An Ode to Sanctuary

Katie Eleanor (b. 1993) is a photographic artist living and working in London. Using traditional hand-coloring techniques, her practice revolves around illustrating enigmatic narratives that bridge the gap between fantasy and reality. Her work has been featured by the Royal Photographic Society and Yahoo. Her first solo exhibition, The Sialia Marbles, opened at London’s MMX Gallery in November and runs through February 15.

Image: How did this new series start?

Katie Eleanor: The whole project has taken about three years, but the ideas started four years ago. My work is very narrative-based, so I wanted to challenge myself and make a larger collection with multiple stories. The inspiration started with galleries and looking at marble sculptures; I felt an affinity for these objects that seemed almost alive. I loved the way they can capture a story, a fantasy—and the idea of losing these fantasy worlds and stories I have scares me. The statues live for hundreds of years, and they have such an endurance and such as arresting presence about them still.

Image: The title of the series, The Sialia Marbles, sounds like a museum collection. Was this intentional? What does sialia mean?

KE: Sialia means bluebird, who is a kind of alter ego for me. I chose Sialia Marbles to invoke a sense of a sculpture court at a museum or maybe the Vatican. It is meant to be slightly subversive: while older collections like the Elgin Marbles and the Townsley Marbles were named after wealthy white men and consisted of classical subjects, these marbles are universal and fantastical, unbound by history, gender, or species.

In his 1947 essay “Le Musée Imaginaire,” André Malraux dreamed of a museum that could fit into an album, and photography brings this idea to life. I am drawn to this idea of everybody carrying around a unique collection of images and memories which form a personal, subjective take on art history. The Sialia Marbles are kind of like a wing of my museum.

Image: What’s so interesting about these works then is that despite your attraction to the unchanging nature of statues, you haven’t used sculptures in your works. Instead you’ve used people. Could you explain the decision to use human subjects rather than creating or finding sculptures? People are surely the most ephemeral material.

KE: There are a couple of reasons behind that. It started out of necessity, of not having access to materials and spaces. I’m not a sculptor, but I wanted to construct my own stories. Photographers have often used sculpture in order to challenge our idea of a “sculptural” body or object, by casting them in a two-dimensional light. I love playing with perception. A lot of my work is influenced by the nineteenth century—the pictorialist movement for instance. When photography was a new experiment, people would play around with perception tricks—Victorian paper theaters or even the Cottingley Fairies hoax, for example, where angles and sets are integral to the viewer’s experience.

