Remembering India’s Partition

A Preamble

IWAS BORN IN LAHORE, forty years after the partitioning of India in 1947, which resulted in the creation of Pakistan. India had been more or less under British dominion since the 1750s, but as the twentieth century neared its midpoint, World War II massively depleted the Empire’s resources. That, combined with persistent anti-colonial resistance, led Britain to accede to demands for Indian independence. The Indian independence movement was led by two primary political parties, the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress. The British decided that the subcontinent would be divided into two states: the Muslim majority state of Pakistan and the Hindu majority state of India. Cyril Radcliffe was appointed to mastermind this division.

Radcliffe was a British lawyer who had never been to India prior to his appointment as chief cartographer for the daunting project. He infamously spent about a month and a half (from July 8 to August 17, 1947) poring over outdated maps and censuses of the region before producing a border, thereafter known as the Radcliffe Line. This line bisected the provinces of Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east to fashion a new homeland for India’s Muslims called Pakistan. In the months that followed, approximately twelve million people crossed the border in both directions: Muslims moving from India to Pakistan and Hindus and Sikhs from the newly demarcated Pakistan to India.

The Partition of 1947, with a capital P—such is its symbolic and literal enormity for South Asians—was hastily and irresponsibly done. In the wake of the passing of the Indian Independence Bill by the British Parliament in July 1947, not one committee was formed to address the imminent mass displacement. Amid the confusion and chaos of new borders, forced crossings, and growing tensions among Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus, violence erupted between communities that had hitherto lived and worked together. Around two million people were killed. Between seventy thousand and one hundred thousand women were raped. Caravans of refugees attacked and mauled one another as they crossed the Radcliffe Line. Villages were burned to the ground. Women abducted from their families were forcefully converted to their abductors’ religions. Historians including William Dalrymple and Ayesha Jalal have drawn comparisons between the bloodbath following the partitioning of India and the Holocaust.

Then, less than a generation later, in 1971, another rupture took place when Pakistan’s eastern wing seceded to become Bangladesh. East Pakistan, which had a Bengali-Muslim majority, was separated from the western region by a thousand miles of Indian territory, but also by a different language and culture. The breach between the two wings widened over the years as West Pakistan suppressed its eastern province culturally and politically. In 1970, West Pakistan’s military junta dismissed the landmark victory of the Awami League (an East Pakistan-based political party) in the country’s first federal election and, to quash growing Bengali discontent, launched a Bengali genocide in East Pakistan. In the civil war that ensued, three million people were killed and around ten million displaced. West Pakistan’s military forces were also responsible for the rape of two hundred thousand to four hundred thousand Bengali women. In December 1971, with the surrender of West Pakistan, Bangladesh was formed.

In just twenty-four years, three countries emerged out of one through what seemed to be the severing of centuries of intricate ties. But it is obvious, if one looks at the subsequent histories of all three of these countries, that a well-woven tapestry cannot be picked apart so easily.

Growing up, my only palpable link to the cataclysmic Partition of 1947 was personal: the stories of my maternal great-aunt. My sisters and I called her Nanto, an amalgamation of the Urdu endearment for maternal grandmother, “Nano,” and the English “Aunt.” She was an inveterate raconteur, with an impressive repository of stories that she had gathered from her own elders and from her travels around newly formed Pakistan.

Nanto had been a professor of philosophy in the government’s employ, stationed during her tenure in various towns and cities of Pakistan. In Lahore, where she taught for the last decade before her retirement, she collected old editions of European fairytales and translations of Russian folktales, salvaging them from roadside bookstalls.

Nanto never ran out of stories. She would tell us stories of prophets in the desert, how people tried to scheme against them, how they were always too clever for the tricks or were helped by God in some magnificent manner. These prophets walked away wise and white-haired from infernos and deluges in which screaming populations burned or drowned. She would tell us stories of princesses who set up elaborate challenges to find men smart and sensible enough to marry. She would tell us stories of sisters who were whisked away by magic men and beasts into the night, taken from their secure and guarded rooms to the limitless wonders of the outside world.

Nanto (Qaisera Sultana Zaidi). Photo from the author’s personal archive.

Lurking among the teeming archives of stories in Nanto’s remarkable memory were the Partition stories—concise and bloodcurdling accounts of what transpired when she, at just ten years old, made her way with her parents and three younger siblings from Karnal, India, to Lahore, Pakistan. The Partition stories took place sometime between September and October, 1947.

