REFLECTING ON SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ART of the last century, I have come to regard the period of 1985 to 1995 as “the disparate decade.” In those ten years, postmodern attitudes suffused the art of the region, upending modernist strictures, opening up a panorama of expressions, and extending a horizon of possibilities. A kind of wild blue yonder, it was a heady and confusing time for young artists launching their careers. Critics struggled to find a vocabulary to address new and unconventional work, while gallery- and museumgoers found themselves by turns delighted, perplexed, and outraged.

Amid this turbulence, Duncan Simcoe completed his MFA in 1987 at California State University, Long Beach, one of the stronger painting programs in greater Los Angeles. The 1980s also saw California art finally getting the national recognition it deserved. Richard Diebenkorn (1922–93), who painted first in Santa Monica and later the Bay Area, was finally assessed in terms usually reserved for New York artists.

Duncan Simcoe. Candelabra, 2019. Oil on tar paper. 80 x 39 inches. All photos by Christopher Kern.

I mention Diebenkorn because Simcoe acknowledges a debt to him. When Simcoe saw a local retrospective of the artist’s work in 1985, he recognized a kindred spirit, one that confirmed him in his own goals. Both artists made composition their paramount consideration. Both grounded their paintings in underlying drawings vigorously sketched. Both used prominent spatial planes to structure and activate their imagery. And both favored broadly applied areas of color briskly brushed onto the canvas.

But here the similarities end. Up to the late 1960s, Diebenkorn worked with the figure, still life, and landscape. He then turned to abstraction, although his pictorial arrangements continued to allude to the landscape and the effects of natural light upon it. By contrast, Simcoe favored depicting recognizable subjects filtered through a mystical and poetic sensibility. In addition, he was part of a small contingent of Southern California artists—including Lynn Aldrich, Daniel Callis, Roger Feldman, Wayne Forte, Barry Krammes, Laura Lasworth, Michael Schrauzer, and Patty Wickman—who were convincingly using contemporary modes to express their Christian faith. Simcoe’s work stood out both in its narrativity and its social awareness. (For more on his early work, see my 1994 essay in Image issue 8.)

Duncan Simcoe. The Black Box, 2014–22. Three-piece installation. Oil on tar paper. Each 20 x 40 x 50 inches.

Duncan Simcoe. The Black Box, 2014–22. Three-piece installation. Oil on tar paper. Each 20 x 40 x 50 inches.

Duncan Simcoe. The Black Box, 2014–22. Three-piece installation. Oil on tar paper. Each 20 x 40 x 50 inches.

Duncan Simcoe. The Black Box, 2014–22. Three-piece installation. Oil on tar paper. Each 20 x 40 x 50 inches.

By 2005, however, Simcoe had grown frustrated with the pace of his production, although he continued to create paintings that met his aspirations. Geography was part of the problem. He retained a studio in downtown Los Angeles but was living and teaching in Riverside, some fifty freeway miles to the east, allowing him only two days per week of studio time. The long drive, combined with the time-consuming process of acquiring costly canvas, stretching it on made-to-order frames, priming the surfaces, penciling in imagery, mixing oil pigments, and rounds of cleaning up—all were getting in the way of exploring new and pressing ideas. Simcoe realized he needed to create his images more directly and quickly.

One day while poking around his studio, he chanced upon a roll of black tar paper (an industrial product used in housing construction), acquired earlier for a long-forgotten reason. Simcoe instinctively recognized its potential as the medium he was seeking. It had a texture receptive to crayon and brush; its lusterless, inky finish conveyed an aura of mystery; and you could simply tack it onto a gallery wall for display. Attentive to art history, he recalled his fascination with Francisco Goya’s so-called Black Paintings, produced in the final years of his life. In their forbidding and enigmatic content and palette of murky black, spectral white, and sallow flesh tones, these private inventions defied all artistic conventions of their era and continue to astonish viewers. Contemplating the Spaniard’s Black Paintings almost two hundred years after their creation, Simcoe saw how a constrained palette on a black ground could become his next body of work.

Francisco Goya. A Pilgrimage to San Isidro (detail), 1820–23. Oil on canvas. 4½ x 14 feet. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Another precedent also foretold this direction. In 1998 I attended a lecture Simcoe presented at the UCLA Armand Hammer Museum titled “The Need for the Dark.” Offering the provocative assemblage artist Edward Kienholz (active in LA from the 1950s to the 1970s) as an example, Simcoe contended for an art willing to engage with the painful realities of American life. Eschewing traditional fine-art materials, Kienholz gained notoriety for the unsparing social commentary of his assemblages and three-dimensional figurative tableaux composed of components salvaged from junkyards. I believe Kienholz would have endorsed the younger artist’s use of tar paper.

