Adam Belt’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at venues including the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego; Quint Gallery in La Jolla, California; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; Franklin Parrasch Gallery in New York; and RCM Galerie and Topographie de L’Art in Paris. His artistic practice is a contemplation of physical and phenomenological aspects of our world, the cosmos, God, and religion. An active member of the Episcopal Church, he lives in Carlsbad, California.

Image: You’ve spoken about your art practice as a form of calling or vocation. Are those terms you’ve always used to describe your work, or has that awareness emerged over time?

AB: I recall that terminology developing early on, after I transitioned from traditional landscape painting to creating installation works using physical phenomena, like ice moving over a bed of sugar or paint flowing over panels. In my mid-twenties, I decided to attend graduate school in art. Before this, I’d had a sort of underlying understanding that art was a way to engage the mystery of the unseen—the infinite as expressed in the physical world—in a way that church and religion could not. The decision to pursue art helped codify this understanding for me.

Adam Belt. Through the Looking Glass (James Webb Telescope Mirror), 2011. Two-way mirror, mirror, wood, and LED lights. 72 x 72 x 3½ inches.

Image: A lot of your work tackles both scientific and spiritual subjects. Do you find that one of those elements often comes first, or do they tend to coincide?

AB: For me it’s more that there is a space beyond, a space where there is no differentiation. That’s where the work begins.

Image: You seem especially interested in elements that do unexpected things within spaces like galleries that are usually very controlled. Can you talk a bit about those processes and what kind of spiritual connections emerge through them?

AB: I’m really drawn to natural phenomena, like crystals growing, or sand dunes drifting through the space, or a layer of fog suspended in the air. I love instances where the form is not derived from metaphor or necessarily deliberately shaped. The form grows through inherent, unseen forces and processes, influenced by conditions in the space like humidity, temperature, or even the movement of visitors. The sterile, often antiseptic environment of the art gallery or exhibition venue is ripe for contrast. The challenge is to foster an encounter that can defy visitors’ expectations and create a work or experience that can really breathe.

Adam Belt. Font (Oval), 2019. Mixed media, water, crystal-growing solution, copper filings. 36 x 32 x 42 inches. Photo: Philipp Scholz Rittermann.

