THE TERM “OLD MASTER” is a relatively new one, having originated in the English language around 1840 and become popular a few decades later. In American periodicals, its use became more frequent in the 1870s, right about the time a humbled, war-ravaged United States began looking abroad for fresh cultural inspiration. Today the term is most commonly used in the art market, to designate works by fine artists practicing before the rise of modernism in the nineteenth century. (In this context it has a kind of spurious glamour, as if to assure buyers they’re getting something priceless for a price.) But in the decades of its origin, “Old Master” meant something different; it meant canonical, accessible, timeless—even scriptural, perhaps. Old Masters were artists whose images (like the Bible’s words) were used to make sense of life and bear witness to the universality of human experience. Works by Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and Zurbarán were celebrated not primarily for their formal excellence or experimental audacity, but rather for the intense, street-corner familiarity of their ramshackle old men, their doubting Thomases and suffering saints.

This populist Old Masterdom can seem passé today, when the most ambitious artworks and the most elite art venues take their cue from academia (this is not surprising, given the importance of formal education in today’s art world); meanwhile academia, broadly speaking, has for several decades been in a stage of dialectical revolt against traditional views. Accepted narratives and aesthetic canons have been subjected to every kind of critical analysis. University humanities courses have become surveys of ideologies rather than recitations of accepted facts. In art schools, realistic representation has been stridently discouraged in favor of more experimental approaches. This has been highly beneficial, insofar as it has caused the guardians of tradition to specify, test, and enrich the grounds for their conclusions. But in the process, as far as general perception is concerned, the notion of an Old Master lineage has nearly lost its integrity. Thanks to new, sophisticated modes of investigation, we learn more about classic artworks every day, but we have lost sight of the common thread that once bound them together.

Of course the problem all hinges on the nature of “commonness.” It’s easy to imagine that the first Old Masterworks, so named during the Victorian period, were not really manifestations of universal myth, but commodities for lucrative trade or tools of cultural homogenization. Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that the term itself emerged just as America’s Robber Barons were forming valuable private art collections and consolidating political and commercial power. Perhaps the smoke-stained canvases of Old Europe, invoked as norms within a dynamic and modern present, did (and do) nothing but reinforce hierarchies based not on merit, but on a choking exclusivity. However despite all this, like mysterious guardians of some hermetic tradition, a few contemporary artists retain an Old Master outlook—and their tenacity is worth investigating. Outstanding among them is the Chinese-American painter Zhi Lin, whose Old Master methods are strikingly pure. Lin’s genuinely monumental canvases—tragic, solemn, and free of irony—rival the grandes machines of the old Parisian salons in their drama and gravity. His Five Capital Punishments in China evince a truly Solomonic fatalism, repeating a single, tragic subject across five different eras of Chinese history.

Confronted with Zhi Lin’s Five Capital Punishments, one tastes the dryness of Ecclesiastes. Classically proportioned figures in illusionistic settings eat, gawk, celebrate, weep, and kill. It is perhaps not surprising to find in Lin a sympathy with the artists of the distant past, for the China of the Cultural Revolution, in which Lin grew up, stamped out knowledge of the aggressively modern art (abstract, affective, experimental) becoming institutionalized in western art schools at about that same time. Consequently artists like Lin knew little of the theories of Clement Greenberg, who exhorted artists toward subjectless “purity of medium,” or of Allan Kaprow, who championed the fusion of art with our holistically sensed environment. When Lin left China in 1989 to study at London’s Slade School of Art, he briefly dabbled in abstraction—but only briefly. The expressive potential of the pure form or the passionate brushstroke, while considerable for the cultivated viewer, was not great enough to accommodate the stories Lin wanted to tell.