Throughout the 1990s, Simcoe had produced a layered and forceful series of paintings, collages, and an installation that braided the Genesis narrative of Abraham and Ishmael with reflections on Black American life, sometimes incorporating the Civil War as backstory—this during a period when American historians were finally beginning to address that conflict’s racial origins.

Early in the aughts, Simcoe sensed that he had reached closure with that series and was now certain that black tar paper was the most promising medium to pursue new directions. After some experimenting, he launched himself into a body of work he has since called the Black Drawings. From now on he would draw his imagery with oil paint and brushes—though the linear quality of his work might make the viewer believe he was using crayon or pastels.

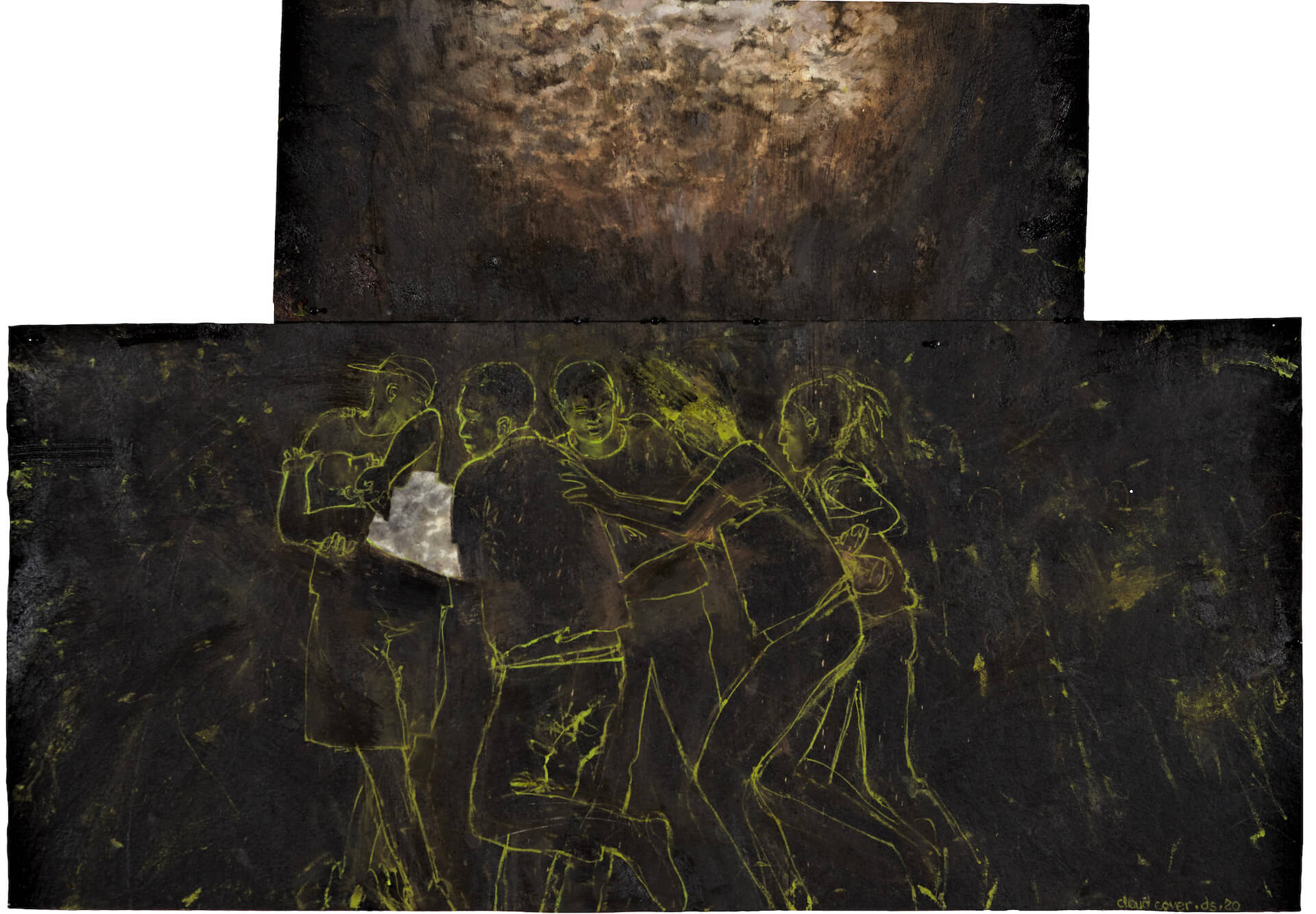

Simcoe soon discovered that working on tar paper produced imagery that held in tension haunting and luminous sensibilities. Cloud Cover is composed of two sections, or zones, of tar paper. Unequal in size, the pieces are also disparate in content. The bottom section is an unsettling figurative tableau in the scruffy style of Kienholz but also evoking the early socially aware work of sculptors George Segal (1924–2000, especially his monochromatic figure groupings) and Duane Hanson (1925–96) and the painter Leon Golub (1922–2004), whose brusquely limned narrative images and surfaces parallel Simcoe’s work. (Eschewing frames and with a rough-and-ready approach, both Simcoe and Golub tacked their works to the wall.) Cloud Cover depicts a group of young people frozen in their rush across the picture plane, bearing the body of a fallen comrade. While the grouping of figures is taken from an old Life magazine photo of civil unrest in Santo Domingo in the 1950s, Simcoe has transformed it into a Christian meditation on death and resurrection.

