WALKING THROUGH THE EARLY RENAISSANCE GALLERIES of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, one encounters portraits of the saints in gold altarpieces, brightly colored biblical narratives, and triumphal crosses depicting the suffering Christ. One figure, however, arrests the viewer with a direct gaze, offering a tray of milk and honey. Despite the glittering background, this man’s bright white T-shirt and dark skin contrast with the devotional portrayals in the surrounding gallery. Are You Being Served? (2014) was displayed as part of a special exhibition in 2022–23 that paired Renaissance and contemporary work. A painting by Stephen Towns in acrylic on panel, it uses the early Renaissance devotional aesthetic to address modern social injustices.

Towns is one of many contemporary artists who have appropriated, critiqued, and subverted the religious art of the Renaissance. Why do artists like Towns look back to this period to express their personal experiences or make statements about social and political issues? What is it about the familiar visual vocabulary of the Renaissance—the haloes, the gold leaf, the careful arrangements of figures—that makes it so ripe for borrowing?

The resulting works range from postmodern pastiches and subversive critiques to more personal and poetic pieces, but they share some characteristics. First, in their emphasis on figuration, narrative, relationships, and community, they react against abstract, conceptual, and installation art, thus appealing to traditional institutions and the general public. Second, by referencing a period that is arguably the stylistic and theoretical basis of Western art, these artists audaciously situate themselves within a long art-historical tradition that confers an intellectual weight.

Moreover, in the twenty-first century, a dialogue with the Renaissance cannot be thought of without reference to the nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists who pioneered it. In 1863, Édouard Manet famously updated Titian’s Venus of Urbino in the guise of a Parisian courtesan named Olympia, and in 1919 Marcel Duchamp drew a moustache and goatee on a postcard of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. Contemporary art, therefore, not only responds directly to Renaissance masters but represents the latest incarnation of a modernist trope.

The Ironic Postmodern Pastiche: Subversion and Identity

No work of Renaissance devotional art has attracted contemporary artists more than Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1495–98). Painted in tempera on a thin wall in a humid church, the fresco began to deteriorate before it was ten years old. In their analysis of the work’s afterlife, Francesca Bonazzoli and Michele Robecchi concluded that its rapid degradation led to its wide dissemination via reproductions rather than it being observed directly. In this way, “it can be considered an unfinished and infinite work,” which can “always be interpreted, modified, and reproduced.” Contemporary artists’ versions, therefore, are just the latest in a long history: in the centuries since its creation, The Last Supper was “re-created” though a series of controversial restorations and reproductions.

Andy Warhol used nineteenth-century photographic and illustrative reproductions to produce his two silkscreen print series Details of Renaissance Paintings and The Last Supper. The latter series appeared in 1987 in what would be Warhol’s last exhibition before his death, shown in a Milan art gallery just opposite the monastery containing Leonardo’s original mural. For his Last Supper series, Warhol borrowed a simple line drawing from an 1885 encyclopedia of painting to create images in what he called his plagiarist style. Eschewing the reverence traditionally granted to the Renaissance, Warhol used repetition, bright colors, and commercial logos to criticize the commercialization of religion and imply its replacement by capitalism.

Like most Renaissance artworks, Leonardo’s mural was a site-specific piece designed for a particular patron, audience, and devotional setting. Modern and contemporary versions, on the other hand, have tended to divorce it from its religious context. Instead, it variously serves as a symbol of male privilege and power, the classical canon, colonial oppression, and empire building. Several contemporary versions flip the narrative to place oppressed peoples in positions of power.

