THE STORY GOES LIKE THIS:

A long time ago, the raven looked down from the sky and saw that the people of the world were living in darkness. The ball of light was kept hidden by a selfish old chief. So the raven turned itself into a spruce needle and floated on the river where the chief’s daughter came for water. She drank the spruce needle. She became pregnant and gave birth to a boy which was the raven in disguise. The baby cried and cried until the chief gave him the ball of light to play with. As soon as he had the light, the raven turned back into himself and carried the light into the sky. From then on, we no longer lived in darkness.

In many ways it really is the first story, a redemption narrative that also includes creation, incarnation, transubstantiation, and apocalypse, but it’s also the first version I heard of a story I would hear again many times.

The trickster-raven cycle is a kind of ur-story for tribes native to the Pacific Northwest, as ubiquitous among those groups as Noah’s ark is among some others. I first encountered it in junior high after my family moved to Washington State. It has traveled well beyond those bounds too, wandering in and out of other stories like some curious bird.

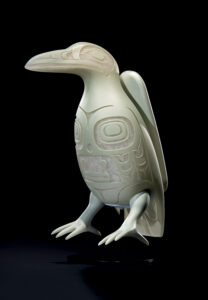

Preston Singletary. White Raven, 2018. Blown and sand-carved glass. 18½ x 7 x 9 inches. Collection of the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

In poems, every word matters. In holy Scripture, the Word is what matters. But here, though the language and idiom may change with time and taste, the cycle is what matters. Being a myth, the raven story can change its contours with each telling, but so long as certain events take place, it remains the raven cycle. It is still itself, you might say, in whatever form it takes.

At the Tacoma Museum of Glass, when I saw Preston Singletary’s Raven and the Box of Daylight, a show that has since traveled to the National Museum of the American Indian and earned heaps of praise from critics, the feeling I had was of what E.T.A. Hoffmann would have called the uncanny: the familiar in the strange, or the strange in the familiar. It’s what we feel when looking at a stranger we think we recognize or hearing a remixed version of a song long cherished. I walked through the show enraptured, but with a constant nagging sense of déjà vu.

Preston Singletary. Raven and the Box of Daylight, 2017. Lead crystal. 32¾ x 9¾ x 6 inches. Photo: Russell Johnson.

It wasn’t that the raven cycle so beautifully maps onto the Christian story of self-sacrifice and redemption-a mapping that is not, I think, a matter of cultural appropriation so much as of two cultures working toward and finding the same truth about the structure of the universe and the human heart. Rather, between those glass monoliths, the words of the familiar raven story were there, and they were different. Singletary had taken a story I’d cherished for twenty-some years, one that I’d memorized, and made it fresh.

Where I had “the chief’s daughter drank the spruce needle that was Raven in disguise,” the text accompanying the show, which is printed and sometimes projected on the walls, reads, “Yeil is ingested by Naas Shaak Aank-áawu du Séek’ and she becomes pregnant with Yeil,” with all proper names rendered in Tlingit.

I still remember the first time I read the Bible in French. When I read about these guys following Jesus called “Pierre, Jean, and Jacques,” I just couldn’t get over it. The names sounded too contemporary, ridiculous even. Of course, I realize that no one in first-century Nazareth was calling out “Gee-zuss” either, but on some linguistic level, I couldn’t hear it at first, wrapped in that new idiom. And when I did, my understanding of the Gospels changed. The flannelgraph cutouts took on flesh, became as real as rocks. Maybe as a poet I obsess over the particularity of words. Maybe speaking only European languages has limited my imagination.

In any case, Singletary’s gesture of giving these characters back their original proper names puts them back into the culture from which they sprang. Out of the ether, out of folk mythology, out of the translated and imperialist past they go, into new and radiant life. Like Raven bringing the revealing sun, this show took what was in darkness-that these myths, whatever they mean for the world at large, belong to a particular people with a particular past, who speak a particular language-and brought it to light.

Preston Singletary. Indian Curio Shelf, 2008. Blown and sand-carved glass on paper stone shelf. 10 x 52 x 14 inches overall. Photo: Russell Johnson.

To arrive at the translation the show uses, Singletary worked from a text by a Tlingit clan leader named Austin Hammond, who told the story in the original language. There’s an important concept here called att owoo. In his culture’s understanding, stories don’t exist as texts that anyone can just use. They’re proprietary to a certain tribe, to certain clans within that tribe, even to certain families within the clan. The story belongs to someone who is given the permission, the responsibility, to tell it. That person is the story’s caretaker until such time as it can be passed on to another teller. So Hammond performed the raven story, and then Singletary, along with curator Miranda Belarde-Lewis, distilled the five other extant versions into the written guides that accompany the glassworks.

