Kylee Snow is a figurative artist working primarily in graphite. Her current body of work takes inspiration from old New England homes, exploring the deep relationships between home and inhabitants. Originally from Vermont, she is based in Brooklyn and completed her MFA at the New York Academy of Art.

Image: What is it about graphite that compels you?

KS: I love graphite’s simplicity and reflectivity. People often minimize its reflective quality, but I love how dramatically it interacts with light so a piece never looks the same. Graphite also mirrors a narrative ambiguity I try to bring to the work. The effort to grasp the image ties to the effort to grasp its meaning. Graphite’s lack of material complexity also feels honest. Since it’s a simple form of carbon, any mystery in a graphite work is created through process, and that feels like starting from a place of truth.

Kylee Snow. One and the Same, 2022. Graphite on gessoed board. 4 x 4 inches.

Image: People often think of drawing as a preparatory process rather than a culmination in itself. How do you play with or subvert that expectation?

KS: I’ve been drawing since childhood, and years ago I decided I would go as deep into details as I could, like I was a microscope. It was fascinating to realize there is always more texture and value, and to learn to connect the detail to the full narrative. While I have moved toward combining direct observation with more imagined elements, I find that my self-taught and somewhat obsessive practice of deep noticing remains an undercurrent in my work. I like to know as much as I can about one specific thing. There’s power in continually realizing that there is always more to learn. I enjoy pushing a medium often used simply into a more complicated space.

