Image: Terrence, when you founded the Museum of Contemporary Religious Art, one of your first major shows was about artistic responses to the HIV/AIDS crisis. Can you tell me more about that show?

Terrence Dempsey: Consecrations: The Spiritual in Art in the Time of AIDS was MOCRA’s third exhibition. It opened in the fall of 1994, only about eighteen months after the museum’s grand opening. It came together quickly and really, in a graced way, out of a tragic moment. Juan González, a talented Cuban-American painter with whom I had become good friends, died from AIDS-related causes on Christmas Eve in 1993. I was able to see him in his final days and to share a Mass of healing with him and a circle of family and close friends. Following Juan’s death, my attention kept getting drawn to the fact that a number of artists I had come to know well were also dealing with the reality of HIV and AIDS, and I was seeing some very powerful work done around that reality. Furthermore, a number of Juan’s fellow artists took part in a memorial exhibition for him at Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York. With deep generosity on the part of many artists, gallerists, and private lenders, I was able to organize Consecrations. I wanted to present an exhibition that was widely embracing at a time of great fear and harmful attitudes.

David Brinker: I began working at MOCRA during Consecrations. It made a tremendous impression on me, and on many others. The exhibition generated local, national, and even international media attention. It was also a means of connecting with the St. Louis community, through events such as Day With(out) Art. Even more than the opening exhibition, I think Consecrations helped define what MOCRA was to become.

TD: From the beginning, I wanted to challenge people’s ideas about what religious art could be, to stretch categories and ways of thinking, to show that the artists of our time continue to engage in meaningful dialogue with the great faith traditions—and also that this art is in dialogue with the present moment. It’s unafraid to ask, “Who is my neighbor?”

Image: How does that historical moment, during the terrifying spread of AIDS in the eighties and nineties, resonate for you today, in the midst of another pandemic? Do you think the challenges facing artists and the art world today are similar, or unique?

TD: It’s too early to know, but thinking back to the time when Consecrations came together, I’m struck by the sense of generosity that emerged. Artists were creating art because they needed to, not to please the market or get shown at a gallery. Projects like the AIDS Memorial Quilt brought people together in a common response to a shared trauma. I think we’re already seeing a similar generosity of spirit in response to the new pandemic.

DB: A major change since Consecrations is the advent of social media, which despite our physical distancing is helping us interact with unprecedented immediacy and breadth. Individual artists are creating work in response to this uncertain moment and sharing it online. Museums that have been forced to close to visitors are finding ways to share their collections virtually. Activism and community are happening differently than they did during the AIDS crisis, but I think people are responding with many of the same impulses.

