AS A FIFTH-GENERATION MORMON, I grew up hearing stories of my pioneer ancestors who left behind all they had to build a new Zion in the wilderness of the American West. My maternal great-great-grandparents sailed from Liverpool, England, in 1853 to New Orleans and took a riverboat up the Mississippi to Iowa, where they gathered supplies for the overland journey. Like the other new immigrants in their wagon company, they saw themselves as the latter-day house of Israel, following their own Moses, Brigham Young, to the promised land, fervently believing that God required this sacrifice to build a strong people devoted to the faith.

For weeks, they made their way across the plains in an ox-drawn wagon before dropping down into the Great Salt Lake Valley, which was nothing but a barren desert. I try to imagine their shock at trading the verdant landscape of England for a formidable desert ringed by the rugged Wasatch Mountains on the east and a dead, salty lake to the west.

Given such a heritage of self-sacrifice, it’s perhaps understandable how members could commit their entire lives to the Mormon faith, with its strict dietary laws and modesty codes. For many, adherence to these outward manifestations of obedience demonstrated commitment to the tribe and telegraphed their righteousness. I was taught to revere the founder of the faith as a virtuous, nearly perfect man, hand-picked by God himself. The only thing I found unsettling was the church’s former practice of polygamy, which formally ended with the 1890 Manifesto. I was assured that it was for the building up of the kingdom, to raise a righteous seed, and that God’s ways were not our ways. Like any aspect of our history or practice that gave me consternation, I placed it on my metaphorical shelf to deal with later.

Then everything changed. In the early 2000s, an enormous trove of historical documents, letters, and journals from Mormon history flooded the internet. (Paradoxically, though protective of their secrets, Mormons have always been tremendous record keepers, filing away every scrap of writing and every syllable uttered by past leaders.) The church could no longer hide away the unsavory moments in its history. As I voraciously read everything that I could get my hands on, I realized that the tidy narrative I had been raised with was a glossy fabrication. The real history was raw, messy, filled with debauchery and sexual intrigue. My shelf was shattered, my faith in ruins, and I was physically, emotionally, and spiritually exhausted. What do I do now? Should I walk away like so many others?

During this tumultuous time, I happened upon James Fowler’s theory of the stages of faith development, and it resonated deeply with me. Fowler likened a person’s faith progression to a child’s relationship with his parents. The very young child reveres his parents as near-perfect beings, imbuing them with a godlike status. As this child matures into adolescence, he begins to discern that his parents are far from perfect, a disappointing realization that often leads to anger and rebellion. Eventually the child reaches adulthood and begins to form a new a relationship, one that acknowledges his parents’ weaknesses while recognizing and sometimes celebrating their strengths. I began to see my own path through this new lens, no longer fearful of the destination.

Like the young adult, I began to pull away from my fury and frustration to make room for a more nuanced paradigm. I was confronted with the reality that a perfect church could not exist, that the leaders that I had grown up revering were flawed and very human. I no longer felt pressure to outwardly conform to the institution. Instead, I turned inward and rekindled a deeper, more personal spirituality. I sifted through the ruins of my tradition, found the pieces that resonated with me, and discarded what didn’t. At last, I could shed the debilitating millstone of polygamy. As I rebuilt, I began to experience deeper connections with the divine and a true sense of transcendence. I abandoned the black-and-white thinking of my early years and learned to navigate along the borderland, interacting with true believers and disillusioned members alike. The Mormon church is no longer the arbiter between me and heaven. Instead, it is a vehicle that helps me toward my destination, oneness with God.

My Paradigm Shift series springs from the devastating sense of loss I felt when my belief in the sanitized history of the Mormon church imploded. The overarching narrative of the paintings traces the arc of my journey from cataclysmic destruction and terrible sadness to the reclamation of my inner peace and eventual reconnection with my Mormon tribe. I see myself in conversation with some of the brethren from the middle of the twentieth century who were responsible for constructing what Mormons call the “faithful narrative.”

Doubt, 2018. Oil on canvas. 40 x 40 inches.

The drumbeat was constant: Don’t read anti-Mormon literature. It is evil and will destroy your faith. Stay safely tucked inside the windowless house. Don’t even think about lifting the blinds to see what might be outside. But what if this house is not exactly what they are telling me? There is light coming in through a crack in the wall. With that tiny bit of light, I can see that something’s broken.