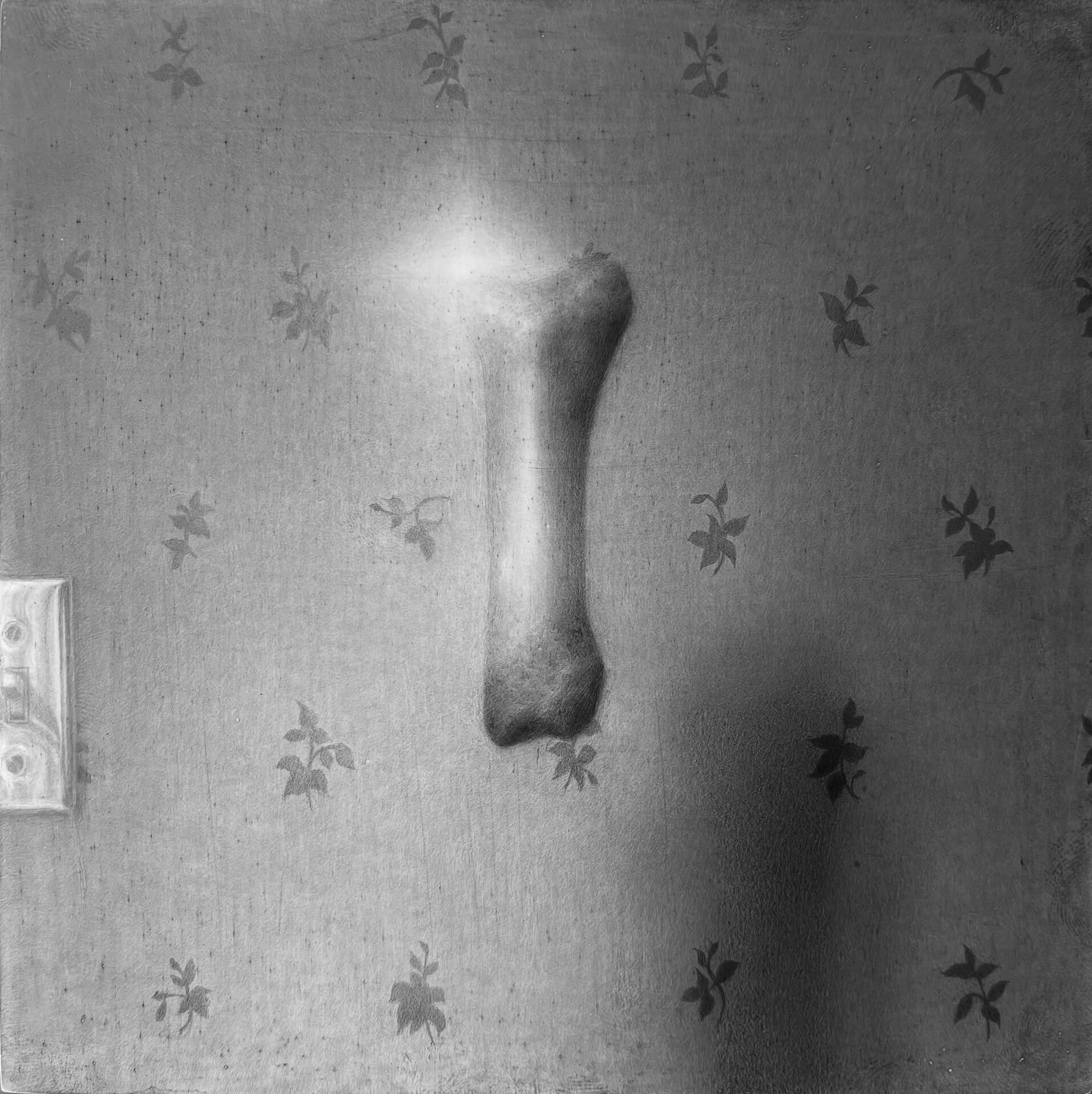

Kylee Snow. Good Bones, 2022. Graphite on gessoed board. 6 x 6 inches.