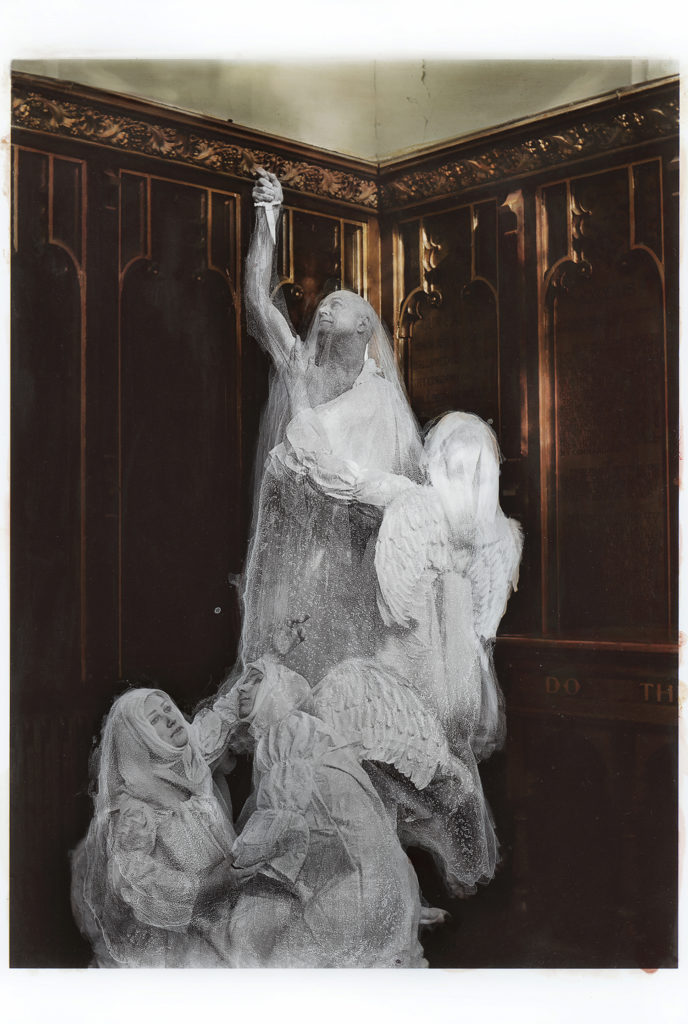

An Ode to Sanctuary

Image: Have you delved a lot into this history of the interaction between sculpture and photography? In a lot of ways they seem opposite art forms, but you’ve managed to combine them. Could you talk us through your process?

KE: I have studied works by early photographers such as Oscar Gustav Rejlander (1813-75), whose tableaux tend to be very sculptural. I’ve slept next to a copy of his Allegorical Study (Sacred and Profound Love) from 1860 for years. Photography and sculpture have such a loaded history together. Back then, statues were an easy thing to photograph, as they kept still through the long exposure times. They were patient and willing subjects! When photography started to be consumed via devices such as stereoscopes, sculptures were often a popular subject. These original objects which only a select few people had access to became consumable and could be “transported” to people’s homes.

My sculptures are more like performance art or land art. They are ephemeral, yet they survive in the photograph. The characters were performed by the people I worked with and were planned out very much in advance. The narratives are fragmentary and fleeting, much as they are in my imagination. I have to grasp these stories with my nails to stop them disappearing.

Image: What is creative process of making one of your images?

KE: I come up with the concept and create a set to shoot in. Then I paint the performers and dress them up. Most of my shoots are done in my living room and are very low-tech despite the kind of grandeur I try to convey in them. I think that links back to what we said about playing with perception.

Image: Seeing the prints in person, it seems like the shoot and the photographs themselves are just the beginning of a whole process?

KE: Yes. My aim with my photographs is to create works that are original and tactile, like sculptures. The images are one-off hand-colored prints. They are black and white before I add color and texture to the surface in post-production.

Image: There is such an ambiguity in the work between what is real and what is not.

KE: With pieces such as Waking/A Bridge, the shoot took place in a parking lot behind my house. The ivy and foliage are real, but the purple colors are painted on and pure fantasy.

Walking a Bridge

Image: What is the advantage of doing all the post-production work by hand rather than digitally?

KE: For me it’s all about tactility. I like to get my hands all over it. Leaving traces—finger prints, textures, even my hair—makes me feel that the works are coming straight from me, from my body, rather than there being a barrier between myself and the work.

Image: One noticeable theme in the series is religious iconography and settings, particularly in Saint Lucy, An Ode to Sanctuary, and A Chorus/Armour. Could you explain the thinking behind this?

