Alyssa Sakina Mumtaz is an interdisciplinary visual artist and educator working at the intersections of abstraction, sacred geometry, contemplative practice, and craft. Her work is exhibited and collected internationally and has been supported by grants and fellowships from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, the Mass Cultural Council, and the New York Foundation for the Arts. She lives in Williamstown, Massachusetts, with her family.

Image: Your work weaves together references to both American and Islamic craft and visual art. Could you talk a bit about where you grew up and your religious and cultural landscape?

ASM: I grew up on a small farm in Maryland. I was raised outside of the framework of religion but absorbed my parents’ nostalgia for rural American traditional culture. Being fascinated by early America and the idea of “living history,” my mother taught herself to spin, knit, weave, and dye fibers. Throughout my early childhood she worked as a textile demonstrator at a local children’s history museum, where I learned to weave on an enormous two-hundred-year-old floor loom. Looking back on these early experiences, I can clearly see the origins of my desire to jump over the generational ruptures that leave many of us feeling isolated from a deeper sense of tradition and identity.

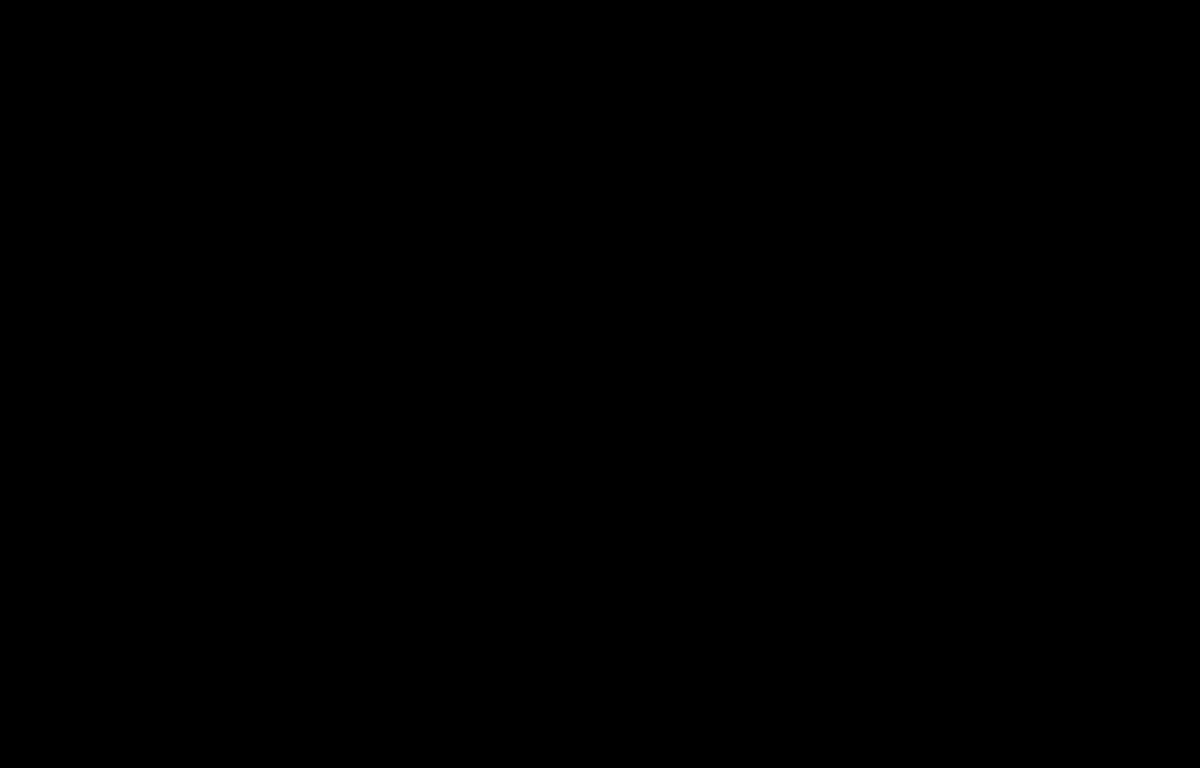

Alyssa Sakina Mumtaz. Portal, 2021. Colored pencil, opaque watercolor, and collage on handmade cotton rag paper. 52 x 32 inches. All images courtesy of the artist.

Image: What were your first encounters with Islam like, and how did your decision to become a Muslim come about?

ASM: My first encounters with Islam unfolded through relationships—initially with my husband, a lifelong practicing Muslim born and raised in Pakistan, and later through a community of Muslim friends who guided and supported my transformation. On my first trip to Lahore in late 2009, I made the spontaneous decision to enter Islam while visiting the shrine of Miyan Mir, a seventeenth-century Sufi mystic. The barakah (blessing) of this early contact with the Sufi devotional ambiance has stayed with me over time.

