WE ARRIVE AT THE DES MOINES PRIDE CENTER expecting a few boxes of discarded books. We do not expect a library, or the center’s president. She introduces us to the handful of volunteers who will help move fifteen hundred queer books to Iowa City: the treasurer, the archivist, and the archivist’s boyfriends; the boyfriends are the most enthusiastic about lifting boxes. If it does nothing else, polyamory moves libraries. Everyone pitches in to fit the library into a last-minute U-Haul rental.

Later, unpacking, Aiden and I realize how many times this library has been unpacked before. It is a compost pile of deaccessioned books from almost every queer community library in the Midwest. When queer books become unwanted, they are impossible to discard. Rather, they’re simply shipped to other queer libraries. The Stonewall National Museum & Archives even offers “LGBTQ Library Starter Kits,” mailing boxes of weeded books to seed new libraries. It’s standard practice for public libraries to offload their discards to other public libraries—or sell the books to the public. But weeding is different when a category of books is, as I believe Maggie Nelson puts it, “born endangered.” It is as if queer books sit outside the library at large. Do we sense, intuitively, that queer books are better off in their own company?

Since the day we acquired a queer library, I’ve come to think of the other library—the one where I work as a cataloger of artist books—as the straight library. Most of the artist books are also straight. In spite of this, their personalities are fine. Better, perhaps, than ordinary books.

Artist books are often positioned against the library at large, not as part of it: for example, in “The New Art of Making Books,” perhaps the most iconic manifesto about the book as medium, Ulises Carrión writes off “the books of bookstores and libraries” as “accidental receptacles of a text.”

Yet patterns surface in the artist books that cross my desk—enough to make cataloging possible. There are standard fields that apply to most artist books; in fact, artist books might fit comfortably in a handful of boxes.

Before writing “The New Art of Making Books,” Carrión gave away all the books he owned. In order to understand the book, he had to discard the library.

In order to understand the library, I wish to discard the book.

Consider that we didn’t have to read any books to move a library. And the volunteers at the pride center didn’t have to read any books to decide what to discard. They weeded any fiction older than 2010 and any nonfiction older than 2005—particularly any information about HIV, which would not be current.

The queer library must exist in the present.

