Manu Larcenet. The Road: A Graphic Novel Adaptation. Harry N. Abrams, 2024.

A 1-megaton thermonuclear weapon detonation begins with a flash of light and heat so tremendous it is impossible for the human mind to comprehend. One hundred and eight million degrees Fahrenheit is four or five times hotter than the temperature that occurs at the center of the Earth’s sun.

…

Not a single thing in the fireball remains.

Nothing.

Ground zero is zeroed.

…

Most won’t make it more than a few steps from where they happen to be standing when the bomb detonates. They become what the civil defense experts referred to in the 1950s, when these gruesome calculations first came to be, as “Dead When Found.”

—Annie Jacobsen, Nuclear War: A Scenario

IN AUGUST OF 1994, when I arrived in the town of Lawrence as a freshman at the University of Kansas, it didn’t take long to encounter the legend of The Day After. Numerous upperclassmen of a certain 1980s nostalgic persuasion communicated to me that this relic of popular culture was required viewing for KU students. The urgency came from the fact that much of the primetime 1983 made-for-TV movie was filmed in Lawrence, some of it inside the Jayhawks beloved basketball cathedral, Allen Fieldhouse.

The cast reads like a 1980s Hollywood fantasy draft, including Jason Robards, Steve Guttenberg, John Lithgow, and JoBeth Williams. The plot follows classic first-person disaster flick tropes, those on-the-ground, tick-tock depictions of catastrophe that, though familiar to me now, were brand new to my eighteen-year-old mind.

Despite the anodyne cinematography, special effects that look rinky-dink compared to Oppenheimer, and a color palette more suited to an episode of The A-Team than serious cinema, the movie really scared me. Given that it was a campus-wide punchline, I was a little embarrassed that the story had such a profound effect on my subconscious.

Raised on the fantasy space-age genealogy of Flash Gordon, my heart was formed in the optimistic mythos of the Star Wars era. Like any self-respecting nerd, I had seen The Terminator and T2: Judgment Day (one of few movie sequels better than the original). But the graphic visions of nuclear holocaust in those films conjured no more dread than the explosion of the Death Star. I didn’t weep for the millions of Californians vaporized along with Sarah Connor any more than for the 1.7 million stormtroopers, military personnel, and civilians who perished at the hands of a teenager from Tatooine. Yet The Day After, with its cartoonish visuals and dated fashions, gave me nightmares.

I was not alone in this reaction, though mine came eleven years after one hundred million Americans watched its first broadcast. If you are under forty, you have probably never heard of this relic, but, like the 1978 film of Watership Down, this particular piece of visual culture haunted many Gen X youth. ABC, fearing a public panic, set up hotlines with counselors for those disturbed by the shocking content. I did not grow up in the duck-and-cover era of Cold War anxiety. By the time I arrived in the world, the hourly fear of World War III that hovered inside every baby boomer’s subconscious like tinnitus had faded—or rather it had grown abstract. What made The Day After so powerful was the intimate frame of the narrative. It closely follows the emotions of just a few characters. It requires the viewer to sit with the shockingly raw cost of a world torn apart in minutes.

Both The Day After and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road use the same magic trick: They transform deep fears from abstract possibility into granular particularity. Like The Day After, McCarthy’s 2006 novel became an instant cultural touchstone. On page one, we enter in medias res, without explanation or preamble. The entire world has been destroyed; only a heap of ashes, bodies, and wreckage remains. A father and son are on a journey south, searching for a warmer climate, adorned in the decayed scraps of a once vibrant world. The unnamed father grasps at the faintest notions of hope to offer his son, but the bleak landscape and a pursuing faction of cannibals suggest a grimmer future.

