WHEN MEASURING an artist’s greatness within a particular tradition, the essential criterion is not what that artist takes from the tradition but what he or she adds to it. For almost half a century, Gerhard Richter has applied his creative aptitude and technical facility to a critical investigation of the viability of a genuinely contemporary method of painting in an age of digital reproducibility and artificial intelligence. In the process, Richter has produced conceptually challenging and aesthetically elegant paintings that substantiate and even expand the human impulse to hope. If modernism was an age of reason, its demise inaugurated a wave of cynicism, which Richter finds creatively untenable. Confronting critics who would disavow painting as a realization of faith, he developed a strategy of expectant skepticism.

Although it has often been ignored in scholarly discussions of his work, a spiritual current runs through Richter’s art. This enterprise is diversely manifested in his romantic landscapes and seascapes, ethereal abstractions, haunted still-lives of candles and skulls [see front cover], and several works with more overtly Christian subjects. Few artists have been more persistent in raising issues of faith and doubt in an art world that challenges many of the presuppositions of both religion and art. For his dedication, Richter was rewarded with one of the most important commissions in the recent history of Christianity and the visual arts: In 2007, he unveiled a new stained-glass window for the south transept of Cologne Cathedral [see Plates 5 and 6]. This is a work of such public prominence (and controversy), artistic accomplishment, and religious content that it has impelled even critics predisposed against Christianity and/or contemporary art to wonder if we are not witnessing the reemergence of an authentically contemporary art that is distinctly Christian.

Cologne Cathedral is a premier example of German Gothic architecture. Construction began in 1248 and was completed, after several interruptions but still according to the original designs, during the Gothic revival of the nineteenth century. One of the top tourist destinations in Germany, it is a unesco World Heritage Site. Cologne Cathedral is a unified artwork of religious, historical, cultural, and national significance. This overlay of sacred and secular needed to be taken into consideration in the commissioning of a new stained-glass window for the cathedral.

In 2003, cathedral master builder Barbara Schock-Werner was charged with overseeing the replacement of a window in the south transept that had been destroyed in the Second World War. During the war, the most valuable windows were secured in storage, and the remaining windows were blown out by the air pressure of aerial bombing. The cathedral itself was hit at least seventy times but did not entirely collapse and, as one of the few standing structures in Cologne, became a symbol of German rebirth. In 1948, the lost windows were replaced with clear glass. Since the war, the cathedral has steadily been restored, and in 2003 the time to replace the south transept window had arrived. Surviving black-and-white photographs show that the original window, designed in 1863, depicted several secular and ecclesiastical leaders. Because its designs were lost to fire, the decision was made to commission an original window by a contemporary artist.

Gerhard Richter, despite being one of the most celebrated living artists in Germany, may have initially seemed an unusual choice for such a prominent work of contemporary religious art. Richter is adamantly agnostic. He is also agnostic in an artistic sense, said to vacillate between faith and doubt in painting’s capacity to realize meaning beyond itself. However, if one looks at Richter’s spiritual and artistic life as a pilgrimage, rather than extracting quotations (some nearly fifty years old) out of context, an argument could be made that this Cologne commission represents the fulfillment of a long personal journey.

Richter has lived in Cologne since 1998 and has strong family connections to its cathedral. Three of his children were baptized there, and two sing in its choir. Describing the baptisms, Richter said in 2004, “my attitude toward the church had already radically changed, and I had slowly begun to realize what the church can offer, how much meaning it can convey, how much help, how much comfort and security.”

His book Gerhard Richter: Writings 1961-2007 evidences a forty-six-year trajectory of slow-growing sympathy toward Christianity. “By the age of sixteen or seventeen I was absolutely clear that there is no God,” he told one interviewer, “an alarming discovery for me, after my Christian upbringing.... By that time, my fundamental aversion to all beliefs and ideologies was fully developed.” After experiencing Nazism as a child and Communism as a young adult, Richter had become “allergic to ideologies.”