Raven and the Box of Daylight is more immersive than many museum shows in that a series of interrelated objects work together to create a totalizing experience that is almost theatrical, a Gesamtkunstwerk. As the visitor confronts images in a particular order, they all string together to tell a story featuring individual characters. There’s video projection, sound installation, and large- and small-scale glass objects. There’s a box made of glass panels containing the sun as well as various tools-rattles, combs, fishhooks, all made of mixed-media and glass-to help establish the world in which this story was birthed. There are life-sized figures carved from cedar with blown-glass heads and hats, wearing traditional regalia. It’s a piece of theater and a whole museum’s worth of objects in half a dozen media that together peel back the lid of the dark box.

For several weeks, I couldn’t stop thinking about it, so I asked his gallerist if Singletary would be open to meeting. Over lunch near his studio in Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood, I asked him about the process of putting together this show. Did he consider it his masterwork? “Well, how often are these opportunities going to come around?” he said. “Honestly, I don’t know if I could make another show of that magnitude, if only because it was so much effort. I was at a liquid phase in my career.”

Later at his studio we got to talking about his background. He’s a person of two cultures, he says. Born of a broadly European father and a Tlingit and Filipina mother, he grew up in urban Seattle. At Pilchuck Glass School, he began studying what was then a burgeoning medium. He learned glass blowing and developed a deep respect for European traditions of art making, going on to study Venetian glass techniques with an Italian master, while also working with members of neighboring tribes on both art and activism (and playing in an indigenous music band called Khu.éex’). All this boundary-crossing has set him up to occupy a unique space in the art world. He can dive into the deep streams of Native American mythology and imagery and, often using techniques born in Europe, can render the familiar strange and the far-off near.

Consider the totem pole, for instance. What began as a storytelling marker for particular Haida and Tlingit clans in what’s now British Columbia and Alaska came to stand in for Pacific Northwest tribes more generally, and even for Native American storytelling itself (think totems along Route 66 in Arizona). Though historically the Seattle-area tribes never made them, they’re everywhere here. There’s one outside my office window at Seattle Pacific University, a gift from a local tribe in thanks for the university’s decades-long support of Native culture, particularly in offering theological training for Native pastors.

The thing about totem poles, though, is that they’re displayed outside, where the wind and weather wear them down over years. That makes these iconic representations of Native identity fragile, even when they’re made from half a ton of solid spruce.

That has its beauty too, of course. Like theater or feasting, it is worthwhile and meaningful to make something that won’t be around forever. But as anyone who studies Native cultures can tell you, it would be nice if some cultural artifacts were more enduring. Long-lived artifacts ensure a culture’s survival, in a way, at least inasmuch as something as complex as a culture can fit into an artifact. But isn’t that what we believe art is? A kind of window through which it is possible to glimpse an enormity?

What’s supposed to have happened is this: as with the stories and dances, every generation is tasked with finding suitable caretakers for the culture’s artistic productions. A wood totem left out in the rain will last around seventy years, an average human lifespan, before it will need to be re-carved. The system leaves everyone with work to do: the older generation must train the next; the younger generation must agree to carry the tribe’s stories forward and to train their young in turn. It’s a beautiful, holistic, communitarian structure that works well, until something like a smallpox epidemic arrives, such as the one that hit Alaska in 1835, taking 70 percent of the Native population in some areas and wiping out entire villages. Huge swathes of custom and craft are lost. If thereafter, among those who remain, Native art-making is suppressed by well-meaning missionaries who teach against the making of “idols,” well, it’s cultural Armageddon.

Again, Singletary introduces a small change that is enormously significant. He shifts the medium. Using traditional tribal motifs and visual vocabulary, he carves totems out of bronze, one of the most durable substances known to man. The implications clang and resound. For one, age: here’s a totem that, unadulterated, won’t fade like so many other tribal productions. For another: weight. Wood totems are not exactly convenient to transport, but they can be carried by a group of people for hand installation. The sheer mass of Singletary’s totems makes them monoliths, so attached by gravity to a particular place on earth that they may as well be rooted. Yet one more implication: size. Because their density conveys the heft and force usually achieved by dramatic height, some of these bronze totems can stand only three or four feet high and achieve the same effect. As with all great art, these translations challenge what, in effect, the thing actually is. What’s a totem that isn’t made of wood? What’s a totem that can fit in one’s hands? What if it isn’t even columnar?

Recently, Singletary has been carving totems from lead crystal: a trick that has amazed every glass worker I know. Apparently, this should be impossible. I should have put “carves” in scare quotes, because one doesn’t carve bronze, much less glass. Instead, Singletary uses the most advanced glass sculpture techniques from around the world; he uses a good deal of physics in calculating, for instance, how much weight a lead crystal base can be made to bear; he uses a good deal of money for materials and shipping. With a team of assistants from across the globe, he transforms what was one sort of object-the kind we might take for granted, might drive right past-and makes it the sort of thing that elicits gasps. Technically, they’re carved from wood, sent to the Czech Republic to undergo a lost wax casting process whereby plaster molds created from the negative space are injected with glass chunks in the open form. The glass is then melted very slowly, the plaster broken away, and finally the surface unified with cold-working techniques, before they are shipped back across the ocean.