Duncan Simcoe. Cloud Cover, 2021. Oil on tar paper. 60 x 85 inches.

The top section of Cloud Cover is filled with a glowing and mysterious spherical mist. This is not the bright, frothy cumulous heaven inhabited by cherubs, angels, and the Holy Trinity rendered in abundant glory by generations of Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo painters. Simcoe’s cloud seems more in tune with theologian Rudolf Otto’s sense of the holy as an encounter with the divine that is simultaneously terrifying and fascinating—the mysterium tremendum et fascinans. In this light, the fervid body bearers in Cloud Cover are a means of conveyance for the heavenly transition of their friend.

This notion fired Simcoe’s imagination, and it eventually led to a series of free explorations coming together as a body of work he formally dubbed Means of Conveyance. An iconic example is Meet Me, an imposingly narrow, seven-foot-tall painting of two sections of a spiral staircase abutting each other [see detail on front cover]. Though the human figure is absent, its presence is implied. One can easily imagine people ascending and descending upon the serpentine steps, or even angels going up and down as in Jacob’s dream. But I also wonder if the title suggests the ultimate Transcendent Encounter along the twists and turns of life.

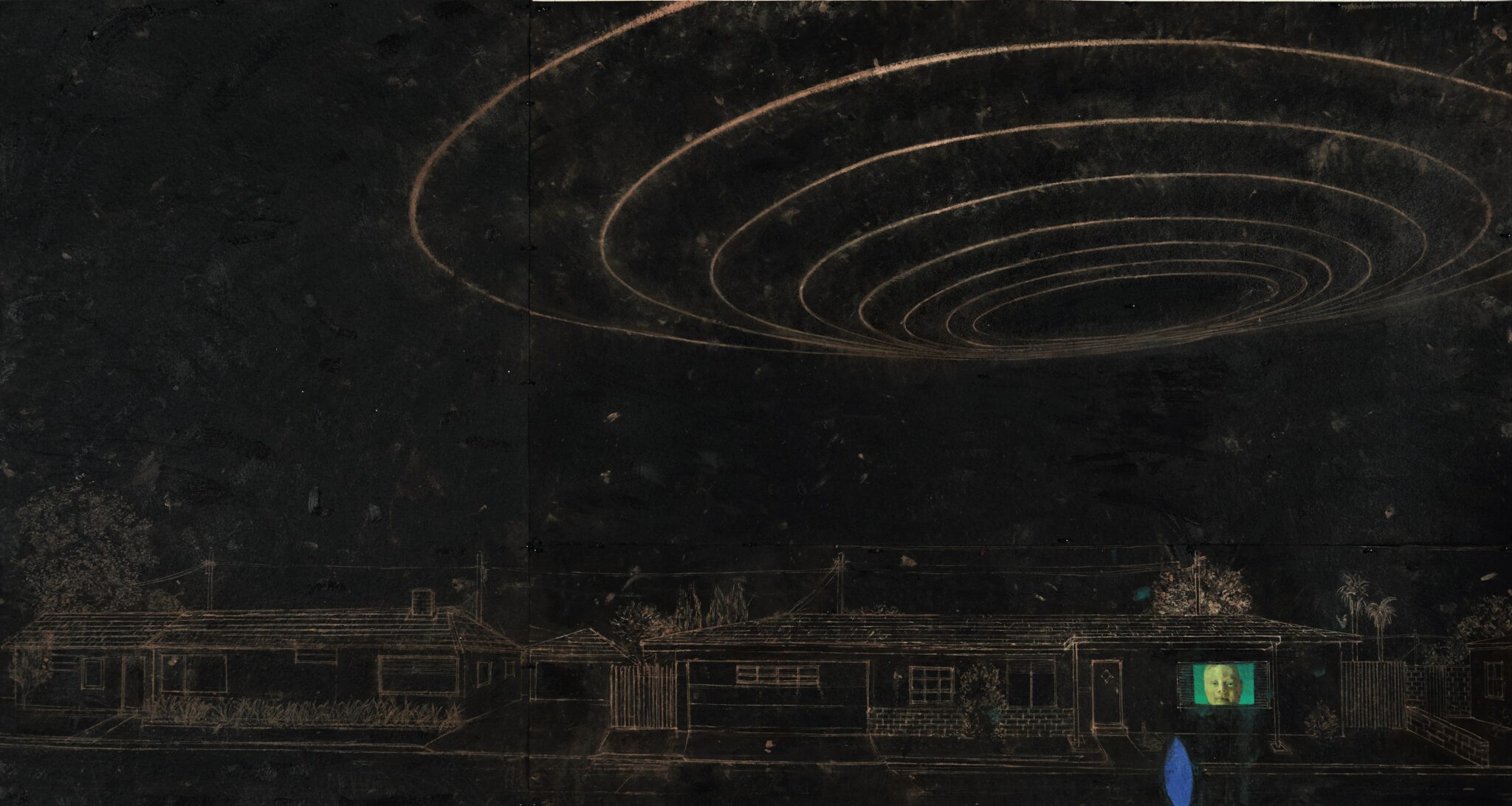

Duncan Simcoe. Mythinburbia #10 (Mr. Vortex), 2015–22. Oil on tar paper. 59 x 111 inches.

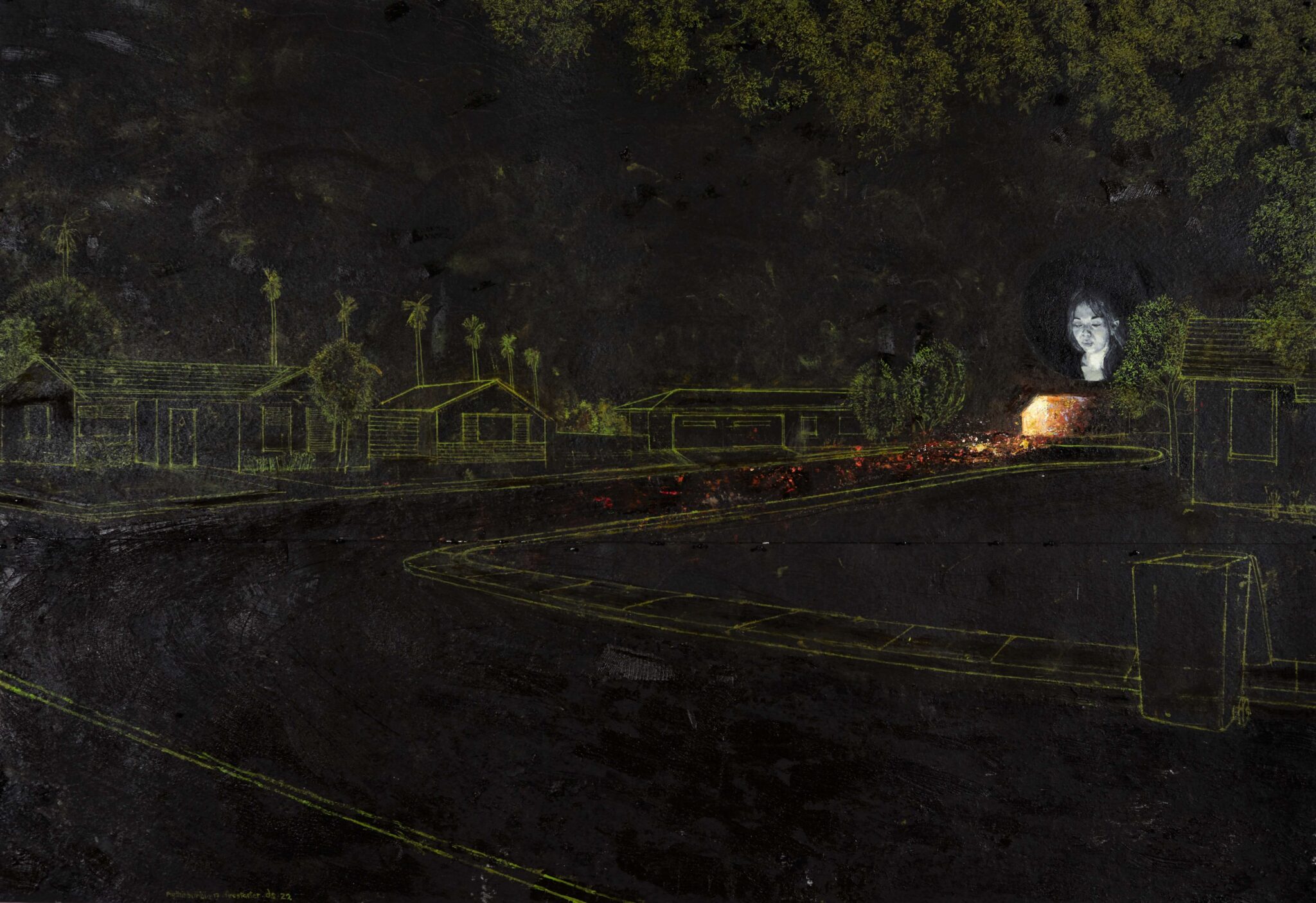

Duncan Simcoe. Mythinburbia #17 (Fire Starter), 2022. Oil on tar paper. 63 x 96 inches.

