Shahed Saleem is an architect, author, and teacher whose work explores migration and diasporas, in particular their relationship to loss, place, and reconstruction. His drawings and sketchbooks are held in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Image: You created a pavilion for the most recent Venice Architecture Biennale. Can you talk about this work and how it came about?

SS: The pavilion I cocurated for the Victoria and Albert Museum at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2021 was titled Three British Mosques, and it told the story of three mosques in London that had all been created through the adaptation of existing buildings—an eighteenth-century Protestant church, a nineteenth-century Victorian public house, and a 1930s suburban house. We re-created 1:1 replicas of architectural elements from each mosque, showing how the existing architecture had been adapted by the mosque community, in so doing creating a completely new visual culture.

My book on the architectural and social history of the British mosque, published by Historic England, came to the attention of the V&A, and we started talking about how that history could be represented by the museum. The Biennale pavilion was a great opportunity to develop this dialogue, and the museum has acquired elements from the mosques that we displayed.

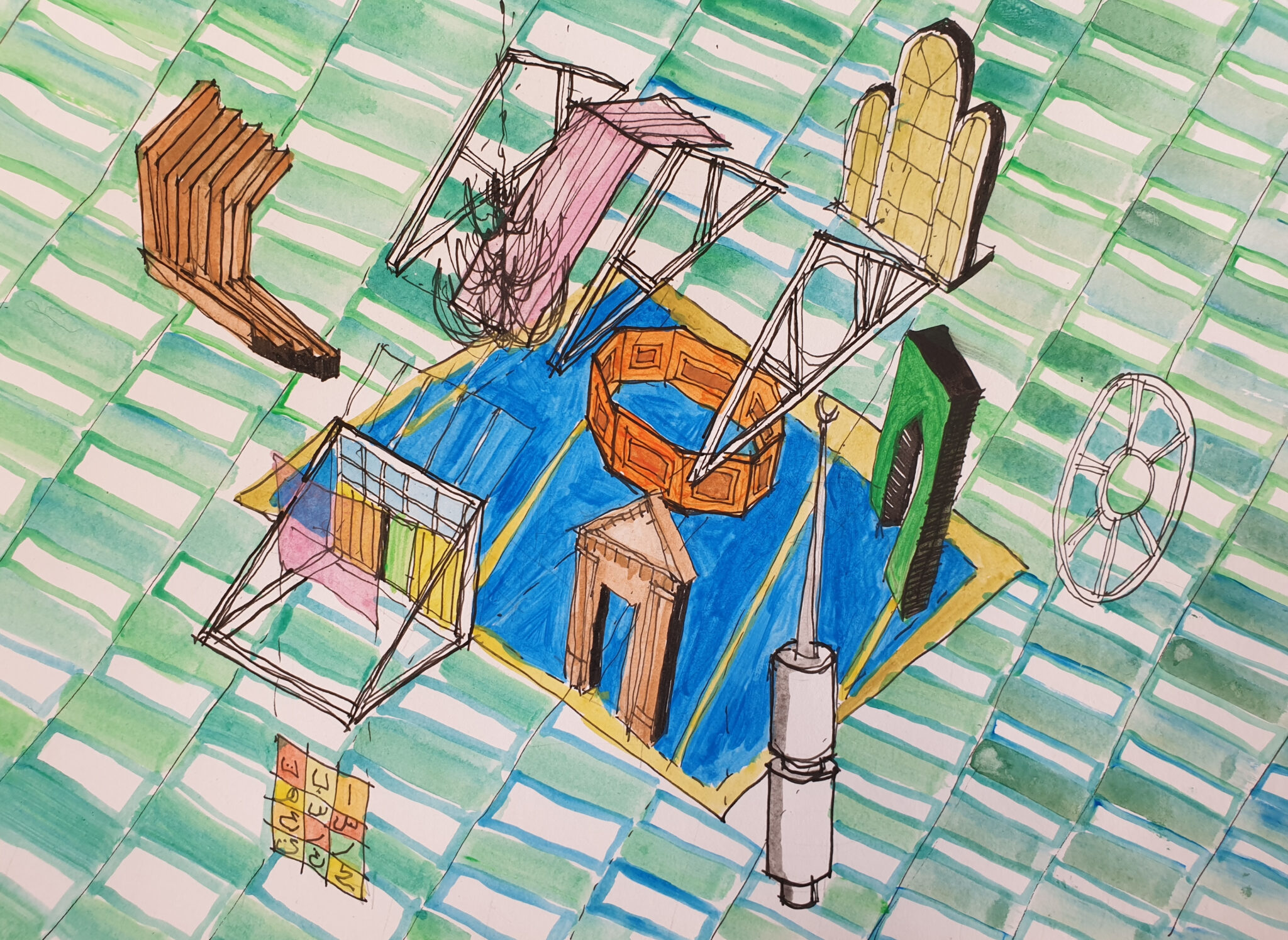

Detail of a concept sketch for Three British Mosques by Shahed Saleem.

Image: Was there anything that you worried over, or thought might risk misunderstanding, as you developed this project?

SS: We saw the work as a way of recognizing, documenting, and celebrating the contribution Muslims have made to British architecture. However, there is a fine line between a meaningful representation of Muslim experience and an exoticization of a less-understood “other.” I feel that since the project came from a place of lived experience and constituted part of a lifelong process of working out an expressive diasporic language, it was sufficiently in touch with people’s experiences. Perhaps the tension between earnestness and fakery even gave the project its energy.

Reconstructions from Brick Lane Mosque, a former Huguenot church, including the female prayer room in the underground vaults and a sundial on the façade inscribed with its inception date of 1743 and the Latin script Umbra Sumus (we are shadows).

Image: You’re an architect yourself and have designed mosques and Islamic community centers in the UK. Why did you choose to focus on the less-heralded forms of adapted mosque spaces? And why these three in particular?

