Jocelyn Mathewes is an interdisciplinary mixed-media artist whose work has been exhibited in galleries, museums, and community spaces all over the US. She has participated in residencies with the Artist Residency in Motherhood, Makers Circle, and Stay Home Gallery. In 2020, she founded EAT/ART space, an alternative pop-up gallery. She organizes artist meetups in the southeastern US highlands to foster regional growth, collaboration, and innovation. www.jocelynmathewes.art

Image: I’d like to talk about how your artistic and faith journeys intertwine. Can you speak first about your religious background?

JM: Growing up in New England, we attended a Baptist church for a time, then an evangelical Protestant church. We were devout; our faith was central to how we structured our lives. Worship was a mixture of traditional hymns and contemporary music, and preaching was heavily emphasized.

My parents were eager to educate me on the history of the faith. We studied Reformation history and theologies of other denominations, as well as some comparative religion. We discussed the Protestant rejection of images in worship, among many other controversies.

I was homeschooled by my mother, who was an artist in her own right. She studied painting at Boston University and taught lessons out of our home, so I had an example of artistic exploration and religious practice to follow and admire.

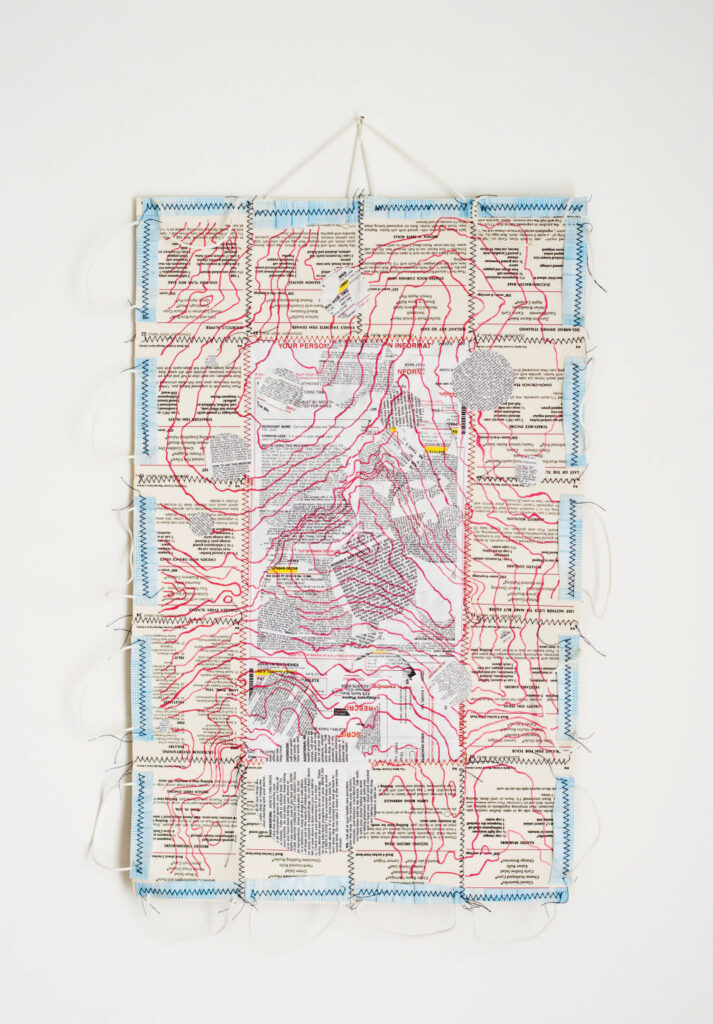

Jocelyn Mathewes. My Everest, 2020. Vintage recipe cards, embroidery, prescription sheets, medical masks, and ink. 30 x 16 inches.

Image: What do the rhythms of your life look like now, married to an Orthodox priest?

JM: I made the transition away from iconoclastic traditions when I encountered Orthodoxy in college and began to study art. Because artists think about the meaning of materials, I was naturally drawn to worship that made the material experience of worship into a feast.

When you are married to the priest, you are enmeshed in the life of the church. An Orthodox priest’s vocation is all-encompassing and involves the whole family. We shape our lives—meals, school, vacations—around the liturgical rhythm of the church. It’s intense and demanding, but the time we carve out for spiritual practice and contemplation is an anchor. My art practice flows out of the rhythm of faith, so I plan my time and husband my energy in response to and in support of these rhythms.