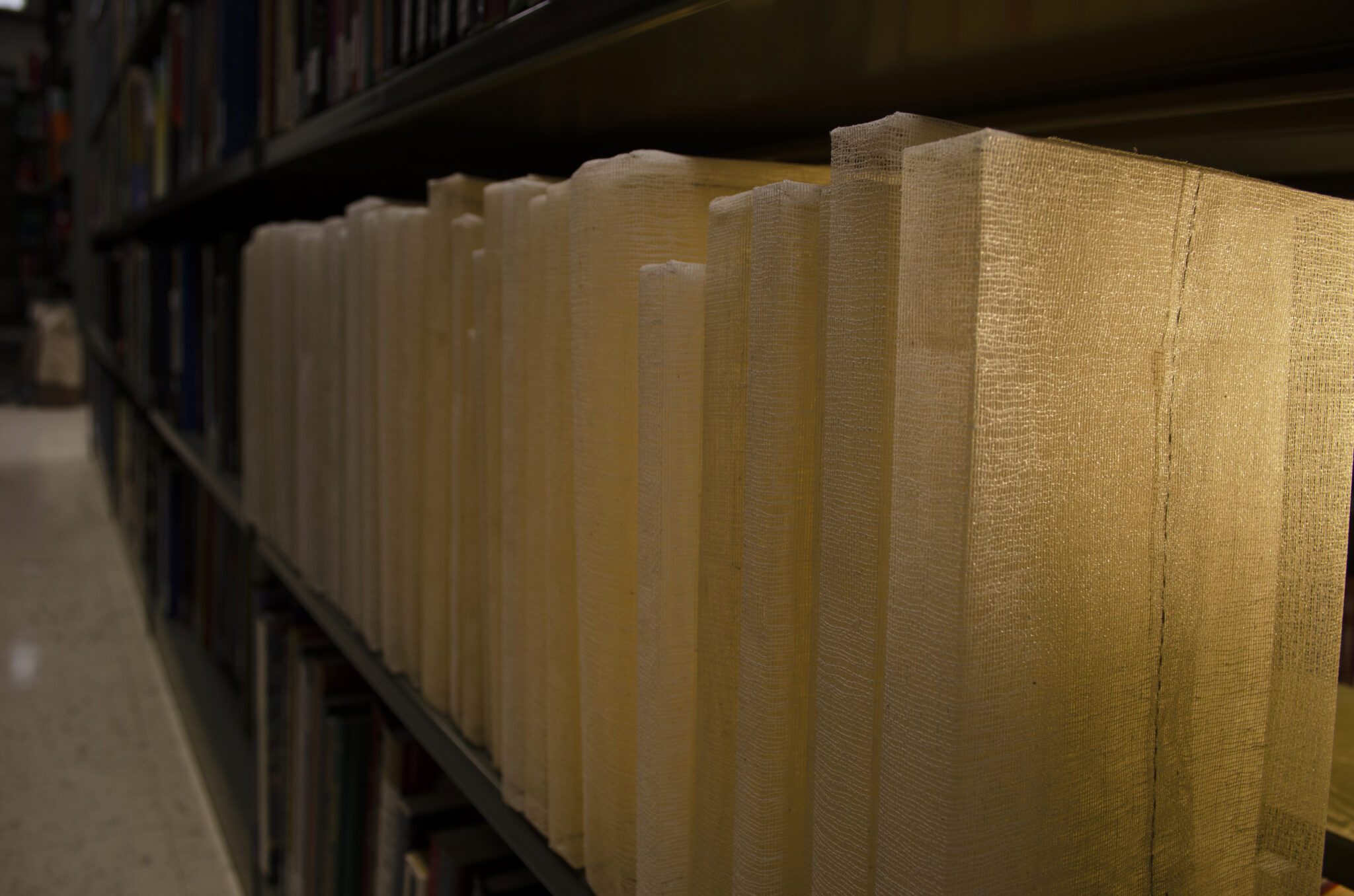

India Johnson. Negative Theology, 2019–20. Mull and silk thread. University of Iowa Main Library stacks. Site-specific installation. A shelf of books on theology and violence were checked out and cast in fabric. The fabric casts were then placed on the shelf until the original books were due a year later.

As the holidays approach, the books migrate from boxes to shelves. Aiden and I buy matching flannel shirts, force our cats into plaid bow ties, take a family picture in the snow, and mail it to everyone we know. Covid is a welcome excuse to spend our first Christmas together at home, in love, and completely alone. Earlier that year, after his top surgery, I’d moved into Aiden’s apartment for his recovery and never left. We’re happy in the crowded apartment, but space is so tight that, when I officially move in, I opt to unpack my books into my studio. The room is small, just six by eight feet, in the basement of a multipurpose building lined with identical rooms. Painted a medical shade of pistachio green, at one point my studio was an exam room at a free medical clinic, the first site to offer HIV/AIDS care in Iowa City. The landlord is a church that has just fired its pastor for officiating a lesbian wedding. The interim pastor seems a bit uncomfortable about leasing additional rooms to what will become LGBTQ Iowa Archives & Library, but we come to an understanding: the church needs tenants for the vacant basement as desparately as we need a place to unpack hundreds of lesbian romance novels.

With Buzz Spector’s artist book Unpacking My Library as a point of departure, I decide to document my personal library in terms of its weight and volume. I align the spines on my studio floor, ordering them by height alone. Like Spector, I unpack my library with the intention of fetishizing the book as object. Unlike Spector’s, my library is a queer library. Unlike the queer library being unpacked two doors down, my library is minimal. The collection weighs seventy-seven pounds and is roughly the height of my body.

When Ulises Carrión wrote “The New Art of Making Books,” his library weighed nothing.

I count the number of books in my library written by queer authors: just nine.

