What follows is a written conversation between painter Bruce Herman and patron Walter Hansen. The two just completed a three-year project that involved producing a cycle of images on the life of the Virgin Mary in two large altarpieces that have been exhibited in the United States and are now installed semi-permanently in Monastery San Paolo, a thirteenth-century Benedictine convent in Orvieto, Italy. (The convent houses Gordon College’s Studio for Art, Faith, and History, a conference center, artists’ retreat, and undergraduate study facility.) The new altarpieces reference a Renaissance style called “sacra conversazione,” traditionally depicting the Virgin and Child surrounded on each side by saints or other figures in “conversation” with the central image—a form that offers a metaphor of Christian community across time and space. This present-day conversation between artist and patron addresses their working relationship, including some of the issues surrounding the commissioning and making of contemporary religious art where there is active participation on the part of the patron.

Bruce Herman: It’s not every day that a contemporary painter has a chance to work with a group of people committed to a subject matter and setting that guarantees receptivity and celebration of a shared vision. So I’m lucky—and blessed—to have had an opportunity to do this cycle of paintings on the life of the Virgin Mary. The norm of the artist as free agent (often so free she doesn’t even have a job) is one I’ve never been really happy about. I value my artistic freedom like anyone else, but only within the limits that real communication imposes. You can’t have utter autonomy and expect anyone to really care about what you’re painting, much less fully get it. In grad school, back in 1977, when I started trying to take on the grand narrative of Christian religious art, everyone around me thought I had committed intellectual suicide. After all, they said, this stuff is at best moldy and anachronistic; at worst it’s mere illustration or propaganda. Back then I had no thought that thirty years later I’d be doing large altarpieces on the subject of Mary for installation in an Italian hill town. Nor did I ever think I’d have an exhibition of paintings of the saints in an Italian museum housed in a sixteenth-century palace.

Plate 1. Bruce Herman. Rome: A Vision, 2003. Oil on canvas. 56 x 46 inches. Collection of Walter and Darlene Hansen.

Walter Hansen: When I first visited Orvieto and attended the exhibition of your work at Palazzo dei Sette there, I looked at your painting Rome: A Vision, one of your series of saint paintings [see Plate 1]. What I saw was a man sitting in the foreground, his chest pressed against his knees, his head bent down to the ground, and his whole body heaving with heart-rending sobs. In the background I saw a city that looked like Rome, but the city was falling down, half-submerged in water. What I saw made me think of Christ weeping over the city, not only Jerusalem or Rome, but the city of humankind, sinking into self-destruction and despair. Then I noticed that Christ’s arms are reaching down and his hands are forming something from the dust of the ground. I felt a sense of hope: I saw this figure building a new city in the midst of the ruins of the old.

When I told you what I saw, you said you were grateful, even though you had something slightly different in mind. You didn’t correct my interpretation, but accepted it as a true and good reading. Your gracious way of including me in your process of understanding your work emboldens me to enjoy an ongoing conversation with you, one that’s let us both discover additional layers of meaning in your work.

In his book Grace and Necessity, Rowan Williams encourages us to search for the “excess” of meaning in art:

[T]he artist does not exhaust the significance of his or her labor, but creates an object, a schema of perceptible data, that will have about it the same excess as the phenomena that stimulated the production in the first place. Art moves from and into a depth in the perceptible world that is contained neither in routine perception nor in the artist’s conscious or unconscious purposes.

Your way of continually asking me what I see in your paintings invites me to find more than you have expressed in your own intentions.

BH: Your interpretation—your encounter with Rome—is not only valid, but to my way of thinking gets at the crux of what I am attempting to do. For me this is central: the sense of connecting, the feeling that the thing I’ve been carrying with me and laboring over in the privacy of the studio has come to life for someone else. We’ve talked about this before—the role of the interpreter, the critic—not just as a passive recipient, but as a participant in the art, almost a co-creator alongside the artist.

John Skillen talks about the four constituencies of art: artist, patron, interpreter, and “community of use” (those for whom the work is meant—which might include those not yet born). When you stood in the museum in Orvieto and encountered that painting, you were standing in the role of Skillen’s “community of use”—you were the one for whom that image was meant.

Martin Buber speaks of this eloquently in I & Thou:

The eternal origin of a work of art is that a human being confronts a form that wants to become a work through him…. Such work is creation, inventing is finding…. As I actualize, I uncover. I lead the form across—into the world of [things]. The created work can be experienced and described as an aggregate of qualities [as a thing among things]. But the receptive beholder may be bodily confronted now and again.