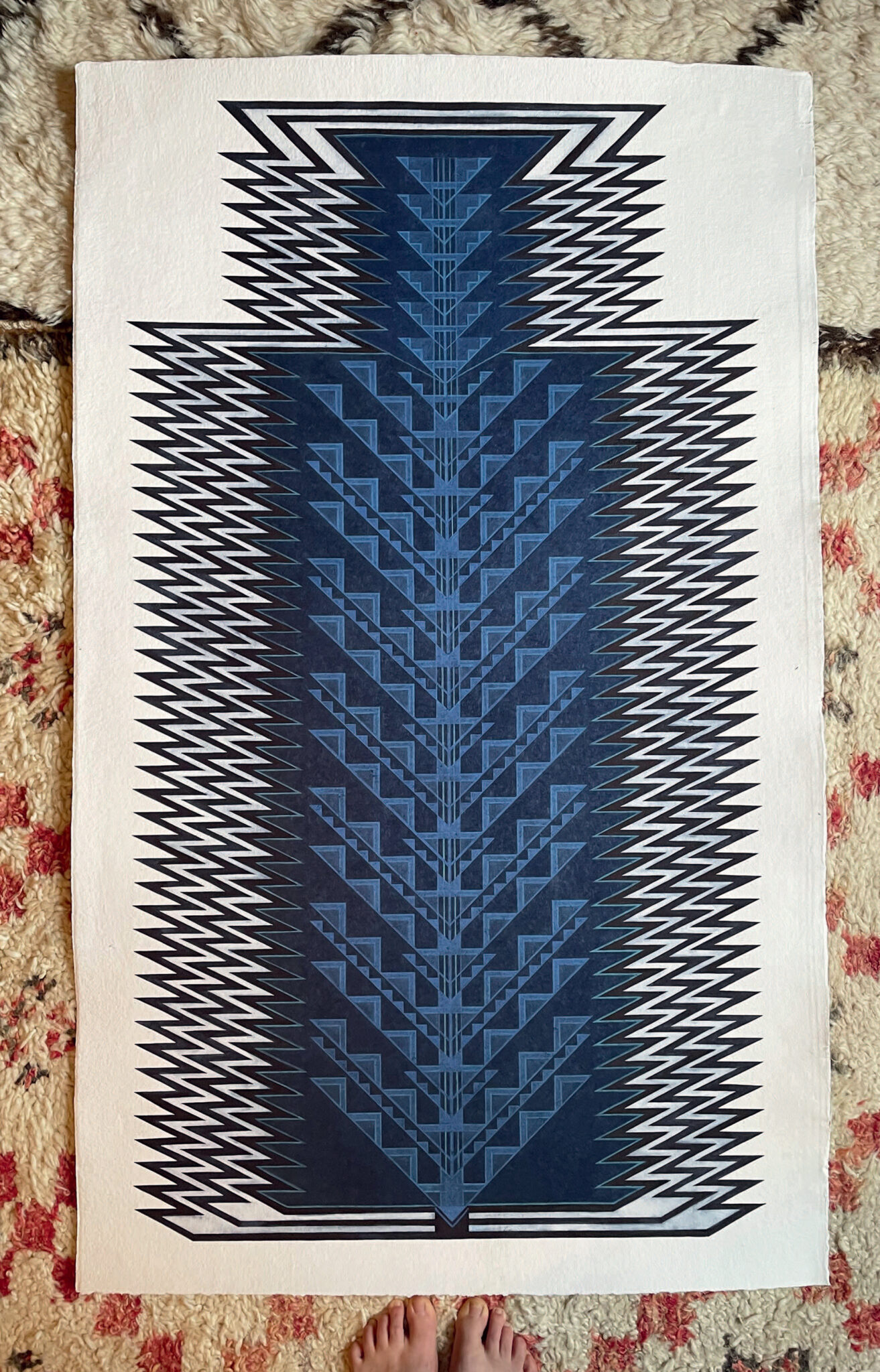

Alyssa Sakina Mumtaz. Traveler (All Saints), 2015. Handmade paper collage mounted on handwoven tussar silk. 72 x 50 inches.

Image: I’m interested in how that faith journey intersected or intertwined with your artistic path. When did you find yourself bringing motifs from Islamic sacred geometry into your work?

