Tobaron Waxman is a Canadian artist, curator, performer, singer and archivist currently traveling around Eastern Europe. Waxman is transgender and a former Orthodox Jew–identities that would seem to be in conflict when one considers the immutable gender binary that shapes the lives, experiences and actions of most practicing Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities. Waxman’s work focuses on these key themes within religion, gender, politics, and identity, using religious and cultural motifs as more than simple critiques of dogma; instead, they “audaciously invest centuries-old texts and rituals with new relevance and insight.”

Today, Good Letters contributor Maryanne Saunders introduces and explores key pieces from Waxman’s ouvre, reflecting on how these works speak to the relationship between faith and non-conformity to traditional religious or cultural standards.

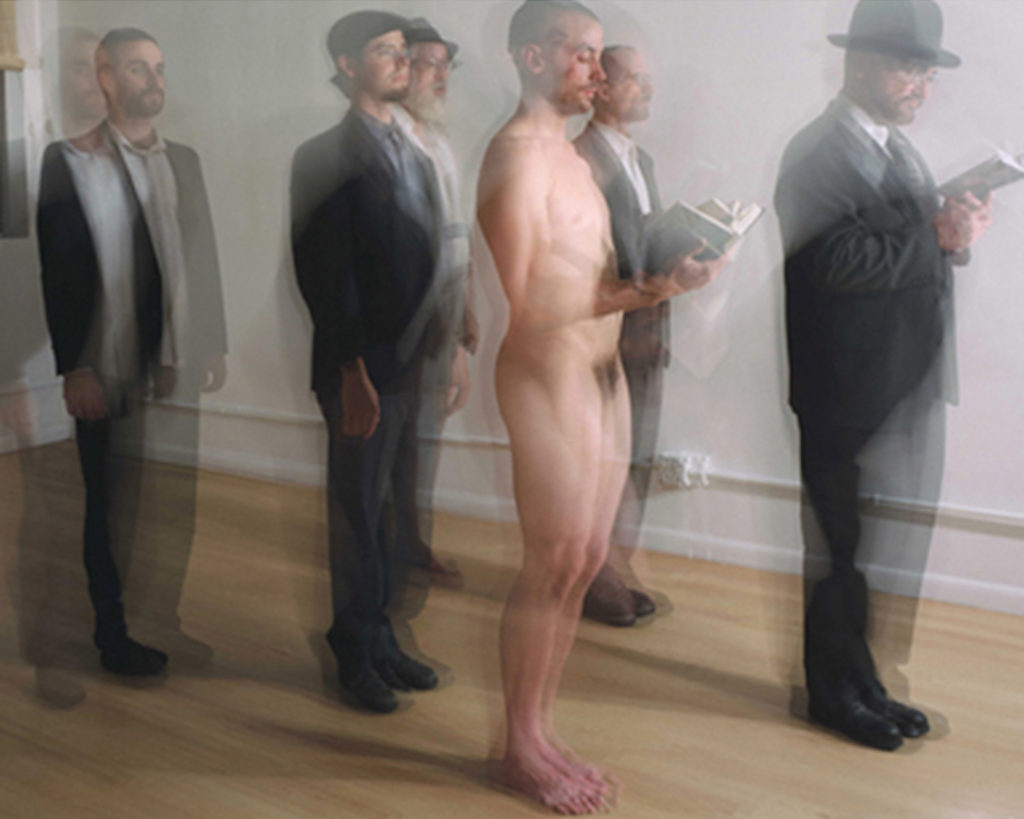

The first work we’ll look at is the Amidah Triptych from 2006. The triptych is made up of three photographic panels each referring to one of the three times of day when the central Jewish prayer–the Amidah, which means “standing,” is recited. Rather than a minyan, or group of 10 men, in each photo, the artist places six figures in each image, for a total of eighteen figures in the composition, representing the eighteen steps of the prayer. All of the blurred figures are praying and shockelling, or rocking back and forth, but one of the figures is both entirely nude, and depending on which image we focus on, evidently trans.

Waxman said in an interview that they make “work which takes our gender binary and reframes it in a manner which is both literate to traditional sources and astute in terms of a transgendered informed reality.” They are “concerned specifically with embodiment, and the juxtaposition of my own body in that shared context with the bodies of the other men who were around me all the time.”

Those images, although made over a decade ago, appear to explicitly address controversies surrounding trans-rights that persist to this day, including where trans and gender non-conforming people fit into gender segregated spaces such as public toilets, and transpose them into their religious context, where trans Jews can find themselves fighting involuntary battles over where they sit in a gender-segregated synagogue.

Waxman’s inclusion of a trans man in a group, praying alongside other men firmly places them on the “male” side of the binary, for which they feel both longing and contempt. But the model’s nudity adds a sense of the vulnerability of the figure’s position and the scrutiny faced from the community. The lack of reaction from their counterparts in these images may suggest to the beholder that this nakedness and exposure is internalized in the figure–something they feel, rather than something they are.