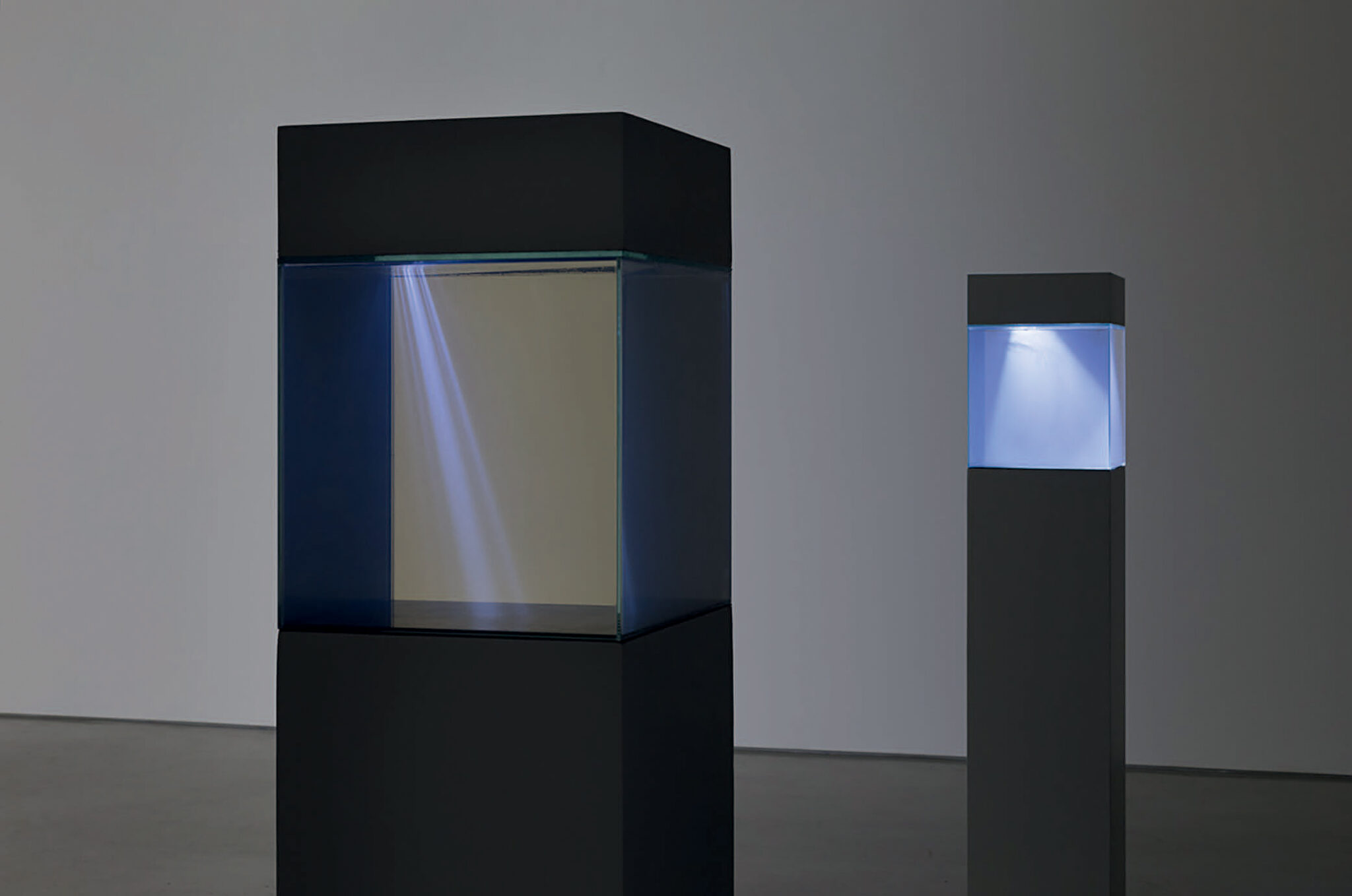

Adam Belt. Reliquary (Lightrays), 2013. Sunlight, solar panel, battery, electronic components, light, water, glass, and wood. 67¾ x 14 x 14 inches. Photo: Philipp Scholz Rittermann.

Image: A number of your works reimagine traditional ritual objects such as baptismal fonts, reliquaries, or rosaries. Do you see these objects as having a liturgical function?

AB: Often I am creating an object that I want to see in the world, and I don’t think about context until later. I have created a baptismal font for a church based upon a natural hot spring at Yellowstone National Park, but the crystal-growing fonts I’ve created elsewhere wouldn’t work for use in church. They’re made with a manmade salt solution that forms crystals as the water evaporates, and while the fluid isn’t dangerous, it’s nothing you’d want to stick your hand into or ingest. (At shows, I always know who has touched the fluid by who asks me whether it’s toxic.)

I’ve created a rosary of meteorites that is quite large, sort of Flavor Flav sized, but I would love to create smaller versions. Holding something from outer space in your hand and praying with it heightens the awareness of God’s creation beyond your immediate surroundings.

One idea that only exists in drawing form is Altar of Ages. The altar would consist of thirty layers of rock arranged in order of age, from 4.6 billion years old (from the Campo del Cielo meteorites) on the bottom to zero years old (from an I-5 freeway expansion) on the top. I did make a smaller work called Rock of Ages composed of those same thirty layers.

Adam Belt. Phase Form #1, 2021. Polyurethane resin. 12 x 12 x 12 inches.

Image: What kinds of spaces would you like to see your work exhibited in?

AB: I would love the opportunity to exhibit in and interact with sacred spaces. I think my work might be more fully realized there. The typical gallery context carries so many assumptions and burdens that come from the cultural conditioning and history of contemporary art. While there is a growing openness to the spiritual and religious, there is still a lingering and palpable taboo against it. Religious contexts open people up to the possibility and even expectation of a spiritual encounter, while also engaging an audience beyond the narrow contemporary art community. Outside of preordained art spaces there exists greater possibility for surprise and wonder.

Image: What projects are you working on at the moment?

AB: Currently I’m working on cast polyurethane resin blocks that interact with the light of the space they occupy. In one series, the blocks transition from an opaque white to transparent. I cast forty-five to sixty layers, calculating a varying amount of opaque white to create the ombre. My desire is to remove meaning and allow for presence to be the focus. This quote from Thomas Merton resonates with me in relation to this new direction: “But there is greater comfort in the substance of silence than in the answer to a question.” Earlier I mentioned my intuition about art as a means to engage the infinite. That idea is at the core of this work.

Adam Belt in his studio. Photo: Lile Kvantaliani