But perhaps the word “stories” isn’t quite right; what Lin creates are historically specific indictments, instantiations of universal conditions that, because of their narrative pointedness, cannot be waved away, wriggled out of, or lost within a protracted discourse on merely aesthetic qualities. In Robert Motherwell’s famous Elegies to the Spanish Republic, pulsing black fields like Rorschach blots conjure feelings of psychological turmoil and physical entrapment. A black ovoid form, viewed close up, expands into nothingness, denying the eye relief that might otherwise come from variety or contrast. Perhaps Motherwell’s canvases provide a spatial and optical experience somewhat analogous to mourning, resignation, or burial. Undoubtedly their spareness helped pinpoint, in the 1960s, the unencumbered sources of psychological effects that earlier figurative painters had taken for granted. But the vagueness of the Elegies somehow sidesteps the deliberateness, the violent willfulness, the hardness and sharpness of the human choices that caused the Spanish Republic to fall. In its majestic silence, Motherwell’s art somehow transcends the realm of physical struggle. And it is not the less powerful for that. But likewise, it does not point to solutions—that is, if the first step toward justice, in both action and knowledge, is the accountability that comes from recognizing specifically how the lineaments of tragedy are constantly being historically reenacted. One senses that for Motherwell it was enough to feel tragedy; but the Old Master asks “who,” “when,” and “why.”

I mention Motherwell’s Elegies because Zhi Lin cites Motherwell as an influence. And also because Lin’s five great, encyclopedic canvases—his only finished works since graduating from the Slade School in 1992—recall Motherwell’s Elegies in their cohesiveness and monumentality. Five Capital Punishments each represent, as the series title indicates, a different means of sanctioned human destruction occurring at a different juncture in Chinese history. The titles are Drawing and Quartering, Starvation, Firing Squad, Decapitation, and Flaying. In their size, their surface complexity, and their palette, Lin’s canvases do indeed provide a sophisticated aesthetic experience. But the colors and forms of his works also possess a moral specificity, a pointed narrative, supplementing the expanse of the canvas with a complex yet natural third dimension that comes from exploiting the potential not only of pure elements (form, color, space), but of particular signals that have become laden, over centuries, with meaning.

Of course the classical human figure, with its long pedigree, is a powerful and ancient symbol, once brought into a kind of rational stability by the artists of antiquity, who locked its facets together according to geometric laws. And then, throughout the history of western art, there are the many gestures of that figure—sweeping, groveling, declaiming—calling to mind not only lived experience and social ritual, but also those other, more purely aesthetic qualities illustrated in the work of abstract artists (senses of rupture, ascent, claustrophobia, truncation). Finally figure and narrative are deployed, in rhythms and structures, in a manner that honors time-hallowed narratives—tragedies and comedies with villains and martyrs, affirming patterns of human conduct as old as time.

But in the twenty-first century it has become possible to question the ethics of conventional meaning. The overwhelmed western eye can no longer tell the virtuous forms of lucidity from the evil pretenders, and measures have been taken to wipe out tradition-bound communication altogether. As early as 1916, the Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky suggested that the essence of true art lay not in its intricacy or incisiveness, but in its capacity to “defamiliarize” the objects we encounter. In 1960, the American critic Clement Greenberg equated clarity in artifice with the phenomenon of “kitsch”—that ignominious craft form of the overworked and undereducated, who wish not to be challenged but rather entertained. And in 1967, the French thinker Guy Debord indicted our “society of the spectacle,” wherein conventional signals have become stand-ins for genuine substance. For all of these critics, the image saturation of the modern environment has revealed the dangers of the eminently accessible visual sign. It is too easily manipulated, too violent in its effects, and too persuasive if repeated and multiplied.

Thus in our effort to locate and praise a beneficial conventionalism—that is, the conventionalism of the Old Masters—it becomes necessary to define the Scylla and Charybdis of “kitsch” and “propaganda.” Put briefly, the first appeals to the senses, while the other exploits social habits—and neither is worthy of being called fine art. The kitsch artist gives the public what it lusts after: imagine the Ziegfeld Follies, or contemporary pop music, or Victorian Coca-Cola ads. This is done through a gratuitous sensuality unencumbered by fear or paradox. Accordingly, the kitsch artist also blunts the sting of suffering. He nurtures the exciting jolt, the delicate rue, the fleeting generosity that his audience feels when beholding pain it will never experience, but he understands nothing of genuine sympathy. He is the bard of disheveled peasant girls who blush pleasurably at being ogled, and of wide-eyed children who simper with gratitude at being the object of a one-time charity event. The kitsch artist makes consumers feel satisfied with themselves.

