HOME is always a fraught subject. Even when remembered as a place of unalloyed happiness, it’s inevitably haunted by our sense of mortality, fragility, and loss. Home is also a marker in time, a moving target troubled by hurts and failed hopes—by our longing for future or imaginary destinations.

America itself is a home, of course, but a complicated one: home to immigrants, to the formerly enslaved, to once prosperous or privileged whites. And before all that, it was home to First Peoples, a home invaded by interlopers who stole, broke treaties, and then told stories valorizing those deeds.

Home is often situated in a wishful or remembered story—and memory always includes an element of fiction. We each narrate our lives with a mixture of memory, imagination, self-glorification, and regret. Our collective stories are no different. The tangle of narratives around America as home are the subject of Bill Franson’s recent series of photographs.

Franson’s Mason-Dixon: American Fictions casts a searching and loving eye on a region marked by the smoldering memory of racial violence and economic hardship—while also simply delighting in the visual surprises and paradoxes that litter the Mason-Dixon landscape. Historically, the Mason-Dixon Line demarcates “Dixieland” from the North. That Dixieland is embedded with the memory of African enslavement. In places, it still celebrates heroes of the “lost cause” of southern sovereignty. More wonderfully, it is home of the blues.

The line was originally surveyed by Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon prior to the Revolutionary War to resolve overlapping English land grants given to the Penn and Calvert families. It extends east to west, dividing Pennsylvania from Maryland and West Virginia. Near the Atlantic, it turns south, running between Maryland and Delaware. The line itself was conceived as a means of establishing personal property and reinforcing a boundary—a concept largely foreign to the Susquehannock and Lenape peoples native to the region. As the two men began their research, Mason visited a site near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where twenty Susquehannock men, women, and children were massacred in 1763 by a violent settler group called the Paxton Boys. In the centuries since, other, more surreptitious lines have been drawn for the sake of preserving the property values of the prosperous—like redlining and similar means of segregating the poor.

Though the Mason-Dixon Line was always about protection of white property, ironically, the white world of Franson’s photographs is not a prosperous one—its current denizens don’t seem to own much of anything, much less huge tracts of real estate.

Franson describes his ongoing project this way:

Curious to understand the history of the Line, I have been spinning circles above and below it, poring over maps, sniffing the wind for revelatory suggestions of original intent, evidence of human fortune, misadventure, and borderland whimsy. I am piecing together a collection of Mason-Dixon ephemera—visual fragments of life on the Line.

Image after image combines subtle wit with rich tonal contrasts in ways that belie the often forlorn subjects. This is a place of ghosts and unfulfilled dreams, but also of surprising beauty.

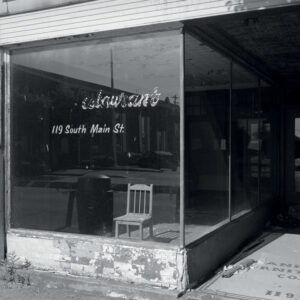

In an image flatly titled Masontown, Pennsylvania, the photographer places the viewer before an abandoned restaurant (one of many in the region) with trash in the doorway, worn-out signage, and peeling paint. Paradoxically, in a scene where we can’t avoid evidence of economic and social decline, we’re also offered visual delectation, in the rich contrast between the bright exterior surfaces and deep shadows behind the glass. An empty chair keeps vigil inside—sunlit and solitary, juxtaposed with a trash barrel reflected in the dark glass. An unlikely pair, the two objects, alike in scale, seem to occupy a shared space—that is, until you notice the chair’s shadow on the floor behind it. The chair is cut off from the world outside, underscoring the isolation of these forsaken spaces. In a contrasting image, Franson chooses a gun shop in the same town. It sports fresh paint, a clean façade, and the proud “Fort Mason” moniker (a reference to a local Revolutionary-era blockhouse). The same little building houses a tanning business and “full service pet salon”—one of many images combining ominous and frivolous aspects of borderland culture.

In another Masontown image, we face a doorway with “Welcome to Ben Franklin” emblazoned over it. Below, a “closed” sign hangs slightly askew, and bits of cardboard litter the floor behind the glass doors. Reflected in that glass is the town’s name in reverse—perhaps suggesting that the reversed fortunes of this place (a town once proud to drop the name Franklin) are always hovering just behind the commercial signage.

In Off Route 14, West Virginia, a “Jesus Loves You” sign and Confederate Stars and Bars are pinned to a sagging clothesline alongside Our Lady of Guadalupe in a holy nimbus. The image is carefully composed: the powerlines and leaning post create a set of diagonals that echo the Confederate flag, subtly gesturing toward the fallenness of that symbol. In the middle ground, the textured lights and darks of the vegetation are lushly rendered in the gelatin silver print. As in many of Franson’s photographs, aesthetic richness is juxtaposed with raw or contradictory imagery.

In Jackie Lee, Brownsville, Pennsylvania, Franson serves up a feast of close gray tones. An emaciated man in a Steeler’s cap stands facing us, his hands clasped almost shyly before him, the hint of a smile on his weathered face. An old-fashioned confectionary sign hangs in the blurred background, a faded promise of now-lost sweetness. There’s more than a hint of irony here: despite the cap, the man clearly derives no material benefit from the NFL’s massive profits, nor from the steel industry that was once the economic backbone of the region. There’s a wistfulness in the photograph, and an affection for its subject—even as the image quietly gestures toward photodocumentary of yesteryear on the injustice of the steel mills and robber barons.