I wonder if it is even right to call them stories. They had none of the mix-and-match, ad hoc quality of her other stories (which could be part Arabian Nights, part Quranic narratives). They had no hope, no comic relief, no subplots, no quibbling, no light-hearted verses interwoven into the fabric of the central tale. They had no preambles. They just began…

“That night, our gatekeeper came running, screaming as he did at my father, ‘Zaidi sahib, they’re coming! They’re coming! Get the begum and children out!’ On hearing this, my father gathered all of us in the little room next to the kitchen, which had a door leading to the backyard, and he told our mother that we had to leave immediately for Pakistan. And then we ran. We ran out of our house into the night, taking (or so we all thought at the time) nothing but the clothes on our backs…”

She would go on to recount some of the horrors they witnessed as they made their long, torturous way to Lahore by train, narrowly avoiding death. Not everyone was so lucky; many trains crossed the border with entire carriages of butchered bodies. One of the stories that is seared into my memory is of a young mother on the train who carried the corpse of her murdered baby. She was so distraught by her loss that, when the train crossed a river and some passengers prompted her to dispose of the body, she threw her living infant into the water by mistake.

As children, we were content to listen to Nanto without ever asking her why she thought this or that happened. We accepted these stories without preambles or explanations. As teenagers, we passed through an educational system that gave us a one-sided explanation: THE MUSLIMS OF INDIA WERE OPPRESSED BY THE HINDUS AND NEEDED A HOMELAND OF THEIR OWN AND SO, AMIDST THE GREAT SACRIFICE, PAKISTAN WAS BORN. Then, as grownups, we slipped into independent research outside of the classroom, where in Pakistan the presence of the state invariably hovers. This research led to the discovery of a preamble that, though more credible because of its complexity, turned out to be as unsatisfying as the one offered by our textbooks. For it gives us no real answers either, and no closure, about the horrors we heard of in our Nanto’s stories.

What did lead up to the carnage of that autumn? Why did neighbor turn against neighbor, compatriot against compatriot? Why did the forging of a border unleash such hate and violence?

The gradual polarization of communities on religious grounds by the British played a crucial role, writes historian Alex Von Tunzelmann. In the years leading up to independence, the British policy of “Divide and Rule” aligned neatly with the personal ambitions of Indian politicians and the sectarianism promulgated by Indian political parties.

But even this explanation does not seem complete. The scale of human suffering unleashed by the Partition was simply unprecedented and continues to haunt generations of Pakistanis and Indians. The governments of both countries have not properly addressed this; instead, each side has widened the lacunae in the narrative surrounding the Partition, making it easier to vilify the other country. Up until the opening of the Partition Museum in Amritsar, India, in 2017, neither country had even a single memorial to the devastation.

The human cost of Partition remains officially unacknowledged, cloaked beneath nationalist displays. At the India-Pakistan border at Wagah, Punjab, border guards symbolically recall the bellicosity between the two countries every day in an evening ritual. On both sides of the border, sentinels march, stomp, and lunge towards each other in an absurdly choreographed showdown before they lower their respective flags and close the border gates.

In the seventy-two years since the Partition, it has largely been through art and literature—outside the boundaries of official political discourse—that Indians and Pakistanis have grappled with what took place and come to a semblance of closure. In that artwork, I find many of the themes of Nanto’s stories playing out—themes that have allowed these artists to move through the anguish of the Partition and toward a resolution. Nanto’s imagination was forever interlacing preludes and quests and denouements from different stories. In doing so, her stories came to reflect the collective memory of India itself.

Like Nanto’s stories, this artwork is vividly syncretistic, which makes it a fitting metaphor for the region it comes from—a colorful, bristling, stinging, overpowering mélange of cultures, religions, languages, and memories. This art tells the story of the people of India and Pakistan. In the absence of any kind of monuments to the Partition, it is the people’s stories, after all, that serve as a site of convergence, remembrance, and the possibility of peace

