Stephanie Rayner is a multimedia artist and international lecturer whose work engages with the transformation of spirituality by science and technology. Born in Toronto, she spent ten years traveling the globe overland before beginning her art career in 1982. She has lectured at the Vatican Symposium on Religion and Science (Malta), the First International Symposium of Religion and Science (University of Toronto), Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study, and multiple art institutes in China. She is the only visual artist ever to be awarded the Ashley Fellowship by Trent University.

Image: Could you describe the moment when you knew you would become an artist? Would it be fair to call it epiphanic?

Stephanie Rayner: I take the word artist very seriously. I am not an artist until that flame within me is lit. So, the beginning of, and the commitment to, each major artwork contains that moment. I need to continually become an artist, to reimagine myself. I let imagination nourish the mysterious becomings within the soul.

But, yes, there was one particular moment. I was young enough to be carried in the crook of my father’s arm. At dusk, all of a sudden, a tree on the far side of the garden glows gold. Through my eyes I am pierced by beauty. I crumple forward.

Stephanie Rayner. Angel Dancing on the Head of a Pin (detail). All photos: Rob Davidson.

Image: You’ve spoken about how your travels around the world became a springboard for your art. Could you talk a bit about some of the more spiritually compelling experiences on these adventures?

SR: My travels began before cell phones and computers. If you had the will, there was a way to go back in time. If you could ride a horse, if you could tough it out, you could visit remote places with ancient energies, energies not of the twentieth century. For fifteen years, I traveled paths less taken: temples entangled by jungles, mountain shrines, deserts. In these places, sometimes, the veils do lift.

On a trip overland across North Africa, I rode across part of the Sahara starting at Giza. Sitting on my horse, quiet and alone between the giant paws of the Sphinx, my vision was fixed on the horizon point where those unblinking eyes had been focused so fiercely for millennia. Then I heard a chunk, chunk, chunk. I moved the horse from between the huge paws to see (hooves in sand make no sound). A young man and woman were digging a grave beside the Sphinx for a tiny, tightly shrouded baby. The juxtaposition between that powerful, timeless, indifferent stare and the poignant measure of that moment is bound to the core of my being.

Stephanie Rayner. Angel Dancing on the Head of a Pin. Wooden pulpit, welded cross, etched artillery shell, glass chambered needle, wishbone, vertebra, eggs, raven wings, shadow. 9 x 2¼ x 3¼ feet.

Image: You use highly unusual materials in your work, from raven’s wings to an artillery shell, vertebrae, maps, and even DNA sequencing gels. Do you find yourself saving objects and then finding uses for them, or rather thinking of what a specific work needs and then searching for the right objects?

SR: Some materials find me; others I search for. The materials for Angel Dancing on the Head of a Pin took me to an illegal arms fair. Later, I had to carry a rectangular clear plastic package of white powder—dental amalgam—through a drug gang area of Toronto, with no purse or pocket to hide it in. It took five years to find a truck-smacked raven (it’s illegal to deliberately kill ravens in Canada, so I needed one that was already dead), and then I had to finger-lick all the barbules back together on both wings. Other materials just fell into my hands.

Image: Are there objects that have felt too sacred to use in your work? Or objects that suddenly seemed to become sacred when you placed them within a work?

SR: Ah, what adventures we will miss in not telling of the procuring of profane materials!

Of the sacred there have only been two. In my work Dialogue of the Two Chief World Systems—which takes its title from Galileo’s radical tome—there is a rusting 14-carat-gold-leafed birdcage. It has church doors at each end. Within the birdcage is a gold cross on which there is a wasp’s nest the size of a human head. The paper of the wasp’s nest is made of chewed-up pages from the New Testament. I could not tear up the Bible I owned. It is the kind of Bible with gossamer pages, all gilt edged. To do the tearing I had to (and the irony here is not lost on me) steal a Gideon Bible from a hotel room bedside drawer.