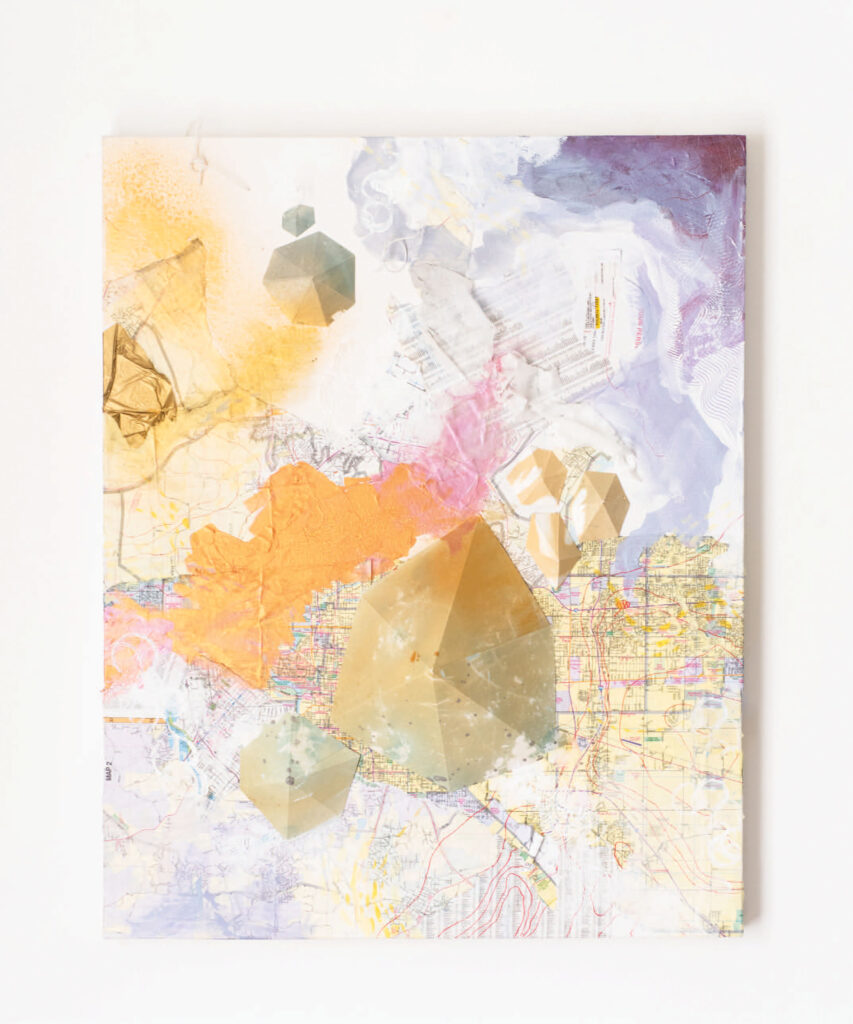

Jocelyn Mathewes. Do I Want to Be Made Well? from the series Sickness Is a Place, 2022. Cyanotype, prescription sheets, acrylic, and mixed media on canvas. 30 x 24 inches.

Image: Would you go as far as to say there’s a liturgical character to your practice as an artist?

JM: The heartbeat and steps of my artistic process are just as liturgical as my prayer life. Repetition figures both in medium and in execution. I work in printmaking and photography, which are mechanical and slow, repetitive. Each one has its own particular series of steps at which you can add variation.

My art practice also ebbs and flows like the liturgical seasons. Here in Appalachia, we have four seasons. During the summer I spend my time making cyanotype prints; it’s fastest and easiest when the sun and its UV rays are most intense. During the winter it’s harder for me to be outside because of some medical symptoms that flare in the cold. So I stay indoors and work the prints into shapes or focus on different media. Ecclesiastes 3 comes to mind. “A time to print and a time to sew.”

Image: Are there spiritually significant themes or imagery that recur in the work itself?

JM: Medical themes play a huge role—diagrams, organs, body parts, measuring tools, et cetera. Medicine has its own language and insights that feel very disconnected from the spiritual world, yet modern medical systems have played a large role in my healing from a chronic illness. I explore the gap between living in a body and the scientific analysis of bodies. In that gap I see faith create a deeper, integrative meaning, one that allows true and full healing.

