IN AGNES PELTON’S White Fire (1930), a deep blue void splits in two to reveal pulsing ribbons of light. Three cosmic eyes stare back at the viewer, beckoning from the threshold of the visible realm. A veil wavers between us and whatever lies beyond, and we feel an eerie sense of someone looking back at us, inviting us to cross over to the other side.

It’s one of many images Pelton made intending to “widen the horizon of art” toward “spiritual planes” (in the words of her Transcendental Painting Group manifesto), and it appeared recently in Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art (2022), a traveling exhibition featuring over one hundred artists who, according to the wall text, “make visible their experiences with the supernatural world.” Gathering work from the early nineteenth century to the present, the show tells this story through loose themes like “Imagining the Unseen” and “Spirit Artists,” grounding the artworks in American spiritualism, a movement that involved making contact with the dead through séances and mediums.

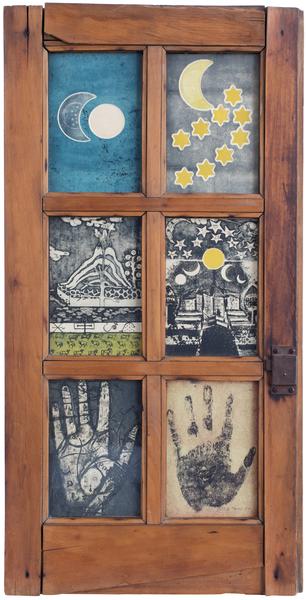

Betye Saar. The View from the Sorcerer’s Window, 1966. Assemblage of color and intaglio etchings and wood window frame. 30 x 15¼ x 1½ inches. Collection of Halley K. Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. Appeared in Supernatural America.

Forty-four years earlier, curator Maurice Tuchman mounted another show with supernatural themes: The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985. The show displayed over two hundred works at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and sought to explore art-historical “connections with occult and mystical belief systems” like Zen, the kabbalah, and tantric practices. The influential and out-of-print catalog features essays exploring the effects of these ideas on European artists, a glossary of esoteric terms, and short biographies teasing out artists’ spiritual histories. The catalog especially emphasizes theosophy, a philosophical movement that sought hidden knowledge within the world’s religions, and quotes often from Wassily Kandinsky’s classic text Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

In 2020, All of Them Witches opened at Jeffrey Deitch’s Los Angeles gallery, featuring close to eighty artists making work with a “witchy sensibility.” The curation was deliberately unstructured, downplaying historical context and sharing work by practicing witches, work that merely looked spooky, and everything in between. It loosely grounded contemporary works against a backdrop of artists from the 1970s, like Ana Mendieta, who created an “iconography of the supernatural” intimately connected to feminist concerns.

On the surface, these three exhibitions have their differences. Supernatural America focused on diverse American artists who wanted to connect with a spiritual realm beyond the physical one, while The Spiritual in Art dealt more with white, male European artists exploring the religious arcana of other cultures. And where All of Them Witches was inclusive, playful, and deliberately non-hierarchical, Supernatural America and The Spiritual in Art were carefully organized around histories and themes.

Guadalupe Maravilla. Disease Thrower #3, 2019. Gong, steel, wood, cotton, plastic, loofah, and objects collected from a ritual of retracing the artist’s original migration route. 96 x 57 x 63 inches. Courtesy of Guadalupe Maravilla and P·P·O·W, New York. Work from this series appeared in All of Them Witches.

Each show reaches for its own defining language, using words like paranormal, esoteric, or witchy to hold together its dizzying range of beliefs and practices. Combined, these shows explore anthroposophy, apparitions, automatic writing, hermeticism, kabbalah, magic, mediumship, paganism, phantasmagoria, shamanism, spiritualism, tarot-reading, ufology, vodou, witchcraft, and more. Despite their varied subject matter, time frames, and curatorial choices, these shows are surprisingly similar in their approach to the intersection of spirituality and art.

More than a subject matter, these shows approach spirituality as a dimension of artmaking itself. In his introduction to The Spiritual in Art, Tuchman claims that theosophy is bound up in the origins of abstract art, a framework that unified aesthetic and spiritual aims. In his catalog essay, Supernatural America’s curator, Robert Cozzolino, writes that engaging spiritualism changes the meaning of curatorial work itself, “decentering the traditional Western position of authority” in order to take its spiritual ideas seriously. “It demands a practice of listening to and learning from the intelligence and wisdom of diverse knowledge systems.” Meanwhile, the “witchy sensibility” of All of Them Witches gathers a broad collection of artists using witchcraft and other occult imagery as a means to address issues of power and gender.

