the premier expression of this aesthetic of the sublime, and Piet Mondrian is its original champion. Progressing from painting the flat landscapes of his native Holland, to geometricized trees and buildings, he came to the grid in deliberate calm and prompted a revolution in understanding how paint on a canvas can contain and advance thought. In a seminal 1979 article, Rosalind Krauss wrote:

In the early part of this century there began to appear, first in France and then in Russia and in Holland, a structure that has remained emblematic of the modernist ambition within the visual arts ever since. Surfacing in pre-War cubist painting and subsequently becoming ever more stringent and manifest, the grid announces, among other things, modern art’s will to silence, its hostility to the literary, to narrative, to discourse…. [G]iven the absolute rift that had opened between the sacred and the secular, the modern artist was obviously faced with the necessity to chose between one mode of expression and the other. The curious testimony offered by the grid is that at this juncture [Mondrian] tried to decide for both.

PLATE 12. Agnes Martin. Islands No. 4, 1961. Oil on canvas. 15 x 15 inches. Yale University Art Gallery. Gift of the Woodward Foundation.

Agnes Martin worked with the grid beginning in the 1960s. Through a series of hand-drawn pencil lines, filled in with delicate layers of color, like Mondrian, she successfully clustered together the most basic and crucial possibilities for the grid as juncture between the sacred and the secular, flattening this polarity (and antagonism) and creating a new way to contain both in harmonious balance. Works like Islands are rigorous, disciplined, and carefully executed: they are exacting yet full of emotional content, deep, varied, and complex [see Plate 12]. Her modest tools—pencil, acrylic paint, and canvas, or watercolor on paper—are all she needs. Indeed, horizontal lines dominate, depicting the point of contact between gravity and grace as an almost inevitable engagement. And with the grid comes symmetry and repeated composition. Through rhythmic harmonies of color and series of patterns, her paintings soar. No color is flat. In organizing her structures of patterns, rhythms, and repetitions, she offers architecture for shaping daily life.

Martin writes: “What was the reaction of the person who first made a symmetrical house? He felt new contentment in the house. He felt a satisfaction in having built it and perhaps an awareness of clarity in his own mind as a means.” Likewise, the late Donald Judd spoke of symmetry in Prints and Works in Editions: A Catalogue Raisonné (1996):

The primacy of symmetry in art and architecture is not very definitive or restrictive because there are so many kinds, some very close to asymmetry, such as some of the numerical progressions that I use. Absolute symmetry is marvelous and it’s also marvelous when symmetry itself allows variation, when the logic of the situation causes or allows an approach to symmetry.

Here we are reminded of the brilliant sixteenth-century architect Andrea Palladio, who turned Roman treatises on symmetry into buildings, architecture which would thoroughly influence generations to come. Symmetry and repetition are linked—and are sources that Agnes Martin draws deeply from both in her paintings and in her building of her three homes.

In Poetics of Space: The Classic Look at How We Experience Intimate Spaces (1958), Gaston Bachelard writes of the house:

….a house is first and foremost a geometric object, one which we are tempted to analyze rationally. Its prime reality is visible and tangible, made of well hewn solids and well fitted framework. It is dominated by straight lines, the plumb-line having marked it with discipline and balance. A geometrical object of this kind ought to resist metaphors that welcome the human body and human soul. But transposition to the human plane takes place immediately when a house is considered as space for cheer and intimacy, space that is supposed to condense and defend intimacy. Independent of all rationality, the dream world beckons.

Some of the greatest thinkers of our times designed homes. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s house in Vienna strangely embodies the uncluttered artistry of his thought. Le Corbusier’s domestic architecture at the Villa Savoye in Poissy also provides a clean space. Mondrian designed houses, as did his Bauhaus colleague, Vordemberge-Gildewart. These select artists demonstrate in their painting an uncanny delight in architectural lines, as they invariably draw on these physical structures in their two-dimensional art. This same phenomena appears throughout Agnes Martin’s oeuvre.

Martin built multiple homes and studios with her own hands, in addition to her painting, printmaking, and writing. Through field research and study of her work, I have come to believe that it was through construction of these rooms for living and creating art that she developed her own mental spaces, which in turn informed the content and structure of her paintings. Indeed, her painting, in subject matter and in its ability to communicate intimacy, is deeply connected to the process of—and the reasons for—building a home.

