Sobia Ahmad is an interdisciplinary artist from the DC area. Her background as a community health worker informs her interest in social practice and community-engaged art. www.sobiaahmad.com

Image: Can you talk a bit about your background and how you grew up?

Sobia Ahmad: I was born and raised in Pakistan in a multigenerational household. I come from a lineage of farmers on both sides, and our shared ways of being were and are rooted in that modest way of living. My childhood was filled with large family gatherings and shared meals. Eid celebration days especially were about food, punctuated with five collective prayers. We’d lay out blankets and prayer rugs in the courtyard, and all the aunts, uncles, grandmas, and cousins would stand shoulder to shoulder to perform salat, the Islamic prayer. I really value that prayer, both in the house and at the mosque, was a huge part of my childhood. I moved to the US when I was fourteen and went straight to high school. It was quite a transition!

Image: How have ideas of diaspora and home surfaced in your work?

SA: I’m interested in how immigrant, uprooted, and exiled communities create sanctuaries through spiritual practices, ancestral rituals, and inherited memories. In my practice, I explore the notion of home from various angles—physical, geographical, spiritual—to break open what a home is and can be.

In my recent work, I’ve explored how sociopolitical power structures affect our understanding of home. But I am not interested in limiting ways of belonging, and home to me is not a country or a nationality. It’s both bigger and smaller than that. I do have an attachment to the courtyard of my childhood home. It resurfaces in my dream-memory a lot, and I think of it as a container for ancestral knowledge.