These shows, then, aren’t so much about spirituality as they are evidence of how artists and curators understand the spiritual dimensions of their own work. So while certain spiritualities are framed as marginalized “diverse knowledge systems,” they function more as sources of inspiration for artists and curators than rediscovered ways of knowing. While this certainly demonstrates an interest in esoteric spirituality on the part of museums and galleries, it remains to be seen how genuinely diverse this engagement will be.

While this focus on spirituality might seem like a trend, these three exhibitions are part of an ongoing history of group shows on spiritual themes. In 2008, Centre Pompidou organized Traces du Sacré, an exhibition interpreting the work of over two hundred international artists through loose cosmic themes like “Doors of Perception” and “Nostalgia for the Infinite.” Even the Centre’s Magiciens de la Terre (1989), an exhibition that sparked global debates on colonialism and art, did so under the banner of “magic,” with curator Jean-Hubert Martin suggesting in an interview that the artists’ common “search for spirituality” was what helped unite the show. In 2004, Los Angeles artists John Baldessari and Meg Cranston curated 100 Artists See God, a traveling exhibition that sought to transcend “universal images of traditional faiths to offer individual interpretations of spirituality.”

These exhibitions, then, not only explore spirituality as a subject matter but offer up making and appreciating art as its own spiritual experience independent from religious traditions—often quite explicitly, as in MCA Chicago’s Negotiating Rapture: The Power of Art to Transform Lives (1996), where the exhibition’s own floorplan was designed in the shape of an infinity symbol.