What does it mean to make your own living spaces? Mircea Eliade, the twentieth-century historian of religions, wrote:

For the moment, consider that to inhabit a territory, that is to say, to build up one’s abode, to build a home, always implies a vital decision which engages the existence of the entire community. To be “situated” in a landscape, to organize it, to inhabit it, are actions which presuppose an existential choice: the choice of the “Universe” that one is prepared to assume by “creating” it.

Even while Agnes Martin chose extreme isolation from others, as during her time in Cuba, New Mexico, we, the viewers of her work, are in fact that “entire community” of which Eliade speaks. I believe the building projects became a way to center her entire “universe,” and that once centered, she could paint again, because what she paints is the core of this center.

In considering Agnes Martin as a house builder, I am reminded of Louise Bourgeois’s depictions of women as house-body. In a series of Bourgeois’s drawings from 1946 to ’47, Woman House, the house replaces the woman’s head, encasing her very identity. The opposite is true of Martin’s houses. Hers are solid shells for living. The builder is not a prisoner of her house. She is free to work, paint, cook, look out her window, sit, and sleep at will.

Martin Heidegger’s 1952 essay “Building, Dwelling, Thinking” offers a critical understanding of the significance of building one’s own house, and can shed light on Martin’s work. He writes: “Dwelling…is the basic character of Being in keeping with which mortals exist…. This they accomplish when they build a dwelling, and think for the sake of dwelling.”

The first sanctuary is domestic space. It is a retreat from the outside; it is safe, warm, and nurturing. In her essay “The Untroubled Mind,” in a discussion of why any given painting is appealing, Martin writes: “This painting I like because you can go there and rest.” Agnes Martin’s houses offer places of dwelling, working, and thinking—and her paintings convey this sense of deep dwelling.

Finally it is, I believe, the metaphor of the room that best holds the multiple dimensions of awe, intimacy, safety, and memory in proportion. The metaphor is made literal in the Harwood Museum’s Agnes Martin Gallery, but it is available in all her work. Of the room, Heidegger writes:

What the word for space, Raum Rum, designates is said by its ancient meaning. Raum means a place cleared and freed from settlement and lodging. A space is something that has been made room for, something that is cleared and freed, namely within a boundary, Greek, peras. A boundary is not that at which something stops, but as the Greeks recognized, the boundary is that from which something begins its presencing. That is why the concept is that of horismos, that is the horizon, the boundary. Space is in essence that for which room has been made, that which is let into its bounds. That for which room is made is always granted and hence is joined, that is gathered by virtue of a location, that is, by which a thing is a bridge. Accordingly, spaces receive their being from locations, and not from “space.”

In the Agnes Martin Gallery, the seven paintings are locations and the gallery is a room, a room in a museum, a sanctuary from daily life. It is a room full of horizons, freeing us through their physical presence to encounter the sublime. It is Agnes Martin’s Taos house and studio, distilled and purified and built in paint.

Martin wrote in one of her journals:

The silence on the floor of my house

Is all the questions and all the answers that have been known in

The world

The sentimental furniture threatens the peace

The reflection of a sunset speaks loudly of days.

Here the sunset, the day at its very end, still stands for day, and the light, the dying light of day speaks on the floor of her house as she reflects in silence. In every moment, the eternal is now, even in the modesty of one’s own home. In order to shape a path, we must live in awareness of the transcendent, in happiness, and seek out encounters with beauty and joy. Only then will we find inspiration on the floor of our house, just as we found it in the Agnes Martin Gallery, a sanctuary, a room, a house where silence lives.

§

This essay is drawn from a lecture for a symposium organized by the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, New Mexico, in March of 2003, celebrating Agnes Martin’s ninetieth birthday. It also takes from research sponsored by the Lannan Foundation in support of a book on Agnes Martin, Making Space for the Sacred, forthcoming from Penumbra Press. The author wishes to thank Linda McKee, chief art librarian and former colleague at the Ringling Museum of Art, for her assistance.