What kind of exhibition would Ulises Carrión curate in 2022? Would it even include artist books? A tragedy of the twenty-first century is that an artist like Carrión, who collapsed art and its distribution—experimenting with books, mail, audio, video, lectures, and even gossip as media for art—didn’t live to see TikTok. Carrión’s straight contemporaries, and the gay ones who survived a plague, his friends and collaborators, are by and large still alive. They defined independent art publishing as a field, and still do. I attend their conference presentations, follow them on Instagram, catalog their books at work.

Yet no artist publisher, living or dead, has been more important to my own work than Carrión. Of the nine books by queer authors in my personal library, four are his.

Jenn Shapland’s essay “Unpacking My Lesbian Library” conjures bookshelves crammed with lesbian authors: sorting her books after a move, she keeps Virginia Woolf, Jane Bowles, Carson McCullers, Susan Sontag, and “Djuna Barnes no matter what she said”—and of course Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, and Sappho. She chucks Hemingway and even some of the gays, like Burroughs: “Shoot your wife, get lost.”

An essay about one’s bookshelves should, like Shapland’s, showcase intellect and taste. Our hand-me-down queer library has neither. Sure, there are a few gems, like the lesbian parodies of James Bond and Nancy Drew, Jane Bond and Nancy Clue. Lesbian romance forms the bulk of the collection (Nuns and Mothers; Riverfinger Women; She Came Too Late: A Womansleuth Mystery), complimented by outdated gay science fiction (the 2069 trilogy, about anal sex with aliens), outdated gay nonfiction (Is the Homosexual My Neighbor? Revised and Updated), and outdated gay self-help (Men Are Pigs, but We Love Bacon). A few of the how-to books still seem relevant (Queer Astrology for Women, since for queer women there is no such thing as an out-of-date astrology book). One of the most useful books in the collection appears to be Hot! International Lesbian, which translates words like “dental dam” into seven languages. We joke about planning a reading of Best Lesbian Erotica 1997 in conjunction with Best Lesbian Erotica 1996. A volunteer points out that lesbian books are overrepresented in the collection. Her theory: unlike gay men, “lesbians actually read.”

We unbox multiple books about Grant Wood, who founded a gay art colony in Iowa, and plenty about gays and the church. Most of the nonfiction falls into two categories: sex (The Phallus in Fact, Fiction, and Fantasy) or god (The Lord Is My Shepherd and He Knows I’m Gay). There are a few books that aren’t worth cataloging, but we more or less decide to keep it all. In this library of discards, we will not weed.

Essays about unpacking libraries are actually about unpacking books. Shapland’s lesbian library is made of individual volumes, each of which has earned its place on the shelf. Our queer library’s volume matters more than any individual book. Why settle for queer books when you can have the library?

In recent years, there’s been a revival of interest in Ulises Carrión. His main translator, Heriberto Yépez, claims him as “the most innovative postliterary writer to be born in Mexico.” In the field of book art, Carrión’s theory and criticism are key texts. Unfortunately for queer book artists everywhere, most of the renewed global attention to Carrión does not acknowledge his sexuality.

Before it became a ghost, was Carrión’s library a queer library? Little of Carrión’s art or writing deals with his sexuality overtly or at all. One exception is a 1981 performance lecture, “Gossip, Scandal and Good Manners,” in which Carrión delivers a formal report on gossip he circulated about himself in the Amsterdam art world: that he had been married to a woman once; that she was now a dying nun; that she had come from Mexico to see him one last time. That his uncle in Mexico died and left him an inheritance. That his partner, Aart, went to Mexico to administer the estate.

Erasing queer artists’ queerness from the record may be so routine as to be unremarkable. I nonetheless feel personally robbed of all the art Carrión did not live to make. He once proclaimed that “art as a practice has been superseded by a more complex, more rigorous, and richer practice: culture. We’ve reached a privileged historical moment when keeping an archive can be an artwork.” But what happens when the archivist dies young? I feel robbed of Carrión’s Twitch channel, his TikTok videos, outraged that he died before his time. Why do no other texts about him share this outrage?