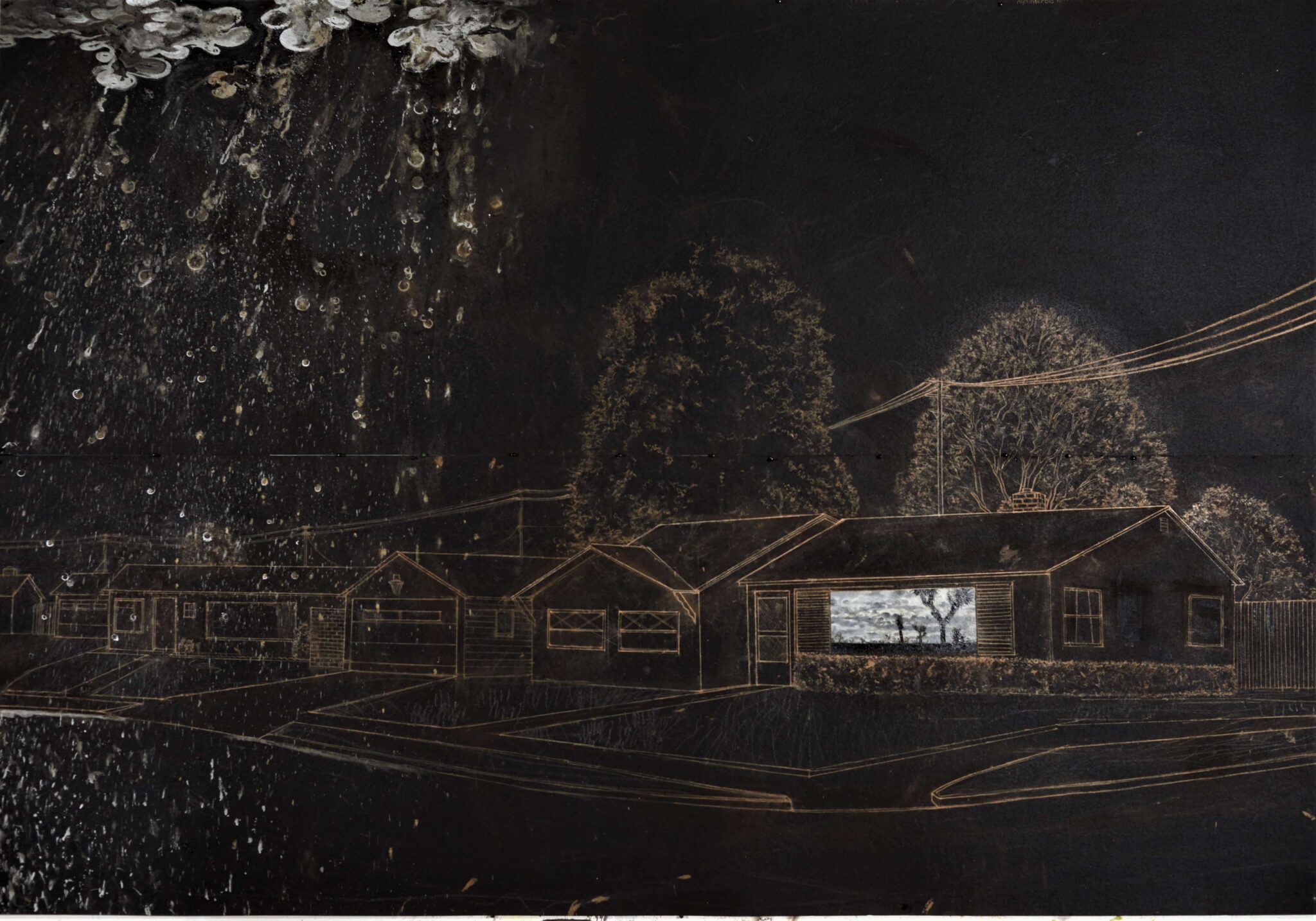

Duncan Simcoe. Mythinburbia #13 (Rain in the Desert), 2017. Oil on tar paper. 79 x 115 inches.

As Simcoe continued his experiments with tar paper, a sensational event captured his imagination: On March 8, 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight 370 altered its northbound flight path to Beijing without warning. Veering sharply southwest and ceasing communication, the Boeing 777 flew off course for some six hours before plunging into the Indian Ocean. Two hundred and thirty-nine people perished. In the search that followed, the focus was on retrieving the plane’s flight recorder, the so-called black box. The passenger jet was never found.

