PAINTER SHAI AZOULAY recently moved into a new studio in Jerusalem, a city where he has lived and worked throughout his artistic career. His studio, however, is far from the domed sacred spaces and stony streets associated with the Holy City. I took a meandering bus to the western edge of town to visit his studio in Givat Shaul, a busy industrial neighborhood, and wandered through a complex of towering buildings before finding his second-floor studio. It is a bare, spacious room—a working space in a working building. Below it is a shop that makes vinyl signs. Stencil scraps litter the loading bays and machine parts punctuate the stairwell. The building pulsates with energy from the humming street below and the activity of people making things, each space its own colorful hive of tools, materials, and workers. “It’s kadosh (holy),” Azoulay exclaims about the setting as he welcomes me. For him, the studio is another holy site in the holiest of cities, albeit one brimming with playfulness and color.

Azoulay is a religious mystic, and he has the look of one: warm smile; kind eyes; full, graying beard; curious hat. But he isn’t distant from earthly demands. He’s the father of six children and maintains a rigorous studio practice, with an impressive roster of international exhibitions in the past year alone. In conversation, he’s focused, though his phone frequently vibrates (he’s also very active on Instagram). In his studio hangs a small, simple painting—his own—that depicts a religious Jew, dressed in black and white, giving a punk a piggyback ride. Azoulay relates the image to his own experience of growing up secular and becoming religious later in life: “My head is like two heads—I can be this and that.” Certainly his religious observance sets him apart in the decidedly secular Israeli art scene, of which he is a leading figure. This comfort in crossing lines and balancing contradictions defines much of his life and work, giving his paintings a likeable edginess. It also makes him peculiar. “I’m strange when I’m an artist; I’m strange when I’m religious,” he says.

This sense of displacement echoes within his family history. His parents both came to Israel as children, his mother from Spain and his father from Morocco, and he says his father felt frustrated with his inability to express his home culture. Shai was born in Kiryat Shmona, a verdant city in northern Israel not far from the Lebanon border. But when the prolonged Israeli-Lebanese conflict made the city a frequent target of bombing, his family relocated to Arad, a stark contrast to Kiryat Shmona. Located in the middle of the Negev Desert, Arad is surrounded by a bare, dry landscape. However displaced the family may have felt there, the desert had a profound influence on the young Azoulay, later reflected in a series of muted landscapes. The desert is “so active, but under the surface,” he says; it is “working from the quiet.”

Azoulay left Arad to complete the requisite three-year army service, then embarked on travels through Asia. It was in Thailand that he first felt the compulsion to make art. One day he began to paint a scene from a window, and as he worked, he felt “complete freedom.” He decided to become an artist, eventually attending Bezalel, Israel’s premier art school. After he completed graduate school (also at Bezalel), his career took off rapidly. Interestingly, at this juncture he also discovered God. He had been raised with some religious practice, but now he and his wife began exploring Jewish mystical texts in earnest, an exploration that eventually led to a religious awakening. He credits this experience with breathing fresh energy into his work: “When I discovered God, I found that painting was second. The work isn’t God. This gives you relief. It’s not so heavy. You can go on to the next painting.”

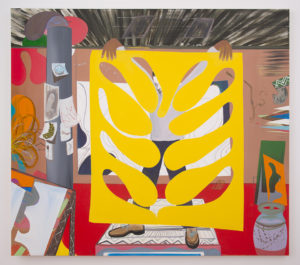

This generative, open attitude runs through all of his work. The paintings are energetic and loose, never laborious or precious. When I visited, he was working on a series of large paintings featuring the imagined scraps from Matisse’s cutout paintings. Azoulay has found that working on multiple paintings at the same time tempers the tendency to overwork or obsess about any particular piece. Although the cutout theme figures heavily in his recent work, he moves freely between many images: in one painting, a group of miniature figures encircles a tree under falling green rain; a yellowish painting depicts a tabletop still life crowded with real and fantastical objects; and in the largest painting on the wall, a cartoonish figure sits exhausted on the floor, legs splayed, yet still attempting some feat of painting with a brush extended upward. Is this last a portrait of the painter at work? This seems likely, as Azoulay himself is a specter haunting all his work. His paintings playfully probe his spiritual and artistic identities from all angles, and the exhausted artist is probably one.