Buber’s idea that the responsive beholder actually brings the work to life again, liberating the form, has appealed to me since I first read it more than thirty years ago. And Rome: A Vision was definitely one of those images that just came to me. Sometimes I labor endlessly on a piece only to lose it completely and have it crash and burn. That one just seemed to appear and paint itself, and your receptivity brought it to life again in the museum. What I had in mind was complemented and completed by your responsive interpretation.

WH: Since you made me feel so at home in your creative space, I was happy to participate in funding this major cycle of paintings on the Virgin Mary and to be further involved in their development by talking with you about your work as it progressed. Although I’ve enjoyed being a patron of artists by purchasing paintings, I had never before become a patron in the sense of engaging directly in the creative process. So the opportunity to travel with you and learn from you was very appealing. Your conversational approach pushed me out of my area of academic expertise, biblical criticism. You repeatedly invited me to respond to your sketches, drawings, and half-finished paintings. I wasn’t able to give you much by way of guidance—and by the time I concocted some response, you were usually scraping away the images you showed me and going in a new direction.

However, an unexpected consequence of your requests for me to participate was that you catapulted me into a whole new level of involvement in the world of art. Since my wife is an artist, I have always enjoyed art and followed her around in galleries and museums—like a non-Christian following his Christian wife to church. But you launched me on a serious quest of my own. You have introduced me to artists and paintings I never understood or appreciated before. You helped me engage the work of old masters as well as modern and contemporary painters. We’ve talked at length about the likes of Caravaggio and Rembrandt, but also about modern artists like Picasso, Pollock, Rothko, and Philip Guston. Now I stay in the art museums as long as and even longer than my wife, not racing through, but drinking deeply from a few paintings.

Slowly, over these past few years with you, I’ve grown in my understanding of your process and I’ve come to share your vision, to see along with you what you are seeing. Even the areas of abstract expression in your paintings that in the past I would have quickly overlooked have become spaces of meditation and reflection for me.

By your inviting me into your process, we’ve both experienced the power of art to generate community. We’ve been drawn into the sacra conversazione. As we talk about your portrayals of the person and role of Mary, we experience a growing communion—with each other, with Mary, with Mary’s God, and with generations past and present who gather around her to worship her Son.

BH: Your patronage nourished this project significantly—and not just by meeting the financial need, as important as that was. Your wrestling with me as to how best to approach the subject was pivotal. I think John Skillen is right, that the work of art (that is, the work that art is meant to accomplish) is only fully realized when an entire community comes into being that supports and guides and enables the artist to do it. This is true even of a completely secular art community. What has been missing in contemporary religious painting is patronage. We’ve got lots of critics, and certainly some artists who are capable of tackling these subjects. But we have had few patrons willing to address the whole process and get involved.

As you know, the idea of addressing the Virgin Mary as a subject in my paintings began earlier than this particular project. About eight years ago, after a house and studio fire, and after another trip to Italy where I encountered religious murals and paintings of the saints, I began a series on the martyrs—Sebastian, Perpetua, Catherine of Alexandria, and others—to see if there was a way to make contemporary saint paintings. I had vivid memories of Boston art critics and museum people back in the 1980s telling me that this kind of subject matter could only be approached ironically, but I had a persistent feeling that they were wrong. I’ve sensed for many years that the tradition of biblical imagery in art is far from exhausted—maybe simply stalled out due to loss of nerve or imagination. To me, much of the recent religious imagery we’ve inherited is fairly shallow. I know this might sound odd, given more than a thousand years of tradition, but I honestly believe that new insights are arrived at in every generation. Why can’t a contemporary artist paint the Virgin Mary without irony—and maybe even specifically attack the problematic nature of much Marian imagery? Why can’t a century of experimentation in painting yield something relevant to that tradition?

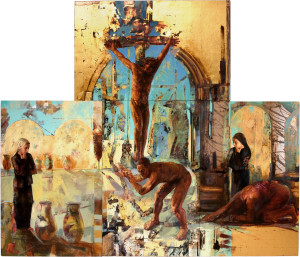

Plate 2. Bruce Herman. Annunciation, 2005. Oil and alkyd resin with silver leaf on wood. 76 x 96 inches, diptych. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. William R. Cross

Around the same time that I began the martyr paintings, I tried my hand at an annunciation image [see Plate 2]. It was largely allusive and indirect, with the entire left-panel being abstract—no visible announcing angel, but rather planes and areas of color and atmospheric texture that formed a kind of spiritual space or absence. Then, in November of 2003 I taught an experimental course at Gordon College’s undergraduate semester program in Orvieto, Italy. John Skillen, program director there, suggested I develop the Mary paintings for the convent where the program was housed. He was thinking the project would function the way some of the other bottega courses there had—as a pedagogical tool for exposing students to the atmosphere of a Renaissance workshop model, with teacher and pupils working on a common project. Several other faculty members in the program had tried this approach, and the results were what you’d expect: students learned a lot and projects were undertaken, but the actual art was more teaching tool than enduring work. I was not particularly interested in a classroom exercise that had didactic value but no lasting artistic merit, and Skillen had no real source for funding a more developed project. Nevertheless, I decided to begin in hopes that we’d come up with a plan.