Preston Singletary. Killer Whale Totem, 2022. Lead crystal. 106 x 33½ x 22 inches. Shown at Seattle Art Fair, currently on view at Blue Rain Gallery. Photo: Russell Johnson.

The change in medium from wood to glass-for the totems, the hats, the clan house-means something else too. The first thing most people think of when they think of glass is that it’s fragile. And that is the truest thing that can be said about cultures generally and about Native American cultures particularly. They’re so beautiful and so often broken. Another thing about glass, though: it’s luminous. There’s something strange and perfect, uncanny, even holy, about being able to see light through what was once dense and obscure. Singletary takes all the history and groundedness, the reverence and vocabulary of these objects, and adds luminosity. Everything is familiar here-there’s the eagle; there are the ovoid eyes, yes; there’s the height and weight-but it’s glowing from inside. The glass totem bears meaning as easily as the river bears a spruce needle, but it’s bathed in radiance as if the spruce needle is really the sun.

Again and again, Singletary displaces the viewer by transforming traditional crafts and folkways into new, light-bearing idioms. Take Wolf Hat (1989) for instance. It’s a hat, such as coastal people would once have worn around here to keep the rain off, likely wound from cedar bark, but sitting upturned on a table, it’s more like a fruit bowl. That’s one transformation. Singletary also renders the Tlingit ceremonial accessory in blown glass. That’s another. A glass hat is useless, of course, which is part of the point. What was once functional is now, like so many folk creations, from Austrian silver serving spoons to Japanese teacups, an art object. Perhaps that’s a third transformation. But that’s still not what Wolf Hat is. Properly displayed, a beam of light shines on the upturned-hat-cum-decorative-serving-bowl. The light shows obscurely through the etched portions and cleanly through the untreated areas, so that the hat acts as a kind of projector, the motif of two wolves facing one another playing out in light and shadow on the supporting pedestal. It’s a sculpture made of crystal and shadows. It’s fixed and narrative at once. It’s two-dimensional and three. It’s as ancient and modern as film: telling stories in the dark.

Preston Singletary. Crest Hat, 2021. Blown and sand-carved glass. 5½ x 21¾ x 21¾ inches. Photo: Russell Johnson.

The week after we talk, I return to Singletary’s Pioneer Square gallery to look again. I leaf through prints and linger in front of a bronze totem called Two Ravens. But the more time I spend with his work, the more I have come to appreciate his domestic pieces. It’s easy (and meet and right) to be impressed by the monumental works: the six-foot solid glass panels of Clan House (2008) for instance, showing the sprit beings responsible for holding up the sun and the moon, or the two-thousand-pound cast-bronze totem, or the multi-room, sixty-five-object Raven installation. But increasingly, I’m drawn to works like Kakwx (Baskets) (2016), a collection of blown-glass containers with traditional tribal patterns. Part of the allure is, like Wolf Hat, their very uselessness. No one is going place one of these baskets by the door to store mittens. Another part is the rescue mission. To make sure the patterning was authentic, Singletary combed photographic archives of early Western contact with his tribe. Still another part is the craft. At first glance, they appear woven, like any Native baskets one might find at a roadside reservation stand or tourist shop. But of course, glass doesn’t weave, which means that in addition to creating the broad decorative pattern, the artist has created a consistent textural pattern to mimic the hand-pulled heft of natural fibers. The process he calls “staged blasting” involves applying thin slitted vinyl tape to the surface of the vessel-so he weaves the whole basket, but in tape-then sandblasting, then removing layers of tape and repeating the process. And then there’s the light.

Here’s another one of those cases where mixing is a strength. Concrete was actually quite brittle until someone thought to add iron rebar. Most organisms survive at greater rates when their DNA is diversified. Access to varied foods increases longevity. Singletary’s blending of a thoroughly European way of making and a thoroughly non-European subject and aesthetic has made both things better. By casting the traditional in new mediums, by grounding his work in all the strength of his cultural line, believing there’s something in the old chief’s cedar box worth getting, his work changes things, illuminating the spruce, the woman, the child, the chief, the sky.

Mischa Willett is the author of The Elegy Beta (Mockingbird) and Phases (Cascade) and editor of Philip James Bailey’s Festus (Edinburgh). His poems, essays, translations, and academic articles appear in a wide range of venues. He teaches at Seattle Pacific University. www.mischawillett.com