ASM: Sacred art offered me a profound early entry point into understanding spiritual practice. At the same time, engaging with its underlying philosophy precipitated a personal crisis. In the transitional period following my conversion, I kept my Islam mostly hidden, mainly because I wanted to shield it from misunderstandings that might throw me off course. Around 2013, I started to allow Muslim iconography to openly assert itself in my work. Constellations—a series of intimate paintings on paper depicting the fluctuations of a single strand of Muslim prayer beads that I use daily—was the first project in which I attempted to represent the contemplative core of my spiritual practice. This body of work was also simultaneously a love letter to the many other religious traditions that utilize beads as a support for prayer. Engaging with the imagery of ritual paved the way for my embrace of sacred geometry, which became a more fully realized branch of my practice during the pandemic.

Alyssa Sakina Mumtaz. Constellation (Broken Mala), 2018. Twenty-four-karat shell gold on handmade indigo wasli paper. 21 x 15 inches.

Image: How did you find viewers responded when these elements first started appearing in your work? Did you find you had to play the role of translator in some way?

ASM: Working through spiritual transformation in a semi-public way has been difficult at times, especially when playing the role of translator means defending the faith—or fending off the misguided idea that religious conversion is a form of cultural appropriation. In the secular social circles that I travel in here in the US—particularly the contemporary art world and academia—lived religious experience is a form of otherness that rarely gets the opportunity to speak for itself, unencumbered by politics. However, I have received a lot of support and encouragement when my work has circulated in Pakistan, India, and the UK—perhaps because religious expression is a less alien phenomenon there.

Image: We started by mentioning how you bring together traditional American and Islamic motifs. That comes out most in some of your textile pieces, which recall early American quilt designs and take the form of Islamic prayer mats. At a formal level, which motifs struck you as most adaptable and expressive across and between traditions? Were there specific regions or periods of American and Islamic design that particularly inspired you?