I knew I might have at best one or two students capable of actually working on the images with me—and I had eighteen students to put to work over the course of a month. I explained to the class that I couldn’t really employ them all as artists, but that I had apprentice-like manual labor for them to accomplish: day after day of making traditional gesso from marble dust and hide-glue; day after day of sanding panels and re-coating, sometimes with as many as a dozen coats. I taught a couple of students the painstaking work of gilding with gold or silver leaf and set them to work once we had a few finished panels. Other students who had less interest in manual labor were given writing and research assignments. I had them study and report on the life of the Virgin Mary, drawing on resources assembled for them: the Bible, Jacopo de Voragine’s Golden Legend, art books on Giotto, Piero della Francesca, Orvieto’s own Luca Signorelli, and others. Some students scoured the little city for incidental details for the murals—drawing and photographing architectural fragments, studying Maitani’s stunning relief sculpture on the façade of the beautiful Orvieto cathedral, carefully sketching the fresco cycle behind the altar that is itself a life of the Virgin, and generally absorbing elements of the city and transposing them as notes for my work on the paintings.

By the time we had any panels ready for paint, I had only a week to work before the course came to an end for Christmas. I had to pack the panels up, wrap them in plastic to prevent mildew, and store them in hope that I could return to Italy at some point to work on them again. Nothing was certain, and the biggest obstacle was funding—for transportation, for time away from my teaching post at Gordon College, for materials, and for my labor.

As I said, Skillen really had no idea how to proceed, and no source of funding. Added to this uncertainty, the mother superior of the convent had seen the initial under-paintings and had reacted strongly against them because the figure of Mary was clearly based upon a young Orvieto woman (Elisa Lardani) who belonged to the charismatic Catholic group Comunità di Maria for whom she held an animus based on theological differences.

WH: I can well imagine why the mother superior would be upset. What amazes me about Mary in your paintings is how ordinary and yet how extraordinary she is. She looks like a down-to-earth, sensible young woman, not a fairy-tale, heavenly being. Nor is she a fashionable, striking beauty, a magazine cover-girl. Her beauty expresses a solid goodness; a stubborn purity shines through it. The extraordinary thing about her form is this unusual combination of beauty and purity [see front cover].

BH: That is precisely what I was attempting—not so much to drag Mary down to our level by using an Orvieto woman as a model, but to show that what is taken for ordinary is in fact extraordinary. The problem with pushing our heroes and heroines beyond our grasp is twofold—one, we overlook the obvious reality that heroic humans are like us, that we can do what they do if we choose aright; secondly, we overlook that Mary’s yes to God is what we, as disciples of Christ, are all in fact called to do. She is the model of what a disciple is and does. From a theological standpoint I remain a protestant evangelical—but I have begun to see the historic church as having maintained a dimension of the Kerygma (the heritage of Christian teaching) that can only be received in the form of stories and images—of the saints, of the Apostles, and perhaps supremely of Mary. Not that my motivation for this work was primarily to teach church doctrine. Rather, I was exploring whether religious imagery still has power in our time, despite the unimaginative and weak recent paintings we’ve all seen.

For me as an evangelical, to approach the subject matter of saints and Mary was tricky—especially given that I have many devout Roman Catholic friends who have a special devotion to her and to other patron saints. While I don’t share their devotional practices, I have the highest regard for Mary, and for the writings of Pope John Paul II, who was a devotee of the Blessed Virgin. His work on a theology of the body along with his Letter to Artists have had a lasting impact on my own sense of vocation.

However, I had honestly never given much thought to Mary beyond the usual Christmastime stories and crèche tableaux. The biblical texts which mention her are typically laconic and at first glance seem to offer little by way of imaginative stimulus, so it never occurred to me to do an entire cycle of paintings about her. What I discovered when I began to prepare to paint was that the verses in Matthew and Luke which mention Mary actually describe, in their terse fashion, an extraordinary person. They depict someone whose contemplative gifts are matched by a prophetic voice and by a tenacity and commitment unequalled in the biblical record.

