Recently appointed director of programs for the Foundation for Spirituality and the Arts, Leeza Ahmady is internationally recognized as a curator of exhibitions, festivals, and experimental educational forums. She has also led Asia Contemporary Art Week, the premier US platform for artistic dialogues from all regions of Asia since 2005.

Image: Can you talk a bit about your background growing up in Afghanistan? What kind of art were you exposed to?

Leeza Ahmady: My exposure to the arts began through the great tradition of storytelling. I grew up captivated by epic tales from the Qur’an and the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), as well as Sufi poetry recited by my mother, herself a poet descended from a line of poets. I listened to classical South Asian and classical Western music on the radio with my father, a lover of mathematics and avid gardener. There were also daily philosophical and political debates between my parents, giving me an intense awareness of the interconnectedness of the world, in which I was just as powerfully at its center as anyone else.

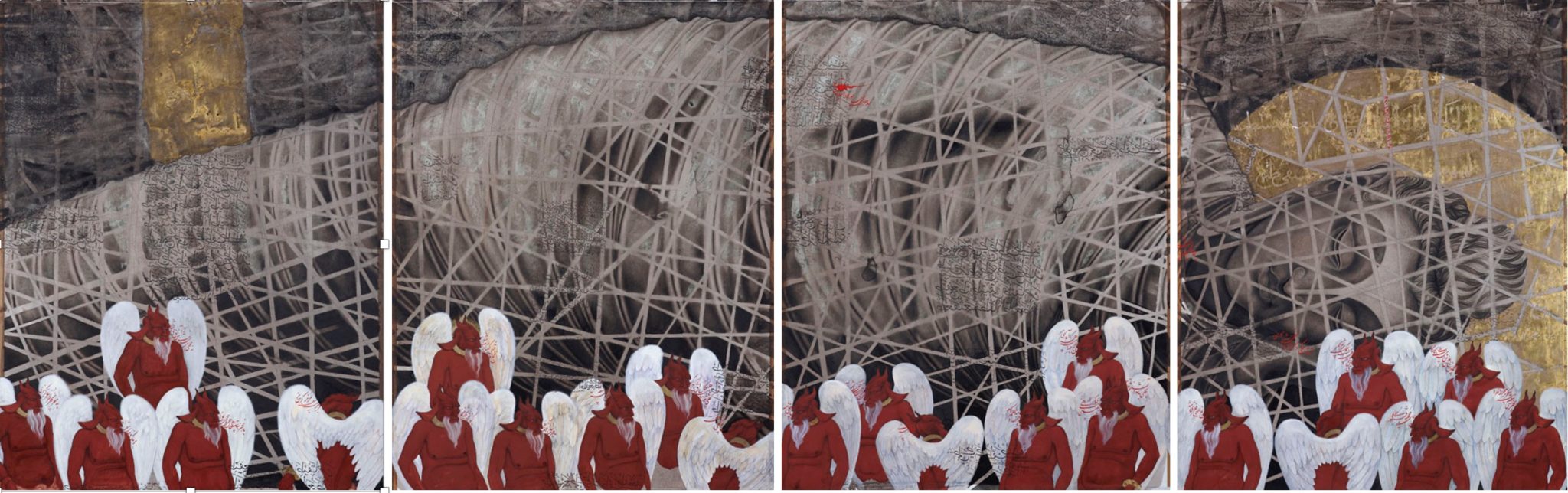

Khadim Ali. Haunted Lotus, 2012. Four panels, 29½ x 22 inches each. Watercolor, gouache, and ink on wasli paper. dOCUMENTA(13) exhibition, Kassel, Germany, 2012.

Image: The Taliban’s last regime infamously destroyed the Buddhas of Bamiyan and suppressed almost all art. What challenges do curators and artists face right now in Afghanistan, and how might people help?

LA: Afghanistan’s arts sector, like those in many other places, has been subject to the whims of one regime or another. There is a focus on the Taliban’s repressive rule in the 1990s, but artistic repression didn’t just spring out of nowhere. It began with the fall of the monarchy at the hands of the socialist-communist government, which led to the Soviet invasion in 1979. This was followed by two decades of brutal civil war financed by the United States and other Western powers—at the cost of millions of Afghan lives and millions displaced—a period during which Afghan resistance to Soviet occupation helped finally bring about the end of the Cold War. People in the West seem unaware that it was the orphaned or abandoned boys growing up in refugee camps, caught in the clutches of violence without the soul-nourishing love and wisdom of their mothers, who helped foster the Taliban in the first place.