SS: Some 80 percent of mosques in Britain are in adapted buildings. This means that the architecture of the British mosque is being determined by myriad existing spaces, built forms, and visual languages. To me this is a fascinating situation, where the mosque becomes an unexpected architecture, having been designed through a series of improvised and iterative design decisions, usually by the users themselves. I see this as a highly creative process resulting in a radical architecture that breaks established rules of design and taste. I find this exciting from the point of view of design and visual culture, but I also feel there is a certain power in that the diaspora is speaking through its own voice. We chose these three mosques as they each represent a certain type of adaptation: a residence, a former religious building, and a public house.

Reconstructions from the Old Kent Road Mosque. The former dining hall of the Victorian Public House has been given a new visual language to signify it as a religious space.

Image: Do you see parallels between the aesthetic and religious decisions of the Muslim communities you featured and those of diasporic communities of other faiths as they’ve adapted spaces?

SS: Minority faiths in Britain have always started their architectural journey by adapting existing buildings and creating their religious spaces in improvised and ad hoc ways. In this way, the architecture of the mosque is following the architectural history of Catholic, Nonconformist, and Jewish communities in Britain over the previous couple of centuries.

Image: Returning to your own practice, what lessons do you draw, whether stylistically or otherwise, from these kinds of domestic religious spaces?

SS: I’m driven by the question: How do we design new mosques in Britain that are a continuation of the design history laid out by the adapted religious buildings of the past century, rather than a rejection of this history in favor of a set of global Islamic architectural referents? This latter option is becoming more and more popular for new mosques, but I’m most interested in exploring the first option.

The mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca) of the Harrow Mosque, built by a carpenter in Kashmir and installed in the main prayer hall,which was the living room of the former house.

Image: What do you think is most challenging and exciting in mosque design today?

SS: The question of what defines an “indigenous” mosque has recurred throughout the history of mosque design in Britain, and indeed the West more broadly. I think seeking an architectural voice that responds to and represents the complexity of the diasporic condition is still an outstanding and exciting challenge.