Having rejected all dogma, Richter directed his longing for faith into his art. In an early statement dated 1964-1965, in his early thirties, he wrote:

Art is not a substitute religion: it is a religion.... This does not mean that art has turned into something like the church and has taken over its functions (education, instruction, interpretation, provision of meaning). But the church is no longer adequate as a means of affording experience of the transcendental, and making religion real—and so art has been transformed from a means into the sole provider of religion.

In 1988, Richter reiterated this sentiment: “Art is the pure realization of religious feeling, capacity for faith, longing for God.... The ability to believe is our most outstanding quality, and only art adequately translates it into reality. But when we assuage our need for faith with an ideology, we court disaster.”

A 1998 interview with Mark Rosenthal demonstrates a softening towards Christianity. Discussing Mark Rothko’s art viewed through the prism of Robert Rosenblum’s landmark book Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: From Friedrich to Rothko, Richter said, “I’m less antagonistic to ‘the holy,’ to the spiritual experience, these days.”

By 2004, Richter was able to say, “I sympathize with the Catholic Church. I can’t believe in God, but I think that the Catholic Church is marvelous.” That he has more faith in organized religion than in the divine seems curiously opposite of many artists, who embrace personal faith while sidestepping its specific institutional realization. His affinity for the church may be as a site of prophetic inquiry and expectant longing. Furthermore, Richter has admitted that some of his past statements of doubt (in both God and art) were intentionally “polemical” and designed to provoke inquiry. He added that some of these were, “self-protective statements, designed to create a climate in which I could paint as I wanted.” In other words, by remaining noncommittal in his statements, Richter gained permission to create paintings, such as Sea and Skull with Candle, that are unabashedly spiritual. The question remains open whether Richter may still be using his provocative or oblique statements, which he knows will be used to critique his work, as a means of pushing viewers to engage the art through the prism of their own faith commitments rather than his.

Richter has said, “Strange though this may sound, not knowing where one is going...reveals the greatest possible faith and optimism, as against collective security.... To believe, one must have lost God: to paint, one must have lost art.” It seems that Richter is thinking of “God” and “art” as abstract dogmas, the result of groupthink ideology rather than as a personal being. He is opposed to any such weltanschauung. Without accepting certainty as an inherited truth, Richter employs what I would call an expectant skepticism as a strategy of realizing a more substantive certainty. Richter begins from a point of uncertainty, an attitude to religion that is the inverse of, for example, Bill Viola’s. Viola’s salad-bar approach to world religions is open to a little bit of everything (except the exclusive claims of Christ) and creates an art that suggests the presence of religious commitments without actually committing to them. Richter doubts everything but is certain that his work belongs exclusively within the Catholic tradition of art. Richter’s skepticism is not cynical. Remaining open to a form of belief, and strategies of creating forms of belief, Richter practices a via negativa, or via dubia.

Looking at Richter’s art chronologically, specific themes emerge, such as a sacramental, yet questioning, approach to the world of appearances. Several works suggest not only an openness to religious experience, but also a commitment to finding creative strategies of realizing those experiences in art.

Richter’s expectant skepticism is evident in a 1973 series of five paintings each entitled Annunciation after Titian. After seeing Titian’s Annunciation (c.1540) in Venice, Richter began to make a copy, working from a postcard. He did it, he says, “so that I could have a beautiful painting at home and with it a piece of that period, all that potential beauty and sublimity.” But his interest was more than that, I would argue. The angel’s annunciation to Mary of the birth of the Messiah occurs at the end of a long period of divine silence and human uncertainty. As a moment of conception in which expectations are realized, the subject of Titian’s work has parallels with Richter’s method. Having finished one copy, Richter recognized something in that work that lead him to make four more.

Plate 7. Gerhard Richter. Annunciation after Titian, 1973. Oil on linen. 49 x 79 inches. Courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC. Joseph H. Hirshhorn Purchase Fund.

The first copy most closely resembles its prototype, with some notable differences, however [see Plate 7]. Some of the edges of Titian’s composition have been trimmed. It is not clear if this was done by Richter or was the chance result of the postcard. Either way, the effect is that we are drawn closer to the annunciation. In Titian’s painting, the floor’s grid pattern delineates a pictorial system of representation that allows viewers to measure their distance from the action. Titian has also placed a column at the composition’s right foreground, which reminds us that we belong outside of the sacred space. Richter’s composition, as well as his strategy of softening each form’s edges, minimizes both the grid and the column.