Mapmaking is the second big theme—topography, cartography, and 3D elements. The three-dimensional structures I create are made from cyanotype prints that come from weeding my garden. The weed prints document the invisible labor of maintenance that goes along with healing from illness. All these methods try to describe and document that gap between medicine and faith.

Jocelyn Mathewes. After the Stroke, 2017. Gum bichromate, metal leaf, embroidery, medical bracelets, glitter, and hair on watercolor paper. 9 x 12 inches.

Image: Could you say a bit more about the images—or even icons—through which you explore ideas of healing?

JM: By its nature, my illness is invisible (as are many others). In one sense, my work is an effort to trace the outlines of my suffering, since it has no single, monolithic cause. I am navigating around it and through it, constructing the map as I go; that is why in my work you will find maps of recognizable places torn and mismatched—it’s no world that anyone knows.

So I outline it with the medical detritus that collects around me—paperwork, pill bottles, medical records, my own personal notes on my day-to-day symptoms. The gold leaf in my work is a way to sanctify those images. Turning these scraps into something beautiful is a metaphor for and a record of survival, as well as a description of the experience itself. In that sense, they’re an icon of illness.

Image: During the periods when you felt intense, ongoing physical pain, what kinds of artwork, if any, were you able to produce?

JM: Many kinds of art were possible, but I leaned on what was accessible given my physical state and my role as a caregiver.

I worked small and light, generally in two dimensions on paper, since pain makes it hard to wield heavy tools and objects. I worked out of my house using materials on hand, because it’s hard to leave the place where you’ve shaped your environment to better care for yourself. I leaned into the photography tools I had collected for my professional work, because that documented parts of my experience for contemplation and material.

The most glaring limitation was the pace at which I could work. I planned my time so that what I hoped to accomplish in the studio would fold into my overall energy requirements for a given day. I had to break the work into very small stages; this meant I often made multiples of a single image, so I could ride a wave of energy and work on them all simultaneously with different experiments or approaches.

Image: Some people describe chronic pain as a sort of hermetic universe, where it’s hard to think of anything else when it’s going on, but also challenging to inhabit and recall when you’re not in it. As you’ve healed, do you find yourself returning to those experiences in your work, or moving away from them?

JM: The functioning of our bodies affects what is possible for each of us in physical and temporal spaces. During active illness, the limitation that comes from the mismatch between the rest of the world and the universe of sickness increases. You think and plan around the ways you don’t fit into the world.

I haven’t been in remission for very long compared to how long I’ve been sick; my ongoing sense is one of awe and gratitude for what I’m able to do, as well as of otherworldliness. I’ve spent a lot of time experiencing an awakening sense of possibility, while at the same time wishing I could have felt that way during my active illness. What I know now is that the shape of possibility changes between the two states, but not the number of possibilities.

I find myself creating repeating forms. It’s a way to move through the ongoing sense of grief and loss—lost time, lost ability, lost pasts, and lost potential futures. Moment by moment I repeat the grief of illness, coming to acceptance and the presence of God, and then moving to gratitude.

Image: You mentioned maps as a recurring theme in your work. Could you speak about why they resonate with you?

JM: I have strong early memories of maps; my father enjoyed the niche sport of orienteering and took us to orienteering meets as a family in parks and mountains around the northeastern US. Now I live in the mountains of east Tennessee—the same mountains, just further south, and a formidable wilderness. Tenacious and resourceful peoples have made a life here for ages upon ages. I learned to navigate with a map and a compass in my youth, and here I am, in a new and somehow familiar wilderness.

Image: What role do you see for experimental artists in rural communities today?

JM: Experimental artists are ideally positioned to help activate a thriving culture in rural communities. Artists often see possibility and opportunity where others may not, so our role is to lead others into new ideas or ways of doing things. Artists also bring new and unexpected stories to the forefront, breaking tired stereotypes.

This is especially true for Appalachia, whose cultural representation is often less than flattering and overlooks the complex stories of the region’s people. Elements of Appalachian culture are being lost because certain stereotypes have made it shameful to celebrate them. The region’s artists have the ability and responsibility to share Appalachia’s true stories in ways that show its beauty, strength, and ingenuity.