The other sacred object is a graph printout of a dying human heart. You can see the path of that heart’s struggle up the mountains of that graph only to flutter, fail, fall, and then struggle up again. There are handwritten notes at intervals done by the attendant—for example, “the patient blinked.” I am not sure yet if or how I will use the map of this journey in a work of art. It was to be paired with NASA’s pulsar radio signals that sound like a heartbeat from the universe. I hold it in keeping with great reverence and tenderness. My eyes tear up each time I look at the end.

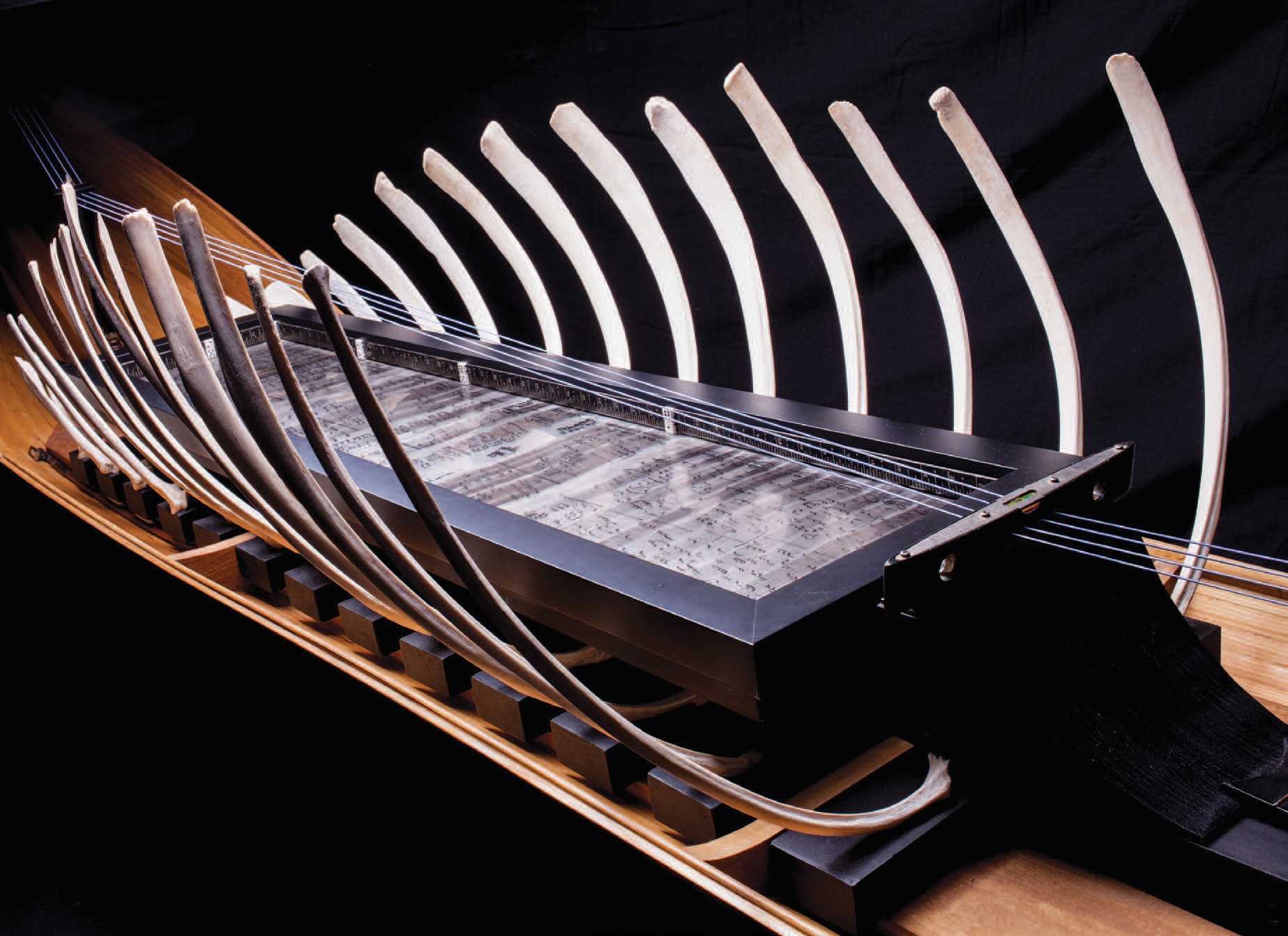

Stephanie Rayner. Boat of Eternal Return, 1998–2012.