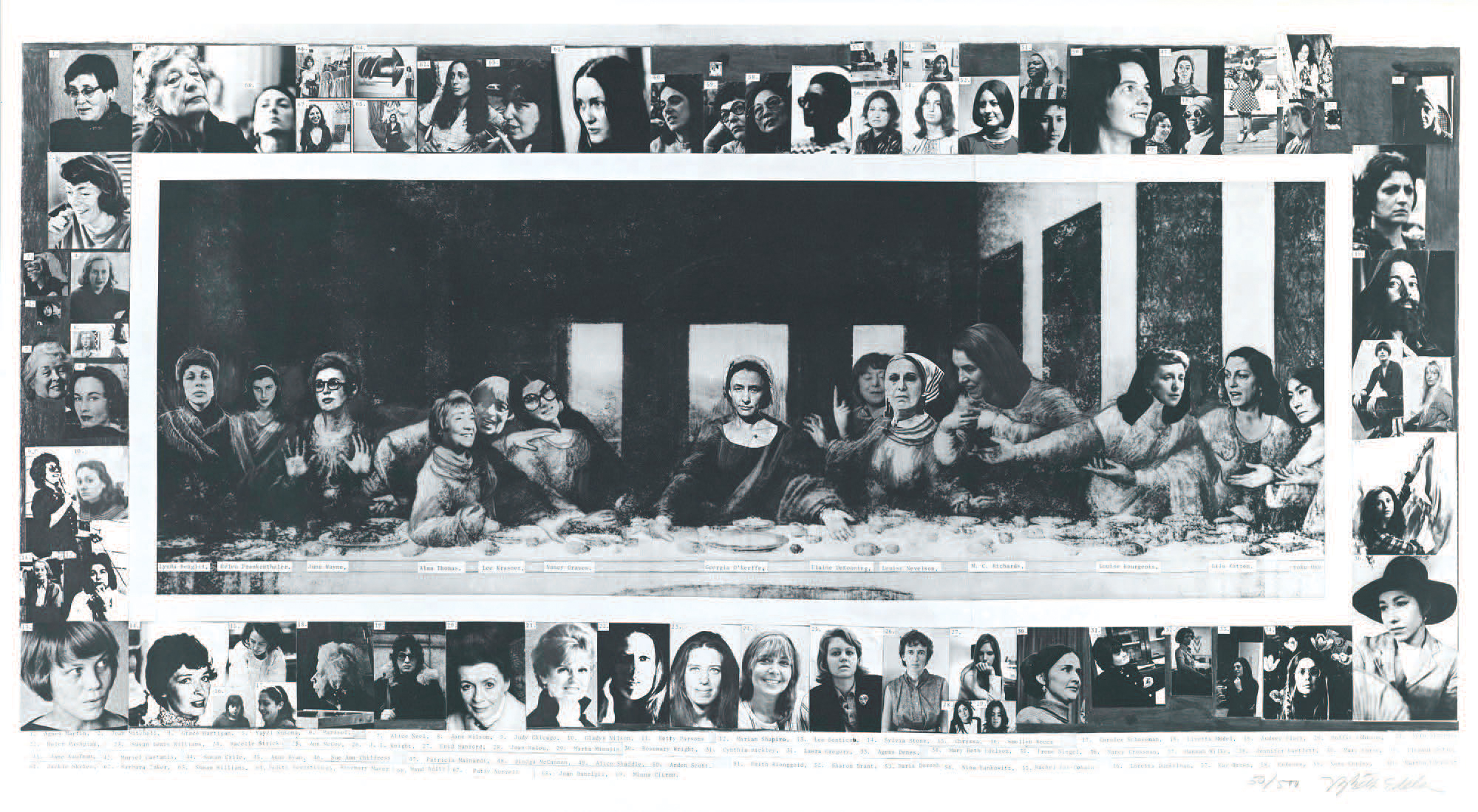

Mary Beth Edelson. Some Living American Women Artists/Last Supper, 1972. Lithograph on paper. 25 x 38 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Benjamin P. Nicolette.