In the four later copies, Richter transforms Titian’s Annunciation to the point that we might not immediately recognize it. Titian’s angel stands on a cloud of mystery. In some of Richter’s copies, this cloud seems to overtake the entire painting. Robert Storr writes, “Richter...looked at Titian’s Annunciation ‘as through a glass darkly,’ and we, looking over his shoulder, contemplate the once radiant masterpiece in the same smudged lens.” Blurring is only a negative gesture, one that obscures, if we assume that the goal of painting is clarity of representation. If the goal of painting is to incarnate the invisible in the visible (visible as distinct from the pictorial), Richter’s painterly treatment of the image may be part of a multifaceted strategy of revelation which distills Titian’s Annunciation to an encounter, a closeness, between areas of light, form, and substance.

Richter himself defends abstract art as a strategy of painting the infinite:

Abstract pictures...make visible a reality that we can neither see nor describe, but whose existence we can postulate. We denote this reality in negative terms: the unknown, the incomprehensible, the infinite. And for thousands of years we have been depicting it through surrogate images such as heaven and hell, gods and devils. In abstract painting we have found a better way of gaining access to the unvisualizable, the incomprehensible.... Art is the highest form of hope.

In the more “abstract” versions of Richter’s Annunciation after Titian, we are drawn to the essential movement of light that resolves, not dissolves, Gabriel and Mary. As the foreground, background, and most other references to pictorial space coalesce, Gabriel and Mary no longer exist in the world of the picture and instead become drawn into the painting’s material surface. Titian may clearly depict the story of the annunciation; however, Richter’s copies incarnate the “religious feeling” of immanence.

Plate 8. Gerhard Richter. Reader, 1994. Oil on canvas. 28 ¼ x 40 inches. Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Richter has said, “The central problem in my painting is light.” These works after Titian participate in one of Richter’s principal themes, the metamorphic effect of light, most often from an unseen source outside of the painting, diffused throughout a space which transforms objects from mundane to sacred. This strategy is particularly evident in works such as Cathedral Corner and Reader. Reader depicts Sabine Mortiz, Richter’s wife [see Plate 8]. The reader’s face is cast in a soft shadow that cuts across her ear and neck. The light, which seems to be coming from behind her, brightly illuminates the text that she holds.

Reader was painted in 1994. The following year, Richter painted a series of eight works entitled S with Child, depicting Sabine with their newborn son Mortiz, which have been often compared to images of the Madonna and Christ Child. It is not clear from Reader whether Sabine was pregnant at the time the work was painted, but if so, this would further connect it with traditional images of the annunciation, such as Titian’s, in which Mary is shown reading. The act of reading is an absorbing one, in which the reader takes the word into herself. Whether we regard this process of absorption, or Richter’s depiction of it, as mundane or miraculous is a test of our own faith. Artists have depicted Mary reading as a visual means of suggesting the virgin’s conception of Christ, the Word of God: words enter the body without wounding the eye. It is possible that here Richter is returning to the annunciation theme he had tackled, via Titian, two decades previously.

The background of Reader is not distinct, but at the left there seems to be a doorway, another motif common in annunciations. In many works, either Gabriel or Mary stands framed in the doorway as a way of separating the two figures and suggesting the incarnation as the crossing of a threshold. In Reader, the reading material, the word, is situated between the door and the reader. What is missing is the angel. Following Titian’s composition, Gabriel could be outside the frame, or it could be that Richter finds the angel unnecessary, or impossible to depict.