But what about the cliché of the suffering artist? Well, not quite. “I won’t suffer,” says Azoulay when I ask him what rule he abides by in his work. “Artists can choose what they want to bring. I can bring joy and happiness.” Distancing himself from the somber tone of what he terms “post-Holocaust art,” he finds inspiration in the teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a Jewish mystic, teacher, and storyteller who died in 1810 in Ukraine. Nachman had a significant impact on the development of Hasidic Judaism, which stresses observance of Jewish law as well as spiritual fervency. Among his followers he popularized the practice of hitbodedut, or speaking with God in one’s own words, usually within the solitude of nature. Azoulay wakes up at four o’clock every morning to practice this tradition alongside Torah study and traditional prayers. In Hasidic practice, these disciplines are meant to enhance, not allay, the experience of joy. Nachman proclaimed:

Make every effort to maintain a happy, positive outlook at all times. It is a natural human tendency to become discouraged and depressed because of the hardships of life: everyone has their full share of suffering. That is why you must force yourself to be happy at all times. Use every possible way to bring yourself to joy, even by joking or acting a little crazy!

In Owl, Azoulay’s childlike joy is evident in the rambunctious yellow hue and whimsical shape of the dominant shape, which the figure holds up proudly for the viewer to see [see cover and Plate 1]. The rules are in flux here, adding to the childlike feeling—for what child doesn’t like to experiment with rules? Azoulay believes that in painting, “You can do everything that you want. The rule is no rules. You have to react to your own instinct, your own ability, your own attractions.” In Owl, Azoulay is clearly feeling that sense of freedom. Although the figure inhabits a cube-like studio space that adheres to systems of perspective and figurative rendering, there are small deviations from convention. A work table in the foreground flips upward in defiance of perspective. Though the feet of the figure are accurately angled and foreshortened, the hands flop down over the shape they hold, mystifying any attempt to understand them anatomically. An urn, also in the foreground, isn’t symmetrical, and the color throughout the painting, from the ghostly white of the figure’s face to the cherry red floor, is playfully unreal. Like a child, Azoulay jumps headlong in the painting, unafraid. But to emphasize only the work’s naïve quality would be overly simplistic, for here Azoulay also flaunts his adroit painting skills: the shapes are sharp and precise, the linear elements pulsate with life, the perfectly pitched colors articulate space, and the brushstrokes demonstrate a full lexicon of painterly mark-making.

This simultaneous embrace and rejection of “good” painting is what initially drew me to Azoulay’s work. His style reminded me of punk rock, which uses the form of music but demotes it in favor of urgency, attitude, and exuberance. As a Hasidic Jew, Azoulay is well acquainted with forms and rules. His is a religion where the law is holy and practice is governed by strict observances of diet, Sabbath, and dress, among other things. I asked Azoulay about his attitude toward religious laws, as he approaches rules so lightly in his art. “You have to imagine God,” he said. “You can’t be a believer with just rules. You will die. It’s robotic. The rules have imagination in them. They’re inviting you to imagine.”

It’s precisely this balance between structure and imaginative freedom that makes his paintings hold. Read religiously, they seem to propose that it is this balance that makes faith work: the commandments allow us to imagine God. Commandments are a structure that let us place ourselves within the knowledge of God’s holiness, grace, severity, and love. And, as in Owl, this experience can be a celebratory one, as we enter a place of faltering, of negotiation, but above all, a place of messy joy.

The most prominent element in Owl is the image of the yellow cutout, which dominates the canvas, front and center. If not for the negative space within, it would block out the scene of the artist in the studio. Its dominance is literal but also metaphorical. The character of the artist is overshadowed by it: it nearly eclipses his body. Yet he’s also in control: he’s holding it up and presenting it to the viewer.