Before Warhol, in a 1972 poster collage titled Some Living American Women Artists/Last Supper, Mary Beth Edelson pasted cut-out heads of female artists onto a reproduction of the Last Supper, with Georgia O’Keeffe playing Christ. More women artists, all labeled, formed a border. Edelson said she “wanted to prove that [organized religions] are no longer a major cultural force that subordinates women.” With its small size, grayscale color scheme, typewritten labels, and almost amateurish lack of refinement, the work contrasts dramatically with Leonardo’s monumental mural. Edelson’s photomontage captures a variety of facial expressions, from Alma Thomas’s confident smile as Judas to Helen Frankenthaler’s sultry, piercing gaze as James the Less. Like contemporary internet meme culture, the collage uses a layer of humor to disarm and engage the viewer, who only upon reflection considers the injustices that were the target of the women’s liberation movement.

In Edelson’s wake, artists from a variety of backgrounds have produced Last Suppers that subvert societal norms. In his 2013 installation Last Supper Exploded, British Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare arranged headless, life-sized mannequins at a table laden with silverware, glassware, resin food, and fake tulips. By dressing the figures in Dutch wax-printed cotton, a marker of West African culture but also of a complicated colonial history, Shonibare encourages viewers to reconsider perceptions of the exotic and reframe the cruel history of Europeans in Africa. The central figure is Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, here represented as a goat-footed satyr, while the surrounding figures strike poses of debauched exuberance in a critique of the worship of financial excess. Unlike Edelson’s expressive faces, Shonibare’s figures are decapitated and immobile, as if frozen in time. While the artist intended their headlessness to deter racial interpretations, one cannot help but associate it with lack of representation and even violence.

Bringing these postmodern pastiches full circle, Japanese artist MADSAKI used spray paint to create his 2019 The Last Supper (The Big C) II (inspired by Andy Warhol), an irreverent reflection on originality and replication. MADSAKI’s copy of a copy of a copy reminds us that when contemporary artists reference The Last Supper, whether they want to or not, they pay homage to that most ironic of modern artists, Warhol himself.

In fact, Leonardo and Warhol were recently paired in an exceptional auction that further reinforced the relevance of the Renaissance master in the contemporary art world. Salvator Mundi, an oil painting variously attributed to Leonardo or his workshop, was included in Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale in November 2017, when it sold for a staggering $450.3 million, reportedly to an intermediary for the crown prince of Saudi Arabia. Rather ironically, considering its plagiarism of Leonardo, Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers sold in the same auction for $60.9 million. Former vice president of Sotheby’s France Nicolas Joly later called putting the controversial rediscovered painting up for sale alongside contemporary art “a stroke of genius.” Whereas typical Old Master clients carefully debate questions of attribution and restoration, he surmised that bidders in the contemporary sale simply wanted “to buy the name.” For the first time in its history, Christie’s employed an outside marketing agency to launch an extensive campaign, including a worldwide tour and a video featuring awestruck and tearful visitors—including another Leonardo, this time DiCaprio—encountering the masterpiece.

In response, New York–based contemporary artist Jordan Eagles created Jesus, Christie’s, whose playful title cleverly juxtaposes religion and capitalism (and which appeared on the cover of Image issue 105). Eagles inserted twelve vials containing the blood of an HIV-positive survivor into a copy of the Christie’s sale catalo. Obscuring the eyes of Jesus but revealing the gold Christie’s logo below, the twelve vials recall the twelve apostles as well as medieval reliquaries, but the blood itself, unlike the redemptive blood of Christ, communicates the exclusion, fear, and ostracism experienced by HIV-positive people. This unsettling and provocative work not only criticizes the excessive wealth brought to light at the Christie’s auction but also uses the universal motif of blood to contrast religious salvation and social exclusion.

In its critique of the overblown status of Leonardo, Eagles’s work invites reflection not only upon the influence of the Renaissance master but, conversely, on how modern art has revised cultural perceptions of Leonardo. The way modern artists from Duchamp and Warhol to Eagles and MADSAKI have feverishly reproduced, repopulated, and resituated Leonardo’s devotional work has magnified his art-historical importance well beyond that of his peers, leading to astronomical auction prices and a celebrity status that would have been unrecognizable to a sixteenth-century audience.