If, for instance, you compare Mary’s character to Elijah’s or Moses’s, I think she comes up winning. Her quiet humility is backed by a confidence that says a simple yes to God’s initiative to enter her womb. The terror that most Old Testament prophets report at the appearing of an angel of the Lord is well attested. Mary simply says, “Be it done unto me as you have said.” It’s no accident that her symbol in traditional iconography is the burning bush, engulfed in flames but not consumed, ever virginal.

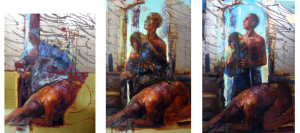

Plate 3. Bruce Herman. Miriam, Virgin Mother: Via Activa, 2008. Oil and alkyd resin with 23kt gold and silver leaf on wood. 95 x 154 inches, triptych. Collection of Gordon College in Orvieto, Italy.

While working on the paintings I was struck again and again by how young Mary was when she received her call, and yet how strong—and that as a woman she was the first disciple, the first witness, the first alter christus, carrying God into the world. The presence of clay jars everywhere in the painting cycle is intentional in this regard. My own understanding of Mary as a prototype of the church is predicated on this humble role of vessel. In the altarpiece Miriam, Virgin Mother [see Plate 3] the image reads sequentially from right to left like Hebrew texts, de-familiarizing in order to refresh the tradition. I chose her Hebrew name, Miriam, because I wanted to disentangle her from familiar devotional images which are often sentimental, even saccharine at times. Clay vessels appear in both side panels of the triptych, but in the center panel Mary is alone with God—she is the vessel, receiving the seed of God.

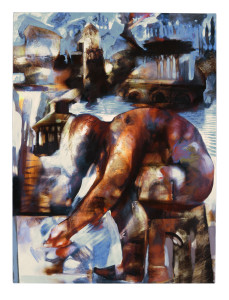

Plate 4. Bruce Herman. Second Adam: Via Contemplativa, 2008. Oil and alkyd resin with 23kt gold and silver leaf on wood. 125 x 144 inches.

In the other altarpiece, Second Adam [see Plate 4] the vessels reappear at Cana, as the water jugs in the left-hand panel. Here Mary is young, perhaps prior to the miracle of water-into-wine. She’s a contemplative, lost in thought before the jars in an enclosed garden (hortus conclusus—another traditional symbol of Mary’s virginity drawn from the Song of Songs). She appears in the right-hand panel as an old woman, as mater dolorosa, long after the miracle and its consequence, the death of her son on the cross. The costly miracle is the subject of her meditation and the source of her grief: the costly wine has become the blood of Christ, the cup of salvation—and the countless gallons that have been used in Eucharistic ceremony over the past two millennia.

WH: You mentioned just now the center panel of Miriam. This image throws me upside down as I try to align myself with Mary. Or maybe I should say that I am thrown right side up. In that golden, sacred space, Mary is perfectly aligned with God’s will—in the presence of God. I am the one who is not rightly aligned. My constant attempts to exalt myself, to exploit my prestige and my power, contradict the willingness of Mary to humble herself.

Mary’s upside-down humility embodies her song the Magnificat: “He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble.” This image of Mary stirs up an inner dialogue. Is this the beginning of the fall of all earthly empires raised up against God? Will I be turned upside down like this if I receive Mary’s son? Is this the humility required in order to be overshadowed by the power of God? Your image of Mary speaks to me more of loss and surrender than of empowerment and incarnation. Is that what you mean to communicate?

BH: That’s precisely what I’m trying to get at. The physical process of making the painting often begins in a kind of kenosis—loss and emptying. I have found over the years that simply sitting and composing constructively doesn’t work for me. The image seems to arrive stillborn, and the figures seem more like effigies than living presences. My paintings are the result of multiple layerings—layers of lost and found forms, figures, color, and texture that get scraped and abraded over and over again. That losing and finding of an image is actually part of the iconography of the work—and in some ways may be more significant than the final, visible image. Each of these paintings has literally dozens of figures and forms buried under the scraped and repainted surfaces. The vestiges of those forms resurface as newly visible fragments, constituting the final image. The thing represented is repeatedly submerged and lost in the history of its own making, reemerging in new places—like the figure of the true cross in Piero della Francesca’s famous mural in Arezzo.

In Second Adam, the left panel originally had, as you know, the figures of the patrons, you and Darlene. I was determined to include you two, since you were instrumental in helping this come to be, and after all in sacra conversazione altarpieces, the left panel is traditionally the patron panel. But you two got lost permanently when it finally came to me that what was needed was Mary, alone in an enclosed garden among the water jars, at the foot of the cross.

