BHARTI KHER has long been intrigued by hybridity. Finding meaning in the inherent plurality of things, she registers this in fluid forms that unsettle the categories we normally use to tidy up the unassimilable wildness of our natures and identities, our habitats and environments, our experiences and ontologies. Her fascination with hybridity draws largely from the sensory apparatus of her own life. She grew up in the United Kingdom, where her mother owned a sari shop in Streatham in south London, but at twenty-two she moved to Delhi, where she immersed herself in Indian imaginative and artisanal traditions. Her art crossed borders with her and never settled fully in one place.

Composite Selves

Installation view of Bharti Kher’s The Intermediaries. Conservatorio Di Musica Benedetto Marcello Di Venezia, Venice, Italy, 2022. Photo: Francesco Allegretto.

At the Venice Biennale 2022, she showed work from her ongoing series The Intermediaries, clay assemblages of parts of golu idols-the diminutive, gaudily painted figurines traditionally used in the Navratri festival, depicting narratives from Hindu scriptures, court, or daily life. Kher found them in South Indian markets and street corners and collected them over the years, giving them a home in her studio and waiting for them to find their new lives, to become the plural beings they perhaps always wanted to be: a god conjoined with a human, a man with a woman, a bird with a dog’s head, a human with bananas sprouting from its neck. Realizing their destinies in an ecology of entanglement across human, animal, plant, and divine worlds, these composite figures project the potential of a multiform world stirring under the surface of the smooth, constructed categories we have come to think of as nature. Ranging from the sublime to the ludic, they present conjunctions that are variously awkward or contorted, whimsical or comic, or extractive of subliminal synchronies.

Kher’s latest hybrid figures, displayed at the recent exhibition Alchemies at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, deepen her exploration of metamorphosis. Animus Mundi, the most Ovidian product of Kher’s mythy mind, blends Harappan hybrids, fluid forms reminiscent of Bernini, and Kafkaesque transformations. She is one of Kher’s sari-clad women-figures who go beyond their cultural situation and evoke the multiple worlds that coexist in the cosmopolis of Kher’s creative brain. (Saris, like bindis-the ornamental dots Indian women wear on their foreheads, also spiritual symbols of the third eye-are a signature component of her work.) Made of dark red resin, this baroque overflow of gloopy whirls of fabric disrupts the sari’s usual delicacy, recalling the livid hearts and visceral fluids of the European Counter-Reformation. With crimson cloth flowing from her mouth, her buffalo head dotted with bindis, Animus Mundi, gagged and gorgeous, is Ovid metamorphosed and Botticelli twisted, an Aphrodite hybridized, as brutality meets beauty on a fine edge. In the main room of the Yorkshire show, this migrant Venus modernizes myth and bleeds the local into the global in consort with other female figures seen as warriors, monsters, mothers, hunters, prophets, and seductresses. Not only does she mingle Western and Eastern imaginaries; she also comes out of inextricably mixed aesthetic traditions internal to India-and not confined to high art.

Last winter, I took a stroll through Kumortuli, the potters’ quarter of Kolkata where idols for public pujas (religious festivals) are made. There was not the buzz around the warrior goddess Durga and her entourage that fills the scene in the lead-up to the biggest puja in autumn, but there was a quieter hum of activity around Saraswati, the goddess of learning and fine arts who visits the earth in February, often carried by a swan. But in one corner I found a Durga in the making, stunningly stylized, her personhood almost symbolically distributed: the head of the lion she rides was taking shape on one side of the clay wall behind her.

The trunk of Ganesha, her half-elephantine son, emerged from the other. At her feet, Mahishasura, the shape-shifting half-buffalo demon whom she slays, was presented as a mask on the head of a calmly seated man with a curiously gentle face: the human and the monstrous placed in contiguous but distinguishable relation. How similar this aesthetic is to that of Animus Mundi and Kher’s other hybrid bodies; how similarly tuned their intuition and acceptance of the disparate aspects of nature-both human and nonhuman-and how they can transform into one another! And how deep the affinities, too, between ideas of the performative self in the West and the East: the bull’s eye could have belonged to Durga herself, and the half mask reminded me of the Greek word prosōpon, used with its full dual charge in Euripides’s Bacchae-meaning both “face” and “mask.”

Bharti Kher. Djinn, 2024. Bronze. 191 x 109⅞ x 191 inches. Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Photo: Jonty Wilde.