Illuminating Injustice

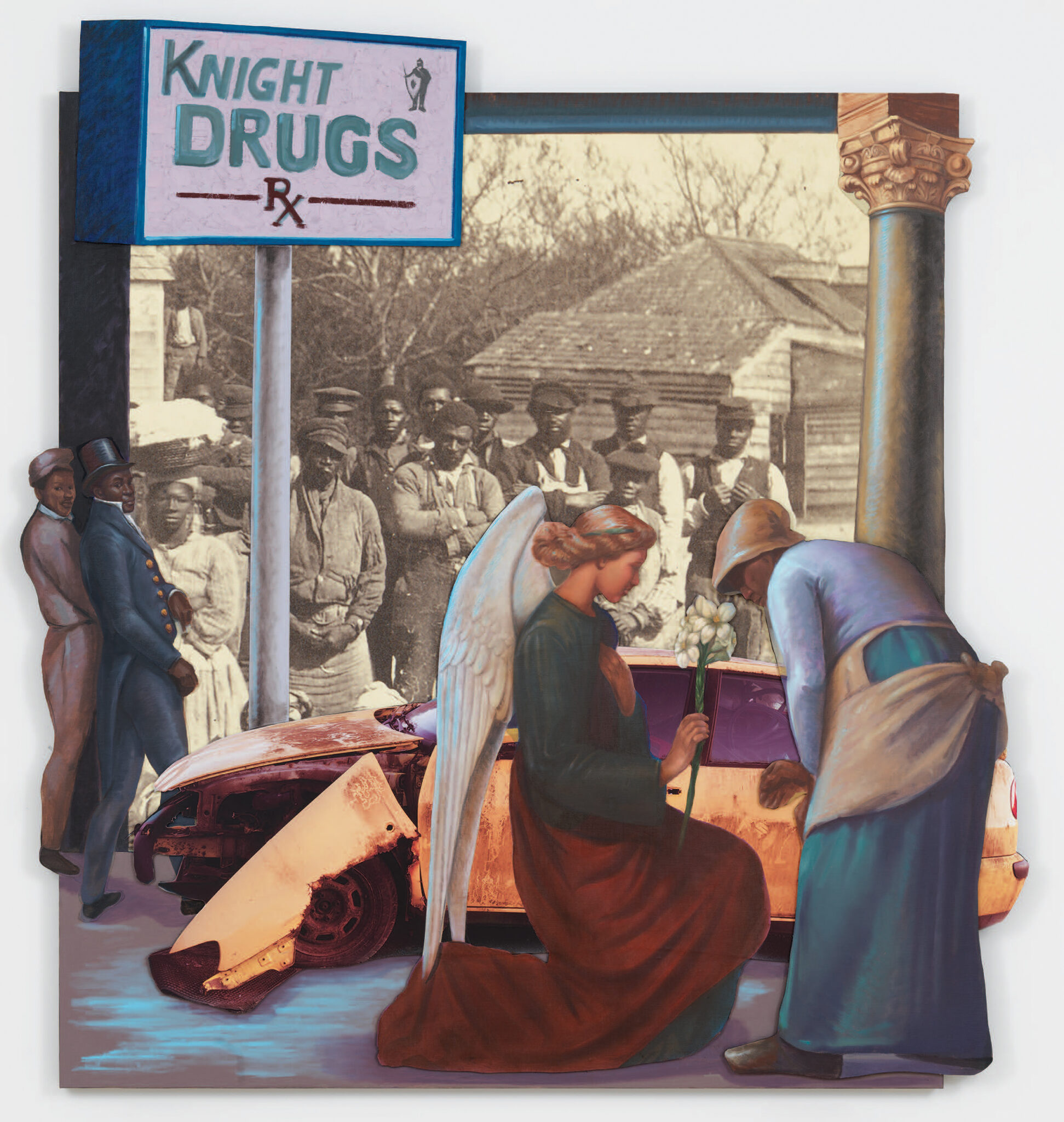

Titus Kaphar. New Enunciation, 2021. Oil on canvas, vinyl, and wood. 77¼ x 73 x 2½ inches. © Titus Kaphar. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