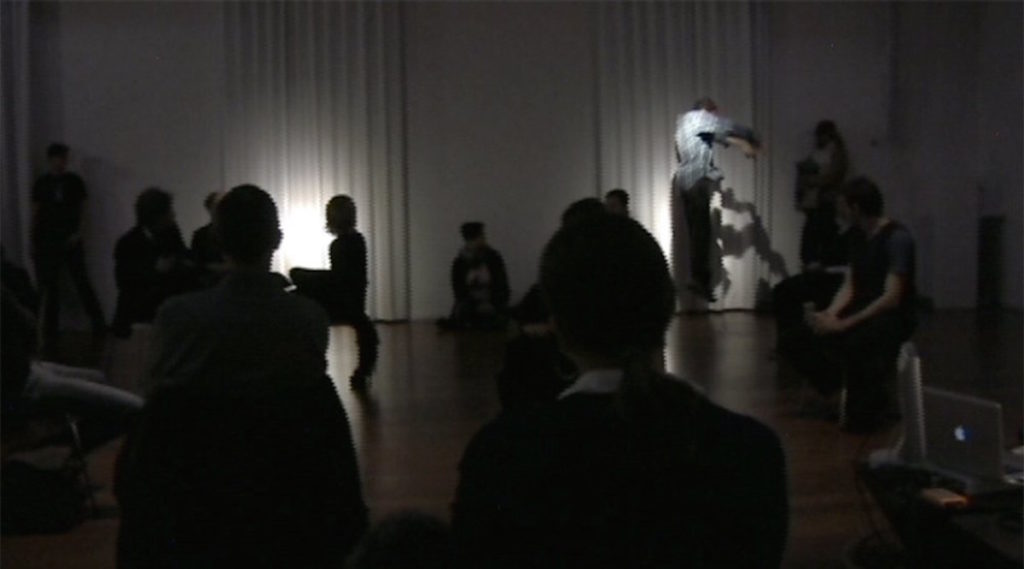

Space, movement and belonging are themes Waxman returns to in Mechitza Project (2010), a collaborative installation with dancer Jesse Zaritt and composer James Hurley at Kulturlabor ICI Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry.

The Mechitza is a partition in (some Orthodox) Jewish synagogues which separates men and women in the congregation. The name of the work is evocative in its instant association with division and boundaries–connotations which may become more pertinent as we learn, from the artist statement, that the work itself is a “post Zionist critique.” The installation combines live sound design/motion tracking technology with a composed soundscape and choreography. The audio clips that comprise the soundscape are recordings made by the artist in occupied territories of Palestine, and in Chassidic men’s prayer spaces in New York. The juxtaposition of these two contexts may provoke consternation, perhaps even controversy, however, the layering of these diasporic sounds in a new, third context raises thought provoking questions for the viewer. Through the interaction of space and sound, an auditory architecture is created, and invisible boundaries are drawn. Participants are seated and standing throughout the space while a performer moves around them and industrial, harsh tones are played interspersed with eerie silence and muffled vocals.

The performance not only suggests, again, a sense of separation and longing, but of the surveillance that accompanies such close scrutiny of movement. It’s unclear, from the outside, whether the spectators have any control over the movements of the dancer, or if they are passive spectators.

Even outside of a geo-political context, this piece questions the nature of a gallery space as a space of compliance and covert surveillance and judgement of each other.

Shirley Ardener, a pioneer of women’s studies, posited that “any restricted area…has rules determining its boundary, how it shall be crossed, who can occupy that space,” whether it is a nation-state or an art institution. And as with any exclusive space, people seeking entry must “meet certain kinds of criteria (become a member, buy a ticket, get a visa, pass a citizenship test) and each has a gate-keeper.” The Mechitza Project can be seen as a microcosm for the wider social and political issues Waxman and their collaborators are referencing, including contested space and how its inhabitants are implicated.

Waxman’s latest project, currently in progress, is Gender Diaporist. This work follows the artist’s journey applying for Polish citizenship (through a Jus Sanguinis, or “right of blood” claim) as a transgender, Jewish person of Polish heritage. This is a timely project, as divisions along ethnic, religious, political and social lines continue to deepen across the Globe, and policing of people’s identities as citizens, or as a particular gender, is increasingly entangled with opaque bureaucracy, algorithms and data collection technology.

All three works strongly represent a theme of Waxman’s artistic practice–identity. Whether negotiating segregated religious space as a gender non-conforming person in the Amidah Triptych, questioning the insidious and sometimes invisible nature of borders in the Mechitza Project, Tobaron Waxman’s work encourages us to ask questions of ourselves, our beliefs and how we view the world.

Image depends on its subscribers and supporters. Join the conversation and make a contribution today.

+ Click here to make a donation.

+ Click here to subscribe to Image.

The Image archive is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Written by: Maryanne Saunders

Maryanne Saunders is a PhD researcher at King's College London focusing on gender, sexuality, and language in contemporary religious art. Her work has appeared in Times Higher Education, The Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception and the edited volume Encounters: The Art of Interfaith Dialogue. Follow her on Twitter @maryanne_fs