I SIT IN THE PEW WAITING for the service to begin. Glancing from the cross to the pulpit, I am struck by the stunning tropical flower arrangement—a contemporary design of cut bamboo, protea, aspidistra, and heliconia, rising from a circle of thorny vines. Not your typical bouquet of roses or lilies, it expresses a sensibility beyond its beauty. The open mouths of the cut bamboo call out; the spiky heliconia, both erect and hanging, speak to spent blood and powerful straining upward. It’s Sunday, January 16, 2022, and the notes in the bulletin say that the flowers are given “to the glory of God in recognition of the January 15 birthday and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” The symbolism of the arrangement is tangible. As a floral artist and longtime arranger for churches, I wonder about the vision behind this evocative design, and how other congregants connect with it as art.

Located in a grand mid-century-modern building, my congregation is National Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC. As a member of the Reformed tradition, I am aware of our iconoclastic heritage and emphasis on plain style within the worship space. My previous church home, the Old Presbyterian Meeting House in Alexandria, Virginia, was an early nineteenth-century Protestant box of bare-bone architecture. Clear glass, no paintings on the walls, no cross in the front, a few historic tombstones embedded in the floor, it honored our forebears’ distaste for distractions from the word of God. Yet, as Reformed scholar William Dyrness has pointed out (in his works Visual Faith and Reformed Theology and Visual Culture), even John Calvin, who forbade the use of images in worship, waxed eloquent on the beauty of the natural world and the presence of God in the theater of creation. Arranged flowers seem an ideal way to bring that “third book” of God into the sacred space.

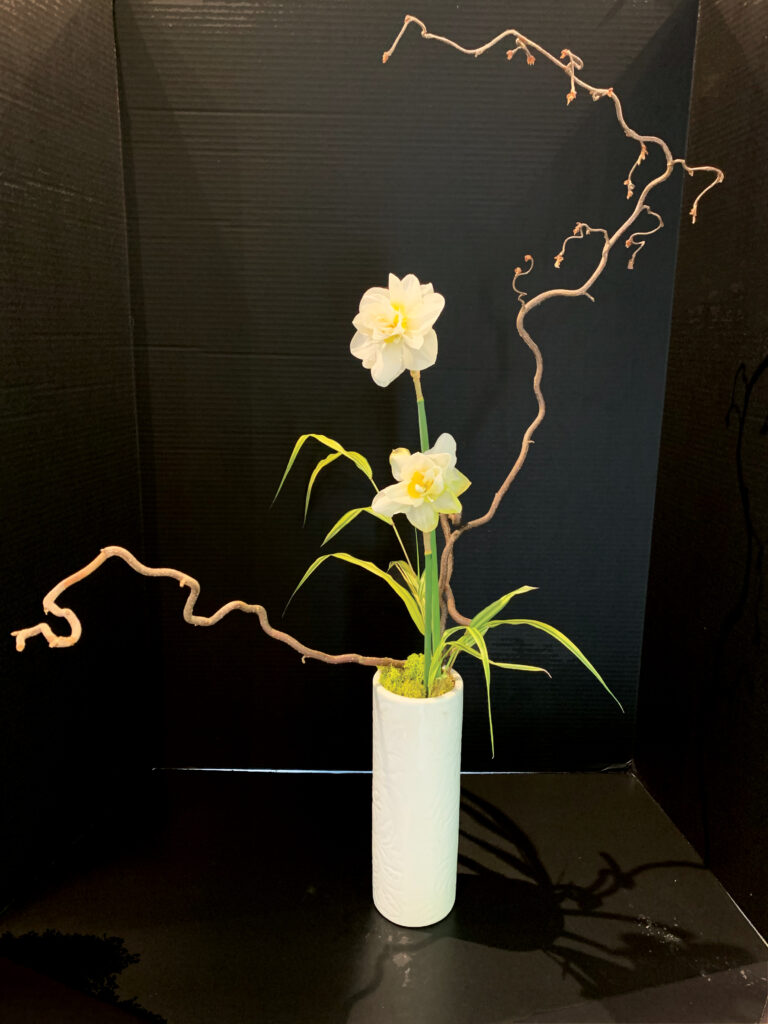

Margaret Gardner. Ikebana-style Nageire Arrangement, 2020. Reflection on spiritual discipline as “the effort to create some space in which God can act” (Henri Nouwen).

Although an important visual component of many modern sanctuaries, especially for religious holidays and significant life celebrations, floral art has barely been included in the current dialogue around art, theology, and worship. Bound by traditional aesthetics and considered primarily ornamental, floral design is seldom viewed as serious art by clergy, and too rarely considered part of the worship experience. Before women were allowed into the pulpit or church governance, flower guilds were a place in the church where they could participate and even lead. As a female contribution to worship, floral design was seen as an “appropriately feminine” effort to beautify the sanctuary. Such a marginalizing and dismissive attitude fails to recognize the creative, contemplative, and liturgical possibilities of this ancient artistic practice.