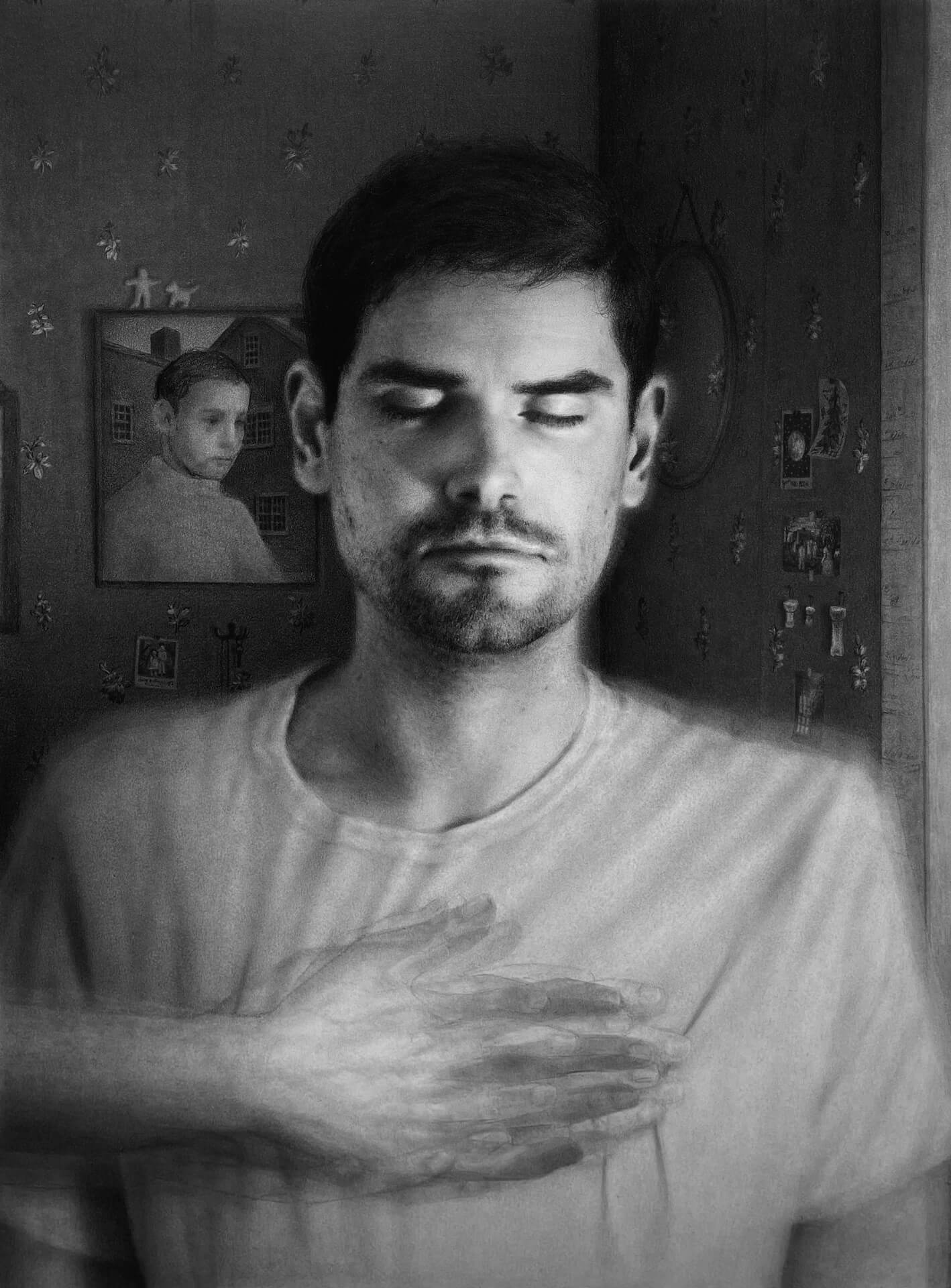

Kylee Snow. Little Airs, 2021. Graphite on Claybord. 12 x 9 inches.

Image: Paul Gauguin wrote in his diaries that his drawings contained his secrets. I think of that when looking at many of your works. Is the sense of secrecy or hiddenness important in your work?

KS: I’m currently exploring how we live in communication with built space, specifically the homes we know intimately. I’m interested in how we interact with and transform our homes to be ours and how that built space forms us in return. I’m also thinking about the home as a being itself, how it envelops the accumulation of small changes over time and lives on its own timeline as inhabitants pass through it. My recent work all takes place in and around the same imagined home. I feel like I’m building it and its history piece by piece. The work encompasses my own secrets when I pull details from my homes and possessions, and the unknown secrets of others when I find inspiration from historical homes and objects.

As I think about our complex relationships with our spaces, I’ve been envisioning bones as a static symbol of a life. Every bone is the remainder of a being and contains a lifetime of secrets. I keep thinking of the phrase “good bones” in relation to parallels between homes and our own bodies. Bones are our inner structure, supporting us as we make our homes our own and live within their built skeletons. Each skeletal system supports the other, and both contain multitudes of secrets.

Image: Another strong feeling I get when I spend time with your work is uncanniness. How do you evoke the uncanny without just getting straightforwardly spooky?

KS: I am always trying to walk a line between telling too much and too little. Spooky is obvious and overt, built on clear and recognizable cultural symbols and evoking specific feelings. Uncanny is sneaky—using and subverting symbols to evoke feelings that are harder to define. I have my own thoughts, stories, and feelings that go into the work, but I never want those to be obvious. I want to connect to something universal through subjects that elicit others’ feelings and draw on their personal histories and secrets. Graphite is quiet, and I try to be subtle but with some underlying, often uncanny disquiet.

Kylee Snow. It Holds, It Pulls, 2022. Graphite on paper. 18 x 13½ inches.

Image: Are there specific places and histories you’ve used for inspiration, or do you work more from the imagination?

KS: I have a long ancestral history in New England and strong ties to the home in Vermont where I grew up. The imagined home I am constructing is an amalgamation of historical New England homes, personal and familial histories, and imagined content and compositions. I am also inspired by literature and currently thinking a lot about Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space.

Image: Many of your works involve “ghost images,” conjuring a palimpsest in which previous images seem to hover and evade full erasure. How do you achieve this effect technically, and what does it signify to you?

KS: As I’ve been focusing on relationships with physical homes, I’ve also been thinking a lot about perceptions of time. We all exist within the rules of this extremely personal, indescribable thing that makes everything what it is and dictates everything we know and experience. Everything we interact with has its own timeline, separate from but intersecting with ours, and on some level must have its own perception of time. The palimpsest is a strategy to explore how an old home might experience time. For example, I built Organic Habits from imagination, beginning with the solid, immovable physicality of the house itself, then adding furniture and decoration, overlapping and changing, then finally traces of people, envisioned as patterns in which the home might guide them over time.

Kylee Snow. Organic Habits, 2022. Graphite on paper. 25 x 38 inches.

Image: Recently you seem to be homing in on specific objects more than scenes. Do you think of these objects as bearing an aura or a sense of the sacred?

KS: Objects can have deep known or unknown histories. They interact with the homes they occupy and hold meaning for each person they belong to. I like to think that, like bones, they can carry hidden memories, connections, and secrets in their materiality. I think of these household objects as bearing their own auras accumulated over years of use. They live with and beyond us in a complicated web of movement and time, bearing witness to and participating in life.