Image’s visual art editor, Aaron Rosen, is also cofounder and director of the Parsonage Gallery in Searsport, Maine (www.parsonagegallery.org), a new gallery exploring the relationship between ecology, spirituality, and creativity through contemporary art.

Image: You just launched the Parsonage Gallery this summer. How do you think the art world has changed in recent years, especially since the pandemic?

AR: Well, the art world is a pretty complex ecosystem, with a lot of different species competing for resources and attention. Those resources are relatively scarce right now for public institutions and not-for-profits but comically bountiful for the top commercial enterprises like blue-chip galleries, auction houses, and art fairs.

The endless expansion of the commercial sector benefits some artists, who become darlings of the market, but it doesn’t do much for everyone else (and it’s a mixed blessing even for those artists). It’s also incredibly resource-intensive at every level, including the massive carbon footprint left by myriad art fairs and biennials. In the wake of the pandemic, this is a good moment to step back and reassess what the art world is doing and what can be done to make it more sustainable, equitable, and responsive.

At our gallery, we’re wagering on the importance of spaces that support artists holistically, as creators of value that isn’t simply financial. We’re also betting that dispersed, smaller, site-specific venues will become increasingly important for people who want to make and look at art that’s anchored in a sense of place and community. The overstory of the art world gets a lot of attention, but the most exciting and sustainable growth is really happening at the ground level.

Ian Trask. Portal, 2022. Miscellaneous materials bound in string and monofilament. From the exhibition Out of the Whirlwind. On view at the Parsonage Gallery, summer 2022.

Image: Speaking of place, how has that influenced your vision for the Parsonage?

AR: Well, Maine has a long and fascinating art history, and it’s a privilege to tap into that. There’s an unbroken history of indigenous artists in the state, as well as practitioners of folk art, especially in our area. And a surprising number of modern artists have been raised here, like Louise Nevelson, or made Maine an important part of their practice, like Alex Katz.

But the specific vision for the Parsonage came together more organically than strategically. My wife Carolyn was hired as the priest of an Episcopal church in Maine. Then we happened to find an amazing estate on the coast with a space that seemed destined to be a gallery. It was built in 1831 as a parsonage for an important abolitionist minister, the Reverend Stephen Thurston, and his wife Clara Thurston (née Benson). When we started looking at the local archives, we discovered that Clara was Winslow Homer’s aunt, and he even stayed here and sketched the family cow! With that artistic and religious lineage, the location and the space seemed perfect for a gallery exploring the intersection of spirituality, ecology, and creativity.

Yola Monakhov Stockton. Installation view of Community Garden at the Parsonage Gallery, fall 2022.

S. Billie Mandle. Nitrile Exam Gloves, 2013–19. Archival pigment print. From Blue Ground, on view at the Parsonage Gallery, fall 2022.

Image: You mention that your wife is a priest. And you’re Jewish. Is there an interfaith angle to the kinds of exhibitions and programming you do?

AR: Oh, absolutely. For a practicing Jew married to a priest, religion is kind of unavoidable in our life together, especially in raising our son Jewish. The gallery is very much an extension of that life, quite literally, since it’s based in the carriage house on our property. We work with artists we both feel passionate about, as people and as creators. But that doesn’t mean the artists have to be Jewish or Christian. For example, Güler Ates, from Turkey, is Sufi and Alevi inspired; Dua Abbas belongs to the Shia minority in Pakistan; and Hanae Utamura delves into the Shinto traditions of Japan. What’s important for us is whether artists raise spiritual questions, which initiate dialogue, whether within or between traditions.