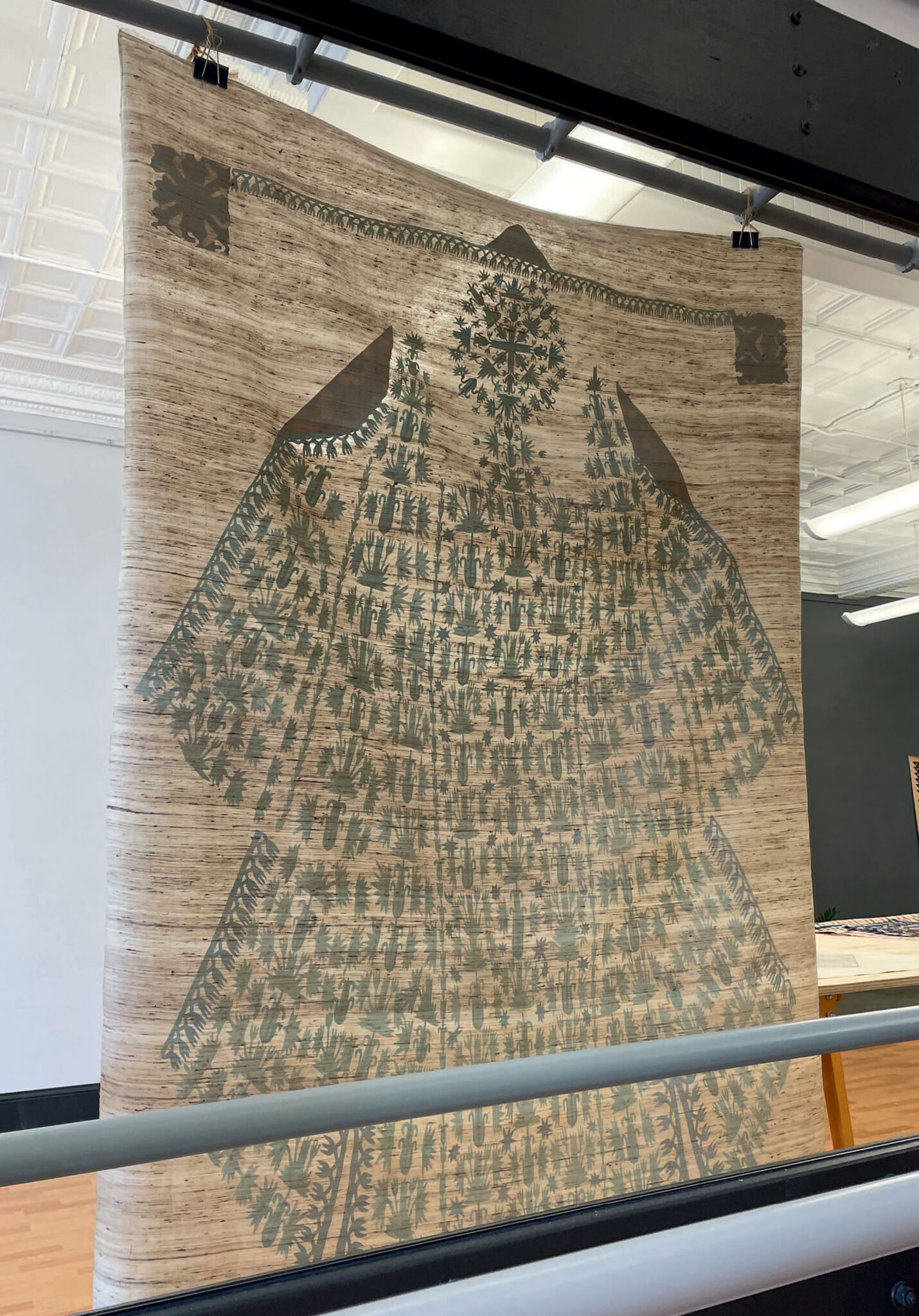

Alyssa Sakina Mumtaz. I Have Been a Portal Twice (Hadi and Jahanara), 2021. Colored pencil on handmade indigo wasli paper. 22 x 15 inches each.

ASM: When people think of Islamic geometry, very often they envision complex, twelvefold star patterns intersecting with biomorphic arabesques and other mindboggling feats of abstraction and resemblance. As much as I admire these possibilities within Islamic visual culture, my current practice draws from the multivalence of simple constructions—namely, crosses and the eightfold stars that proceed from them. I love that these forms are transcultural (appearing independently in many contexts), richly associative, and open to metaphysical interpretation. When I look at iconographic resonances between a traditional star quilt and a central Asian tribal prayer rug, I take it as one more proof that geometry, having no subjective, human author, is the underlying framework of divine manifestation. At some point, one must seriously ask, why do I see stars and crosses everywhere, across traditions? I would answer that these forms are anthropomorphic as well as cosmological, spatial as well as abstract. I look at so many things from various traditions, but recently I have been paying special attention to early American star quilts, the esoterically “revealed” gift drawings of Shaker women, and variations on the Indo-Persianate Hasht Behesht (Eight Heavens) architectural plan.

Image: Do you use any of the works you make in the home, or are they primarily destined for exhibition? How do you go about constructing sacred space in a domestic versus a gallery context, and what—if any—overlaps do you see?

ASM: After my children were born—and during the darkest days of the pandemic—I started thinking much more seriously about the boundaries of my life and what I hope to leave behind as a mother and artist. It occurred to me that the material archive generated by years of exhibition-making might become a burden for those who come after me. Bearing this in mind, I have consciously shifted much of my practice toward functional aims—namely, making art objects that serve a concrete purpose in the here and now of everyday life. The woven rugs and quilts that I make are meant to be prayed on and used in other practical ways. Anchored in geometry, my current drawing practice is alternately a form of study, a meditative exercise, or a design process.

I would never rule out the importance of exhibiting my work in public settings—bearing witness is an important dimension of how I see my vocation as an artist—but I do not prioritize public works over things that are more private, domestic, or ritual in character. Bringing these latter works into public space is a compelling but tricky endeavor. Recently, while exhibiting a quilted prayer mat at an art gallery in Karachi, I realized that it is almost impossible to hold space for the sacred unless a viewer is receptive to that dimension of the work—even in a place like Pakistan, where religion is such an assertive part of daily life. As much as one might try to include other people in one’s worldview, they ultimately bring their own values and expectations to the experience.

Image: If you had to imagine the ideal setting for exhibiting your work, what would it be? And what kinds of spiritual responses might you hope to invoke in viewers?

ASM: Viewing art is the closest many people will come to having a contemplative experience. I am fascinated by the encounter between artists, artworks, and receivers, but I struggle with the conditions in which these encounters usually take place: emptied out, characterless gallery spaces; spectacle-like presentations that suggest entertainment rather than introspection; the cold, hard edge of capitalism. Instead of isolating my work from the various streams of spirituality, history, embodied knowledge, and lived experience that inform it, I want to be as generous as possible with viewers to ensure that they will truly receive something from me. I always welcome the idea of exhibiting my work in unconventional spaces that reflect the textures of my life—a barn, a decommissioned church, an historic rural home—as well as scenarios in which my practice might be understood alongside the frameworks and testimony of sacred art. If an encounter with my work helps a person’s mind become quiet—even if just for a few moments—that is enough.