In this regular feature, contemporary artists from around the world describe their art practice, spirituality, and current work.

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, LAHORE was a diverse literary and artistic community of people activelyengaged with their city’s culture. My birthday cakes were ordered from the Zoroastrian neighbor down the street, and I studied in a convent school under Irish and Anglo-Indian nuns, who eventually moved or passed away, leaving no trace. With the Afghan war in the 1980s and then the “War on Terror” of the 2000s, this diversity faded, and we became a monolithic culture with sharp boundaries. Anyone with a college degree and a little bit of money applied for immigration to North America, leading to a mass exodus of brilliant Pakistanis.

Of those who remained, many willingly transformed. My grandmothers’ beliefs were internal and private. Wearing the burka in public had become a thing of the past, from before the Partition of Pakistan from India in 1947. Now, on the bus, I see young students in blinged-out burkas, fake Swarovski crystals glittering on their sleeves and around their shrouded heads. As more Pakistanis move to the Gulf States for work, they bring back ideas of “pure” or “unadulterated” Islam and “authentic” dress codes which are foreign to this country. Even our Urdu language, which draws largely from Persian, has added more unfamiliar Arabic-based words.

Saba Khan. Monument or an Undecided Event, 2019. Enamel on fiberboard. 60 x 60 inches.

Local religious traditions are also fading. My ancestors are mostly Sufi saints, but my family has stopped holding its annual death anniversary, in which soulful qawwali singers would perform all day. With increasing affluence, especially among the aspirational middle class, a narrow conception of piety has become a sign of upward mobility. Majestic houses in the new town bear large stainless-steel Quranic inscriptions on high walls built to ward off envious eyes. On television, Islamic game shows generate millions of dollars, including one with a host who has condemned minorities, leading to an upsurge of violence. This dramatic cultural and political shift—familiar across South Asia—has squeezed out any public hint of freedom of expression.

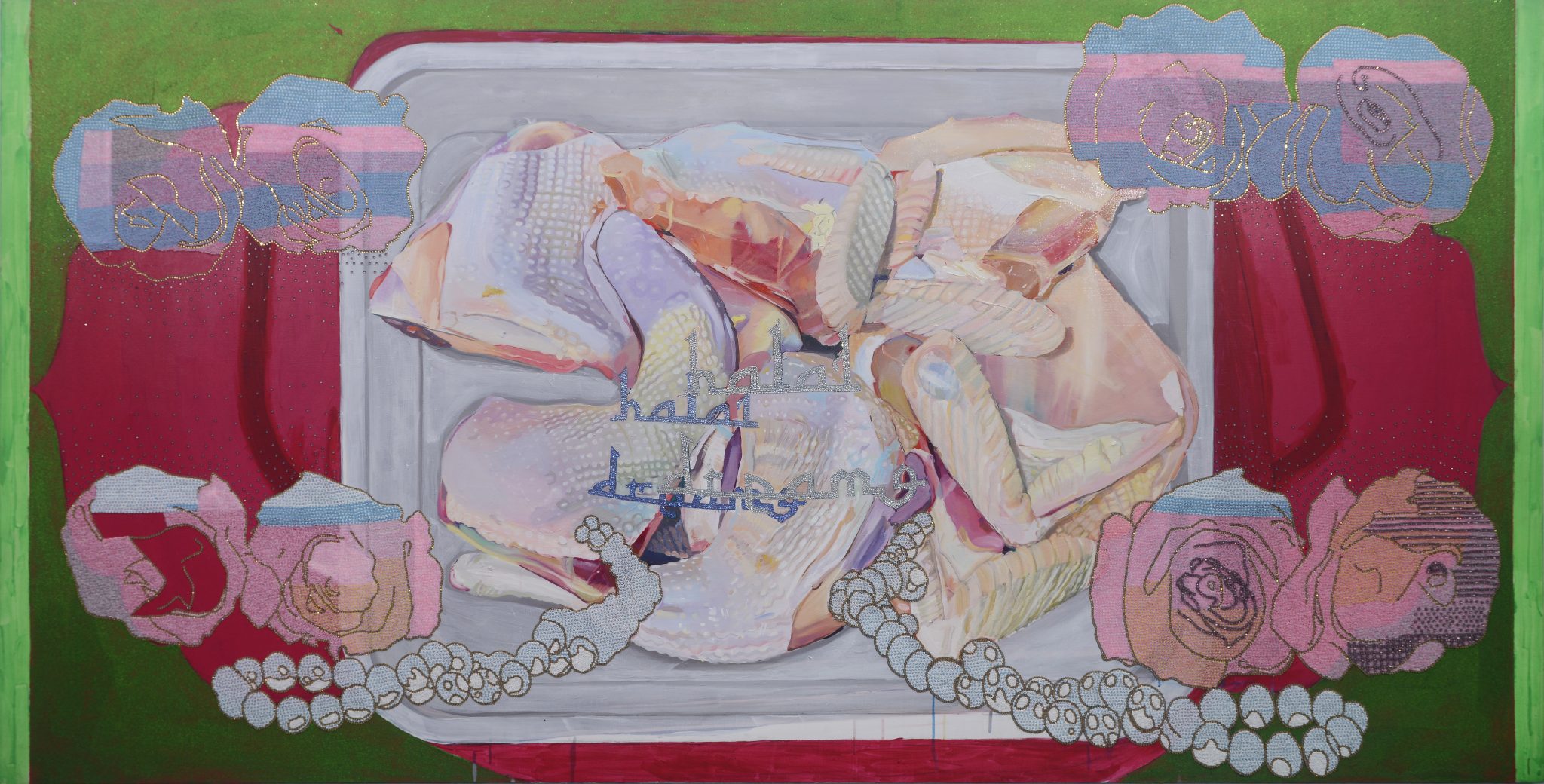

In this constricted, iconoclastic environment, people look for loopholes to express themselves visually and aesthetically. I am interested in these gestures, not only found in displays of public piety but also in the bazaar. I am drawn to objects made for religious celebrations and home décor, which adapt influences from various parts of the world, from the Gulf States to Bollywood and China, creating an amalgamation of local religious kitsch.

Saba Khan. Halal Dream, 2017. Oil, acrylic, beds, and crystals on canvas. 48 x 96 inches.

While I am interested in kitsch and popular culture, there is still a danger in making art works appear reductive, saccharine, or decorative. There is a fine line between taking inspiration from the vernacular and falling into the trap of mimicking it without a rigorous discourse. That is what I see in many officially commissioned public projects, from purpose-built buildings to green-belt “beautifications”—vanity projects that reflect popular tastes and are constructed from cheap, ephemeral materials. What I enjoy instead are the faults of the hand, the jagged edges, the brashness of jugaar (an Urdu word meaning to innovate within a very small budget). This gave me the impetus to move my work from the studio to the bazaar, where small shops became collaborators and extensions of my studio. In doing so, I challenge not only what “counts” as beauty in Pakistan today but also western canons of beauty and what is defined as fine art.

Saba Khan is a visual artist and a curator. Founder of the Murree Museum Artist Residency, she has received grants from the Foundation for the Arts Initiative and Fulbright Foundation. Her work has appeared in the New York Times as well as in The Eye Still Seeks: Pakistani Contemporary Art (Penguin Studio).