The propagandist, meanwhile, far from gratifying her audience, uses powerful traditional forms on behalf of fleeting political ends. She shows how the myths and proverbs of folk or traditional culture are fulfilled by specific tyrants, religious leaders, or politicians. (Imagine the classical grandeur of the films of Leni Riefenstahl, admired aesthetically today despite the ignominious ends to which they were put.) Kitsch, then, is at base an engine of commerce; propaganda is spiritual falsehood. Both are corruptions of the image in a culture that has become too wise to the means of sensory manipulation.

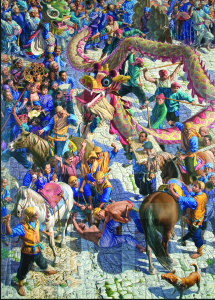

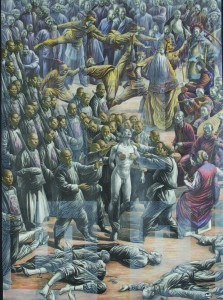

Plate 8. Zhi Lin. Five Capital Punishments in China: Drawing and Quartering, 2007. Mixed-media painting and screen print on canvas. 106 x 74 inches. Courtesy of the Frye Art Museum and Howard House Contemporary Art.

Lin, however, is neither a kitsch seducer, nor an ideological opportunist. His imagery is neither sensuous (despite its welcoming clarity), nor politically specific; on the contrary, no prominent figures are identified, and in Drawing and Quartering Lin depicts himself as silently complicit (He stands in the crowd watching, holding a fan [see Plate 8]. This is an established Old Master trope, occurring most notably in the works of Caravaggio.) Instead Lin follows folk and traditional artists in taking an ancient visual alphabet—a respectable, tried and true one, purged of fashion and worn by use—and using it to depict general, perennial conditions. In the Five Capital Punishments, spanning five periods of Chinese history, these include the destruction of the weak by the strong, as common thousands of years ago as it is today. It is by this means, Lin knows, that the Old Master shows how the new and the old are the same, how people are always greedy and afraid, how some people fall in love, how power is a fearsome thing, and how there is nothing new under the sun.

And finally we come to the abstract foundation of Old Masterdom—a foundation the average art consumer today cannot appreciate, resting as it does on philosophical assumptions few of us now share. For on closer inspection Lin’s work, far from eschewing artistic elevation, actually uses the image in a way that was once the particular inheritance of the great western visual tradition. Its obscurity today is the result both of modern commercial culture and of Enlightenment modes of knowing; yet it will reassert itself as the discoveries of poststructuralism continue to impact the art world.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in France, and later in much of the rest of the western world, the elements of visual narrative became oppressively fixed and formulized. The origin of this problem lay in the Enlightenment: when René Descartes pronounced “I think therefore I am,” he elevated the concept—the artificial sign—above the inarticulable substance of the living, breathing thing. Living objects became identified with their most useful or diagnostic characteristics—that is, with their presumed social value; they were no longer regarded as mysterious things-in-themselves. This was true especially in the realm of art, where norms of beauty, codes of emotional expression, and elaborate symbologies of privilege were imposed and exploited as never before. One need only look at the extravagant and ritualized court of Louis XIV to see how sign systems, and not genuine attributes, came to organize all life, down to the shaping of the human body itself. Consider the binding fashions popularized during Louis’ reign: the tights and breeches, the extravagantly artificial wigs, the impossible corsets. Meanwhile the land around Louis’ famous Versailles, far from serving its natural purpose, was re-sculpted to reflect a new “rational” dominance: hills were leveled, swamps were drained, and foliage was trimmed into pristine mathematical shapes.

Later, after decades of monarchical abuse, the visual codes of the Ancien Régime came into question. However, the power of the visual sign itself remained ascendant, though its custodianship shifted hands (from the Bourbon kings, to the body of revolutionaries, and finally to the vast class of the bourgeoisie). It is not surprising that, by the late nineteenth century, the fashioners of visual symbols—that is, artists themselves—began to claim an almost oracular power. If the concept or the mental image was the ground of all meaning, then it followed that the creators of images must be informed by a certain arcane insight or divine power.