Among the fake gossip Carrión circulated about himself was that he would have a retrospective in a major museum. That he was dying from a rare cancer.

He died at forty-nine, of AIDS-related complications. Twenty-seven years later, he had his first retrospective—at the Reina Sofia, no less.

Unpacking a queer library into a basement is a granular, physical, and at times moldy task. Why did we go to so much trouble for a library that was, frankly, full of useless books? Unlike a private library, our collection wasn’t curated. Unlike a special collections library, it contained no rare or valuable books. Public libraries are driven by use; ours was driven by disuse.

To research this question, I cram a small library about libraries into our overstuffed apartment. I read about Walter Benjamin’s library, Edith Wharton’s library, Gloria Anzaldúa’s library. I read about lesbian feminist bookstores, freedom libraries, dynamic libraries where each book has a digital tag and no static place on the shelf. I read a directory of alternative libraries, published in the eighties, from A to Z. I read a textbook about cataloging, theory about artist book libraries, and a history of alphabetical order. I purchase a copy of Ulises Carrión’s artist book In Alphabetical Order, which takes a playful approach to information systems: “The real fact is that I love lists of names, card indexes, information retrieval systems, that sort of thing.” The acquisition bumps the total number of queer books in my personal library from nine to ten.

Finally, in a study of the libraries birthed by the Occupy movement, Sherrin Frances describes the first library that sounds anything like the library we have been given: a protest library. A library where discarded books are welcomed, take up space, and grow. Just a few books can catalyze a protest library, because they will attract more books. If a protest library was a plant, it would be a weed; a spontaneous being that reproduces itself. Frances claims that most protest libraries share the same origin story: “a pile of books appearing and becoming a library, suddenly and without much human intervention.”

Protest libraries, writes Frances, emerge from “prefigurative politics, which generally means an attempt to create right here and now the kind of world we want to live in, rather than setting that world as an idealized goal and working to achieve it in the near (or distant) future.” The queer library must exist in the present.

Before he moved to Europe, Carrión worked as a librarian in Casa del Lago in Mexico City. It’s hard to read a paragraph about Jorge Luís Borges without being reminded he was a librarian. But what if proximity to a library leads you to make not texts (like Borges) but books (like Carrión)? What if the books, suddenly and without much human intervention, reproduce? Library as dandelion.

After Christmas, after months of unpacking and cataloging books, the library collective opens the doors to LGBTQ Iowa Archives & Library. At the opening party, Lizzo reverberates in the stacks; masked volunteers dance six feet apart. Almost as soon as the library officially opens, the bubble bursts: the Iowa State Legislature goes into session for the year, proposing fifteen anti-LGBTQ bills over two months. The library frantically publishes a subject guide to the torrent of anti-trans legislation.

“Why libraries at all when there was so much other work to be done?” asks Frances. “Why put so much effort into an aspect of the camp that had no direct impact on the protest, something that was only obliquely related to the main purpose of the resistance activities?” Why does queer liberation need queer libraries when it needs so many other things first?

A month after the library opens, at 5:30 on a Saturday morning, Aiden and I stop to pick up Heather, who is waiting on the porch of her housing collective in a floor-length fur coat, smoking. Outside the library, we join a fleet of nice Subarus and four-door beaters. Library volunteers huddle as the sun rises. Aiden goes over the plan (to disrupt a town hall for State Representative Sandy Salmon) and the route (which includes a stop at Casey’s for doughnuts, coffee, Red Bull, and gas).

How many straight Iowans will drive to the middle of nowhere to talk to a state legislator about bathrooms? Reader, the answer is zero. It’s tense as the caravan of visibly queer and trans people pulls up at the community center in Denver, Iowa. My lavender Carhartt vest feels especially protective as I exit the Subaru. Every other queer in the caravan also conforms to the Carhartt-and-beanie stereotype, except for Heather, who is dressed for battle: snowbanks are no match for her strappy high-heeled sandals. She’s accessorized the fur coat ensemble with an oversized pink purse and a two-liter bottle of Mountain Dew.