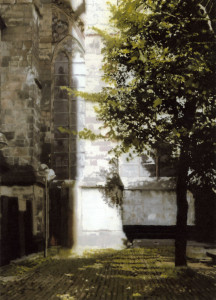

The evolution of Richter’s attitude toward Christianity is also evident in Cathedral Corner, a 1987 painting based on his own 1984 photograph of Cologne Cathedral [see Plate 9]. Cathedral Corner is a revelation of one of the cathedral’s buttresses caught in a moment of brilliant light, as the shadow cast by part of the larger structure has either just passed or is about to overtake the buttress. The theme of this work is the exchange between the transitory and the permanent—and the painting not only reveals that overlay but trains the viewer to see it everywhere. The exchange in Cathedral Corner is between the light, which is immaterial, and the cathedral, which is material. Light carries associations of natural processes and the spiritual; the cathedral is a monument of religious and cultural order. The work poses a number of questions: Is the light transitory, as we experience it, or permanent? Is the cathedral, which has stood for centuries, transitory? What can we know or trust of the world of appearances? By causing us to doubt the presuppositions that we bring to such a work, at least for a moment, Richter broadens our capacity to see.

Two decades later, Richter returned to some of these same themes in his window for the cathedral—with at least one notable difference. In Cathedral Corner Richter situates himself outside of the church. His focus on the buttress is telling. Richter’s process of painting is a search for reinforcement against his doubts concerning art and religion. Just as the engineering innovation of the buttress transformed Gothic architecture and made majestic stained-glass windows possible, Cathedral Corner buttresses Richter’s expectant skepticism, the attitude that made his window for Cologne Cathedral viable. Richter has evidently become comfortable inside the church. (In 1998, the year Richter made Cologne his home, he produced an offset print based on Cathedral Corner and donated the proceedings to the cathedral’s rebuilding fund.)

In 1996, he produced Cross using the proportions of his own height and arm span. (This rare example of sculpture by Richter is an editioned work that exists in both silver and gold.) “I tried to make it my shape. It’s not everybody’s shape,” Richter said. Here Richter moves from a theoretical, ideological, conception of the cross as a religious symbol, one largely drained of meaning in our culture, to a more personally significant form. He described Cross as “meant to be a bit polemical,” adding, “of course, it’s a symbolic gesture expressing the highest respect for our Christian culture, which stretches back two thousand years.” In Cross, Richter is personally identifying with Christianity and Christ. “That’s my home, those are my roots, it’s a tradition I have the highest regard for and which is far more complex than its critics could ever fathom. [My gold] cross coincided with the banning of crucifixes in [German] schools, which provoked a desire on my part to protest against the ruling.”

The Cologne Cathedral window was not Richter’s first church commission. In 1997, architect Renzo Piano invited Richter to participate in a church that he was designing for a pilgrimage site at San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy, in honor of Saint Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, a twentieth-century stigmatic. In a 2001 interview, Richter said he was interested in the project because, “I sympathize with Catholicism, without being a Catholic myself.” When Richter was asked to produce a series of figurative paintings related to the life of Padre Pio, he immediately informed the commissioning committee, composed of Piano as well as representatives from both the Franciscan Order and the Vatican, that he did not think he could “succeed” in filling that commission. Instead, Richter produced a sequence of six rhombus-shaped red-orange abstract paintings that had “a religious feel to them.” (Richter has dismissed suggestions that these paintings represented Pio’s stigmata, saying, “I can’t paint bleeding wounds.”) These works were rejected by the Vatican, but perhaps providentially were acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, only one mile away from the Rothko Chapel.

Richter’s experiences with the church have not all been negative, however. In 2004, he was given the Art and Culture Prize of the German Catholic Church by the Central Committee of German Catholics, a national organization of religious and lay cultural leaders founded in 1848. At the award ceremony, Bishop Friedhelm Hofmann said, “For many people, Gerhard Richter’s work has been and will be a spiritual experience.” This award roughly coincided with Richter’s acceptance of the Cologne Cathedral commission and marks a decided turn in his personal and artistic relationship to the church.

The initial Cologne Cathedral commission was for a figural design representing six twentieth-century Catholic martyrs: Edith Stein, Rupert Mayer, Karl Leisner, Bernhard Lichtenberg, Nikolaus Gross, and Maximilian Kolbe. “I was, of course, very touched to have such an honor bestowed upon me, but I soon realized that I wasn’t at all qualified for the task,” Richter said. As he began working from photographs of Nazi victim executions, Richter came to believe that this approach was failing the project on several levels. First of all, in an age of photography and the internet, we can know what these modern martyrs looked like. Depicting them like medieval saints elongated in the window’s height of nearly sixty-three feet would have oddly distorted them. Furthermore, Richter felt that depicting Nazi victims in a medium reliant on brilliant light was inappropriate. For both formal and thematic reasons, Richter began to lose confidence in his ability to realize the commission.