Thus, beginning roughly in the 1860s, fine art could be understood as the fruit of mystical or transcendent perception. The symbolic confidence of the Enlightenment formulizers was sublimated by Romantic “prophets” into something not rational, but more freely spiritual; the artwork became a divination for a broader populace unable to “see” for itself. This artistic arrogance was no doubt exacerbated by the new culture of advertising, which immersed the broader populace in a shallow and deceitful visual vocabulary from which it could hardly extricate itself. Non-artists, themselves lacking the technical savvy to deconstruct the instruments of their sensory oppression, could seem less sensitive, less perceptive, less “spiritual” than the undeceived artists in their midst. Today, a materialist reluctance to invoke spiritual privilege has caused some artists to claim, not greater spirituality, but superior affective sensitivity. However as far as artist and public are concerned, the effects are the same. The forms of artistry remain “infallible” tokens of the artist’s separateness; meanwhile the public remains largely hostile toward this culture it financially sustains.

Zhi Lin’s intellectual development, however, occurred outside the reach of modern western thinking; consequently his own understanding of art and spirituality has not been pulled in the mystical or introspective direction followed by so many western artists disenchanted with Enlightenment rationalism, yet still enamored of Descartes’ Cogito ergo sum. For Lin, and for western artists before the Enlightenment (including the canonical Old Masters themselves) artistic form was, and is, the fruit of practical mastery of optical rules and the properties of materials. For these artists the saturated color or the sinuous line, rather than reflecting transcendent perception, make witty or poignant statements answering to the viewer’s and the artist’s shared acculturation. Consequently, viewer and artist become simultaneous witnesses to a shared truth—a truth communicated through the slippery, inadequate, yet evocative conventional signs that are the property of everyone, but which the artist alone has the patience and skill to manufacture. In the modern period, precociously postmodern works by Monet, Cezanne, and especially Picasso have methodically borne witness to the simultaneous conventionality and insufficiency of the shared means human beings use to communicate visually.

As we will see, for Zhi Lin, the delight and potential of art consists in just this slipperiness of the sign—in its provisional quality, arising from its origin in social convention, and not in private symbologies. Any other concept of art—anything more stable, more confident—reflects a kind of illegitimate ownership, truly a kind of infallibility, that puffs up the artistic product while at the same time speaking coercive words about what it purports to represent. (It is this quality that Marxist critics have railed against, and that various feminist and minority artists have challenged in their deconstructions of predominant types.) And it is not only the arrogance of Enlightenment-era introspection that thus “captures” the object. In an interview with this author, Lin cited Italian Renaissance perspective as a mechanism too redolent of cognitive conquest. In cases of both mysticism and rational ordering, there is an intangible seat of absolute perception, proposing the iconic frozenness of the sign and the spiritual or intellectual privilege of the artist. Lin believes in neither; thus he chooses an arguably banal, thoroughly unfashionable mode of visual knowing that is overtly and humbly common property. And he signifies his intent not only by foregoing elusive and esoteric content, but by trading the expected Renaissance perspective for the more splayed, strained, and topographically irregular visual field of the northern Renaissance artists, who strove heroically for clarity, but who never “perfected” their lens onto the living world. Accordingly, throughout the Five Capital Punishments, spaces are tilted so far forward that there is no horizon. They emulate, in a forceful and exaggerated fashion, Flemish “execution” pictures with high horizon lines, like the Saint John Altarpiece by Hans Memling (where the Baptist’s head is presented on a platter), and Dieric Bouts’s Martyrdom of Saint Hippolytus (where the Catholic saint is tied to four horses, about to be quartered like one of Lin’s anonymous victims).

What we see in Lin’s work, then, is an effort to manifest, by aptly chosen perceptible means, the fullness and commonness of shared experiences. Lin accordingly locates his identity as an artist not in any special intuition, but in a facility with craft, and with a certain happy capacity for matching form to content in a manner suitable to his audience. It is for this reason, likewise, that he continues the time-honored Old Master tradition of quotation and repetition, where quotation affirms the meaning of representation as repetition. For it is by repetition—that is, by pointing over and over again at the same thing, generation after generation, always using the same (inadequate) sign, that canonical communication takes place.