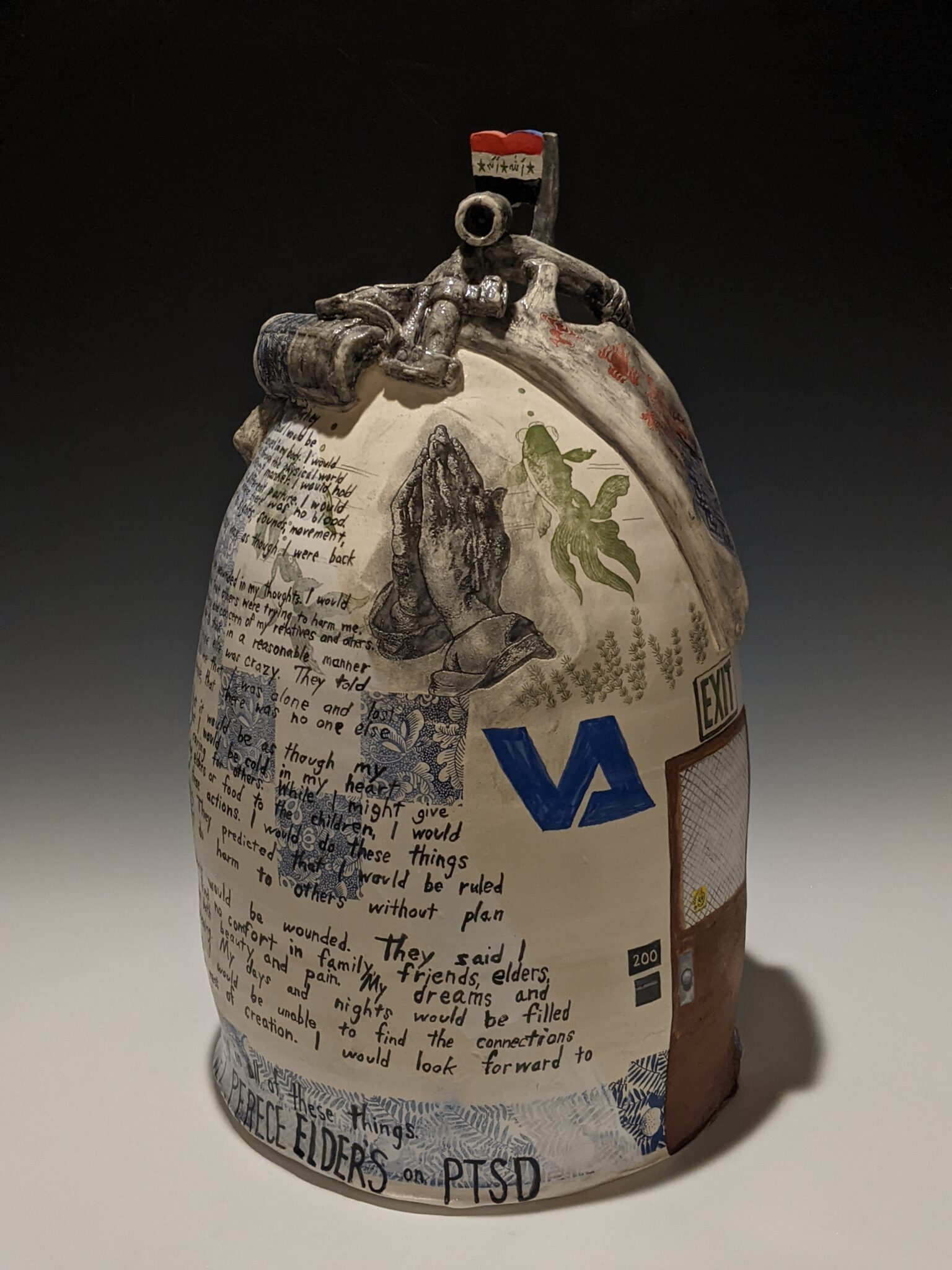

Jesse Albrecht. Room 200, 2021. White earthenware clay with underglaze, decals, and glaze. 20 x 12 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the Henry Luce III Center for the Arts & Religion.