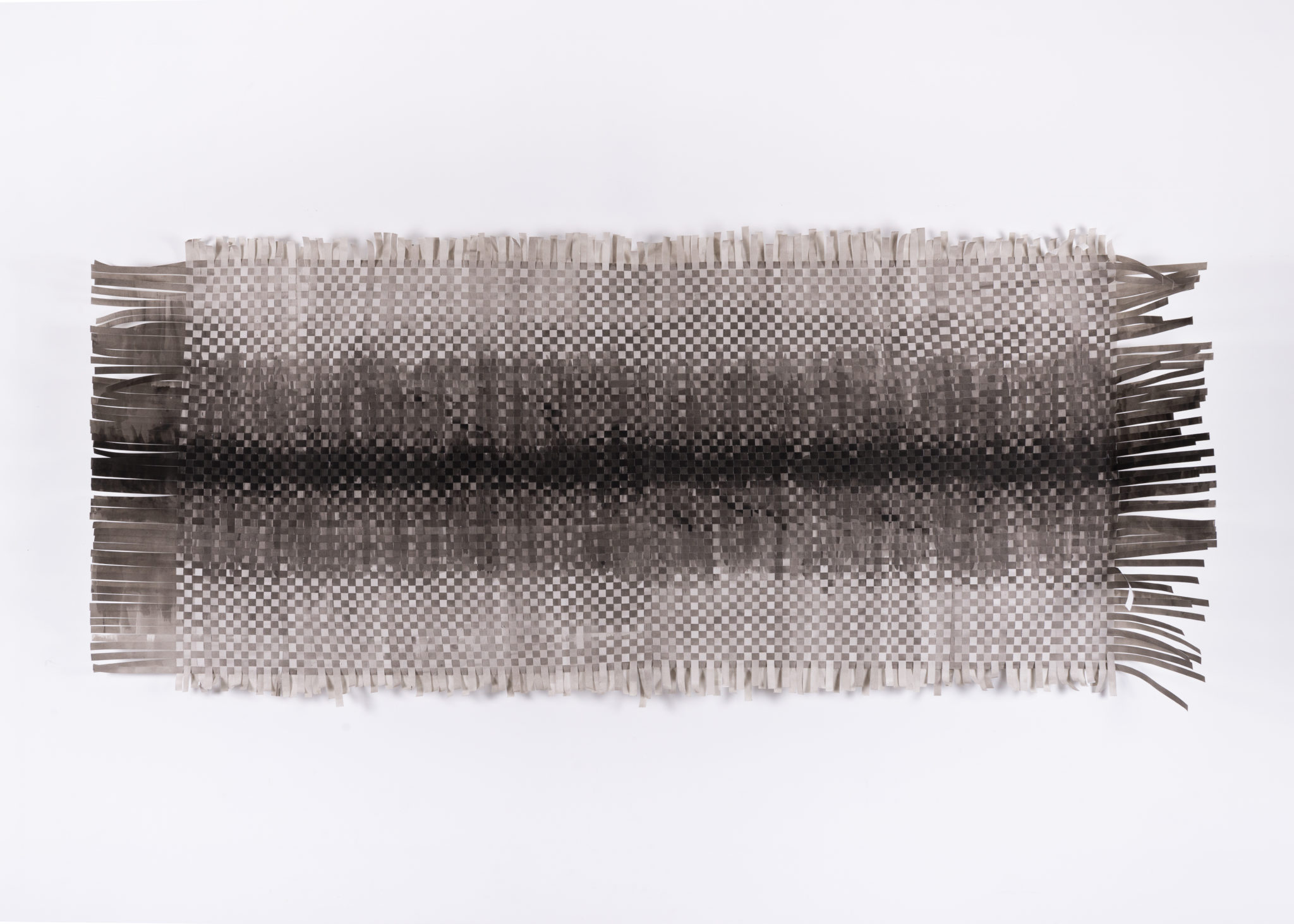

Sobia Ahmad. Landmark II (detail), 2018. Handwoven dyed paper. 36 x 72 inches. Photo courtesy of Catalyst Contemporary Gallery, Baltimore.

Image: Recently, you’ve been learning a lot of new skills connected to your family and heritage. Can you talk about that process and what it’s unlocking for you?

SA: I’ve become interested in various craft and weaving techniques and am attempting to re-create everyday objects that were part of my childhood. I’m currently working on a traditional woven bed of the kind that served multiple purposes in the courtyard of my home—a daybed, a surface to clean rice or dry chilis on, a gathering place.

I’m crowdsourcing these skills from local weavers and the older women in my family who are now scattered all over the world. They’re sharing stories of various such beds they’d woven or inherited and sending videos and patterns over WhatsApp, all of which I’m loosely organizing into a knowledge bank of sorts. It feels like I’m gathering pieces of a puzzle from different loved ones. It’s a multigenerational effort that is shifting my studio practice in magical ways.

The craft and materiality of weaving is not only helping me to reconnect with family history but also bringing me back into my own body. I didn’t know I was yearning to work with my hands so much. It’s a very slow process, and I’m really enjoying being a beginner. I’m thinking of it as an exercise in both “wrest” and rest. I am not only learning to slow down, but I’m also unlearning a lot, especially my constant participation in the productivity culture that I had internalized so much.

Sobia Ahmad. wherever you are is called Here, 2019. Weaving and screen-print on rice bags. 14 x 32 inches each. Photo: Adam Bencomo.

Image: When you and I have spoken, the word “Here” comes up a lot. What kind of temporal and spatial experience do you want viewers to have when they see your work?

SA: The idea of “Here” became very present for me during the early months of the pandemic while I was living near Rock Creek Park in DC. During quarantine, I spent a lot of time among the trees. That daily solitary ritual of walking in the woods pushed me into a contemplative space that helped me navigate my own and our shared grief and joys in a grounding way.

“Here” can be anything: Here is the pandemic; Here is the long overdue reckoning with white supremacy; Here can also be a momentary state of mind, an intimate inner struggle, or a physical location. What happens when our personal and collective Heres intersect, intertwine, and collide? Our Heres are ever shifting and may be marked by unease, yet being present to our Heres can show us myriad possibilities.

I’ve invited many people into this idea via workshops that reflect on the idea of Here through personal ritual, weaving, conversation, and silence. I send them some questions that invite them to enter their own Heres, and I ask them to bring materials to weave that inform their idiosyncratic narratives. The process and shared space are the crux of the work.

Sobia Ahmad at her studio at Halcyon Arts Lab, Washington DC. Photo: Chris Ferenzi.

Image: Do you have particular ritual practices—religious or not—you find yourself returning to in the studio?

SA: I regularly listen to Qawwali in the studio. It helps me enter my flow state. Qawwali is the devotional music of Sufis from Pakistan and India. It’s mystical poetry by Sufi saints written hundred of years ago and sung by ensembles of folk singers from the region.

I also listen to the podcast On Being in the studio. My favorite part is Krista Tippett’s opening question to each guest: “Was there a religious or spiritual background to your childhood? How does it inform who you are now?” I love the multiplicity of ways people enter that question.

Also, I recently put a prayer rug in the studio that’s doubling as my nap corner. In early 2021, I committed to regular naps in the studio. It’s a new practice for me that I hope to continue.