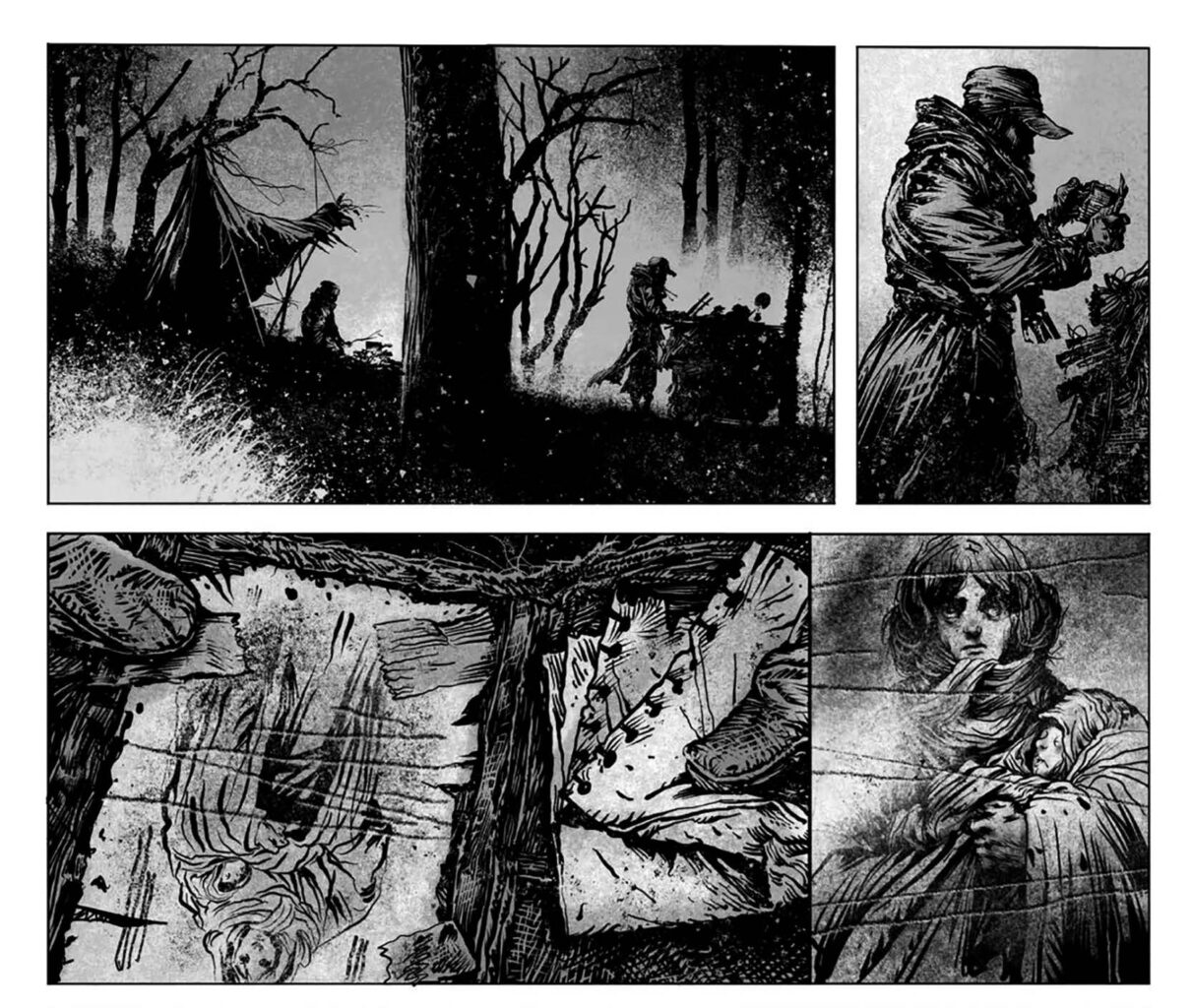

Manu Larcenet’s 2024 graphic novel adaptation recreates the illusion performed by the original novel, and somehow the wonder of the story has not dimmed. The acclaimed French comic artist spent years on this magnum opus, and it shows. Though Larcenet’s stunning reworking contains passages of the barest dialogue, the story has been stripped of McCarthy’s vivid prose. In concept, Larcenet’s story functions almost like a wordless picture book—the drawings communicate the story by being the story. The effect is similar to that of Shaun Tan’s 2006 masterpiece, The Arrival, a fantastical and totally visual rendering of an immigrant’s story that functions as both silent film and picture book. Tan’s drawings seamlessly guide the reader through familiar and metaphorical terrain. In The Road, Larcenet’s drawings do the same work of navigation, providing a steady compass for the reader.