We march into the community room, past all the locals waiting for the meeting to start, and occupy the first row of chairs. The library collective is here to be a nuisance, to take up as much of the meeting time and space as we can. As trans Iowans describe how her bathroom bill dehumanizes them, it becomes clear that trans people are mostly an abstraction for Sandy Salmon, who stumbles over relevant vocabulary like “dysphoria.” One of her bills will treat doctors who provide gender-affirming care as criminals; she argues that hormone-replacement therapy is a vice, akin to alcohol and cigarettes. The locals want to talk about schools and potholes; we hold the floor as long as possible.

On the drive home, the library’s associate director, a butch theater dyke, googles how much it would cost to rent a porta-potty. Her idea is to install it on Sandy Salmon’s lawn, label it “gender-neutral bathroom,” and invite every Iowa queer we know to take a shit.

Shitting in Sandy Salmon’s front yard proves unnecessary; that year, none of the fifteen bills passes. The next winter, the Iowa State Legislature proposes twenty-seven anti-LGBTQ bills and finally manages to pass one. Our queer community library celebrates its first anniversary.

In 1975, Carrión opened the first artist book bookstore: Other Books and So (OBAS) was located in a basement in Amsterdam. Carrión crowdfunded OBAS through his mail art network (what could the man have accomplished with Kickstarter?), announcing it as a space for

other books concrete books multiples

non books conceptual books posters

anti books structural books postcards

pseudo books project books records

quasi books plain books cassettes

After four years in business and two moves, Carrión closed the doors of his bookshop. Other Books and So became a publicly accessible archive at 121 Bloemgracht in Amsterdam. Joan Lyons called it the picture of a “real” archive: highly organized and “perfect.” Carrión welcomed visitors until his death in 1989, snapping a polaroid of each one for the guest book. At what point during the AIDS crisis did Carrión sense that his archive would outlive the archivist? Given Carrión’s prolific output, meticulously archived by the artist himself, why do I insist on dwelling, instead, on his biography?

Carrión was a gay artist who died young precisely because he was gay; shouldn’t there be at least one account of his life that finds this consequential? Maybe I’ve spent too many weekends talking queer elders into donating their papers to LGBTQ Iowa Archives & Library. Recently, an aging lesbian gave us copies of the folk album she recorded with an all-lesbian band, along with a scrapbook kept by her friend Tracy—the first man in Iowa to apply for a same-sex marriage license. She included some photos too: snapshots of Tracy’s drag outfits, weekends spent in bars and diners with friends. His obituary. On the shelf next to Tracy’s scrapbook is an archive box stuffed with a lifetime of love letters. On Thursdays, their white-haired recipient runs a program at the library called “Astrology with Craig,” which is just what it sounds like. Judging from the archive, some of Craig’s lovers wrote to him almost every day. How many died before the peak of the AIDS crisis, when the members of the library collective were toddlers? Carrión’s partner, Aart, outlived him by a year and a month.

A year after opening, the queer community library finds better real estate. It will move into a historic house with two other local orgs: the Center for Afrofuturist Studies and Public Space One. In the past year, the collection has swollen. It is both larger and better than the library we inherited. When there is money, we prioritize buying books for kids, trans books, and books by queer and trans authors of color. Community members donate books and bookshelves. Our volunteers take an inventory of the books in preparation for the move. Every book will need to be packed, carried up the basement stairs, driven a few blocks, lugged up two flights of a spiral staircase in a Victorian mansion, unpacked, and shelved. Out of curiosity, I calculate the total weight of our collection. We prepare to pack and unpack a library that now weighs 2,157.8 pounds.

Frances reminds us that “the sheer brute force that it takes to move even a few hundred books is obvious…. Material book collections in protest libraries almost sound like an amenity, even a luxury, because they require so much ongoing attention and labor.” Still, “the attention demanded by a large quantity of material books is not only not a detriment, it is actually an asset. The physical properties are precisely the thing that defines the books’ worth, calls the space of the library into being, and generates a drive that literally pulls people off course and attracts more and more books.” In other words, once you set a queer library in motion, more lesbian fiction will materialize.

