WHEN I WAS YOUNG, we had a rickety old bureau at the top of the stairs. In the top drawer was a folder of family photos, loosely gathered. There was no album, no commemoration, nothing to mark them as precious. I would rifle through these snapshots frequently, looking for clues to my place in our family. I was fascinated by the way photos could place a person in a family context. My two brothers, five and ten years older, featured predominantly—reflecting the enthusiasm and hopefulness that often come with firstborn children, and that sometimes wane with each successive addition. There were few images of me. Although I wouldn’t have been able to articulate it then, this confirmed my feeling that my position in the family was unstable, fleeting, insubstantial.

My photographic work is in many ways a reaction to this feeling, as if I’m trying to create something fixed in a world where everything is ultimately temporary. Since its inception, photography has been associated with time and memory. In photos, past generations stare fixedly and stand stiffly before the lens, looking forward in time; from our end, we look back and try to understand what their lives were like. We peer into their eyes, trying to connect. The image seems to promise a bridge to the past, but it’s a false hope. The figures are immutably fixed in that moment of capture; we can’t really communicate.

There is a reason we talk about “capturing” or “taking” photographs. Many cultures have recognized and rebelled against this notion, believing that a photograph takes something away from its subject, perhaps part of the soul. In other words, that photography is a kind of theft.

There is something to this. A photograph, a supposed facsimile of its subject, claims a truthfulness that is really an illusion. The perspective and intention of the person taking (taking!) the photograph introduce an inevitable subjectivity.

And once an image is reproduced, digitally or in print, and goes out into the world, there is another separation. The photograph-as-artifact can be presented in entirely different contexts. It is open to misinterpretation, or to becoming fodder for narratives that have little to do with the original subject. Nowhere is this clearer than in the brave new world of AI, where images can be instantly altered, manipulated, and used to spur whole new interpretative realities in an endless cycle of creation and distortion.

I don’t pretend that I am capturing the truth about my subjects. I’m interested in creating something that feels timeless, that could have been made at any moment. I think this makes the images stronger—there is more mystery, more opportunity for viewers to bring their own stories to an image that is not fixed in time or place. It allows us to dream, to imagine, and opens up the opportunity for narrative.

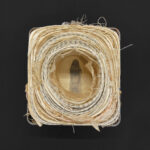

From the beginning, I aimed to create work that exists in the real world, that lives and breathes and ages. I wanted to create things I could hold in my hands, not just see on a screen. Initially this meant making prints, working in platinum palladium and cyanotype. With time, that has evolved into object-making, combining photographs with found objects and written words, including my own poetry. When I assemble a piece, I fix the image in a specific context that I am defining. I use both found photographs and my own photographs to weave new narratives and scenes, presenting them in vintage tins and boxes. The found objects bring their own histories and animism: I feel the hands that have touched them, the care that it took to make them. In a way, I am trying to pay tribute to that labor.

I often wonder why I am drawn to working with vintage photographs. As I look back on these faces from the past, I imagine the lives that have come before. I believe we are tethered to our histories—not bound by them, but ineluctably linked nonetheless. The thread that connects us to the past grounds us and helps us understand our place in the world. I return to what drew me to photography in the first place: that desire to make a mark, to leave behind something that will endure. I appreciate that this is a futile endeavor. We are like gossamer in the morning, vanishing by sundown, and our time here is fleeting. My work circles these questions of time and presence, of what turns to dust and what remains.

Sal Taylor Kydd is a Maine-based photographic artist and writer. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally and is in collections including the Getty Museum, Bowdoin College, Peabody Essex Museum, and the University of New England. www.saltaylorkydd.com; Instagram: @sal.taylorkydd