His choices allow the viewer to drink in the intimate details of the ruined world. Despite the urgency of the narrative, our eyes linger on each panel. The monochromatic tones are occasionally broken by a scrap of visual ephemera blowing through the wasteland. A soda can, a box of matches, or a can of baked beans becomes a silent time capsule. They remind the viewer that there once were art directors and type designers who cared about leading, letterform design, and Pantone colors. The complexities of that vanished world crumble into literal ash in the father’s hands. His son has no memory of that world. Panel by panel, the reader is marched through a shadowy version of an earth we barely recognize.

In a striking choice by the artist, the human figures (both dead and alive) have the same visual texture as the environment. In many graphic novels, the characters are designed to stand apart from the background, but here the father and son disappear into the apocalyptic heather. The jagged ripples of their clothing and skin match the cracks of the fractured world around them. It is often hard to see where the humans end and the tattered world begins. Each skeletally thin character is wrapped in a burial shroud of trash. The father and son walk through their inhospitable world dressed like the Christ child, in swaddling clothes, with no place to lay their heads.

When I first heard of Larcenet’s new work, I was skeptical. Book-to-graphic-novel adaptation is a tricky business, and I wondered if it was possible to add anything new to The Road—a work that was, to me, singular and profound. Add to that the unease caused by a recent story in Vanity Fair alleging that McCarthy had a relationship with an underage girl in the 1970s, and the project seemed fraught with challenges. Over the last ten years, in the wake of #MeToo and a long-overdue expansion beyond the traditional Western art canon, many have reconsidered how we should or should not experience art. Speaking personally, I think of art as one of God’s common graces, an undeserved gift given to the world to be enjoyed, not contingent on any single person’s righteousness, faith, or character. Said another way, I believe it is possible to enjoy art while holding multiple truths in tension, including truths about the people who made it. Yet I don’t begrudge anyone who draws the line more starkly. There is good reason to be thoughtful about how we participate in culture. Whatever is true of McCarthy, Larcenet’s book deserves attention simply because his drawings take ownership of the story. This telling is Larcenet’s as much as McCarthy’s.

Some may argue that this kind of adaptation is by its very nature a diminishing of the original, that it is inherently impossible to create anything that matches or eclipses the source material. Sequels, remakes of classics, and films based on popular novels now make up a majority of Hollywood’s annual production. I’m no film critic, but to my mind, although the 2009 Viggo Mortensen vehicle was faithful to the plot points, it never captured the true beauty of the novel. In the space of only a few pages, Larcenet’s telling made clear what the film adaptation was missing.

Nuclear war is not specifically named in the novel as the explanation of the doom surrounding the father and son. The movie adaptation does suggest early on that we are witnessing the hollowed-out world of nuclear winter. The ambiguity of the novel may frustrate some readers, but a crisp explanation of cause and effect is not the author’s concern. Neither McCarthy nor Larcenet is interested in the question of how it happened, rather in what remains afterward. Larcenet’s tangled tableau of ink and smoky tones asks that question in a way that somehow reaches beyond McCarthy’s original work.

Have you ever wondered why human beings seem to enjoy fantasizing about our own extinction? Clearly, some consider this kind of art a form of disaster porn, and I agree that an unhealthy portion of contemporary popular art fetishizes death as entertainment. At first glance, The Road may seem no different from The Walking Dead. Why would an artist choose to spend years drawing the uncanny remains of a destroyed world? It is natural to wonder what exactly is good, true, and beautiful about marauding cannibals. Some have argued that The Road is tedious, depressing, and even evil. So, why illustrate the darkest fantasies of the human heart in a comic book?

The greatest human technology ever created is the codex: double-sided pages bound together with a spine. Even within that ancient lineage, comics do something special. Words and pictures in context form a kind of covalent bond. Presented with the pages of the humble comic book, the human brain does its finest alchemy. Text and image form a kind of enchanted intersection, a third thing that neither can do alone, a unique mineral compound. The mind effortlessly creates a gestalt, a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. This third eye gives the gift of synthesis, of making meaning. Apocalyptic fiction, as with all real art, can allow a reader to strip the world we know of its veneer. In McCarthy and Larcenet’s The Road, human existence has been stripped down to the studs: Hunger. Cold. Fear. Quest. Meaning. Love. Books that peek behind this particular curtain may give you the odd sensation of rubbernecking, the pull to gaze upon something forbidden, a possible future we can’t normally bring ourselves to imagine. Despite ourselves, we slow down and gawk at the horror.