In Lin’s work, this repetition occurs on the narrative level by means of the egalitarian use of visual forms (i.e. classical figures) and perennial situations. But it also occurs on a thematic or programmatic level, by means of complex references that reproduce not only the basic morphemes of visual communication, but also whole “words” or “paragraphs” that have become canonical (proverbial, scriptural) by means of their success. Masters like Rubens, van Eyck, Ingres, Raphael, Michelangelo, Renoir, and Manet are known to have quoted entire figures or passages from the works of their predecessors. Meanwhile, poets have reiterated proverbs, and the refrains of the Dies Irae have recurred in the work of western composers from Brahms to Liszt to Sondheim to Berlioz. In this same way, Lin enriches his canvases with a sort of formal-historical erudition, where motifs from the history of art suggest both the complexity and the continuity of human life.

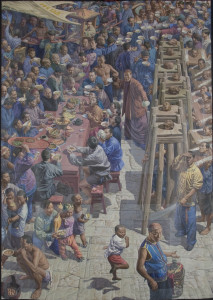

Plate 9. Zhi Lin. Five Capital Punishments in China: Starvation, 1999. Mixed-media painting and screen print on canvas. 106 x 74 inches. Courtesy of Howard House Contemporary Art.

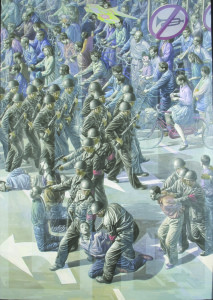

For example, in Drawing and Quartering (like all the Punishments it measures 12 by 7 feet and is mounted on a cloth scroll), a central figure dressed in rose lifts both arms in emulation of the major figure in Francisco Goya’s famous Third of May, 1808. This tactic is repeated in Starvation, wherein a long banqueting table recalls the plunging central apparatus of Tintoretto’s Last Supper [see Plate 9]. In Lin’s Firing Squad, a soldier in the foreground mimics a gravedigger from Caravaggio’s Burial of Saint Lucy [see Plate 10]. And in all of the canvases, Lin reveals his debt to the great visual poets of indifference—the most prominent among them being Pieter Bruegel, whose Landscape with the Fall of Icarus was famously glossed in a poem by W.H. Auden (“Musée des Beaux Arts”):

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters; how well, they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking

dully along.

Plate 10. Zhi Lin. Five Capital Punishments in China: Firing Squad, 1996. Mixed-media painting and screen print on canvas. 106 x 74 inches. Courtesy of Howard House Contemporary Art.

In each of Lin’s canvases, ordinary life proceeds alongside atrocity: peasants eat, watch acrobats, and enjoy civic festivals. And there is an added twist, for each of Lin’s quoted figures is an inversion of its prototype: the Goyaesque figure in Drawing and Quartering is not a victim, but an orchestrator, goading on the executioners. The table in Starvation is not secluded and sacred, but decked out in full view of miserable, bound prisoners. And in Firing Squad, the Caravaggesque soldier is an executioner—brutally effecting a victim’s death, rather than mourning it. In his inverted use of preexisting motifs, Lin himself cites the influence of paintings like Giovanni Bellini’s Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr, wherein the elegant saint is felled within yards of peasants chopping down trees. In Bellini’s canvas, the innocent woodsmen duplicate the posture of the saint’s assassin, just as Caravaggio’s gravedigger becomes a crouching gunman. Here, both Lin and Bellini seem to indict the common man for his blind complicity in the face of injustice. And by matching actions of earthly stewardship (chopping, digging) with actions of human oppression, each artist highlights the fundamental, ontological incongruence of man’s violence upon man.

And here lies the final, major implication of Lin’s approach: the ontological stability of the creation. Lin recognizes that art in the wake of the Enlightenment, in its claim to improve or spiritually capture its objects, compromises the intrinsic dignity of those same objects. In speaking oracles, this idealist art makes unassailable statements about the nature of reality—statements for which the ordinary viewer is not allowed to hold the prophetic artist accountable, and which may seem to upset common notions rooted in experiences of life, death, pain, love, and land. As long as the western viewing public remains in the chains of the Enlightenment, such an art will always be subject to iconoclastic impulses or to ham-fisted religious critique. When the Dutch Christian art historian Hans Rookmaaker reacted to modern art so shrilly in his (in)famous Modern Art and the Death of a Culture he did not see, in the work of Francis Bacon or Alberto Giacometti, improvised cries of pain that affirmed and utilized humankind’s shared visual language in the very act of distorting it. (There is a reason Bacon chose to quote Velasquez’s Pope, and why Giacometti quoted Greek kouroi in his attenuated walking men. Both artists knew that only repetition and convention can guarantee communication of a lived suffering that mere images, fundamentally, cannot capture.) Instead Rookmaaker saw a confident and demonic mysticism that proposed the ontological rewriting of humankind, and that spoke with a chillingly effective authority, thanks to assumptions about the artist’s transcendent mandate. No doubt Rookmaaker—who himself claimed insight into transcendent “structures” governing reality—believed in the myth of the artwork as oracle. And undoubtedly some artists have embraced and encouraged such views, believing their own dark visions to communicate essential spiritual truths.