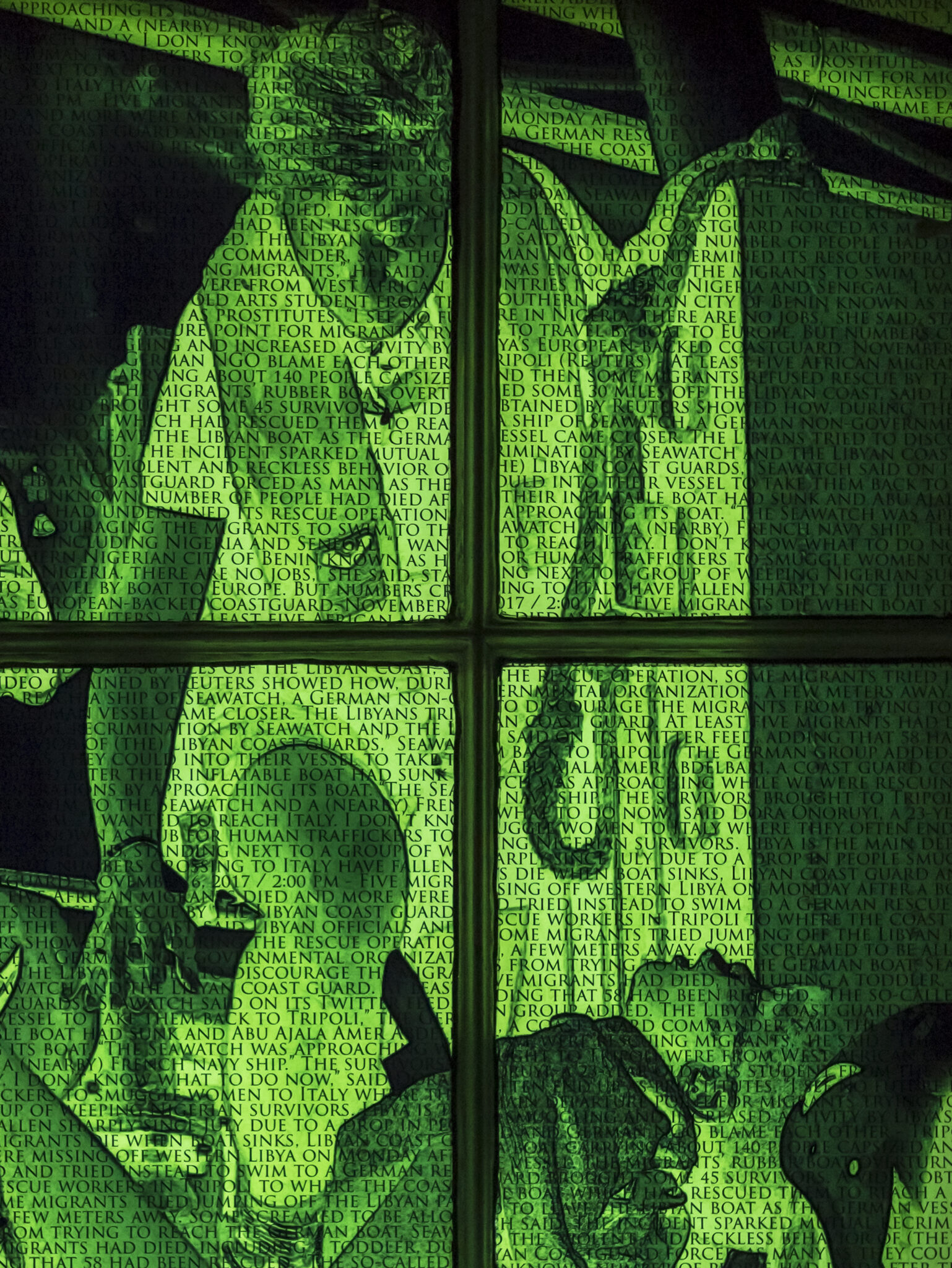

Michael Takeo Magruder. Sea Watch, 2019. Detail of digital “stained-glass” window from a new media installation at the Parsonage Gallery, fall 2022.

Image: When you say ecology is one of your themes, do you mean primarily climate change?

AR: Climate change is a topic a lot of our artists address, whether explicitly or implicitly. And it’s frankly harder to find subjects that don’t touch on this topic in some way, especially here on the coast of Maine, which is warming more quickly than almost all of the world’s oceans.

But we are interested in any juncture at which ecology and community intersect. Recently we had a powerful exhibition called Community Garden by Russian-American artist Yola Monakhov Stockton, which looks at environmental justice and the food deserts created in Buffalo, New York, by racist practices like redlining.

So I think just as we’re stretching what we think of as spiritual, we also want to continue to broaden the scope of environmental issues we address in the gallery. In fact, at their best, both ecology and theology tend to pull the other discourse in new and urgent directions.