Simcoe was haunted by this tragedy and concluded that there was an image that could respond to it. He fixed on the black box as his concept. “Finding it was supposed to explain everything, to make the mystery go away, providing reassurance to an anxious world,” he told me. “I then realized that I could construct my own ‘black box’ out of a thick stack of 239 sheets of black tar paper, one for each of the people lost.” Simcoe’s The Black Box is an installation presented as a series of three rectangular heaps of tar paper. The top sheet of each stack bears a symbol representing a major world religion. For Islam, there is a double-pointed oval, the central shape found on Muslim prayer rugs. Isolated on the black background, with tiny flecks of reds, oranges, and yellows glinting like sparks from within the black field, the shape also resembles a carved jewel. For Hinduism, the god Shiva is depicted doing his iconic dance, symbolizing both his labors to overcome ignorance and the continuous cycles of creation and destruction. Simcoe shows him pirouetting atop a globe of shimmering waves—evocative of the oceanic depths that hold the passenger jet. A nude Adam and Eve represent Christianity. They could also be a Jewish image, of course, but the context ties these particular figures to Christian doctrine: Simcoe appropriated the pair from the renowned early-fifteenth-century Ghent Altarpiece by the Flemish Van Eyck brothers, Hubert and Jan. Like the originals, his Adam and Eve have just realized the consequences of their sin and gaze downward introspectively. Their appearance on one of the black boxes seems to signify a fallen humankind’s limited capacity to comprehend catastrophes like flight 370.

Richard Diebenkorn. Ingleside II, 1963. Oil on canvas. 29¾ x 70 ½ inches. © Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

I also wondered if the three black boxes serve as a kind of ecumenical theodicy—Simcoe’s rumination on how a good God can permit manifestations of evil—the why of fatal disasters. Seen in this light, could the mournful Black Box be a kind of memorial? In a gallery installation the stacks could be seen as a trio of coffins—the victims of flight 370 lying in state, bringing the visitor to silence and perhaps prayer.

