Jake Lever is a British visual artist living and working in Birmingham in the United Kingdom. Here he reflects on the last thirteen years of his practice, examining his engagement with the archetypal image of the boat through a series of site-specific installations and participatory projects.

“One of the most calming and powerful actions you can do to intervene in a stormy world is to stand up and show your soul. Soul on deck shines like gold in dark times. The light of the soul throws sparks, can send up flares, builds signal fires, causes proper matters to catch fire. To display the lantern of soul in shadowy times like these-to be fierce and to show mercy toward others; both are acts of immense bravery and greatest necessity.”

-Clarissa Pinkola Estes

Ark, 2010.

Willow, tree branches, and gold leaf on recycled cardboard and rope. Installation in Hailes Church, Gloucestershire.

IN THE MONTHS FOLLOWING MY FATHER’S DEATH, I made a work called Ark that sprang from a deep, primal yearning to honor his passage to the next life. My father, Peter Lever, was from a naval family and had loved boats all his life, but this work was not consciously prompted by biography or memory. Created using willow and sticks sourced from a nearby wood, the fifteen-foot structure was made instinctively, a sculptural weaving that was both cradle and coffin. Not far from my studio was situated the tiny Norman church of Hailes, once a field chapel for pilgrims journeying to the holy shrine nearby within Hailes Priory. Thanks to an imaginative priest, I became the unofficial artist in residence, and over a period of four years the site hosted a series of events called “Pilgrimage to Hailes.” Other artists and performers were drawn in, and together we created installations and events for present-day pilgrims of all ages who camped at the fruit farm up the lane. The 2010 pilgrimage provided the context for installation of Ark, animating this medieval space with a contemporary intervention. I gilded recycled cardboard, attaching flexible “planks” to the willow frame. This extravagance felt significant, a gesture of abundance. The roof beams of the church’s intimate nave strongly evoked an upturned boat, and hanging the vessel from these rafters seemed a natural, complementary act. Something akin to a giant belly, cocoon, or womb, the form quietly asserted itself in this ancient sanctuary: an ark waiting to convey a precious soul to a life beyond.

Bardsey Boats, 2013.

Ink and gold leaf on driftwood from Bardsey Island, Wales. Edition of ten.

Collaboration with the Reverend Chris Thorpe.

In 2013 and 2014 I made several visits to Bardsey Island (Ynys Enlii) off the rugged coast of Wales. Sometimes known as the island of twenty thousand saints, it was a major pilgrimage site in medieval times, and a place where many went to prepare for death. Bardsey is now home to a handful of people who live without electricity, cell service, or Wi-Fi. It is what many would call a thin place, where the veil between this world and eternal reality appears imperceptible. Combing the shores, I collected driftwood, using it to create miniature sculptures small enough to fit into the palm of a hand. I drew simple, stylized boat forms onto these fragments, gilding them on the island. Because of my interest in participatory work, I decided to collaborate with Chris Thorpe, an Anglican priest and a seasoned Bardsey pilgrim. We agreed that he would give these works to people in his Shropshire parish who were journeying through the final stages of terminal illness. For many, the pieces served as catalysts for conversations with family and friends around death and dying. Sanded by ocean currents and illuminated in the deep stillness of the island, they served as transitional objects for the end of life, frequently entering the darkness of their owners’ coffins.

Hailes Boats, 2013.

Wire, tissue paper, and gold leaf.

These Hailes Boats were created to be shown as a miniature flotilla, a family of souls in communion with each other. Photographed on a stone window ledge in Hailes Church, this image has resonated with people at seminal moments in their lives, often at the crossing from life to death. Paper thin and lightweight, these gilded, preindustrial forms seem to combine opposites: empty seed pods suggestive of cycles of birth, death, and resurrection. The archetype of the boat captivated me back then, and thirteen years later it still preoccupies me, alongside wider sociocultural and political concerns. Refugees and asylum seekers attempting to cross the English Channel from France in small boats, often with tragic consequences, are the focus of current media reports and public debate in the UK. My art practice is not a detached, sentimental exercise. The association of the boat with death has powerful contemporary resonances for me, connected to ongoing economic injustice and our collective vulnerability in relation to rising sea levels and the impact of climate change.