Contemporary American artists have likewise referenced Renaissance devotional art to cast light on social and racial injustices. Titus Kaphar, an artist known for using art history to expose uncomfortable truths about ingrained racism, has incorporated quotations from Renaissance devotional paintings in his latest works, displayed in New Alters: Reworking Devotion, his first exhibition in London, at the Gagosian Gallery in 2022. Combining images of Black workers taken from nineteenth-century American photography, careful replicas of triumphant American paintings, gilded frames, and fragments from Renaissance altarpieces, the artist creates palimpsests of discordant and ahistorical figures that challenge contemporary views of race and class. For example, in New Enunciation, a feminine Renaissance-inspired angel Gabriel approaches a stooped Black field worker whose pose is quoted from Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners, against a backdrop of reproduced photographs of a broken-down car and a field of enslaved Black workers. Two smartly dressed nineteenth-century Black men look on as they stride past. Echoing the architectural backdrops of Renaissance Annunciations, a classical Corinthian column is paired with a store sign for Knight Drugs, a pharmaceutical company based in Kaphar’s home state of Michigan. Kaphar not only juxtaposes tradition and modernity but also the need for spiritual and physical healing. Taken out of historical time, the angel appears to approach the woman with a message of salvation and hope, perhaps even freedom from oppression. But the stark contrast between the angel’s white skin and the surrounding Black figures also implies a critique of the white savior trope.

The trend of using of Renaissance religious art to highlight social problems shows no sign of abating. The recent Activating the Renaissance exhibition at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore is a case in point. Exhibition curator Joaneath Spicer noted that the “return to the human form and the importance of storytelling [in contemporary art] have opened the door to a range of deeply meaningful conversations across time.” In fact, displaying contemporary artists like Stephen Towns and Jessica Bastidas alongside centuries-old work gives museums a chance to expand their audiences in two ways: fans of the contemporary who might rarely visit traditional museums are exposed to historical art, while those who prefer the familiar Renaissance and Baroque masters are offered an approachable and palatable engagement with new work. I can certainly understand why this approach is popular with curators and the museum-going public, since it is figural and relatively comprehensible, especially compared with most conceptual and installation art. The Walters exhibition was intended to “activate” their Old Masters collections, and indeed Spicer noted that the show was attracting a “remarkably engaged visitorship, given that much has depended on word-of-mouth.”