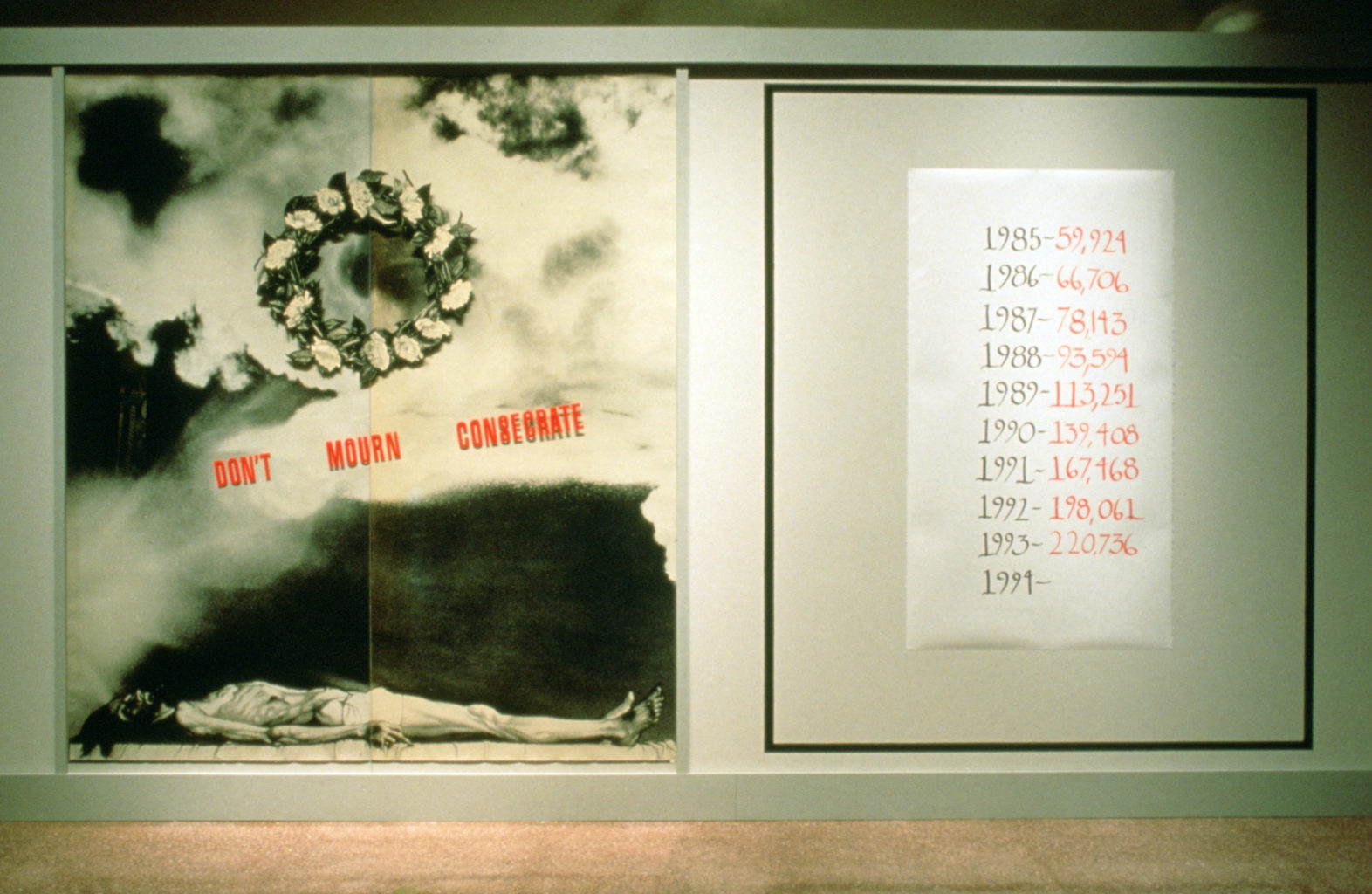

Juan González. Don’t Mourn, Consecrate, 1987. Photo collage with mixed media. Primary artwork: 110 x 97 inches. MOCRA collection. Photo: Jeffrey Vaughn.

Image: Many of the artworks in Consecrations entered the MOCRA collection, representing an important body of work on AIDS. Are there particular works that you think might give people facing the coronavirus a sense of hope or consolation?

TD: Consecrations included work by twenty-eight artists, so it’s hard to narrow that down, but two stand out. There’s Don’t Mourn, Consecrate, by Juan González, which inspired the exhibition title. It was one of the first works of public art to deal with AIDS when it was displayed in the street-front windows of the Grey Art Gallery at NYU in October 1987. In its original installation, it was accompanied by a scroll on which the cumulative tally of AIDS deaths was updated weekly. And now we watch with grief and trepidation as coronavirus infections and deaths mount day by day. By quoting Hans Holbein’s Dead Christ in the Tomb, the work speaks powerfully about the frailty and vulnerability of our bodies, which in Christian faith is something that God enters into. The gathering clouds evoke the unknown impacts of this pandemic looming on our horizon, but there is still light breaking through.

Another work that comes to mind is the sculpture Liturgy by Alec Vargo, a sort of modern-day Pietà, with its depiction of a man standing, holding the slumped body of another. His head is thrown back in a cry of grief, but he is gagged. Originally the work spoke of those who couldn’t publicly mourn their loved ones due to the stigma surrounding AIDS. In this moment when we all must keep our distance and avoid physical contact, when people can’t visit their loved ones in nursing homes or gather for funerals, this work acquires new resonance.

Alec Vargo. Liturgy, 1990. Ceramic with mixed media. 38 x 18 x 19 inches. MOCRA collection, gift of Humphrey Wou. Photo: Jeffrey Vaughn.

DB: For me Liturgy also speaks to frustration with the way the scientific and medical communities have found their voices muted or censored.

Another work from Consecrations that takes on new meaning for me now is Angels in Australia, a found-sound collage by Judy Silver made up of answering-machine messages exchanged with the artist’s dear friend during the course of his struggle with AIDS. We are all coming to appreciate the means we have of instantaneous communication in this time of physical distancing. It’s expanding our thinking about the nature of presence, but we should also be asking how we will be able to preserve, return to, re-inhabit, and reinterpret those virtual interactions in the future.

Image: As a museum director and curator, David, what do you think are the main challenges for MOCRA at the start of what feels like a (rather terrifying) new era?

DB: I hesitate to venture guesses too far into the future, but it certainly feels like we are poised for some seismic shifts. As an academic museum, MOCRA is somewhat insulated from the existential threats faced by many small museums and cultural centers, but I’m sure we will feel the financial effects. At the moment I’m concentrating on ways we can be of service to our faculty and students as they shift to remote teaching. Also, given our focus on art that engages the religious and spiritual, I hope to share our collection and other resources online in a way that offers comfort and inspiration to the wider community.

All of our accustomed ways of operating have been upended, but this is an opportunity to expand how we “museum.” We’ll also discern which of our improvised responses might continue once we arrive at a new normal. It’s inspiring to see the evident generosity and camaraderie as colleagues share ideas and resources, and the ways in which museums, artists, and art lovers are all coming together.

Terrence E. Dempsey, SJ, is a Jesuit priest, founding director of the Museum of Contemporary Religious Art, and the first holder of the May O’Rourke Jay Chair in Art History and Religion at Saint Louis University. He retired in 2019.

David Brinker became director of Saint Louis University’s Museum of Contemporary Religious Art in 2019. He is also an accomplished pastoral musician, flutist, and music arranger.