WH: I am relieved that our forms were buried. To stand at the foot of the cross was too high and prominent a position for us. You have given us that same experience of kenosis, of loss and emptying, by scraping us off and burying us beneath other vessels and forms. I feel much safer now that I’m hidden several levels below the surface.

BH: Yes, but I think the patron’s role is central—not to be hidden like the proverbial light under the bushel—but your presence is felt rather than seen. The lost image is still there as an absent presence, like the layers of scraped images, or the vestiges showing through a palimpsest.

Another example of this forming and de-forming, facing and de-facing, is the right-hand panel of Second Adam, where Mary is older, and shown with Eve at the foot of the cross. The iconography is pretty straightforward on one level—Mary is the “second Eve” whose record of obedience and humility replaces that of our great-grandmother Eve who rebelled. But the meaning gets more nuanced when you consider the history of this panel’s physical making. When I began, all I had was the rough figure of Eve and a vague series of marks and scraped passages of paint over the silver leaf. You can see in the succession of in-progress photos [see Plate 5] a process of losing and finding that included the figure of John next to Mary, the gradual erasure and re-conception of aspects of Mary’s figure, and the eventual complete elimination of John. The final result is the mater dolorosa alone in contemplation behind a larger-than-life suppliant Eve.

WH: At first I was very disappointed when John disappeared. But now I wonder if his disappearance fulfills his expressed desire to decrease so that Christ would increase. As John recedes into the background, the sorrowful mother draws us to contemplate the suffering of her son on the cross.

Iconography notwithstanding, your process of forming and de-forming deeply disturbs me. You construct a perfectly good Roman arch in gold leaf; then you shatter it by partially scraping it out and painting Christ on the cross, breaking it into pieces. As I have gone through this creative and destructive process with you, I have often wondered what will be lost by the next time I see your painting. But even though I’ve seen the loss of many good things because of your de-construction process, I keep coming back hoping to find something new.

Your way of losing and finding seems to reflect the flow of history—and of my own story. So much has been lost; so much has been found.

BH: Right. And the losing and finding is the whole point—both in the making process, and in the symbolism—which is why I’m always feeling that the meaning of the work is a fluid thing, not something I control and micromanage.

One last thing I’d like to discuss about our mutual enterprise is the uncertainty—the open-endedness and even potential futility of what we’re trying to do. Like the process of loss during the making of an image, I often feel that I am risking losing the whole thing—the individual painting, but also the whole undertaking of meaning-making. The fact is that we really can’t revive or recover the conditions of art-making that existed in the past, when artist and patron, interpreter and community all shared the same values and could count on a common story that bound them together. The reality is that we don’t live in a homogenous society with a shared vision of what matters, of what means what.

For better or worse, we live in a pluralistic setting where we stab at a means of communicating and connecting with others without any real confidence that we will succeed. And though this might result in a kind of incoherence, where everyone is pursuing their personal imagery, it might also become a fertile place for attempting again to connect, to give up some of our autonomy, to cross-pollinate and see something worth keeping grow out of our collaboration.

WH: We do meet each other again and again in the imagery you create. Even now as I sit at my desk and look up at your painting Rome: A Vision, I see a great city falling into ruins and feel with you the futility of so much of our making and unmaking. But I also see someone bending over to stir the dust of the ground into new life; I see you bending over your palette to mix your colors; I see myself bending over my writing to mix my words. We are connecting with each other in your forms and in your loss of forms. You have, in your paintings, created a place of communion, a place of welcome to non-artists like me.

BH: Regarding that welcome, in one of Saint Paul’s letters he states that in Christ there is neither Jew nor Gentile, no dividing wall of those who are in and those who are out. Christ offers no club, no special society of spiritual adepts or enlightened beings. Rather, he describes the perfect form of hospitality where the stranger is accepted as one of the tribe with all the benefits of an heir to the family fortune. It’s not so much about spiritual evolution as it is about welcoming others to a feast.

I’m looking for community that functions like a table set before enemies, and where those enemies can come and dine, just as Christ set a table for the enemies of God in the last supper. We were the enemies of God before his perfect hospitality brought us into communion. Art shouldn’t be the province of a special club—an in-crowd—but a place of fertile possibility for conversation, a feast where the best wine is offered last, and where everyone is invited, including the riff-raff—maybe because the original guest list had a lot of cancellations.

WH: Speaking of the best wine, I have a bottle of 2005 Bordeaux waiting for you here.

Detailed full-color reproductions of this entire project, along with essays by Rachel Hostetter Smith and John Skillen, are available in the book Magnificat. To order, send a check for $20 made out to “Gordon College,” memo line “Orvieto Mural Project,” to: Amber Primm, Barrington Manager, Gordon College, Wenham, MA 01930.