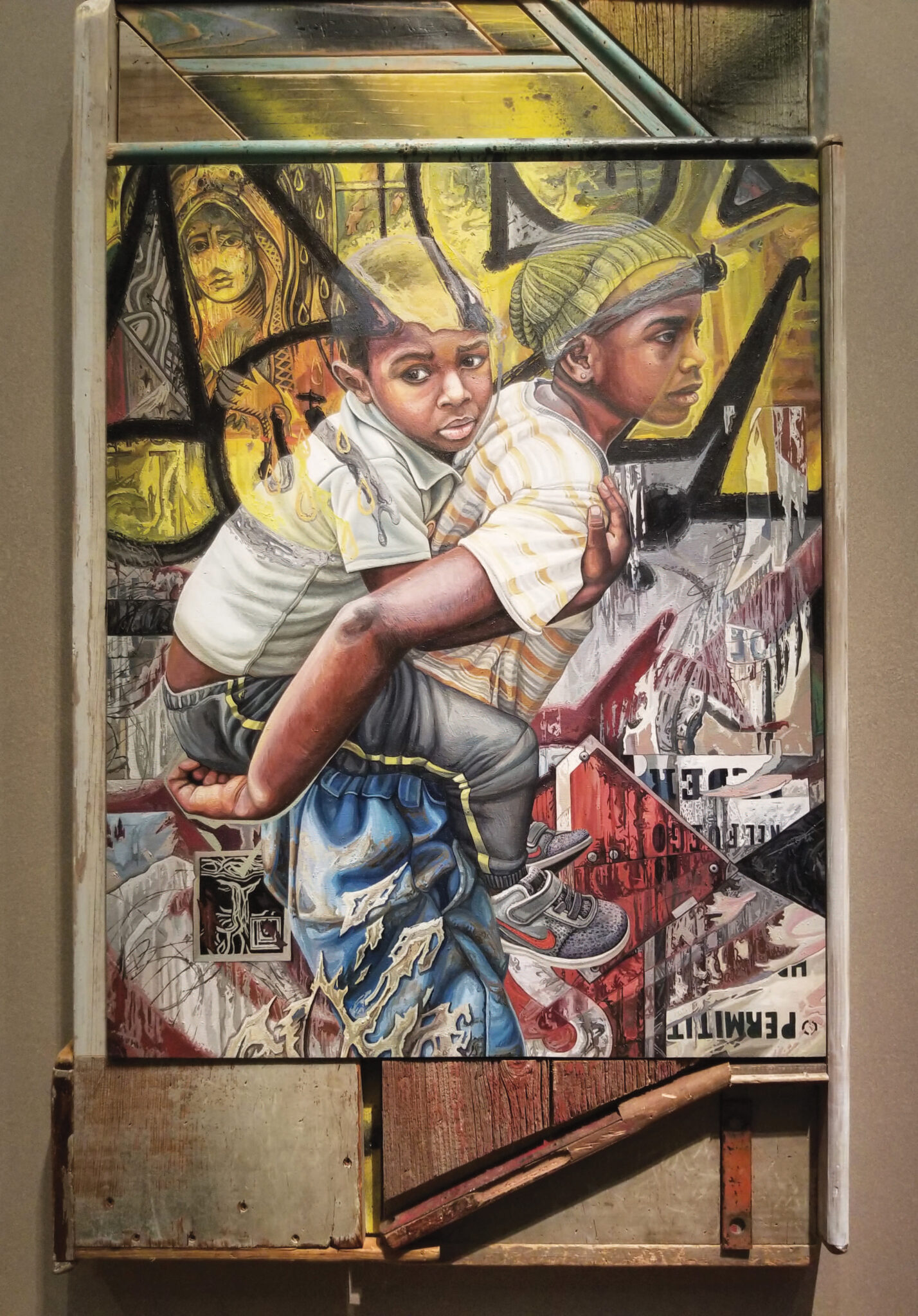

Jessica Bastidas. Tears of the Black Madonna, 2021. Oil on panel. 30 x 24 inches.

The artists included in the show have specifically engaged with the tropes of European art collections such as that held by the Walters. Towns’s painting asks (in the artist’s words) “if contemporary Black Americans have been served the wealth and riches that their ancestors have worked and died for.” Jessica Bastidas’s Tears of the Black Madonna shows a boy carrying his frightened younger brother on the streets of San Francisco, where graffiti mixes with a Latinx-inspired Madonna. While the framing of the naturalistic figures echoes Renaissance artists like Fra Filippo Lippi, Bastidas hoped to communicate “how the traditional notion of family, embodied in the Holy Family, has evolved.”

Spicer mentioned the special significance of seeing works by African American and Latinx artists “looking very comfortable, effortlessly sophisticated, and at ease in these groupings” (most were placed alongside Italian and northern European art of the Renaissance and Baroque periods) especially considering that “European cultural expressions of the past may represent a society that wouldn’t necessarily have accepted them.” These spatial juxtapositions, therefore, as well as the contemporary works themselves, show the power of art to challenge the injustices of both the past and present.