“After several unsuccessful attempts to come to grips with the subject, [I was] prepared to finally concede failure,” he wrote. However, fortune intervened. “I happened upon a large representation of my [1974] painting 4,096 Colors.... I put the template for the window design over it and saw that this was the only possibility. I wrote to the master builder, telling her that I wouldn’t be able to realize the suggestions made by the cathedral chapter, but that I would send her a draft anyway—one that, to me, seemed like the only viable way to design the window.”

4,096 Colors is the most visually complex of Richter’s “color chart” paintings, a series he initially created using hardware-store color charts. This strategy minimized the colors’ values associatively (blue is the color of the sky), symbolically (blue is the color of heaven), and pictorially (blue is a color that recedes from the picture plane), instead reducing color to its bare material essence as a form of visual information that can be calculated and quantified (blue A is darker than blue B but lighter than blue C and has more cobalt than blue D). As the color chart series evolved, Richter complicated his project by increasing the number of colors used and incorporating chance in the final design. Finally, he arrived at a system of multiplying specific colors and values that gave him an equilibrium of structure and accident. Stripping color of its associative qualities and aura in his color charts allowed Richter, thirty years later, to realize in his Cologne Cathedral window a sacred experience that is less entangled in received religious and artistic clichés.

The Cologne Cathedral window significantly complicated 4,096 Colors both conceptually and aesthetically. It is composed of 11,500 squares of blown glass, each nearly four by four inches. Richter employed seventy-two colors (eighteen permutations each of red, yellow, blue, and green) that were already present in the cathedral’s other windows. He eliminated indecipherable colors that he considered either too close to be distinguished or so pale as to be blinding when illuminated. In fact, there were many more variations in the other windows, since the manually crafted glass contains significant natural aberrations. The blown glass’s undulating texture naturally refracts and palpitates light. The total effect is one of resplendence.

Although Richter donated his time and design, about five hundred thousand dollars in public donations had to be raised to create and install the window. The cathedral initiated a campaign introducing Richter’s design to the public, and more than a thousand individuals donated to the project—a strong public endorsement.

To organize seventy-two unique colors into a design of 11,500 squares, Richter employed a computer program that designed half of each of the window’s sections by chance, and then mirrored that design in the other half. (He ran the program thirty-six times before arriving at a treatment that he liked.) This use of chance minimized the human inclination toward repetition and patterning that might, even unconsciously, enter into such a complex design. (In fact, Richter rearranged a few squares in his final choice in order to remove a numeral one that had inserted itself into the design.) Richter’s decision to mirror parts of the design was, then, an intentional reassertion of balance.

Although the grid structure gives the window a sense of higher order, the overall composition feels organic. As with the color chart paintings, the window’s colors do not read metaphorically or symbolically; it makes no pictorial references to anything outside of itself. (Perhaps because we know that the window was designed in part by a computer, there is a temptation to read it as the pixels of a digital image that is too large to be contained in the church or seen by human vision. Richter would undoubtedly dismiss this reading.)

Richter’s window is modern but not modernist; nor is it postmodernist. He demonstrates a critical knowledge of modernism without being indebted to its goals or prejudices. In fact, he participates in a premodernist conception of form. Before the Age of Reason, mathematics and geometry were regarded as a reflection of a divine mind, and particular sequences and harmonies were regarded as holy. This conception of sacred geometry was foundational to the design of the Gothic cathedral and its windows, and undergirds Richter’s use of chance in this commission.