Thus it is philosophical misunderstanding, not charlatanism or perversity, that has caused many westerners—and particularly religious westerners— either to distrust or abuse fine art. But a courageously retrograde oeuvre like Lin’s, with its comfortingly recognizable figures and its simultaneous use of the artistic image as a product of “mere” tradition, may serve as a corrective for poetic arrogance in an age that runs after signs and miracles at the expense of wisdom.

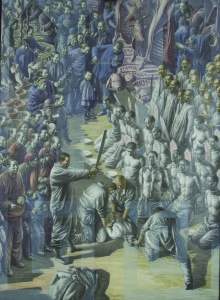

PLATE 12. Zhi Lin. Five Capital Punishments in China: Decapitation, 1995. Mixed-media painting and screen print on canvas. 104 x 74 inches. Courtesy of Howard House Contemporary Art.

And here is where Lin’s identity and cultivation as a Chinese painter is of special importance. For in the face of a recent western artistic tradition that has (in some quarters) forgotten both the humility of the artistic sign and the shared spiritual experience of all humanity, Lin asserts an outsider’s view of a universality that was always present. If the philosophical idealism of the (post)Enlightenment, together with the degradations of modern advertising culture, have estranged artist from public, it has taken the images of an artist from a different cultural milieu to show us the image we forgot: one of a roundly dignified humanity that can truly be united in myth.

Plate 11. Zhi Lin. Five Capital Punishments in China: Flaying, 1993. Mixed-media painting and screen print on canvas. 106 x 74 inches. Courtesy of Howard House Contemporary Art.

Thus in the Five Capital Punishments, Lin bears witness to humankind’s simultaneous self-vivisection and spiritual fraternity. This is literally figured by the physical integrity of the victims themselves, which Lin was careful to maintain, despite the ontological fragmentation implied by their means of death. A beheaded man is still a man, and so the foremost victim in Lin’s Decapitation leans delicately and pathetically beyond the lower bound of the canvas, his death-wound veiled [see Plate 12]. In Drawing and Quartering, the victim is shown before his disintegration, helpless as an infant on the cobblestones. And in Flaying, the seven prisoners awaiting punishment are shown clothed; the viewer is denied the expected vulnerability of exposed or bruised bodies. Indeed, even the central victim in Flaying is still “clothed” in his skin—there is no horror-movie stripping away of both identity and flesh [see Plate 11]. For a new Old Master like Lin, common language implies common essence and common knowledge. The meanings of art—though not its manufacture—are the province of everyone. The artist becomes accountable to his audience under the light of shared wisdom. And the spiritual unity of the human family is affirmed through witness to its yearning to cry out with a single voice.

Zhi Lin’s Five Capital Punishments cycle, meticulously researched and carefully prepared in numerous sketches, took the artist nearly fifteen years to complete, and was exhibited beginning in the spring of 2007. Lin is currently working on a series of watercolors that tell the story of Chinese labor on the transcontinental railroads. Titled Invisible and Unwelcomed People, the series will tour three American cities beginning in the spring of 2008. The new work reflects Lin’s commitment to two strategies: first, the use of eminently traditional visual signs, and second, the adoption of subject matter that reveals historical instances of social injustice. In their stylistic echoing of the works of British landscape painters like John Constable and Thomas Girtin, the watercolors in Invisible and Unwelcomed People continue to highlight the conventionality of visual languages, as well as the historical baggage such languages can sometimes carry. And in his choice of the still little-known theme of the immigrant Chinese railroad worker, Lin reinforces his message of equality grounded in our common humanity.