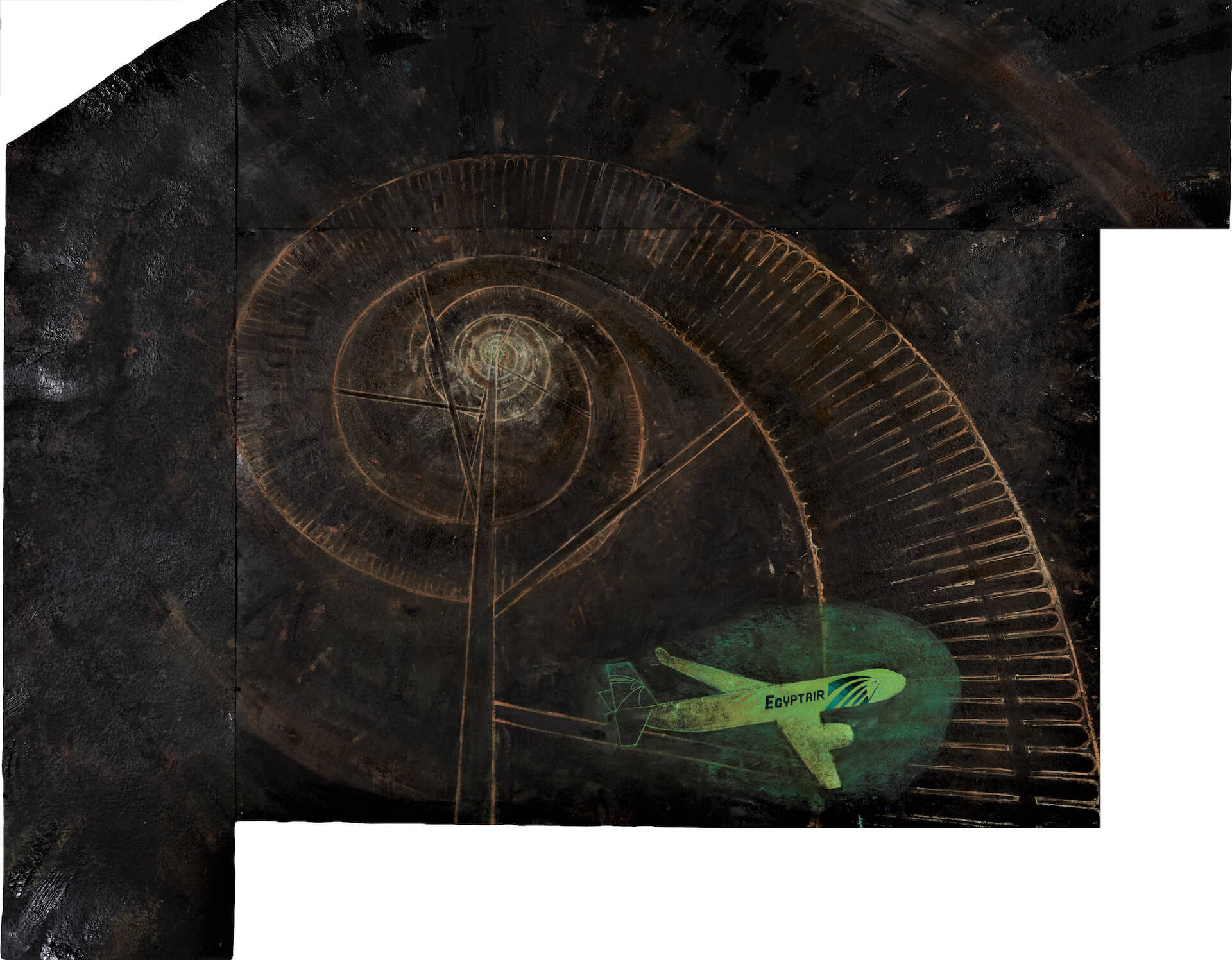

A parallel sensibility informs Simcoe’s black drawing Egypt Air (Saint Catherine Leaves the Planet), inspired by the notorious crash of Egyptair flight 990 in 1999. Like Malaysia Airlines flight 370, the Egyptian passenger jet inexplicably plunged into the ocean. As the plane prepared to depart from Kennedy International in New York, the captain addressed his flight crew: “In the name of God, the merciful, the compassionate. Cabin crew takeoff position.” Once in the air, the captain turned over the controls to the first officer and left the cockpit. Within minutes the eastbound plane went into a nosedive, then briefly recovered, only to resume its plummet into the Atlantic Ocean. All 217 passengers and crew perished.

In pondering how to respond to this tragedy, Simcoe drew upon the legend of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, who was martyred circa AD 310. Born in Egypt during the reign of the Roman emperor Maxentius, while still a teenager Catherine devoted herself to serious study, during which she received a vision of the Virgin Mary and the child Jesus. She responded by becoming a Christian. According to tradition, she confronted the emperor for his brutality in persecuting Christians, boldly proclaiming the gospel against the imperial pantheon. Her forceful apologia led to her martyrdom, which inspired some two hundred Alexandrians to convert. They suffered the same fate as Catherine. Since the early Middle Ages, she has been venerated by the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches for her intercessory power and (ironically) invoked against sudden death.

Duncan Simcoe. Egypt Air (Saint Catherine Leaves the Planet), 2017. Oil and encaustic on tar paper. 65 x 81 inches.

Simcoe composed Egypt Air upon three variously sized sections of tar paper joined together—a kind of analogy to the post-crash report assembled by the National Transportation Safety Board. He painted a murky atmosphere onto the tar paper, and then drew a spiral that recedes into a central point of soft flickering light. Journeying into this vortex, the Egyptair jet carries its crew and passengers into eternity—a transmigration of souls. The plane is illumined by an eye-shape of translucent emerald green, as though seen through night-vision goggles. By evoking Catherine of Alexandria’s hagiography, Simcoe’s mysterious image connects the 217 airliner deaths and the 200 Egyptian martyrs inspired by the saint’s faithful witness in the fourth century. Moreover, pious legend tells of Catherine’s corpse being flown by angels to Mount Sinai, the ancient Eastern Orthodox monastery that bears her name. This painting is also part of the Means of Conveyance series.

For Simcoe, his most important work yet on tar paper is his current series, Mythinburbia. He coined this neologism to describe his infusion of nondescript and broad renderings of Orange County ranch-style homes with cosmic, mystical, and religious imagery. What he calls the “immense secularity” and soullessness of the postwar Southern California suburbs provides an optimal backdrop for his poetic, social, and theological provocations. To obtain source material for Mythinburbia, the artist travels through subdivisions to photograph wide street views to adapt for his compositions. Only this year did Simcoe learn that Richard Diebenkorn did similar research in the early 1960s for his series of paintings of the San Francisco suburb known as the Ingleside Terraces. In a curious coincidence, Simcoe’s Mythinburbia and Diebenkorn’s Ingleside series show how both artists prioritize organizing the planes of lawns, undulating streets, and ranch-style houses into a horizontally structured geometry of forms. While Diebenkorn found in the Ingleside tract the basis for creating abstract compositions as ends in themselves, Simcoe’s suburbs are the settings for spiritual and psychological narratives.