The cutout itself is a fascinating and potent image. We can understand it and its reference to Matisse as the legacy (or scraps) of art history, with which the artist must contend. In addition, reflecting on Azoulay’s own geographical setting brings to mind the city of Jerusalem itself, a vast and complex historical reality that carries a long legacy of influences, both inspiring and burdensome. “You’re taking so many tricks from the masters but creating your own thing,” Azoulay says about the benefit of living in Jerusalem. For an artist and a spiritual person like him, the legacy of the past looms large. He’s generating imagery from the imagined leftovers of a Matisse project, but less overtly he also cites Picasso, Munch, and Vermeer as influences.

In addition to following the teachings of Rabbi Nachman, Azoulay locates himself within the tradition of Rabbinical Judaism, which believes that God gave Moses both written and oral law, with the oral law persisting as an ongoing dialogue of rabbis throughout the ages. In realms of both art and faith, he finds an openness, a sense of journey, where the past unfolds in surprising new directions. He describes Rabbi Nachman’s fairy tales as “stories inside stories” and “stories that are not finishing,” an observation that reflects Azoulay’s own receptive circularity.

In addition to interacting with the great rabbis and artists of the past, Azoulay engages with God as a creative force. This theme is particularly prominent in Creation Cycle [see Plate 3]. A dark cloud hovers over the scene, dropping rain upon a bonfire in the center of a chaotic space populated by: a woman roasting marshmallows, a stack of books, a ladder with a chicken perched atop it, various paintings and cups, and a fire hydrant, among other things. As Azoulay describes the painting to me, it’s very much about the creative process. There’s a tentative balance between creation and destruction here: “You have to burn something to get something,” he says of the fire in the center. It looks as if the fire is fueled by a stack of canvases, a reflection of the creative progress as arising from risk-taking and failure. Yet the fire hydrant and rain offer a sort of control. “There is a limit to this,” Azoulay explains.

Appropriately, the painting veers between chaos and control. The initial idea—a rain cloud and bonfire in a studio—is absurd. So much of the painting is unfinished: the cups and vessels are outlined as if provisional ideas, and the black vertical structure in the foreground (some sort of tree stump?) dissipates a quarter of the way into the painting. Yet the painting has structure holding it together in a seemingly magical way. Spatially, there are three horizontal bands—the gray cloud at top, a pink wall in the middle, and a brown floor at the bottom—and three vertical structures—the ladder, the fire, and a green rectangular shape. These elements create a grid around which the other elements cohere. Additionally, the sensitive modeling of the grays within the cloud and the precision of certain geometric shapes temper the crude execution of other elements.

Within Creation Cycle, the cloud, the fire, and the rain all recall elements controlled by God as signs of his power and creative force. As the Israelites wandered through the desert from Egypt to the promised land, a pillar of fire supernaturally lit their way by night and a hovering cloud led them by day. Additionally, fire and rain can represent the judgment or favor of God. Fire is an agent of destruction against Sodom and Gomorrah, yet a symbol of God’s holiness in the burning bush. Similarly, rain destroys the earth in the great flood, yet represents God’s blessing in other contexts, as in Leviticus: “I will send you rain in its season, and the ground will yield its crops and the trees their fruit.” This use of complicated symbolism is consistent throughout the Bible. As the literary critic Northrop Frye writes, “There is no image in the Bible which does not have both an apocalyptic and a demonic context.”

Creation Cycle, in its symbolism and painterly execution, reveals an artist working as an image-bearer of a God whose creative power is mercurial. The biblical account of creation is never clean and linear. After the creation of idyllic Eden, things quickly turn sour, until eventually God executes a sort of reset with the flood. In Christian terms, many of the Old Testament characters, such as Noah, Moses, and Jonah, figure as prototypes of Jesus: savior figures and harbingers of a redemptive reality. Yet they typically fail in major ways. Furthermore, although Christians have hope in Jesus as the deliverer of an ultimate redemptive state, the earth is still presently in need of restoration. The establishment of a perfect state of being is only promised after the second coming of Christ, which is also preceded by prophecies of destruction. In Creation Cycle, this instability is clearly present, illustrated in the contending energies of rain and fire, and also in the way the painting is organized, where a grid promises structure but elements remain unfinished and disordered. This is a state of creative flux.