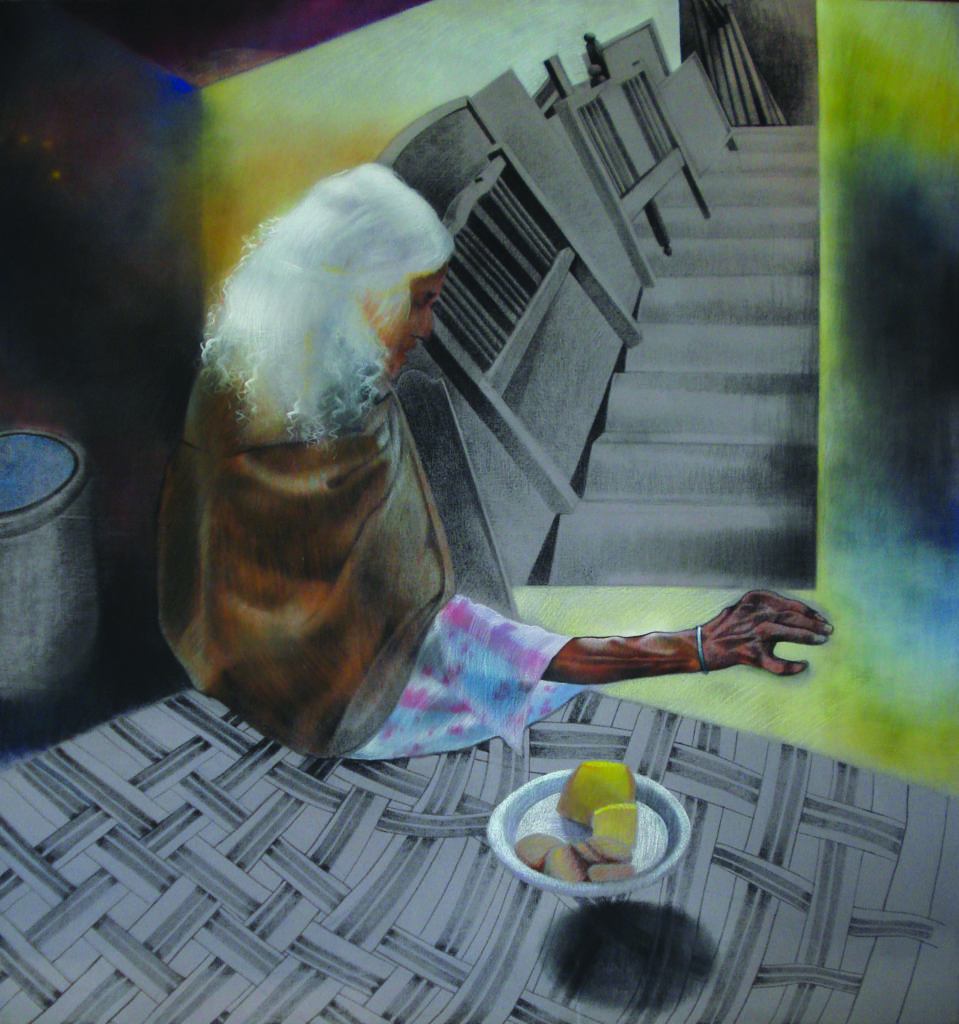

Dua Abbas Rizvi. Nanto the Storyteller, 2009. Pastel on canvas. 66 x 60 inches.

Maps and Miscalculations

Nanto was a Shia-Muslim, Urdu-speaking, Indian-born Pakistani. Because of her hyphenated identity, her loyalties were manifold. And in order to structure them into coherent narratives that would lay to rest the doubts that always shadow loyalties, she altered maps to accommodate the demands of her stories.

Maps in Nanto’s stories were fluid and shifting, their borders negotiable. Characters could be carried over and across them by peris, fairy-like beings from Persian myth, or could traverse them as they slept, waking up in strange terrains. Sometimes, the distance between the Arab and Indian peninsulas expanded to underscore the trials of a Sayyid ancestor fleeing Umayyad persecution in the Middle East, which historian Andreas Rieck writes about in his book The Shias of Pakistan: An Assertive and Beleaguered Minority.

At other times in Nanto’s stories, distances shrank at a whim, as when she told us about the shrine of Bibi Pak Daman (“The Chaste Lady”) in Lahore, how it marked the spot where one of Imam Ali’s daughters was protected by the earth itself as she fled a group of nonbelievers with dark designs. Bibi Pak Daman prayed to God to save her, whereupon she was swallowed by the earth. At this juncture, Nanto appended the finale of the Apollo-Daphne myth to her own story: only the Chaste Lady’s long braid remained above ground, transformed into a luxuriantly knotted tree that can still be seen at the shrine today.