One Saturday, the team of core library volunteers rallies to extract eight hundred lesbian romance novels from a basement in North Liberty, Iowa. There are reasons you might not want to own a single Karin Kallmaker novel but would want to own all forty-two of them. As Pierre Bayard puts it in How to Talk about Books You Haven’t Read, “being cultivated is a matter not of having read any book in particular, but of being able to find your bearings within books as a system and to be able to locate each element in relation to the others. The interior of the book is less important than its exterior, since what counts in a book is the books alongside it.”

In other words, just as texts don’t exist in a vacuum, neither do books.

If Benjamin is right when he claims that “ownership is the most intimate relationship we can have to objects,” nonreading is the most intimate relationship we can have to books.

Nonreading is the only way to read the library.

This makes the library a reading method.

The library’s longest-running and most popular program is an intergenerational craft circle for all genders. One Monday night, I’m in charge of setting up the space for Queer Threads. Queers trickle into the library with their projects: crochet, upcycling, costumes, quilts. The conversation is a simmering alphabet soup: SCA, D&D, HRT leading to 34DD. Crafters stitch and topics drift: gender-expansive sewing patterns, why kink (but not cops) belongs at Pride, cross-stitch, League of Legends. Most of the crafters are young enough to make me feel old. As gaming begins to dominate the chatter, I’m grateful when Cara, another thirtysomething grandmillenial, shows up to tie a quilt. Cara’s powerclashing patchwork is incredibly precise; her quilts look like Martha Stewart joined a roller derby team.

I drag her to the cataloging pile and pull out a recent donation: “You have to see these new books.” Cara can barely contain herself: Gay Sleeping Arrangements: Patchwork Quilts for Men Who Love Men and Queer Quilting: Patchwork Designs for Gay Men contain at least a hundred phallic quilt designs apiece. She snaps a few photos, and we talk about raffling off a quilt with a nice symmetrical layout (four dicks and one asshole) for the library’s benefit.

These pattern books are self-published by a gay ex-Mormon author named Johnny Townsend. When he heard about our library, Townsend mailed us ten dollars and a handful of his books, including his new novel, Orgy at the STD Clinic. Strangers often send books and money: once, a girl scout troop in central Iowa found us on TikTok and mailed a check for $350.

Like most radical libraries, we don’t turn down donations. Protest libraries tend to be built “solely on remainders and excesses from other collections,” Frances writes. As a result, they are “not inclined toward exclusion. The protest library is driven by the collection, a glaring inversion of the usual model of library building.” Someday, I hope the library dedicates an entire shelf to Townsend’s strange, extensive bibliography: Zombies for Jesus, Dragons of the Book of Mormon, The Gay Mormon Quilters Club, Who Invited You to the Orgy?, Sex on the Sabbath, Dinosaur Perversions, Blessed Are the Firefighters, Gayrabian Knights, Strangers with Benefits.

One reason protest libraries provoke spontaneous donations is that, according to Frances, “the idea of a library, its essence, seems indisputably positive. In all the research I have done on libraries around the world, I have yet to find anything arguing against the concept of a library. Libraries, both public and protest, are just very simply good,” and people intuitively grasp their virtues. But straight libraries and queer libraries have different priorities. More or less, the first four laws of library science guide the straight library:

Libraries are for use.

Every book its reader.

Every reader their book.

Save the time of the reader.

In contrast, the books of our queer library are rarely read but lovingly kept; nothing about the maintenance of the collection is efficient. Instead, queer libraries epitomize the fifth law of library science:

A library is a growing organism.

Books with what Francois Deschamps calls the “survivability strategy” of weeds. Library as protest, vigil, and knitting circle. As Carrión speculated, “a book is a volume in space.” The queer library is best understood as a critical mass—no more, no less.

India Johnson received an MFA in book art from the University of Iowa, makes installations and participatory projects in and about libraries—most recently Thread Library (threadlibrary.omeka.net)—and is a founding member of LGBTQ Iowa Archives & Library.