That combination of quiet longing and tough-minded critique is one of the most compelling aspects of Franson’s oeuvre. Though social criticism is close to the heart of his work, he stops short of a polemical edge. There’s an unmistakable pointing toward economic losses and concomitant corporate responsibility, but with an equal measure of aesthetic contemplation for its own sake. For instance, in Clairton, Pennsylvania, a lone headstone marks a grave in an overgrown cemetery. Its names and dates are indecipherable, scoured away by acid rain from the factory smokestacks framed in the background. But before we grasp the environmental cause and effect, the rich tonalities are what first capture the eye. We linger over the lights and darks of the leaves, the subtle striations and textures of the grave marker, the careful composition. You might miss the politics entirely if you were simply enjoying the aesthetics. But Franson inexorably draws the eye to that gap in the trees, those blackened chimneys. Social critique and sensory delight are held in a strange tension.

Though influenced by photojournalism, Franson’s American Fictions point beyond the present political moment toward the perennial struggles and moral contradictions of being human. The images gesture toward environmental degradation and economic strife, but they do so in subtle ways, avoiding obvious tropes like shuttered factories, collapsed hillsides, and suffering children. Rather than telling us what to think, he sets us down in a scene, invites our meditative gaze, and lets us draw our own conclusions. By avoiding straightforwardly message-driven images, he gives us room to see our own complicity in this degradation. (And who among us is completely innocent of the desire for cheap energy and cheap, imported consumer goods?) He also leaves us room to see occasional signs of hope—often in the least obvious images.

For example, in Quantico, Maryland, we are treated to a velvety-dark tree that casts a spreading shadow in the foreground—yet the main subject is in the mid-distance: a brightly illuminated tumbledown building. Quantico is a counterpoint or reversal of another photograph, Methodist Church, Columbia, Delaware, of a beautifully maintained church with a prominent stump in the foreground. Despite their opposite imagery, both pieces evoke a kind of perseverance. In Methodist Church, the building itself conveys steadfastness and strength—a veritable symbol of “home” is revealed in this prim little church—and yet the foreground tree is missing, felled. The tonal cast is spare and striking. Lit like a Bergman film, the solid structure signals resilience. In Quantico, all that is reversed: the backlit tree signals vitality and perseverance, while the house is leaning and crumbling.

Bill Franson’s images of the present-day Mason-Dixon Line region blend a sense of melancholy with aesthetic enjoyment. He gives us the pleasure of those velvet darks juxtaposed with crisp raking light; the surprise of discovering visual “rhymes” in commonplace settings; the joy of form, space, and composition employed for their own sake. He makes use of all the tools image makers have to delight us, while simultaneously inviting us to take stock of the social inequities and contradictions that haunt this region. And this tension—between aesthetic contemplation and journalistic truth-telling—is, I believe, the engine of meaning in his work. His faith (an unorthodox, Wittgenstein-inflected Christianity) is nowhere foregrounded but simmers in the background, the source of an unerring eye that sees what is present and what is missing. He perceives both the beauty and the problems besetting a region whose former prosperity was built on the backs of slaves and indentured workers.

Perhaps the word “fictions” in the series title is a giveaway. In his work, the fond imaginings of southern lost-cause heroics give way to a hard-edged realism that is only softened by the beauty of the images. Another possible fiction the artist points to is that of e pluribus unum. The dream of a “more perfect union” hovers both north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line, but without the righting of persistent wrongs, it will never be more than a dream. And although Franson’s images are from Pennsylvania, the Mid-Atlantic, and southward, if folks in other regions are tempted to think they’ve escaped the contradictions at the heart of this country, they need to think again. If we are to be one-from-the-many, there must be a reckoning—in terms of race, equity, fair housing, health care, and honest governance.

The ethical dimension of Franson’s work is subtly communicated. Free of bombast or didacticism, his vision is steeped in philosophical complexity and emotional honesty. His masterly handling of visual paradox and rich tonal textures gives his work gravitas despite the humble, even pedestrian subject matter. His work participates in the legacy of great photodocumentarians like Eugene Smith, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank, alongside more recent image makers like Rena Effendi and Dina Litovsky.

Home is a fraught concept—and in Franson’s photographs, the fragility of our larger home, the earth, is evident in felled trees, belching smokestacks, and shuttered towns eviscerated by powerful corporate interests that ignore the plight of the planet and its inhabitants. Quietly crossing Mason and Dixon’s line, Franson reveals the complex texture of our sense of home, even as the messy, contradictory nature of our American life continues to unfold.

View the complete Mason-Dixon: American Fictions series and more of Bill Franson’s work at www.billfranson.net.

Bruce Herman’s paintings are in the collections of the Vatican Museum in Rome, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and the Cincinnati Museum of Art. His writing about art has appeared in Image, Books & Culture, Comment, and several books. www.bruceherman.com