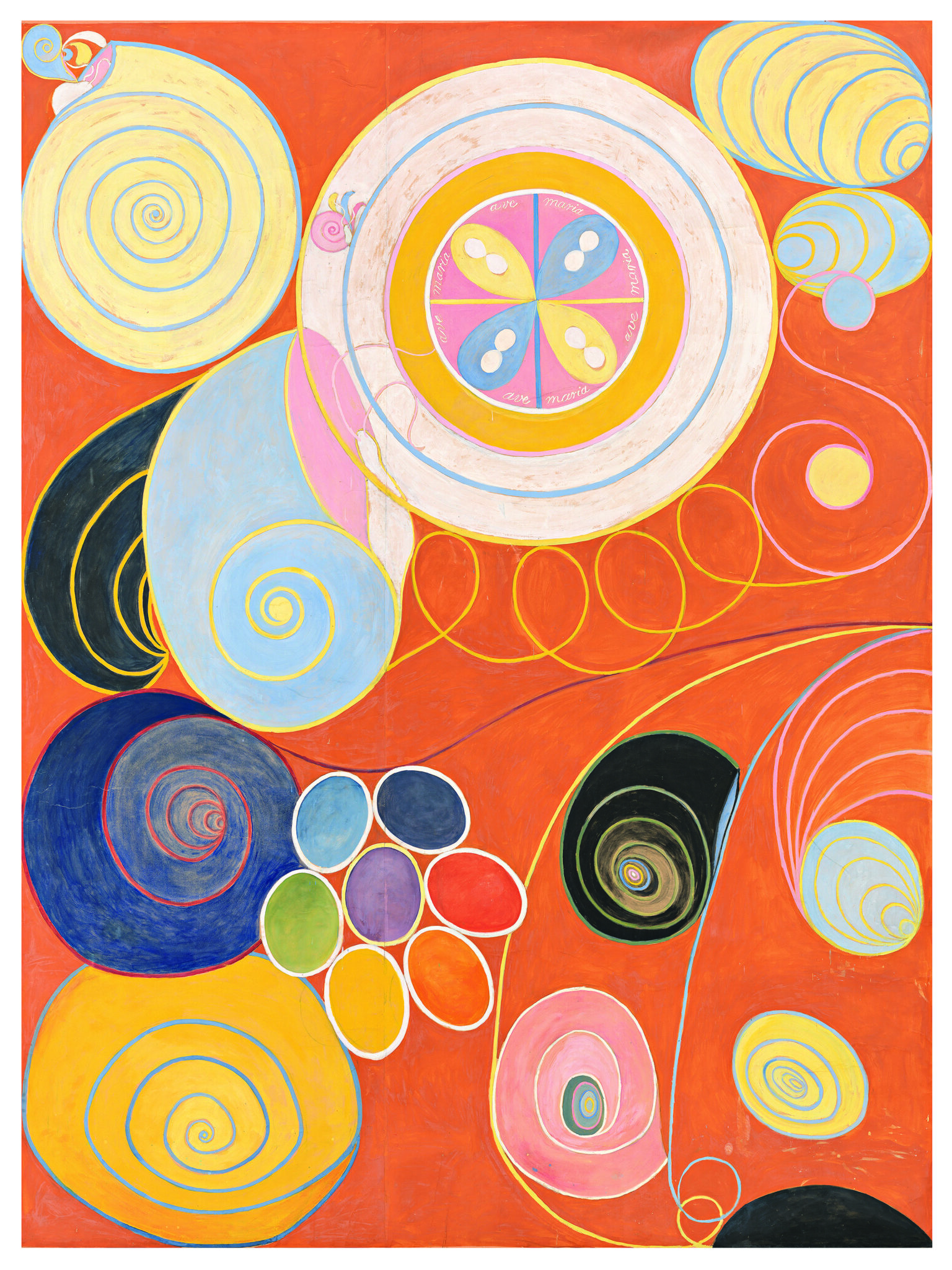

Hilma af Klint. Group IV, the Ten Largest: No. 3, Youth, 1907. Tempera on paper, mounted on canvas. 129 x 94 inches. Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Moderna Museet Stockholm. Appeared in The Spiritual in Art; works from the same series appeared in Traces du Sacré.

So, what holds together this curation of the “infinite” and “otherworldly,” the “enrapturing” and the “magical”? To begin, all of these shows assume an undefinable supernatural dimension to life. Their terms imply an open-ended sense that there exist other realms beyond this one, inaccessible through ordinary sense perception and language. Also, most of these shows are committed to displaying work from marginalized traditions, broadly conceived. Finally, they all share a commitment to unrestricted creative freedom as artists explore these traditions in whatever ways they see fit. So, whether the topic is spiritualism, theosophy, witchcraft, or anything in between, these exhibitions tell a singular story, one in which individual artists translate spiritual phenomena into material form on their own terms. It’s a distinct approach to spirituality—a tradition—that easily maps onto the commitments of museums and galleries, spaces that often celebrate individual artists and their ability to embody larger cultural themes.

However, this curatorial tradition quickly runs into a problem: how do you emphasize contemporary artists’ unique access to supernatural realms in a world full of established religions—sources of aesthetic and spiritual inspiration in their own right? Given that the great world religions exist, how can artists claim their own unique spiritual authority? Conscious of this problem, Supernatural America explicitly claims in a wall text that many artworks emerged from traditions that “developed apart from, but conscious of, Christian religious practices.” Tuchman, Baldessari, and Cranston all make a clear distinction between institutional and individual beliefs, largely ignoring the former in favor of the latter. All of Them Witches curators Dan Nadel and Laurie Simmons separate image from action, stating plainly that while they “respect the history and context of real-practice occult,” their focus on the “aesthetic influence” on artists gives them license to ignore it. Finally, other shows try to distinguish the influential present from the distant past. The first room of Traces du Sacré featured a painting of cathedral ruins at sunset—a not-so-subtle visual move to separate the concerns of the show from what is framed as a crumbling Catholic past no longer influencing the present. In its own way, each of these approaches seeks to isolate the type of spirituality the show wants to pursue from the complicating influences of tradition, practice, or history.

So what are these distinctions for? Why bracket certain elements if the shows are committed to such a diverse range of spiritualities? Interpreting spirituality in loose terms might seem like a way to protect the creative freedom of the artist and curator. But by the very fact of their existence, religious traditions (with their own texts, practices, and generations of artists and believers) call this approach into question: the landscapes of spirituality are well-trodden. The problem, then, is not with separating an artist-centric approach to spirituality from religious traditions in general but that these curatorial choices obscure the fact that both approaches continue to coexist, each influencing the other regardless of attempts to separate them. So in an attempt to isolate spirituality from more mainstream traditions, what’s left isn’t some neutral aesthetic space but a peculiar kind of haunting—a haunting that affects how we appreciate the artworks themselves.

Norman Lewis. New World A’Coming, 1971. Oil on canvas. 73 x 87 inches. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. Appeared in Supernatural America.

To start, when curators and artists try to isolate spiritual imagery and ideas from religious sources, they’re often cutting themselves off from what could be sources of wisdom. The nineteenth-century American spiritualists were certainly not unique in their belief in a supernatural realm. Theosophical societies didn’t so much as discover spirituality as curate it into new forms. Each ancient religious tradition has centuries of diverse writers and thinkers who inspire the searching of many artists, regardless of their commitments. Temples, synagogues, churches, and mosques have been passing down these ideas and practices for millennia. How might museums and galleries receive them as gifts?