Azoulay continues this inquiry into the nature of creation in his painting Round Table with Black Bird [see Plate 2]. This painting depicts a red table top angled slightly upward, displaying a variety of vessels, art-making objects, and abstract shapes. From the left, a hand intrudes to rest on the table, and in the top right corner a black bird perches on an object, the two elements balancing each other in opposition. The hand can be read most literally as the hand of an artist. This is a studio table and the artist is about to work. Whereas Creation Cycle depicts the active and tumultuous process of creation, this is the moment before, when the artist contemplates the materials before him and meditates upon his first move. There’s a palpable sense of expectancy here. The bird is not yet in flight, but perches ready. The objects and materials on the table exist in a state of half-being. The shapes are unrefined, and a few—including a lusciously painted figure eight, or perhaps an infinity sign—have not yet taken shape as anything figurative. The materiality of the paint—the blue wash of turpentine and oil, the juicy brushwork, the falling drips—all contribute to a state of raw potential. This is the dust of the earth from which God created Adam. These are the still waters over which God’s spirit hovered before the creation of the earth. The hand is the artist’s hand, yet, like Michelangelo’s famous hand, it could also be God’s.

In an interview for the catalog of his show Closer to the Sun, Azoulay says, “The struggle or the main challenge…is to know when you’ve finished the paintings…you shouldn’t overcook it. Let it retain a little flavor and aroma; don’t let the vitamins get burned in the cooking. The painting has to remain in the active zone in order to leave room for those who will see it.” Azoulay likens this attitude to Rabbi Nachman’s teaching that “the perfect man is the non-perfect man.” This ability of painting to be “childish” or “like raw meat”—in essence, to embrace its imperfection—drew Azoulay to the material of paint. This attitude finds antecedents in abstract expressionism as well as in more contemporary notions of “bad painting” or “deskilling,” which is characterized by the intentional rejection of painterly skill for expressive or conceptual purposes.

Elements of Round Table with Black Bird recall Willem de Kooning’s abstract expressionism, in which the process of the painting and the particular movements of the painter’s body are visible within the work. In Azoulay’s painting, a blue sheet serves as a backdrop to the table, but halfway down this backdrop dissolves into a mess of streaking oil paint and turpentine. Drips of blue, originating from the figure’s arm, splatter downward. Gravity, materiality, and the artist’s painting process all figure prominently in the drama.

However, Azoulay’s approach to abstraction is distinctly different from that of abstract expressionists such as de Kooning and his peers, who followed Clement Greenberg’s influential modernist theory that art should be about materiality and not representation. Azoulay does not entirely eschew representation, but moves playfully back and forth between the figurative and the abstract. Although he nods toward his abstract expressionist influences, he isn’t afraid to play around with their rules. For example, some of the blue drips at the bottom of Round Table with Black Bird morph into miniature figures falling off the painting, shifting from pure materiality to imaginative representation. In the Closer to the Sun catalog, he says, “I take something [from art history] and I fiddle with it, unpack it, try to connect it in some way…. It’s the most fun thing of all: someone has died and you can make whatever you want of him.”

As he fiddles with and unpacks what came before him, Azoulay is certainly working within a contemporary tradition. His practice has roots in the influential 1978 show Bad Painting at the New Museum in New York, which popularized the celebration of the unrefined. The press release for the show lauds artists who “consciously reject traditional concepts of draftsmanship in favor of personal styles of figuration.” Marcia Tucker, the museum’s director at the time, defined “bad painting” as “an ironic title for good painting, which is characterized by deformation of the figure, a mixture of art-historical and non-art resources, and fantastic and irreverent content.” Azoulay’s work clearly falls within this category. He cites contemporary artists such as Tal R, Dana Schutz, and Neo Rauch as peers with whom he shares a common playful and imaginative attitude toward painting.