Larcenet’s gorgeous drawings themselves create a wonderful new tension. How can something so awful be so strikingly beautiful? What McCarthy did in stark, elegiac prose, Larcenet does with kinetic, scratchy images. Quietly walking through the evil ashes is somehow a place you wish to linger. Each page is a formal symphony of designed black shapes, gestural lines, white highlights, and satisfying spatters of texture and tone. Ironically, the endless downed power lines, wrecked vehicles, and lovingly rendered shelves of rotting consumer products reveal a strange truth: The story of The Road is about the impermanence of beauty. Over millennia, humanity has fashioned a lavish cultural tapestry—one that could be erased with the push of a button.

The visual world of The Road forces us to hear the quiet question lurking behind every happy moment in our lives. All our labors, all our loves, all our hopes: Are we all simply living versions of Dead When Found?

At the end, what remains?

*

To you, O Lord, I cry, and to the Lord I plead for mercy:

What profit is there in my death, if I go down to the pit?

Will the dust praise you? Will it tell of your faithfulness?

The author of Psalm 30 asked these questions thousands of years ago, yet McCarthy and Larcenet share them. If the universe is nothing but a cosmic eddy of haunted protons, then human beings are a remarkable, albeit temporary, compound. These writers tell us we are all on the road. It is the road that leads to death.

From McCarthy’s novel:

He walked out in the gray light and stood and he saw for a brief moment the absolute truth of the world. The cold relentless circling of the intestate earth. Darkness implacable. The blind dogs of the sun in their running. The crushing black vacuum of the universe. And somewhere two hunted animals trembling like ground-foxes in their cover. Borrowed time and borrowed world and borrowed eyes with which to sorrow it.

It is tempting to imagine the author shares the darkest musings of The Road’s protagonist. I confess that through much of the book it feels as if McCarthy is arguing that joy is for suckers. Will not every good thing turn to ashes in our mouths? Larcenet’s version also seems to say, Look around. Isn’t it obvious there’s no such thing as eternal flame? A notable omission from Larcenet’s adaptation is, arguably, the most famous symbol from McCarthy’s novel. In Larcenet’s version, the father and son never speak of “carrying the fire.” Larcenet may have wanted to avoid stepping on the poetry of the original, and certainly the core sentiment—that the father and son represent a remnant of what was best in humanity—is still present in this telling. But to be honest, I did miss seeing those words from McCarthy’s version in black and white:

We’re going to be okay, aren’t we Papa?

Yes. We are.

And nothing bad is going to happen to us.

That’s right. Because we’re carrying the fire.

Yes. Because we’re carrying the fire.

McCarthy never explains precisely what “carrying the fire” means. But this simple phrase is the father and son’s most sacred liturgy. It dwells within them both. The mystery sustains them. Shekinah is the Hebrew word for the majestic and uncontainable glory of God somehow dwelling upon the earth. Most notably, we see this Shekinah glory in the story of Moses meeting God in the burning bush. This strange fire is unquenchable, but as it dwells in the branches, the leaves are not harmed.

The Road is a page-by-page struggle between two counternarratives. Is the universe empty, or does something truly remain? We never meet the boy’s mother. We learn that she chose to end her life rather than face a universe without hope or meaning. In one of the most heartbreaking sections of the novel, the father remembers pleading with his wife to stay with them. He begs for hope. She responds with existential resignation, “We’re not survivors. We’re the walking dead in a horror film…. As for me my only hope is for eternal nothingness and I hope for it with all my heart.” She will not carry the fire. The father could not convince her to believe that they are anything more than Dead When Found.

These two parents represent the gorgeous tensions rendered by McCarthy, and now Larcenet. Both versions of The Road orbit these two concurrent yet paradoxical stories: The universe is cold and cruel. Yet the human heart, a product of that same universe, flickers with an unreasonable light. This new story carries that same fire. The Road dares us to believe that something, or someone, dwells within us—an unquenchable flame that burns but does not consume.

Image credit: Manu Larcenet / Abrams ComicArts

John Hendrix is a New York Times bestselling author and illustrator whose books include The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler (Abrams). His most recent graphic novel, The Mythmakers, was named a best children’s book of 2024 by the New York Times.