The German word zufall means both chance and fortuity. Richter established a system and then allowed the process to unfold organically, with some intervention, within those parameters. Richter called this schema “very well planned spontaneity.” “It’s never blind chance: it’s a chance that is always planned, but always surprising.... I’m often astonished to find how much better chance is than I am.” Father Friedhelm Mennekes, director of Kunst-Station Sankt Peter, one of the principal exhibition spaces for contemporary sacred art, described Richter’s use of the computer as a higher form of intelligence, “an artistic gesture of humility.” As part of his method of expectant uncertainty, Richter employs chance as a tool with which to master ineptitude and doubt. For Richter, both doubt and chance are positive forces that participate in defining, solidifying, and even expanding the parameters of belief. Birgit Pelzer notes:

If doubt runs through [Richter’s] work, if he uses it, engages it, it is also because of the anticipation of a certainty. What is the basis of certainty?... If the artist grants this time of uncertainty, if he authorizes recourse to chance in its production, it is because he is magnetized by the conviction that something will come and stabilize and condense itself.

The work of art becomes both the agent and site of this condensation of doubt into belief.

Applied to this holy commission, Richter’s use of chance raises the question of whether or not chance inherently contains a divinely designed order. If the colors are organized indeterminately, are there not, nevertheless, rules and parameters to this process?

Sea is a collage that seams together two photographs of the ocean (one of them inverted) so that they touch at the horizon [see Plate 10]. Each implies the presence of an invisible sun. The work suggests that Richter sees the presence of a yet-to-be-revealed harmony that lies behind the world of appearances. However, because human fallibility distorts our conception of order into something to be imposed on nature, any human attempt at order or truth will inevitably result in violence. (Richter twice experienced the horrors of imposed “utopia,” under Nazism and communism.) Chance is an open and organic means of drawing out this invisible order from nature in a way that is free of human fallibility. In a sermon delivered at the window’s installation service in 2007, cathedral prelate Josef Sauerborn noted, “In chance, the unexpected and unforeseen is hidden. Chance becomes a cipher for the mysterious that transcends our mental capacity.” He added, “God is not computable; he cannot be contained in any system.”

While much of the discussion of Richter’s window has focused on its design and process, the work’s breathtaking effect is ultimately realized in the context of the cathedral. In fact, the window now seems like an inseparable part of the structure. Barbara Schock-Werner has said that the window “looks like it has always been here.” Within the architecture, Richter’s design is at once fixed and moving, expanding and framed. A magnificent Gothic work, Cologne Cathedral might have aesthetically overwhelmed many window designs. Conversely, an artist might have introduced a design that called excessive attention to itself in an effort to contend with the cathedral’s volume. Richter’s design balances an overall simplicity with a complexity of detail that fits, without disruption, into its total environment. The actual experience of the window (as distinct from photographs emphasizing Richter’s individual work) is the effect of light passing through it on the entire cathedral space. The window is a model of a life of faith that, rather than calling attention to its own faithfulness, is a medium by which the light of Christ bathes and transforms everything and everyone in its sphere. As faith depends on Christ, the window depends on light for its life. Light makes the window three-dimensional; without light, it is only a flat design waiting to be realized. Without Christ, faith is a two-dimensional cutout waiting to be brought to life.

Writing in the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, Friedhelm Mennekes compared Richter’s work to an icon as a “window of eternity.” We are not meant to look at this window, or even through this window, but rather see by this window’s transfiguration of reality. The entering light is also variable; some may even say that it functions by chance. As the sun crosses the sky, as clouds pass and the weather changes, from moment to moment, the light changes.

One of the best interpretations of this window was offered by cathedral prelate Josef Sauerborn. At the installation service, Sauerborn delivered a sermon on the theme “light is more than only light,” in which he described how Richter’s window reveals a hidden nature of light. Describing the cathedral as an “architecture of light,” Sauerborn used examples from Genesis and the Psalms of light as evidence of God’s past, present, and eternal creative activity. Sauerborn ended by connecting the light within the cathedral to the incarnation of Christ.

Shortly after the window was dedicated, it became embroiled in controversy, however. Joachim Cardinal Meisner, Archbishop of Cologne, who had attempted to prevent Richter’s design from being implemented, was not present at the installation ceremony, but was quoted in a local newspaper as saying that the window “belongs equally in a mosque or synagogue.” He added, “If we are going to have a new window, it should clearly reflect our [Christian] beliefs, not just any beliefs.” Richter responded that, personally, he would not have been able to make a work for a mosque and that this window, specifically designed for Cologne Cathedral, could not fit into any other cathedral, much less any other sort of religious institution.