Intimacy Across Time: Iconic Subjects, Personal Responses

In contrast to work that echoes the visual vocabulary of Renaissance work, other artists have responded to its spiritual, emotional, and poetic elements. Work by the American video artist Bill Viola was collected in a 2017 exhibition titled Electronic Renaissance at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. In the 1970s, Viola spent some of his formative years in Florence as technical director of the video production center art/tapes/22, and the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition underscored his career-long engagement with Renaissance art by displaying his work alongside the images that inspired him. While this unique visual dialogue contrasted the Old Masters’ painstakingly detailed painting techniques with Viola’s technologically advanced media, it also revealed just how closely Viola imitated the formal, compositional, and emotional qualities of the earlier pieces.

Bill Viola. Still from The Greeting, 1995. Color video and sound installation on wall in darkened space. Photo: cea+ www.flickr.com/photos/centralasian/8300101701 CC 2.0 license.

A good example is Viola’s short video The Greeting (1995), which references the meeting of three women—the Virgin Mary, her cousin Elizabeth, and an unidentified woman—in Jacopo da Pontormo’s Visitation (c. 1528–29). A Florentine Mannerist known for elongated proportions and a bright, almost garish color palette, Pontormo was the first Old Master to inspire Viola. Captivated by Pontormo’s dynamic draperies, Viola emphasized the flowing folds, colors, and movement of the women’s garments by introducing the movement of wind from the bottom right of the frame. While Pontormo’s painting depicts the joyful yet poignant moment when the pregnant Virgin Mary embraces Elizabeth, who is already six months pregnant with John the Baptist, Viola kept the title of his work generic enough to leave the viewer pondering the reason for this emotional meeting. Nevertheless, the vibrant colors of the robes intensify the moment, while the women’s subtly changing body language and facial expressions create an extended emotional narrative that the viewer witnesses but is never involved in.

In contrast to Warhol’s indirect copy of a copy, Viola worked from an intimate awareness of the original spatial and social context of Renaissance art gained through personal experience. In 2003 he said, “Many of the medieval and Renaissance works I had seen in those first months in Florence weren’t even in museums. They were in the community, in public places—cathedrals, churches, chapels, courtyards, monuments, municipal offices, squares and palaces’ façades—and, even more, many were still in the places they had been commissioned for some five hundred years earlier…. This provided a new context to my idea of art appreciation.” In response, Viola captured the profound stillness, monumentality, and emotional intensity of Renaissance devotional works, but crucially added a temporal dimension with the use of a special three-hundred-frames-per-second camera that produced a super smooth extended slow motion. The scenes Viola creates thus evolve through time and hover between stillness and movement, allowing complex emotional and spiritual encounters to unfold gradually before our eyes.

New York–based painter Elsie Kagan calls her early engagement with Renaissance art “an access point for exploring personal themes within the context of painting.” Not religious herself—she has wrestled with her Jewish heritage and turned away from organized religion—Kagan has used Christian art to explore more universal concepts. For example, in a series based on the Madonna and Child reliefs of Florentine sculptor Luca Della Robbia, she was “trying to work through the simultaneous experiences of motherhood [while] struggling with my own mother’s longtime severe mental illness.” Although the Della Robbias that inspired them are quiet and ethereal, Kagan’s paintings “break from the tranquility of the traditional Madonna and child, instead presenting images in which multiple mothers and children cascade through the compositions, their idealized embraces interrupted by replication, and incompletion.”

Elsie Kagan. Kingdom of Ordinary Time, 2017. Watercolor and oil on canvas. 66 x 48 inches. © Elsie Kagan

In Kingdom of Ordinary Time, the carefully observed face of the Madonna at the top left appears to dissolve into abstracted brushstrokes in tones of vivid ultramarine blue before the relief repeats on the right, where emphasis is placed on the mother’s grasp of the child’s body. The intense and expressive painterly section, which contrasts with the morose visage of the woman and the porcelain-like qualities of the child’s limbs, hints at the multifaceted and paradoxical nature of their relationship. Though the works are deeply personal explorations, Kagan admits that their Renaissance motifs offer viewers a sense of familiarity, making her work accessible to a wider audience.