Other sculptures magnify the scale of The Intermediaries into the monumental. On the rolling grounds of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park sits Djinn (2024), somber in bronze and over sixteen feet tall. A giant boy-thinker, he sits pensively on the highest point of the park, his head of bananas pointing toward the sun, which lights him as it rises and sets. I saw him first in June, gleaming in the evening light. When I went back in November, his patina had turned steely in the snow. He had become the animating spirit of the place, morphing and moving beyond the artist’s intention and control. The first banana plant imported to the UK came from Mauritius in 1833, but not till the 1880s did wholesale import begin, mainly from the Canary Islands. Djinn is devoted to the space it occupies but also disrupts its narrative. He is not only a plant-child himself; he also hybridizes that quintessentially British landscape, a green slope dotted with sheep that might, in a certain slant of light, morph into bindis.

Oscillations of Scale

Bharti Kher. Ancestor, 2022. Bronze. 205 x 76½ x 80⅓ inches. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Photo by the author, potters’ quarter, North Kolkata.

Kher plays with scale throughout her oeuvre, and bindis are perhaps her primary tool to explore the subliminal connection between our smallest constituent cells and something infinitely vaster. The word bindi derives from the Sanskrit bindu, or particle. They feature across her art as atoms, motes, dots, and spots at one end of the scale, and celestial orbs and aerial landscapes at the other. While this oscillation of scale is partly a function of her desire to grasp the relation between the cellular and the cosmic, on another axis it is politically subversive.

The world does not lack colossal statues. India now boasts the tallest: the obscenely costly, ostentatious 597-foot Statue of Unity, depicting the Indian politician and independence activist Sardar Patel, commissioned by Narendra Modi and completed in 2018. In conjunction with the Sardar Sarovar Dam, built to complement it, the statue left a trail of damage in the communities of the Narmada Valley. Kher’s colossal Intermediary Family (2018), built for the Frieze Fair at Regent’s Park, London, felt like a response and a protest. A huge, recomposed composite of gender-blended figures, it magnifies and celebrates the flawed, fractured, inherently plural character of ordinary humans, rather than smooth, monolithic figures of scripture, myth, or history.

In 2022, Kher installed the eighteen-foot Ancestor in New York’s Central Park, where it towered above one of the gates, a bronze every-mother clad in a sari, with twenty-four physiognomically diverse heads burgeoning from her torso. Another bold scaling up of the aesthetic of The Intermediaries, it is made of broken and found figurines that show the scars and cracks acquired in their journeys. The work organically codes the multiplicity, contradiction, and diachronic continuity of female fecundity and labor.

Placed in prominent Western public spaces, these gigantic re-assemblages assert the inextricable amalgam, the cultural braid, that India always has been. They challenge the current ethnonationalist drive to sift out strands, to “purify” India and present a homogeneous national identity to the world. This is art confronting artifice: acts of defiance and healing at once.

Repetition and Difference

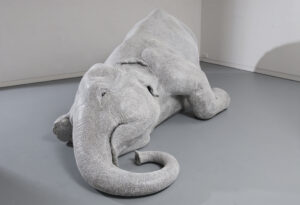

The monumental and the particulate come together spectacularly and movingly in Kher’s famous early work The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own (2006), a life-size fiberglass elephant that has fallen to its knees under its own weight. Its eyes glisten and plead; it appears to be dying. But its skin is made of a dense, endless web of white bindis in serpentine whorls that balance its gravity with a poignant grace. Drawing the eye closer, they incite engagement at a minute and animating level, an alternative to the distant Western view that exhausts the elephant-as well as its surrounding culture-by framing it as an icon of India.

Bharti Kher. The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own, 2006. Bindis on life-size fiberglass elephant. 58¼ x 170 x 72 inches.

Kher is drawn to paradox: her balance sculptures and “axis drawings” are an almost scientific probing of geometry in space. Triangles have a special place in her abstract work, sometimes commenting on the politics of space, such as geodesy and the Orientalist map-making undertaken by colonial powers. But it is the triangle’s role in her understanding of the poignant position of art between materiality and abstraction that I find most profound. Impossible Triangle (2012), for instance, presents a chair with a triangle suspended above it as though held by invisible strings, pushing material to its limit, and even beyond the possibility of Euclidean space. In her many works that seem to defy gravity, there is often a counterbalance, a hefty weight that betrays the price of crafting improbable lightness. She frequently declines the alleviating comfort of a circle and keeps returning to the bleak exhilaration of triangles, which, she writes in her diary, “have no inside or outside.”