Mariam Ghani. A Brief History of Collapses, 2011. Video still, 22:00 minutes. Modern Mondays screening at MoMA, Asia Contemporary Art Week, New York, 2011.

So this moment for artists is part of a recurring nightmare. They are dismayed that after twenty years of working to build a society that is representative of Afghanistan’s diverse artistic and cultural life, they now face what none imagined they would again. The word “challenge” barely applies to their situation. Repressive policies and persecutions aside, they are dealing with a threat to their basic survival. As you and I speak, a month after the shockingly hasty American and international withdrawal, the economy has collapsed. Afghan artists supplement their art practice by holding jobs in culture and education. Many are unable to work or receive salaries, because all mechanisms in society have come to a halt.

Some people are concerned about protecting artworks at the National Museum in Kabul. I respect their mission. However, we should be concerned about living artists who want nothing more than to live and breathe their art. We must recognize that the art world is a “glocal” community, because artists everywhere contribute to its ecology.

The US and international art communities can act by exerting pressure on politicians to remove the impediments that stand in the way of immediate asylum for artists. We need them to donate money towards visa fees, offer invitations for residencies, write support letters, create university or other art positions, and obtain legal and financial support for those who need to leave Afghanistan right now.

Almagul Menlibaeva. Turanic Totems, video still from Apa, 2003. 9:47 minutes. Tarjama/Translation at Queens Museum, Asia Contemporary Art Week, New York, 2009. All images courtesy of their respective artists and Leeza Ahmady.

Image: There are a lot of misperceptions about the role of art in the contemporary Islamic world. What do you think might surprise people about the art being produced in central Asia right now?

LA: I have often said that contemporaneity—much like modernity and creativity—does not belong to one race, place, or economy. Art in central Asia has unfolded in parallel historical timelines to that of other regions. And it looks much like art made elsewhere. The best of it references the region’s cultural, aesthetic, spiritual, and historical specificities. Since the incredible critical acclaim that greeted the first Central Asian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2005, artists from Afghanistan and the post-Soviet countries of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan have drawn increasing attention from Western curators, museums, and galleries. Much of that attention has centered on the region’s remarkable single- and multi-channel video works—a strength often attributed to the region’s centuries-old nomadic, shamanist, and Sufi rituals and traditions of storytelling, street theater, and weaving.

Image: You recently became director of programs at the Foundation for Spirituality and the Arts, a nonprofit organization founded in 2021 by Tyler Rollins. What do you think is missing in conversations in this area, and what do you hope to add?

LA: For centuries, art and religion in the Western world were inextricably linked, with faith providing a bedrock for artistic practice. Today, that seems almost unfathomable. FSA was founded to address the marked lack of support for the creation and dissemination of spiritually oriented art and its discourse in the US contemporary art scene. Creative works have much to gain from religious inspiration, just as religion has much to gain from art and aesthetics. We aim to reignite the dialogue between the two realms while fostering community through residencies, exhibitions, gatherings, and fellowships to inspire a more conscious and fulfilled life.