In stark contrast to these fluid geographies stood the Radcliffe Line—an obdurate border that Nanto herself crossed once and never crossed again.

Indian and Pakistani artists have frequently recognized the unique role of the Radcliffe Line in the region’s history through their art. Among the artists who have approached the Radcliffe Line through their work is the Indian-born American Zarina Hashmi. Zarina, who prefers to use her first name only, has a hefty oeuvre marked by her enduring fascination with mathematics, architecture, printmaking, and paper. Her minimalist works explore ideas of home, belonging, and displacement—themes that have particular resonance for the artist, who (like Nanto) was ten years old at the time of Partition. Zarina’s family moved to Pakistan in 1959, but she remained in India and then traveled to Japan, Germany, France, and Thailand with her diplomat husband before settling in New York in 1976. After all these years, she has not been able to relinquish memories of her ancestral home in India.

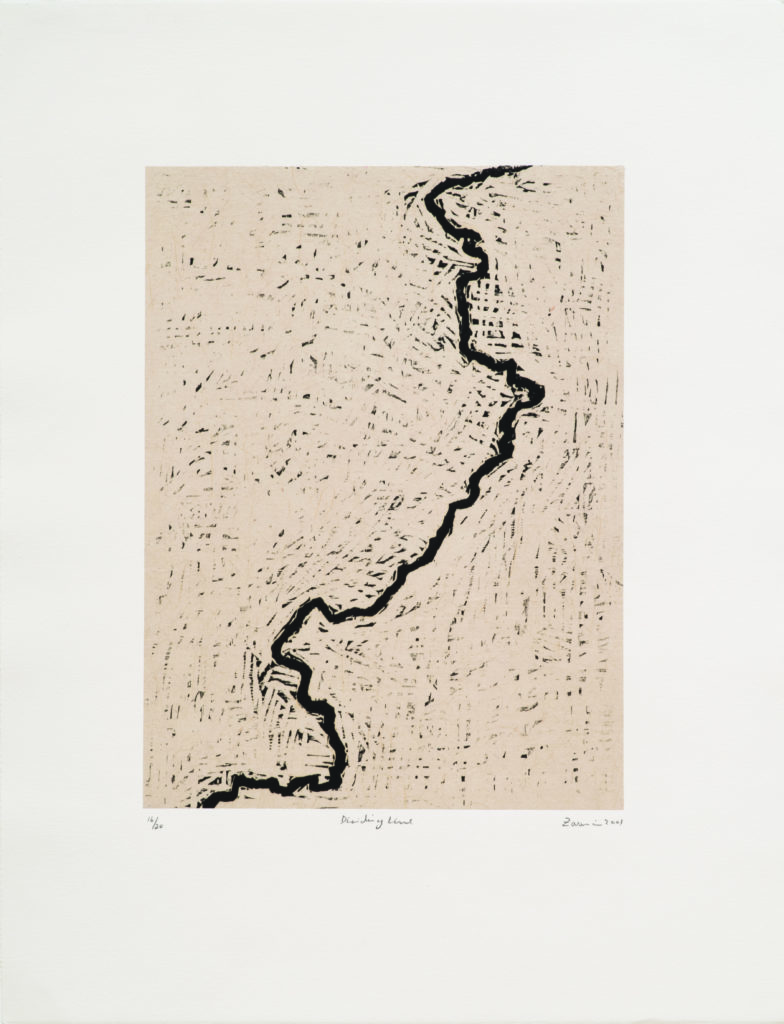

Zarina’s prints reflect the significance of the Partition to her own history. They feature frequent references to maps and crossings, often coupled with words in Urdu (her mother tongue). She has visited the Radcliffe Line in eloquent yet resolutely simple works such as Atlas of My World IV and Dividing Line (both 2001) and the more recent Abyss (2013).

Atlas of My World IV superimposes an enlarged Radcliffe Line onto a densely outlined map of Pakistan and India. Magnified and reiterated, the border convulses over the two countries, appearing as “a twisted umbilical cord both separating and connecting these two supposedly distinct nations,” as Aamir Mufti writes in the essay “Zarina Hashmi and the Arts of Dispossession.”