The cardinal’s denunciation of Richter’s design stemmed from his preference for a pictorial subject, such as a nativity scene or a saint. However, his criticism misses the function of the stained-glass window in the Gothic cathedral, where its raison d’être is to fill a sacred space with a particular and, if the window is any good, unique sort of transformed light. The light filling the space in distinct bands of color is the fulfillment of the window’s specific design and purpose. Too often stained-glass windows are viewed as painting by other means. But the theological foundation for the development of these windows as an essential element of the Gothic cathedral was incarnational, not pictorial. In the twelfth century, Abbot Suger, whose designs for Cathedral of Saint-Denis are considered the genesis of Gothic theological aesthetics, described stained-glass windows in stark contrast to the banal and either didactic or decorative windows that disgrace so many modern sanctuaries and, it seems, would have suited Cologne’s archbishop. Suger interpreted the light as a medium of incarnation by which God’s presence literally filled and transformed the space. The color of the window was to participate in and further make visible this presence. Of Saint-Denis, Suger wrote, “the work that shines in splendor, may it light up the spirit...may it enlighten men’s minds and may its true lights lead them to the true light of which Christ is the true gateway.”

The patron saint of Saint-Denis is Dionysius the Areopagite. In The Age of the Cathedrals, medieval historian Georges Duby condensed Dionysius’ influence on Suger to the formula “God is light.” Duby added, “Every creature receives and transmits the divine illumination according to its capacity.” Is not the exploration of each work of art’s capacity as a medium of illumination one of Gerhard Richter’s most central concerns, most especially in his window for Cologne Cathedral? It seems he understood the particular role of the window within the Gothic conception of the cathedral as a prophetic vision of the heavenly Jerusalem described in the Book of Revelation. Richter’s window is a significant achievement and addition, not only to Cologne Cathedral, but to the history of Christianity and the visual arts.

Cardinal Meisner was not the only person displeased with the new window. Benjamin Buchloh, art historian and Richter’s long-time personal friend, derogatively called the window “church decorations,” suggesting that its religious context robbed it of any of the critical qualities that would make it art. Buchloh has written extensively on Richter’s work and has significantly shaped its reception. Buchloh’s neo-Marxist agenda attempts to pigeonhole Richter ideologically by contending that the artist is painting to prove that painting is dead. Interviews between the two are almost comical, as Buchloh presses Richter to admit that he is strategically pursuing failure, and Richter counters that failure is not an option.

Buchloh paid the Cologne window an unintentional compliment when he wrote in Artforum, “The task of separating the Catholic Church...as the patron of Richter’s new magnum opus from the work itself, and thereby detaching the reading of its aesthetic achievement from the location where it is now housed, thus confronts us with admittedly considerable, if not insurmountable, difficulties.” Buchloh further revealed the prejudices that impeded his ability to engage Richter’s work in its sacred context when he asked, “Does the fact that the work was ‘blessed’ during the initial ceremony, in a primitive ritual with clouds of frankincense billowing through the church’s nave...have an effect on the meaning of the work?” That Buchloh found the window incomprehensible is less surprising than the fact that Artforum named it one of the best works of 2007.

The principal challenger of Buchloh’s pre-determinist description of Richter’s work has been Robert Storr, former curator at the Museum of Modern Art, who organized a 2002 retrospective of Richter’s art. In the exhibition’s catalogue, Storr wrote, “The existential misgivings about the medium Richter harbors as a practitioner are fundamentally different from the rhetorical certainties his postmodernist supporters have ascribed to him in their desire to make him a standard-bearer for their overdetermined brand of endgame speculation.” Instead, Storr attempts to place Richter historically in relationship to modernism by contending that Richter perpetually situates his own art between faith and doubt without intending to resolve these paradoxes. Storr sees the “dilemma” of Richter’s work in terms of dialectical binaries: “faith versus skepticism; hope versus pessimism; engagement versus neutrality; self-determination versus fatalism; imaginative freedom versus ideology.”