Pine, tulip poplar, mahogany, ebony, moose ribs, guanaco coccyx, mare pelvis, ruler, dice, DNA sequencing gels from the Human Genome Project, score of Mozart’s Requiem, cello components, hand-worked glass, spirit level. 9 x 30 x 2¼ feet.

The work also includes a long poem braiding childhood memories, dream images, scenes from Rayner’s travels, and elements from her research. Its full text is at her website.

And if all things come into the world bringing

the balance of their opposite, is it then the same boat

now returning from its dark crossing,

moving like a loom’s shuttle between opposite shores

that weaves with its recurring rippled wave a matrix for art?—from “Boat of Eternal Return”

Image: Last year I had the privilege of talking with you in front of your Boat of Eternal Return. How have people responded to that work, especially spiritually?

SR: There is a silk scarf that travels with the boat. Four Buddhist nuns traveled from the residence of the Dalai Lama in Dharamshala, India, to see the Boat of Eternal Return in a Toronto art museum. They walked around it four times chanting, then knelt beside it and prayed for the boat to bless them. Then they sang prayers standing in front of the high prow, and at the end of that hymn, Maio Lin draped the keel with the silk scarf to bless the boat on its long journey.

There is a book that travels with the boat, in which people write comments about their experiences with it. After reading it, as one curator said, “People don’t just write their names; they pour out their souls in essays!” One viewer wrote, “You have looked into the eyes of my soul and played the strings of my heart.” Another wrote, “I know one day I will float in the embrace of those ribs of the boat. But now when that boat comes, I will not be afraid. How graceful and deep this Peace Inconceivable.” Another called the boat “a gondola on which spiritual seekers, shamans, and mystics can move to the spirit world without the normal requirement of death.”

Boat of Eternal Return details above. Between the moose ribs is a copy of Mozart’s original score of the Requiem, transcribed onto DNA sequencing gels from the Human Genome Project.

Boat of Eternal Return details above. Inside the prow, the cello strings pass through the birth canal of a mare’s pelvis.

Image: In many of your works, research plays a strong role, and you’re often in touch with leading scientists in experimental fields from genetic research to astrophysics. What have you learned from these encounters, not just scientifically but perhaps spiritually or artistically?

SR: I have been deeply inspired by scientific discussions and projects I was allowed access to, and in return I found scientists who were enthralled and moved by seeing their work transformed into visual poetry by the power of metaphor. I think of the great generosity of spirit and respect from people like Dr. Chris Corbally, a Jesuit and former director of the Vatican Observatory Research Group, and Dr. Alan Davidson of the University of Toronto, who worked on the Human Genome Project and was recently part of the team developing the gene-editing technology called CRISPR.

I’ve learned that art, science, and religion are still fueled by ancient desires for a dialogue inherent in the mystery and magic of creation and destruction. And, as many myths reveal, we have an abiding desire to steal a portion of that power.

Once you explore the revelations of science—the multiverse, black holes, dark matter, quantum physics, the photographs of far galaxies sent back by the James Webb telescope—there is a realization that in our era humankind is experiencing the birth of a profound new consciousness. All births are painful and contain elements of danger and risk, but births are the necessary threshold for evolving potential.

In some cases, my work deals with the perceived pitfalls of the Trickster’s gift of technology, while other works, I believe, disclose the possibility of a bridge between science and spirituality, a bridge not based on any one culture’s interpretation of god, but rather the sacred as revealed through universal phenomena that bind us to the cosmos.

And as to our ancient desire for that dialogue, we now use hugely powerful artificial eyes and ears to slowly scan the heavens, waiting for a sign.

In a January, twenty years ago, I was taken to the necropolis pit

in a wilderness park

There, out of the crystalline snow, arched great racks of ribs—red

with ragged flags of flesh drooping between the white of bone

Black trees ringed the pit

tall and massed with ravens as thick on the limbs

as leaves—from “Boat of Eternal Return”