On the other hand, in Dividing Line and Abyss, Zarina removes all indications of territory to present the border as unmoored and almost abstract—in the former as a thick, unruly line in black and in the latter as a neatly hatched, riverine one in white. Through these works, Zarina evokes both the finality and futility of the India-Pakistan border—a line that shaped the history of the region but, until it was attributed meaning by the imagination of officialdom, was essentially meaningless. By taking away the minutiae that make a line a border, Zarina forces us to rethink geographical boundaries, their arbitrariness, and the abridgment they cause of lives, cultures, and history.

Zarina. Dividing Line, 2001. Woodcut on Indian handmade paper mounted on Arches Cover white paper. 25½ x 19½ inches. Courtesy of the artist. www.zarina.work.

Friendly Interventions

Among my favorite of Nanto’s tales were her comical accounts of mistaken identities and switcheroos masterminded by impish jinn and peris. In one such story, two jinn switch a kind, tidy, and considerate woman with her ill-tempered, slovenly, and selfish neighbor to teach her unappreciative husband a lesson. In another, a hardworking and conscientious farmhand is avenged by his crafty and irreverent twin brother, who trades places with him to teach his cruel master a lesson. Nanto would act out the ensuing uproarious misunderstandings and we would laugh and laugh, applauding the mischievous interventions.

In 2000, a group of artists from Pakistan swapped work with a group of artists from India in an intervention that was at once mischievous and poignant. Each group unobtrusively installed the other’s pieces in public places like roadside cafes, tea stalls, and betel kiosks throughout Karachi and Mumbai. The hope was to restore a lost link between the twin ports that used to work together at the heart of India’s trade and commerce during the Raj.

Modern, cosmopolitan, and built on the industriousness of an astonishing array of communities (including Jews, Parsis, Christians, Hindus, Bohras, Banias, and Khojas), Mumbai and Karachi were alike in many ways. Businessmen, tradesmen, and a cultural elite moved easily between the two. But the Partition transformed the easily traveled distance between them—some 475 nautical miles—into an insurmountable one. Decades of political tension between India and Pakistan cemented the impassibility between the two cities.

The art exchange project was called Aar Paar (Urdu for “across”), and it was coordinated by Pakistani artist Huma Mulji and Indian artist Shilpa Gupta. Through Aar Paar, artists of both countries sought to circumvent the bureaucracy embedded in the India-Pakistan border and, at least symbolically, allow a bridging over, an embrace, a rekindling of memories of Mumbai in Karachi and of Karachi in Mumbai.

The project had a second iteration in 2002, which tackled the political fallout between the two countries more purposefully. Participating artists (greater in number than before) traded monochromatic works via email, to be printed locally in Mumbai and Karachi and proliferated in both cities as posters and flyers. Compared to the first instance, which was inherently an exchange, this was an infiltration. In the wake of a terrorist attack on the Indian Parliament and a military standoff between India and Pakistan in 2001, it became imperative for artists to evoke shared histories, overlaps of languages, and common cultural interests of the citizens of both countries through publicly disseminated art. The contributions for Aar Paar (2002) included posters referencing Bollywood films (enjoyed massively on both sides of the border), a joint culinary heritage (a map of Karachi showing the city’s many eateries named after Indian cities), and the popular design vocabulary of both countries.

Like the switcheroos and interventions in Nanto’s stories, Aar Paar was at once subversive and edifying. It was as much about teaching the authorities in both countries a lesson as it was about proving the persistence of familial ties.

The Magic Bundle

Magic purses and sacks recurred in Nanto’s stories—a legacy, most likely, of tales from Tilism-e-Hoshruba, an Urdu fantasy written by Syed Muhammad Husain Jah and Ahmed Husain Qamar in Lucknow, India, in the 1800s. Tilism-e-Hoshruba was derived from Dastan-e-Amir Hamza (The Adventures of Amir Hamza), the Persian epic inspired by Hamza, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad famed for his bravery and military skills. Tilism-e-Hoshruba featured Hamza, his sons and grandsons, and his loyal trickster friend Umro (or Amar) Ayyar. Umro Ayyar had in his possession the zambeel, a magic bag of tricks that allowed him to vanquish fearsome foes and get out of difficult situations. Nanto was very fond of the zambeel and worked it into many of her stories as a deus ex machina.