Interestingly, even as Azoulay associates himself with this specifically contemporary thread in art, he is more reticent when it comes to identifying as a distinctly Israeli artist. He argues that in the globalized world, artists are more interconnected than ever before—and he is right. However, it is worth pointing out that this embrace of “bad painting” is particularly significant in contemporary Israeli painting. Perhaps this sensibility has found good soil in Israel’s lack of a historical painting tradition, the youngness of the modern state of Israel, or the provisional and chaotic way things function in the country. Although Israel has a storied history, it’s not a precious place—litter is abundant, development sprawls thoughtlessly, and ancient sites aren’t without tacky or commercial or (need I say) overtly political adornment. It’s not surprising, then, that Israeli artists approach the history of painting with some skepticism and irreverence. Ultimately, this stance introduces a vibrancy—as Azoulay puts it, a “post-post-Holocaust” attitude—that breathes new life into the heavy histories of painting and of the Jewish people.

Nachman’s notion of the perfect man being imperfect is aptly illustrated in any number of biblical characters. Azoulay wrestles with this paradox in his painting, taking on the characters of Samson and Jacob in two of his works. These biblical heroes are deeply flawed. At his birth, Samson was set aside as a Nazirite, dedicated to God, who promised that Samson would be his instrument to deliver the people of Israel from their enemies the Philistines. As a sign of his commitment to God, he was never to cut his hair, which endowed him with supernatural strength. But he was deceived by Delilah, who cut his hair and stripped him of his power, and the Philistines captured him and gouged out his eyes. In captivity, his hair grew again, and in a final sacrificial act he pushed down the central pillars of a temple, crushing himself and the Philistines. Likewise, the biblical patriarch Jacob had a checkered character. He cheated his brother Esau of his birthright but still received blessing and protection from God.

These characters act in the space between the sacred and profane, a space Azoulay also occupies, with his conflicted identity as both secular and religious. The central figure in most of Azoulay’s paintings is an artist in a studio. The biblical figures in his works Samson and Jacob allude to that trope through the representation of these characters as solitary male figures in boxy, studio-like spaces. Asked if these figures are stand-ins for himself as an artist, Azoulay replied that they are “myself but not myself.” As images (at least partially) of himself, we can understand the biblical figures as representing a vision of the artist as prophet—not in the sense of one who divines the future, rather as a flawed but holy man communicating between heaven and earth.

In his painting Jacob, Azoulay depicts the patriarch rising from a trap door in the floor [see Plate 4]. Covered in feathers, he ascends a rainbow-colored ladder into a space filled with birds. Geometric shapes depicting the sky cut into the space, their sharp, stenciled precision contrasting with the frenetic grid-work that cages the birds in a pale yellow middle ground. The ladder recalls the Genesis story in which Jacob dreamed of “a stairway resting on the earth, with its top reaching to heaven” on which “the angels of God were ascending and descending.” In this dream, Jacob receives God’s promise that the earth will be blessed through his offspring and that he will return to his land.

Within the painting the dark maroon ground conjures an earthy heaviness, while the light-blue geometric shapes with their streaks of white seem to float. The ladder attempts to connect these two realms—the elemental and the ethereal—but remains stunted in the middle space along with the menagerie of birds. Given that birds move freely between the sky and the earth, imaginative renderings in art and literature often represent them as symbolic intermediaries between the spirit and human worlds. However, the birds in this painting remain static, caught between earth and heaven. They are not in flight, but rather perch on stands and in cages.

Jacob, covered in lushly painted feathers, is clearly aligned with the birds. As a man of divine promise he has a spiritual identity, yet within the biblical narrative we see him weighed down by the mundane—servitude to his father-in-law, conflict with his brother, and a character that is at times both cunning and fearful. Feathers speak of potential and promise, but neither Jacob nor the birds can ascend freely, because of the grid-like cage. They must make do with the slivers of sky cutting into their space. The metaphor of Jacob and the birds can extend to describe the identity of an artist, and even more generally, a spiritual person: we strive for transcendence and may glimpse rays of the eternal, yet we remained caged to an extent—within our studios, our offices, and ultimately our bodily perceptions. But the painting and its metaphor are not entirely tragic; the angels of Jacob’s dream, who effortlessly move between heaven and earth, serve as the unseen antidote to the fixedness of Jacob and the birds.