Viewed more critically, this dissolving of the traditional mother-and-child archetype appears to challenge notions of gender essentialism that would ascribe to women an inherently nurturing role. In another response to the Renaissance Madonna and Child, Israeli-born artist and researcher Leni Dothan has explored the theme of motherhood in her 2011 video work Sleeping Madonna (which appeared on the cover of Image issue 102). Replicating a traditional Virgo lactans image, the artist reveals a naked breast, but this time to a relatively uninterested child (the artist’s son). While the round-arched niche brings to mind serene Renaissance Madonnas, Dothan’s video instead conveys the quotidian boredom of motherhood, thus disarming the oppressive potential of this hallowed theme.

This use of Renaissance imagery to think through facets of humanity can also be seen in the work of Kehinde Wiley, who famously reproduces historical paintings replacing white figures with Black men. Borrowing imagery from the Annunciation and Deposition, standing saints in stained-glass windows, and small devotional altarpieces, Wiley paints his models in a photorealistic style, in faithfully replicated art-historical poses. By working with non-professional models, whom he often meets in everyday contexts, he elevates young Black men to positions of power, emphasizing their human dignity. The figures wear contemporary dress and stand against brightly colored decorative backgrounds often derived from African printed textiles. The organic shapes of flowers and leaves seem to float away from the fabric, invading the figures’ spaces. By alluding to the sanctity of these young Black men, Wiley says he aims to change “the narrative of what it means to be resplendent, noble, visible, and celebrated in a painting.”

Viola, Kagan, Dothan, and Wiley’s responses to Renaissance art are notable for their focus on intimate relationships and human nobility—an emphasis for which the Renaissance offers precedent, albeit an ambivalent one, given the treatment of women and minorities during that period. Nevertheless, a Renaissance artist such as Donatello, in his sculpted reliefs, explored the multilayered, varied, and subtle nature of family relationships and the fragility of human life. These contemporary artists remind us that interpersonal bonds are an enduring aspect of humanity, allowing us to feel some connection to people who lived centuries ago.

Despite the increasing diversification of studio-art and art-history curricula at universities, the Renaissance still looms large in Western culture, with devotional art representing some of the period’s most technically advanced, emotionally charged, and instantly recognizable images. Consumption of historical art today is often decontextualized, not only via the internet and social media, but in popular “immersive experience” shows, which present oversized image projections designed to offer consumers opportunities for Instagram-ready photos. Moreover, the replication of historical art in modern settings, as originated in The Last Supper pastiches of the 1970s to the 2000s, is now relatively common in mainstream advertising and fashion. Faddish pandemic-era activities such as the Getty Museum Challenge encouraged people to re-create historical art using everyday household items during lockdown.

In contrast, it is striking that Viola and Kagan, whose work captures the poetic qualities of that period, had significant personal exposure to Italian art in its original spatial and religious settings. Less interested in subversion than connection, they seek dialogue with art of the past, allowing themselves to respond to its beauty in hopes of revealing deeper emotional elements and spiritual qualities that have the potential to transcend time.

Long ago, Old Master saints and biblical figures were something to be encountered only in reverential spaces like museums and churches. For today’s viewers, encountering devotional art among the vast mix of images we consume daily is nothing new. In some ways, that familiarity makes the Renaissance less potent, but contemporary artists have shown that there is something about these timeless masterpieces we can’t seem to forget.

Joanne Allen is a senior professorial lecturer in art history at American University. Her research focuses on art and architecture between the medieval and early modern periods. Her book, Transforming the Church Interior in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge), was published in 2022.