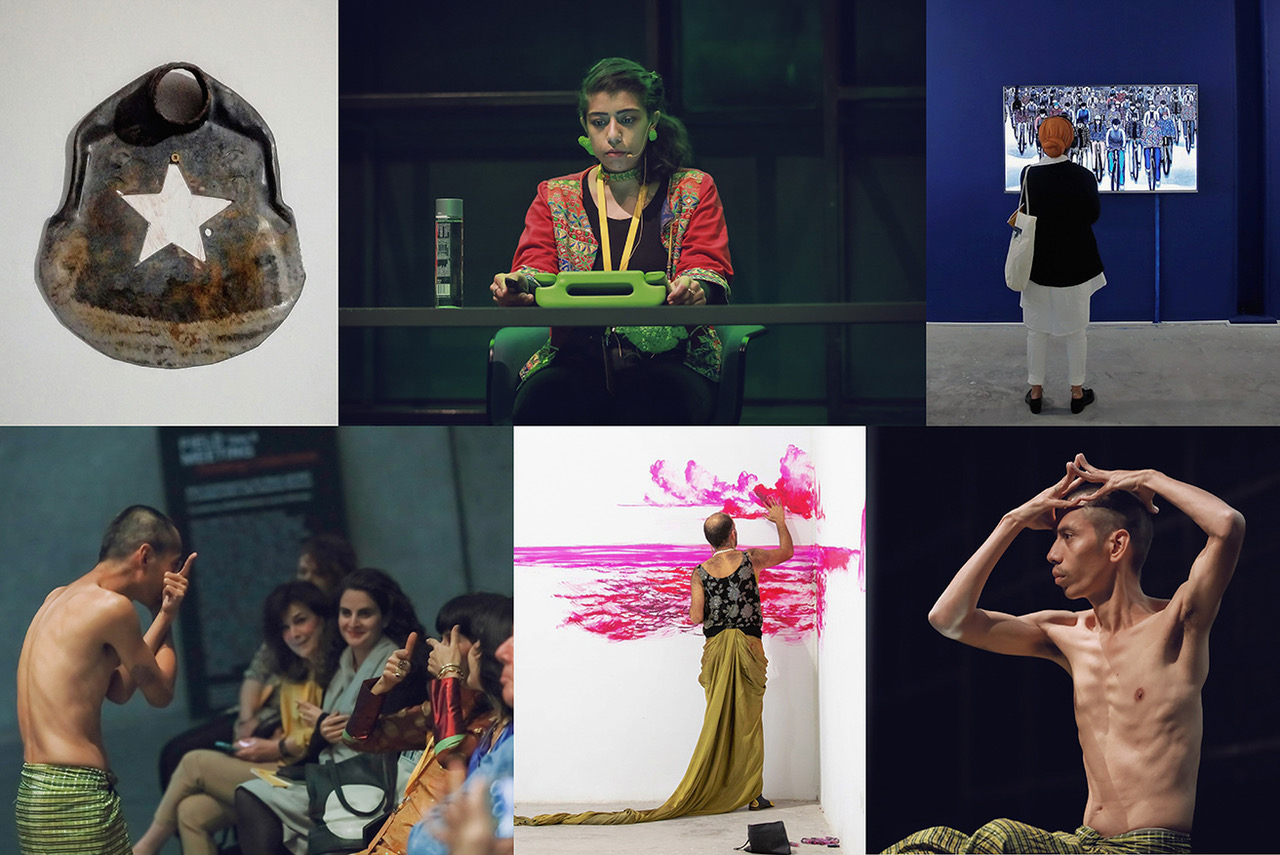

Field Meeting Take 6: Thinking Collections—art forum performances, pop-up projects, and lecture-performances with 30 Asia-based artists and arts-professionals hosted at Alserkal Avenue, Dubai, UAE, Asia Contemporary Art Week 2019.

Beyond exhibition-making, my curatorial work, especially with the Asia Contemporary Art Week platform, has focused on highlighting the journeys of diverse art practitioners over time and supporting the profound processes that they engage in. I am thrilled to delve into the connections between artistic practice, spiritual community, faith, and conscious living through programs that empower artists to expand their being and the life force within the communities they traverse.

After the events of the past year, our cultural need for community has become abundantly clear. Paying attention to the spiritual can unite us—it’s a vital means of reaching beyond the material and connecting with our neighbors. What better way to do that than through art, a physical form that expresses the intangible, unifying experience of what it means to be alive? As my colleague Tyler Rollins notes, “A focus on transcendence and orienting oneself to a higher power can be a source of insight, illumination, and inspiration—all things that are also associated with artistic expression.” FSA’s programs will activate neglected, meaningful dialogue and collaboration between faith-based and contemporary art communities.

The Asia Contemporary Art Forum recently launched a fundraising campaign to help resettle Afghan artists and cultural workers at risk.

Asian Contemporary Art Week’s YouTube channel is a resource to learn more about the program through its presenters’ work. Here, we’ve assembled a video starter kit from ACAW’s annual forum, FIELD MEETING Take 6: Thinking Collections, hosted at Alserkal Avenue, Dubai 2019:

+ Umber Majeed | Atomi Daamaki Mohabbat (The Atomically Explosive Love), Lecture / Performance

+ Nikhil Chopra | Rouge, Performance

+ Moe Satt, F n’ F (Face and Fingers), Performance