Beyond ignoring the possibility of shared wisdom, trying to isolate art from religious communities can also leave artists and institutions vulnerable to re-creating what already exists. Shows that claim to discover spirituality are often unknowingly repackaging what humans have been exploring for centuries. One interesting example is the holistic programming of Compound Long Beach. The gallery identifies as a “cultural sanctuary” focused on belonging, justice, and spiritual practices like yoga and meditation. Could such an institution meaningfully partner with a traditional religious community to draw on millennia-old resources on spiritual practices?

These are largely benign issues, but these separations can also lead to interpretive problems within the shows themselves. All of Them Witches obscured Janine Antoni’s critique of Catholicism and Shirin Neshat’s feminist exploration of Islam—flattening their work into vague witchy vibes. And then there is the slightly different problem of projecting religious systems where they don’t belong, as in The Spiritual in Art, where one catalog writer sees astrological signs in Gauguin’s The Yellow Christ and sacred geometry in Maurice Denis’s image of the Eucharist, while appearing uninterested in the actual sources of the iconography present in the works. When these religious influences are ignored, a painting can be entirely misinterpreted, as in Norman Lewis’s New World A’Coming. According to Supernatural America, its swirl of abstract figures is a “futurist image of Black life,” its bright gleaming orb a UFO drawing people forward—and the work was prominently displayed in the show’s “Plural Futures” room. Lewis, however, influenced by his upbringing in the Black church, was not imagining a celestial future but joining an ongoing dialogue with the past: the title comes from a spiritual sung by enslaved men and women as they interpreted their own suffering through the exodus narrative of God leading the Israelites through the wilderness. Far from limiting an artist or curator’s freedom, becoming more aware of these traditions and their influence only adds clarity and depth to the work of interpretation.

Finally, there is a more disturbing colonizing undercurrent to these separations between traditional, communal approaches to spirituality and their more experimental forms in art circles. Art history is filled with people taking artworks out of context and displaying them in order to reinforce unacknowledged hierarchies. Museums and galleries have worked diligently in the past few decades to address their part in perpetuating these tendencies, especially with attention to race and gender. But trying to separate religion (tradition-bound, constricted, bad) from spirituality (open-ended, enlightened, good) perpetuates similar hierarchies. If spirituality is ahistorical and emerges from the self, it can be appropriated without concern for social context. In this way, the desire to elevate lesser-known spiritual ideas paradoxically reenacts the very moves it seeks to redress: in the name of decolonizing one tradition, artists can appropriate cultural property from others. Mary Beth Edelson’s Women Rising (1975–77) from Supernatural America comes to mind, a quilt-like work gathering names and images of female deities from across time and space in order to support the feminist concerns of American artists. Whatever meaning these deities had in their original communities is unclear; the new context is all we see. The spiritual biographies of artists, too, can be flattened. In the same show, Henry Ossawa Tanner’s African Methodist Episcopal background and Hyman Bloom’s Jewish background are likewise downplayed in favor of interpretations more amenable to Supernatural America’s paranormal themes.

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer. And the Kingdom Is Here, 2020. Oil on canvas. 65 x 85 inches. Appeared in All of Them Witches.

These problems aren’t the result of curators’ worthy commitment to protecting artists’ freedom as they explore spiritual ideas. Rather, they arise when this commitment is assumed and when spirituality is seen as a topic unbound by history, practice, and tradition. Spirituality often emerges from religious sources that don’t always fit within curatorial frameworks, and these traditions have their own distinct influences on the meaning and practice of artmaking today. Each of these shows is eloquent in its own way; they all take risks as they ground the meaning and purpose of artmaking in supernatural realms. But it’s worth drawing out these curatorial frameworks in order to see how that framing constitutes its own tradition—for the good of artists, curators, and larger religious communities all interested in the spiritual dimensions of art.

Exploring the overlapping worlds of spirituality and the arts is neither a trend nor an anachronism. More than “revealing” or “recovering” spirituality for the first time, these shows and others like them are evidence of an ongoing conversation—and people within both religious and art traditions doing patient work. It’s a complex and rewarding entanglement, involving many distinct communities who, if they press against the veil, might find others pressing back.

Michael Wright is a writer and teacher with an MA in theology and the arts from Fuller Seminary. He writes Still Life, a weekly letter on art and spirit, and his work has appeared in Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles, Ekstasis, Nations, The Curator, and others.