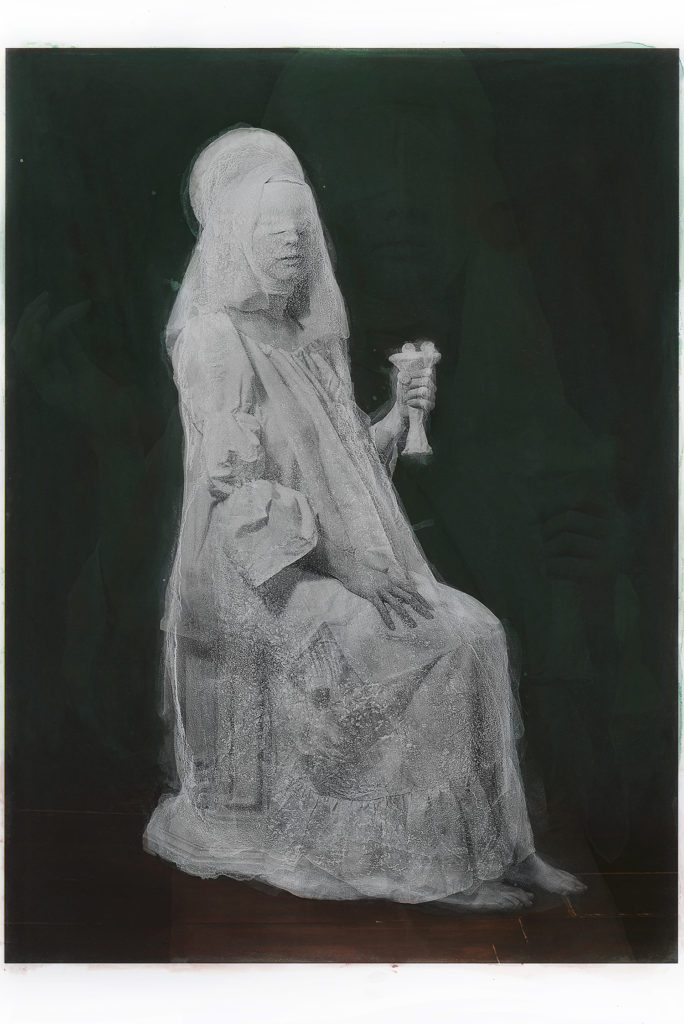

KE: This series has been the first time I have felt comfortable using recognizable iconography like saints or myths such as Daphne along with my own creations to create an anthology of ideas. Saint Lucy is a good example. I visited the National Gallery and saw a painting of her by Francesco Del Cossa (1470). I hadn’t heard of Lucy before, but I was struck by the contrast between the brutality of her story and this ornate, delicate, almost whimsical rendering. In my version, the bandages over her eyes are significant, as I find the eyes of sculptures particularly haunting and vacant. This piece is a kind of homage to an amazing character in history.

St. Lucy

Image: Your group shots feature angel-like creatures inhabiting church settings. Where did the inspiration for these shoots come from?

KE: I love tableaux vivants and creating intense, ambiguous scenarios with my performers. Angels are found in so much religious and historical visual culture, so they are familiar. They also symbolize protection, particularly when the series is viewed as a whole. I am not a particularly religious person, but I believe in sanctuary. My brain and my imagination are my sanctuary, and that is something I associate with these solemn spaces. It’s all creating a sanctuary for the viewer to inhabit, a sense of stillness and introspection.

Image: What kind of experience are you hoping to create in your exhibition at MMX?

KE: A feeling of numinousness. That feeling of smallness and the uncanny you can get in religious spaces especially. A sense of being surrounded by figures but completely alone. The emotions conveyed by the groups drive the narrative. I was drawn to the contrast between serenity and desperation. I wanted to play with how bodies can interlock and become monumental.

Image: Obviously working with real people helps you avoid the technical limitations you might find with other art forms, but what were the challenges of this?

KE: Well, I quickly found that bodies don’t always bend in the way I imagined! Some of my subjects were friends, but I have also worked with many performance artists, life models, and dancers to achieve a particular pose or creature. I have no aesthetic expectations with my subjects; I look for dedication to a character. A lot of contemporary photography focuses on the humanity and personality of the subject, but I seem to strip it away.

Daphne

Image: Like Medusa. You turn your subjects into stone.

KE: It is very unlikely that my subjects will be themselves in my work, which makes me feel a bit cruel. But watching people inhabit my creations is so important to the process.

Image: How do your images function? Are they aesthetic objects or devotional objects, or both?

KE: They are devotional in a sense, almost for the sake of the experience, the emotion, the sensuality—an homage to creativity and the sanctuary I find in it.

Follow Eleanor on Instagram at @_katieeleanor.

Image depends on its subscribers and supporters. Join the conversation and make a contribution today.

+ Click here to make a donation.

+ Click here to subscribe to Image.

The Image archive is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Written by: Maryanne Saunders

Maryanne Saunders is a PhD researcher at King's College London focusing on gender, sexuality, and language in contemporary religious art. Her work has appeared in Times Higher Education, The Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception and the edited volume Encounters: The Art of Interfaith Dialogue. Follow her on Twitter @maryanne_fs