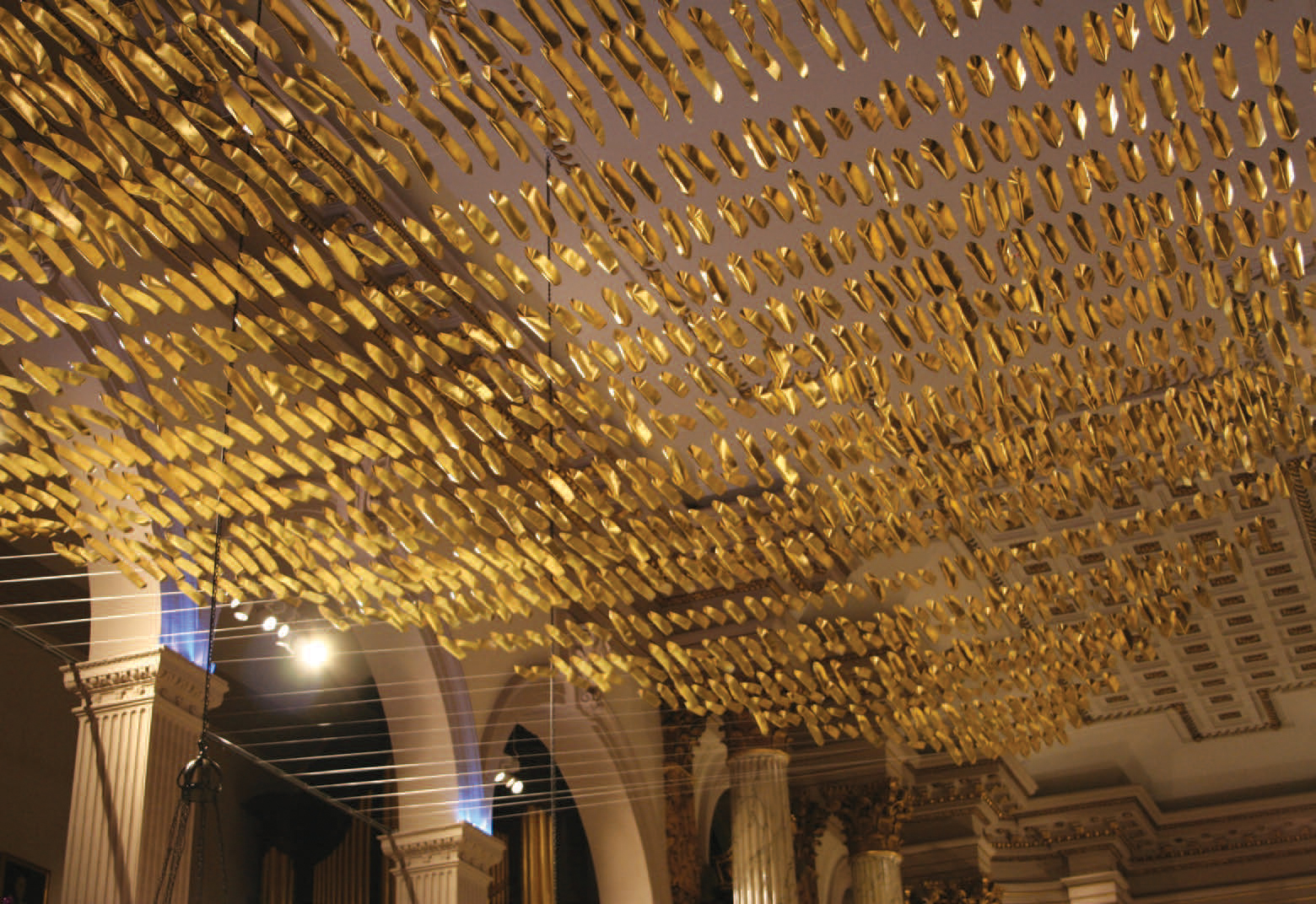

Soul Boats, 2015-16.

Installation in Birmingham Cathedral. Funded by the Westhill Endowment.

In 2015, the dean of Birmingham Cathedral invited me to create an installation to mark the cathedral’s tercentenary. Her hope was to “give the cathedral away” to the city, to celebrate the fact that this was everyone’s sacred space, regardless of faith background, in the heart of their city. I conceived the idea of a multitude of boats, a collection of vessels united in a single boat-shaped flotilla. I also suggested that we hang these boats in the nave, an ancient votive practice in the coastal churches of Europe. To ensure uniformity in scale and shape, a template was designed, with golden hulls and a hidden, interior space that invited children and adults to draw, paint, collage, or write personal memories, prayers, and reflections. Created in hospices, youth clubs, schools, sacred spaces, and scores of community settings across the city, boats were made in memory of loved ones who had died, as cries for help in finding employment, as prayers of thanksgiving and gratitude, for peace and justice. The privacy of the exercise released people. All two thousand boats were gathered and hung high above the nave, heading east toward the high altar in the sanctuary. The flotilla formed a gentle arc, recalling the underside of a ship. This constellation of souls held dualities together: fragile and confident, public and private, full of individual expression yet communal. For all its size, spanning the full length of the nave, it was also a simple intervention in this Baroque interior. Soul Boats provided a rare space for reflection, honoring diverse individual stories within a unified whole, framed by the public story of a much-loved cathedral.

Do the Little Things, 2020-21.

Wire, tissue paper, and gold leaf with cardboard box. Edition of 350.

In 2020, as lockdowns were enforced in the UK in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, I questioned how, as an artist, I could speak into this place of chaos, uncertainty, anxiety, and loss with compassion and integrity. I began to use jewelry wire to make the very smallest boats I possibly could-about five inches long-layering them with tissue paper and covering them with gold leaf. Placing them in small boxes, I started to send them by post to family and friends, as if to say, I cannot be with you in body, but I am with you in heart and spirit; we journey into the unknown together, and you are precious to me. Wishing to widen the reach of the project, I made more boats and offered them for purchase on my website, inviting people to pay what they could afford. By sending boats to their own loved ones, they could participate in a global project that sought to animate threads of human connection at a time when relationships were painfully compromised by social distancing and the limitations of screen-based communication. The project title, Do the Little Things, referred to the words of Saint David, who, on his deathbed in AD 589, urged his followers to “be joyful, keep the faith, and do the little things.” Boats were sent across the UK and the whole globe-in total 350 were made and sent to destinations from Melbourne to Myanmar, San Francisco to Santiago, Cairo to Cape Town. The stories behind their sending revealed a primal human need to mark sacramental and significant moments: to celebrate a friend’s breaking free from an abusive relationship, to console a relative upon the death of a baby, to honor a marriage on the other side of the world. One participant wrote, “I suppose the boats resonated with me as representing safe passage in times of transition-both joyful and traumatic. I sent them to friends as waymarkers at times of change when I couldn’t be physically present with them.” Her words are testimony to the possibility of art to facilitate authentic human connection, to enable us to be emotionally present to each other in real, honest ways; or, in the words of Clarissa Pinkola Estes, “to display the lantern of soul in shadowy times.”

Ark, in process.

Jake Lever is a British visual artist living and working in Birmingham. He is assistant professor at Warwick University and, with Gillian Lever, codirects Lever Arts (www.leverarts.org), an organization seeking to work soulfully with people, materials, and places.