Though he is not as ideologically slanted as Buchloh, Storr’s reading of Richter has a Protestant accent that emphasizes the “perpetual,” and possibly irresolvable, fissure between the material and spiritual. (For those familiar with H. Richard Niebuhr’s categories, Storr would seem to adhere to the “Christ and culture in paradox.”) Storr writes, “engaged in a balancing act, Richter establishes a system [of blurring his paintings] for maintaining his and the viewer’s distance from the [painting’s] subject.” He also argued, “The viewer is thus left in a state of perpetual limbo bracketed by exigent pleasures and an understated but unshakable nihilism.”

These statements do not match my experience of Richter’s paintings. In works like Sea, Skull with Candle, Cathedral Corner, and Reader, I have found that Richter restores my access to a sacramental mystery which is present in every moment, but to which I am too often indifferent. Richter’s pregnant uncertainty encourages my trust by opening previously unseen possibilities of belief.

A description of Gerhard Richter’s artistic strategy as one of expectant skepticism fundamentally differs from the dominant characterizations of his work by Buchloh and Storr in that it attempts to connect central themes of Richter’s art with a sacramental, even alchemical, conception of artistic practice that is particularly strong in Germanic art. Starting from its theological and aesthetic foundation in the Gothic cathedral, particularly in the region of Cologne, this tradition has included the work of such notable artists as Master Bertram, the Master of Saint Veronica, Martin Schongauer, Tilman Riemenschneider, Matthias Grünewald, Albrecht Dürer, Albrecht Altdorfer, Hans Baldung Grien, Caspar David Friedrich, Philipp Otto Runge, Otto Piene, Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, and Sigmar Polke. In my opinion, that Gerhard Richter arrives at the sacred via a path of skepticism enhances rather than discounts his participation in and unique contribution to an art that seeks divine grace waiting to be revealed in the mundane. With his Cologne Cathedral window, Richter returns this tradition full circle, to its religious center.

Although he was raised in the Protestant church, Richter’s sympathies are Roman Catholic. I would propose that a more accurate reading of his project has more to do with a closeness to the sacred, or at least a longing for a closeness, than distance. In his book Analogical Imagination David Tracy argues that Catholic theology emphasizes God’s immanence to creation, while Protestantism emphasizes his transcendence over it. Yet, by its very nature, the “analogical imagination” sees an indirect path between earth and heaven. I am inclined to agree with Robert Storr’s statement, in a 2007 essay, “Of Which We Can Be Certain,” that “as always with Richter, a negative premise chosen in resistance to received ideas may become the key to developing previously unrecognized or unrealized potential in those very same ideas once they have been stripped of their aura of philosophical, historical, or formal necessity.” As a medium of expectant skepticism, Richter’s art attempts to find a form of faith that can withstand the scrutiny of modern experience.

Given that Richter’s name means “judge,” the critical discord that has met his work, particularly those works with sacred references, both in Christian and art world circles, seems strangely fitting. In fact, by openly voicing his own religious and artistic agnosticism, Richter invites us to be skeptical of his propositions, as long as we are, as he has been, open to the prospect of belief.

Although he makes no profession of personal faith, Gerhard Richter’s window for Cologne Cathedral has done more to make a case for the relevance of Christianity to the visual arts of the twenty-first century than any other single work made in this decade. Even Benjamin Buchloh concluded his essay by asking if “these turns to tradition are just personal aberrations, opportunistic deliveries, or whether these...constitute in fact an actual desire for a return to the folds of the spiritual, the religious, and the transcendental...with more urgency than at any other time during the past fifty years of art production.” I would suggest that, in fact, a reemergence of a contemporary religious art unlike any we’ve seen in most of the past century is now taking place.

But it is not as simple as that. Richter’s window for Cologne Cathedral asks: What would a work of art be that is at once contemporary and Christian? If one purpose of art is to provoke us to consider important questions about the human experience as we encounter it today in new ways, Richter’s window is a great contemporary work. If one purpose of art in the church is to draw us to see the presence of God in our midst in a tangible way that draws us to worship him, all of which depends on both our capacity for faith in God and capacity for looking at art, Richter’s window encourages both. With his work at Cologne, Gerhard Richter has restored more than a window. His work restores the possibility of an art that is at once authentically religious and authentically contemporary. It restores our capacity to believe.