The repetition of labor is, for Kher, a ceaseless search and a spiritual discipline. Her 2023 exhibition at the Arnolfini Centre for Contemporary Arts in Bristol, The Body Is a Place, was anchored by a mesmerizing centerpiece in the upper gallery: Consummate Joy and Sisyphean Task. The work embodies a delicate poise that could only come out of contradiction and fragility, achieved through the contrapuntal placement of contrasting textures and movements: arc against pendulum, suspension against gravitation, wood against stone, coarse against smooth, copper against steel. Its shapes are choreographed into a tense if dreamy ecology: circle, rectangle, cylinder, triangle. In Greek mythology, Sisyphus is condemned to roll a boulder up a hill only for it to roll down as soon as it nears the top. Kher rewrites the myth through the lens of Eastern spirituality. Her rock is a rich, red jasper, a precious and protective stone that refigures repetition as meditative ritual rather than punishment, and failure as the instrument of spiritual vigilance. But Camus would have understood it too: he concluded his famous essay on the myth by suggesting that “the struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Bharti Kher. Consummate Joy and Sisyphean Task, 2019. Wood, copper, steel, red jasper stone. 97¼ x 26⅓ x 78¾ inches. Photo: Ken Adlard.

The sense of the enigma and grace of accumulation also flows through a very different ongoing work, one that is quietly accretive in time: Virus (2010-39). At the Alchemies exhibition, the huge, site-specific Virus XV (2024) comprised a giant orange circle made up of thousands of infinitesimal bindis spiraling on canvas, bright as the sun at its rising, along with a text by Kher. Conceived as a cumulative thirty-year work exhibited annually at sites around the globe, the work evolves each year in the form of an expanding prophetic text about humanity’s future and the artist’s life. This slow repetition-with-difference is an apt metaphor for Kher’s own artistic evolution and cyclical leitmotifs. The subterranean consonance underlying her life’s work emerges slowly, demanding a minute, meditative attention and a deep intuition of correlation across disparate matter. It feels like a spiritual exercise: repetition not as compulsion but as release, and sometimes redemption.

Unheimlich Houses

For Kher, space is not just a medium; it is also a frequent subject. Deaf Room (2010-12) is a room-within-a-room made of ten tons of glass bangles melted into bricks. It is a somber monument to the massacres and sexual violence that accompanied the inter-communal riots in Gujarat in 2002. Traditionally worn by Indian women, cheap glass bangles chime joyfully in everyday life with the swaying of hands. The room figures the muting of that song as a haunting deafness, the grout between the bricks trickling in drips like slowly congealing blood. But it is also a space of meditation and elegy, a house whose meaning is conferred by the women who are not there. Horror and pain are transmuted into art, but without eliding the cost of transformation.

Bharti Kher. Deaf Room (detail), 2001-12. Glass bricks and clay. 5 x 95 x 95 inches. Photo: Jonty Wilde.

Deaf Room reminded me of one of her many other rooms, Confess (2009-10). After installing this square wooden structure at the Tate Modern for an exhibition in 2022, Kher learned that it was originally a South Indian matriarchal matrimonial chamber, a room in which a bride would be placed with all the worldly goods she was supposed to take into her new life. This enclosed, intricately carved space evokes intimacy while also underscoring the fine line between security and confinement, the authentic and the crafted, the voluntary and the enforced, the domestic and the institutional. Viewed from different angles, it morphs from confessional to bedroom to prison cell. In its multiple and contrary possibilities, it offers a metaphor for the mind, which can make a heaven of hell or a hell of heaven, liberating or incarcerating us.

For Kher, houses are fertile ground for the imagination. As Geoffrey Hill writes in “The Songbook of Sebastian Arrurruz,” “The metaphor holds; is a snug house.” It holds out against rain and storm, but it also holds in, containing contradictions. As the house-as-metaphor shades off into metaphor-as-house, Kher, an artist of intimate estrangements, makes these unheimlich homes breathe.

Casting the Body

Kher’s command of media is kaleidoscopic, ranging from drawing and painting to collage and sculpture. She makes use of brickwork, clay, metal, wood, wax, fabric, resin, glass, paper, and burlap. But plaster casting has a special significance for her, and no work illustrates this better than Six Women (2012-14): full-body casts of middle-aged sex workers from Sonagachi, the red-light district of Kolkata. I first encountered it in person at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park exhibition. There they were: life size, silent, meditative presences standing in for the absent women, witnessing and commanding the space. Even as I was riveted by Kher’s conversation with the curator taking place in the same room, I was all the while aware of these figures, who demanded both an intimacy of engagement and an acceptance of the unbridgeable distance between us.