Samson is also caught between the sacred and profane, as developed in the painting through the alternation of heavy and light motifs. In the center, Samson appears as a ghostly green figure pushing against two blue columns. This refers to the moment of his simultaneous demise and redemption, in which he defeats the enemy and dies in the process. The choice of narrative clearly reflects Azoulay’s interest in the dialectical relationship between destruction and creation, but the painting also explores a frustrated pursuit of transcendence. A vase with oversized branches in the foreground and a painting of a branch in the background echo each other, signaling upward movement. However, the brushwork is thick and clunky, weighing down the objects. Azoulay adds to the sense of heaviness through the muddy palette and meaty paint that clogs the surface.

But then, unexpectedly, Azoulay tempers this atmosphere with delicate washes, atypical of his work. The figure of Samson is rendered in thinned-out, transparent paint, and an airy landscape—a painting within a painting—sits in the background, dominated by an orange, globe-like shape and blue washes of paint. These moments of reprise allow the viewer to breathe and escape the density that defines the rest of the painting. In Samson, the focus on the materiality of the paint widens the focus from the figure to the medium. Here the viewer is confronted with the contradictory nature of painting: on the one hand, paint is pure material (oil and dirt, basically), but on the other hand it is capable of representation and transcendence. It can be both heavy and light, opaque and transparent, murky and radiant, literal and referential. In this regard, the figure of Samson and the material of paint harmonize to remind us of our heaviness, even as we reach upward toward heroism, redemption, and beauty.

The paintings Samson and Jacob present veiled images of Azoulay as an artist and mystic. However, the interrogation of himself—as a painter and a spiritual person—is most explicit in the painting Hilulaha, a work he considers one of his most significant [see Plate 5]. Azoulay explains that the title is a reference to the moment when the soul leaves the body. In Judaism, holy figures are celebrated on the day of their death, rather than their birth. In this painting, the blue dome refers to the grave of a holy man. Azoulay modeled this shape after the graves of important religious figures in Tzfat, the mystical Israeli city in which Kabbalah originated. In this painting, Azoulay is imaging his own shrine. The painting conflates his legacy as an artist with that of a holy man, which Azoulay believes allows it to most effectively communicate the “mix of being an artist and being religious.” The arrogance of this gesture is knowing; Azoulay is satirizing the “ultra ego-trip” of artists who are obsessed with their legacies and personal mythologies.

However, the painting is also sincere. Without taking himself too seriously, Azoulay acknowledges his role as an artist who communicates truth, not unlike a prophet of the past. He can laugh at himself, but essentially he believes painting to be a place that God “put me in to do something.” He continues, “I feel that [God] is with me,” within “my position as an artist, my influence, the subjects and ideas that I am bringing to my art.”

Spiritual knowledge closely aligns with self-knowledge in this painting, and throughout Azoulay’s work. In the acknowledgements in his catalog for a show at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, he thanks God for “leading me to myself.” In Hilulaha, he interrogates himself through the sketches that are taped onto the blue shrine. These pictures within the picture (another consistent element in his work) depict his face from various angles. Covering the tomb with self-portraits underscores that this is a memorial to himself, complete with candles at the base of the tomb. Although this is self-aggrandizing (and aren’t most creative efforts, which attempt to immortalize one’s personal experience?), it’s also self-critical. The black-and-white drawings and sober expressions alternately recall newspaper images, police sketches, or assignments for an introductory drawing class. Emphatically, this shrine doesn’t represent Azoulay in idealized terms. Rather, it’s a symbol of the honest investigation of himself as an artist—a pursuit that typifies his body of work and ostensibly will mark his creative legacy. It’s this investigation that defines his painting and his vision of spiritual knowledge. It’s a pursuit in which he alternately presents himself as a child and prophet, as a destroyer and creator, and most essentially, as an artist in the image of the God prodding him onward, toward himself.