I am reminded of the zambeel when I come across Margaret Bourke-White’s chilling Partition photographs that show migrants crossing over to their new homelands with only those belongings they could carry on their heads or on sticks propped up on their shoulders. The unceremonious sacks and bundles—remains of settled lives and intact families—are powerful symbols of the tragedy of the migrant.

Salman Toor. Upside Down Party, 2019. Ceiling mural, oil on canvas. Courtesy of COMO (Contemporary/Modern) Museum of Art, Lahore.

In the work of Pakistani artist Salman Toor, these sacks and bundles become part of a vocabulary of cultural dislocation that the artist has developed in recent years. Toor, who works between Lahore and New York, is known for his narrative paintings of supple, languishing, mostly South Asian characters who while away the hours in dim cubby-hole apartments or intimate parties. They exude a millennial ennui, but also something atavistically sadder: the sadness of never truly belonging, of living between cultures, social strata, and stereotypes. The characters are the flotsam of a region caught between decolonization and globalization, and so they dance to Whitney Houston and listen to classical Indian ghazals and consort sometimes with white acquaintances and sometimes with the ghosts of their ancestors.

In Upside Down Party (2019), Toor deploys his favored visual device of the party to encapsulate the vertigo of displacement. Upside Down Party is a permanent painting commissioned by the COMO (Contemporary/Modern) Museum of Art in Lahore for its circular ceiling. Assorted characters whirl in a confusion of arms and dislodged objects. The painting contains several tropes representative of the artist’s inventive iconography: the servant, the migrant with his bundle, the partying socialite, and the desaturated individual who may be a ghost or a memory, or both. Though apparently randomly thrown together, the figures, in groups of two and three, eerily enact the machinations of empire and its enduring effects on the once-colonized. Important figures from Pakistan’s political history rub shoulders with anglicized counterparts, while members of a distinctly South Asian working class edge around them with trays. Navigating this mass of gesticulating bodies is a migrant, his bundle sticking out of the party’s heat like a small, sad flag for generations wronged by history. The migrant’s bundle is disruptive—it pins the party to a context but also brings to it the promise of centrifugal movement. Here, as in other works by Toor, it is suggestive of the loss of an identity and a home but also of mobility, new beginnings, and escape from stringent cultural definitions. It becomes, in a sense, the zambeel.

When Nanto and her parents and siblings finally arrived in Lahore in 1947, they put up in a refugee camp before eventually moving to Sahiwal, a city about a hundred miles from Lahore. There they started a new life.

On reaching the safety of the camp, Nanto’s younger brother—my grandfather—beckoned to her to see something that he had managed to bring from their house in Karnal. Curious and a little afraid, Nanto peered into a small bundle. Inside was an ornate black wooden box, and inside the box were numerous compartments. Inside the compartments (some of which opened again to reveal secret compartments) were thick wads of notes—her brother’s eidi (a gift of money given to children on the festivals of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha), which he had been saving for the past three years.

“How did you manage to bring this with you?” Nanto asked, incredulous.

“When Abba told us we were leaving, I rushed to the cupboard under the stairs and pulled this out from underneath all the other bags and quilts and rubbish in there. I didn’t want to leave it. I’ll give it to Abba, maybe we can buy a new house with it,” my grandfather said, his eyes twinkling at the splendid trick he had pulled—the marvelous secret of his zambeel.

Nanto passed away in 2012, sixty-five years after the Partition. By that time, I had been flirting with philosophical texts just long enough to wonder how Nanto reconciled her daytime philosophical pedagogy with her nighttime fabulism. But now, the more I think about her life, with its dangerous crossings, acts of quickness and cunning, and magic sacks and bundles, the more I begin to understand why she put such store in these themes, and why it was she returned again and again to these stories: It was through them that the terrified, homeless girl inside her tried perennially to navigate loss and change to arrive at hope and possibility.

Exterior of wooden box containing eidi that the author’s grandfather smuggled from Karnal.

Interior of wooden box containing eidi that the author’s grandfather smuggled from Karnal.

Dua Abbas Rizvi is a visual artist and art journalist based in Lahore and a member of Image’s editorial advisory board. Her artwork has been part of exhibitions at home and abroad, including Stations of the Cross (NYC) and Art for Education: Contemporary Artists from Pakistan (Milan).