The process of casting is curiously intimate-unmediated, as the body leaves its imprint on the plaster through touch. “Give me your essence and be light for that time,” Kher writes in her sketchbook about Six Women, apparently offering an exchange. Yet she writes elsewhere, “I can’t give you my essence, no matter how hard you try to take it.” She is ostensibly writing an Ovidian love letter to her notebook (“Heroides III”), but this tactile epistle, describing the “scratch,” “bite,” “sting,” and “cut” of her pencil lead on the paper, is really grappling with the endless wrestling match between matter and metaphysics in the practice of art; with the relation of longing, seizing, giving, and eluding between form and the object of its hunger. For isn’t casting a form of mendicancy too, begging for the gift of essence? And if a cast is a memory of the skin, is it not burdened by histories it cannot erase? Unlike most of her other casts-such as the bodies of her parents placed archly across Freud’s couch in This Breathing House (2016) or that of her friend in Warrior with Cloak and Shield (2008)-the models here are not her loved ones. She paid them to travel to Delhi and sit for her. Mimetic art wants to distill rather than replicate. Is the artist a consumer or empath, parasite or alchemist, as she intervenes in an economy of sex and money to draw from it? How does her own relation to the viewer map onto the relationship between her six subjects and herself as intermediary? And what is the relation of the “fallings from us, vanishings” (as Wordsworth calls them in “Ode: Intimations of Immortality”), the things we cast off and leave behind, to the art that puts them on? Is a cast an accident or an essence, residue or invention?What do Kher’s subjects grant? The six women expose themselves even as, with shut eyes, they resist revelation of their interiority at the very moment they intimate it. At that shimmering threshold between disclosure and withholding, inwardness acquires form, “acutest at its vanishing,” like Wallace Stevens’s sky in “The Idea of Order at Key West.” It is not knowledge so much as tenderness that gives the artist access to them and allows an elusive transfer. When first showing Six Women, Kher positioned the figures facing four spotted mirrors, actively courting such questions by evoking the paradigm of encounter. What does her art give back to its human subjects-wages or grace? The sense of confrontation in turn reanimates the simulacra of the women, locating them somewhere between flesh and glass.

The duality imposed by casting is opened up into a space for achieved wonder and serenity in the series Chimeras. Plaster casts of heads and faces are first coated with wax, then broken up to reveal layers of wax, burlap, and plaster. Here, too, this excavation of interiors does not lead to complete knowledge but to an encounter with the irreducible obscurity of our inner matter. The essence the caster seeks is both real and unyielding. But when the subject is the artist’s mother rather than unknown women being paid for a job, casting enacts a myth of origins, offering a path of return to the source through a formal matriliny. During an artist’s residency at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 2015, Kher was mesmerized by the death mask of Beethoven-which led to her turn toward casting. But if the death mask preserves the memory of the absent person through a vivid shadow of their living form, the head of the artist’s mother that we face in The Half-spectral Thing turns that presence inside out, taking us to the absence at the heart of the animate. Through an archaeology of the sources of the self, Kher uncovers its essential opacity.

The Mystery of Heart-Space

Her ceaseless search for the mystery at the heart of things-not to pluck it out but to apprehend and inhabit it-drives Kher to keep revisiting her jousts with risk, which are also leaps of faith. She batters things out of shape, squashes discrete objects together, prises wholes apart, smashes surfaces, flings things to the wind with reckless abandon, and watches to see what happens.

So she cast a figure from her mother’s body and threw it from a great height, inflicting an injury on form that paradoxically provided an occasion of hospitality-to chance, hazard, and grace. The fall cracked open the chest cavity-her mother’s heart-space-and preserved the rest intact. Kher gathered up the cracked figure and placed it with tenderness on a layered plinth. With equal tenderness and attunement, the late critic and curator Aveek Sen named it Pietà, noting the poignant inversion of the familiar Renaissance iconography of the young mother cradling her dead son. Here, it is the daughter whose shaping hands cradle the aging mother in her artwork.

There is violence in the act too. Kher tells me that she wanted to go inside her mother’s body again. But the maternal body prised open is the dream of home turned uncanny, a reframing of the sacred. Is the artist here a violent anatomist or a dispossessed refugee? Playing on the double sense of casting, she places her work between accident and essence, residue and invention.This Pietà is part of art’s endless grief work, as the daughter’s proleptic meditation on her mother’s mortality becomes a journey inward. Pristine as marble from a distance, the bed on which the eviscerated body rests turns out to be wax, receptive to warmth and pressure, gently holding her inner wilds. The fugitive synchrony between the chaos of human life and the equally human need to shape it grants Kher’s Pietà the condition of an elusive miracle. It is a luminous example of how art can lead us back to our own heart-space-Rilke’s herzraum, filled with holy absence. Amid the restless energy of Kher’s ever-morphing art, works such as Pietà find a stillness that offers a sanctuary-as if yearning for home can itself be a dwelling place.

Subha Mukherji was born and raised in Kolkata. She is professor of early modern literature and culture at the University of Cambridge. Her research interests include the interdisciplinary Renaissance, literature and knowledge, the poetics of space, migration studies, and contemporary Indian art.