Hugging the bottom of the picture plane, Mythinburbia #10 (Mister Vortex) portrays the stark horizontality of a residential street in a colorless, diagrammatic fashion. In an alarming contrast, a wide, spiraling vortex intrudes from above, recalling the gargantuan disc-shaped spaceships from the 1996 film Independence Day. Playing upon the disparity of the mundane and cosmic (or spiritual) throughout the Mythinburbia series, Simcoe intervenes with what he calls “mystical punctuations.” As our gaze drops from the ovoid maw of the vortex, we note that the picture window of the house below is filled with a bright green rectangle framing the head of a child who stares out imploringly. Typically, tract houses are set back from streets and sidewalks by needless lawns; there are no porches on which to take one’s leisure or greet neighbors and passersby. Suburban dwellers are literally sheathed in quotidian isolation—even as eternity descends.

Simcoe took up the notion of suburbia as a desert in Mythinburbia #13 (Rain in the Desert). Using a straightedge, he meticulously drew a residential street view that hearkens more to the abstract precision of a blueprint than a place where people experience joys and sorrows. In the foremost house, he has placed a very wide picture window onto the (perhaps ironically named) living room. Therein we see an actual desert landscape—gray, flat, and sparsely dotted with Joshua trees. Upon closer view, we notice that the desert sky is filled with storm clouds; desolate wastelands eventually do get some rain. Does the picture-window image prophesy life-giving showers for Simcoe’s arid suburbia? At the upper left, roiling globby clouds intrude to unleash a messy downpour—metaphorically vivifying much more than the neighborhood’s lawns.

As Simcoe continued his Mythinburbia tar paper drawings, he found new metaphors in his medium and compositions. And while he produced fresh imagery to critique the isolation, banality, conformity, and cultural barrenness of suburbia, he realized, in artistic terms, that he was plowing the same row that sociologists, anthropologists, and cultural critics had done for decades. Was a truly novel engagement with suburban iconography possible? Why not portray suburbia as a site for reawakening?

Drawn in a dreary lime green, Mythinburbia #17 (Fire Starter) lays out a residential expanse where a cul-de-sac branches out from the main thoroughfare—a dead end by design. In the right foreground Simcoe has prominently placed an empty garbage bin—a sly comment on the acquisition-disposal cycles of consumerism. The tenebrous composition, however, is ignited at the end of the cul-de-sac where a residence is mysteriously consumed with a broiling glow. In the air above, a mysterious sphere hovers in which a young woman forcefully exhales upon the house, sending a surge of brilliant sparks and embers along the street. Is she a mythic spirit—an anima—spreading the sacred fire of inspiration, purification, and renewal? As I was viewing Fire Starter, an old cautionary song by T Bone Burnett played in my head:

Your captor is your comfort

You’re tyrannized by credit cards

You better keep your mind open

For the spark in the dark

Sparks are nothing if not shards of radiance. And radiance is another name for glory—and the domain of the sacred. Simcoe’s Black Drawings variously manifest glory in ways both sublime and subtle. In a recent conversation, veteran curator and art writer David S. Rubin told me he felt that Simcoe’s Black Drawings echoed Beat poet Allen Ginsberg’s epic masterwork Howl. A Buddhist, Ginsburg concluded Howl with a repetitive mantra of ecstatic proclamations: “Holy! Holy! Holy! The world is holy! The soul is holy! … Everything is holy! everybody’s holy! everywhere is holy! everyday is in eternity! Everyman’s an angel!”

Such supercharged sentiments are evident in Simcoe’s Candelabra, a monumental painting exceeding six feet. Here Simcoe has returned to his desert theme. Centered in nocturnal darkness, a single Joshua tree is supernaturally illuminated among a scattering of yucca palms. Above the tree a bright cluster of streaks rockets heavenward like a chorus of fireworks. Simcoe’s Eastern Orthodox faith affirms that creation has a divinely ordained integrity in and of itself by virtue of being created by God, and that all of creation is always praising God and working together with God’s purposes. Candelabra becomes a contemporary icon of this idea, bridging Christian tradition and the artist’s environmental advocacy. Indeed, Orthodox theologians contend that men and women have a priestly role as stewards of God’s creation, because the created world is a sacrament of God’s presence.

This theological truth is not restricted to nature alone; God does not care for wilderness or rural areas at the expense of cities, towns, and—yes—suburbs. In his Black Drawings, Simcoe labors to locate the specificity of mystery and revelation wherever they can be discerned: urban streets, residential suburbs, the skies of air travel, or the desert wilderness. For him the world is not merely a brute objective fact, but a mystery that, if probed, will richly disclose the deeper meaning that resides only in myth or metaphor. In this light, the world is semi-transparent. But seeing through it takes eyes and minds willing to look at and into the blackness.

Gordon Fuglie is an independent curator, art historian, and critic. He has worked at the J. Paul Getty Museum, UCLA’s Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Loyola Marymount University’s Laband Art Gallery, and the San Luis Obispo Art Center. His most recent publication is The Road to San Simeon: Julia Morgan, Visionary Architect of the California Renaissance (Rizzoli New York).