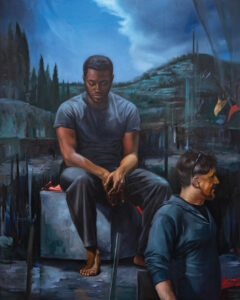

Outside the Walls, 2023. Oil on canvas. 60 x 48 inches.

Like the prisoners who leave Plato’s cave, I opened the door and stepped outside. In the full light of day, I saw that what they were telling me was wrong. So-called anti-Mormon literatureis our real history, raw and unvarnished. The incessant drumbeat has stopped now; too many people know. But the true believers who tenaciously guard the house still find us dangerous. Those of us who know are outside the walls. The house is not a house but a fortress.

Lost Saints, 2022. Oil on canvas. 60 x 48 inches.

In Italy, I drift through churches and museums full of Catholic icons and reliquaries, pieces of saints embellished with golden filagree, tucked inside ornate caskets. So many parallels. We worship; we adore; we need our saints to be perfect. Why was it so hard to realize that they are just like us?

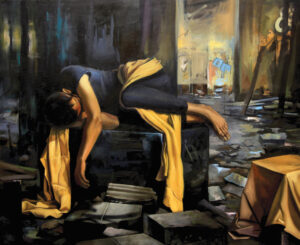

Free Fall, 2022. Oil on canvas. 72 x 60 inches.

A trapdoor opened beneath me, and I plunged down, down, down, not knowing how far I would fall. Mortality, eternity, death, resurrection, agency, hope, despair-all a blur rushing past me as I fell. Then my feet found solid ground in an unexpected place. Like a crusader back from the Holy Land with a shipload of precious earth from Golgotha, I rebuilt my house on sacred ground. And like Eve, I embraced the fall forward, finding redemption in the healer’s wings. (The fresco behind the figures is from Buonamico Buffalmacco’s Triumph of Death in the Campo Santo in Pisa.)

Processional, 2023. Oil on canvas. 60 x 72 inches.

Don’t ask questions, just move along. Nothing to see here. You can’t pick and choose; this isn’t a cafeteria. Don’t get off the train; it’s picking up speed, and if you get off you can’t get back on. Just polish the machine and keep it in good working order. All the little parts must be humming along.

But where are we going? Are we tethered to a grinding wheel, treading the same circular path over and over, or are we traveling forward like pilgrims on their way to Rome?

Limbo, 2022. Oil on canvas. 48 x 60 inches.

I am past exhaustion, laid bare, my bones picked clean. My anger and my sorrow have hollowed me out and left me humbled. Like a child after a tantrum, I curl up, finally ready to listen to the quiet voice that says, Be still and know that I am God.

Constructing the Myth, 2022. Oil on canvas. 60 x 72 inches.

I see what they did. They polished and burnished until all the blemishes were hidden. They crafted a new golden legend and warned us not to look deeper. Truth is not always uplifting, they said. Truth destroys. But they forgot one of the deepest truths of all: “For there is nothing covered, that shall not be revealed; neither hid, that shall not be known.”

Transcendence, 2020. Oil on canvas. 60 x 48 inches.

I no longer drag the remains of the windowless house built on sand behind me. That heavy burden is gone. I left it at the feet of the master builder. My new house is full of light. Its windows and doors are open wide, for the unseen wind to enter in. I sing a song of the sublime, a beautiful aching, a longing for home.

East of Eden, 2023. Oil on canvas. 48 x 60 inches.

They told me that since I’m a woman, I had no voice, that it was not my call, that it was selfish to want more. Then why did God plant this hunger in my soul? Are they punishing me for Eve’s transgression? Why? Is it because there is a terrible beauty and strength in the divine feminine? After all, wasn’t it Eve who first understood that we must leave the garden and embrace mortality? As I travel my own circuitous path toward enlightenment, I find my voice and raise it heavenward. I cannot return to Eden. Instead, with my face upturned, I journey eastward toward God.

Digital images courtesy of Woodward Gallery, NYC. Margaret Morrison is represented by Woodward Gallery.

Margaret Morrison, a professor of art at the University of Georgia, and has been represented by Woodward Gallery since 1995. Her work has been featured in national and international museums and art institutions and published in prominent art publications.