Floral designs created for religious festivals and tomb-chapels are represented in art as far back as Egyptian wall paintings from 2500 BCE. Arranged flowers were used in temples in China as early as the third century BCE. Buddhists, Taoists, and followers of Confucius placed cut plant material at altars and used flowers in religious teaching, ritual, and medicine, as did Greco-Roman priests and the early Christian church. Medieval tapestries and Renaissance painting depict the Virgin Mary within the hortus conclusus (“enclosed garden”), tying floral imagery to the allegorical reading of Song of Songs and Catholic theology. From the Egyptians through the Edwardians, flowers portrayed in art or used for seasonal designs were often selected for their religious significance or symbolic meaning, adding layers of interpretation. Whether Buddhist and Hindu carvings of lotus flowers symbolizing rebirth, or Hamlet’s Ophelia offering rosemary for remembrance, across cultures flowers have historically represented more than a gift of creation. We imbue flowers with deeper significance because we see in their utility and their beauty what Makoto Fujimura describes (in Art+Faith) as a theological touchpoint for all visual art—“the substance of things hoped for; the evidence of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1). In relation to the eternal, faith must recognize the mutability of material life. The psalmist says that our mortal days “are like the grass, they flourish like a flower of the field.” The temporary nature of floral art embraces both nature’s gifts and the transience of all creation. In its contemporary forms, it also celebrates the creativity of artistic expression.

Beverly Tam. Arrangement Honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 2022. National Presbyterian Church, Washington, DC.

Leslie Purple. Contemporary Easter Arrangement under Construction: Sun Rising on the Rood Screen, 2008. Saint Thomas’ Church, Whitemarsh, Pennsylvania.

Different eras develop floral-arrangement styles that reflect their own cultural emphases and aesthetics, but most arrangers follow core artistic principles, such as contrast, scale, proportion, and rhythm or visual movement. Whether tight Victorian tussie-mussies or asymmetrical art nouveau designs whose organic forms mirror nature, Western flower arranging participated in the evolution of the visual arts. Contemporary designers use abstract sculptural forms, reflecting modern art’s quest for expression, aiming toward something grander and more comprehensive than a gorgeous bouquet. International designers with groups like the World Association of Flower Arrangers promote artistic innovation, developing new styles such as free-form, synergistic, echo, and parallel. They also seek to reinterpret ideas, experiences, and even other art forms, as seen in curated floral art shows responding to works of art in museums. These contemporary designs often upend expectations and invite the viewer to participate in giving meaning to the creation. Within sacred spaces, an avant-garde approach to flower arranging could open worshippers to spiritual revelation.

Given the two-thousand-year history of altar flowers in the Western church, the time is ripe for a renewed sense of meaning and artistic innovation in religious floral display. Offered as a ministry to the church by designers, flower arrangements are valued by churchgoers primarily for their visual beauty. Yet, in bringing God’s creation into the sacred space, they provide an additional focal point for contemplation, inviting us to engage in wonder. Education in the methods, ideas, and inspirations behind a floral work would enhance the viewer’s appreciation. Such visual literacy could also enrich the worship experience by deepening reflection on the mystery of creation and our creative response to it.

In addition to educating congregations, designers need to push deeper in our spiritual and artistic explorations, recasting our vision and approach. Conventional church flower arranging has not followed modern artistic trends. The foreordained beauty of most Sunday morning flowers has minimal impact on the congregant. If, as Dante claims, “Beauty awakens the soul to act,” how could floral artistic expression promote Christian action, whether internal or external?

Modern interpretive floral designs, such as the one in honor of Dr. King, are already popular in secular culture. “If the church can adopt contemporary music, why not contemporary floral art?” asked Leslie Purple, a floral artist and flower guild leader at Saint Thomas’ Church, Whitemarsh, in a suburb of Philadelphia. Her contemporary designs—once even avoiding red and green at Christmas—at first met with considerable resistance from her congregation. While some of her early work shocked fellow parishioners, further education was well received, such as adding the scripture passages and interpretive intent behind floral designs to the church website during Advent. Purple also does traditional designs, including for memorial arrangements, where a donor may have particular flower requests. Purely decorative, donor-driven flower arrangements still bring comfort and hope to a congregation, particularly one that knew the deceased.

Flowers for the customary Sunday service, funeral, or wedding typically involve abundant groupings of gorgeous blossoms, and they are indeed uplifting, appealing to an affective theology. These installations are meant to create a positive emotional reaction. Yet the goals of godly worship run deeper than uplift, and floral art can play a more transformative role here. The tradition of church floral design is a platform on which to build an artistic dialogue with the worshipping congregation. Other faith traditions could assist that conversation.

In addition to modern art, a dominant influence on twentieth-century Western floral design was the sculptural and spiritually oriented work of Japanese ikebana flower arranging. Ikebana, which means “to make living flowers,” dates from seventh-century Japan. Developed from the sacred practice of arranging seasonal flowers for Buddhist temples, it is an art and a discipline that promotes self-awareness and inner peace in the practitioner and spiritual reflection in the viewer. Working with ephemeral, imperfect materials, ikebana accepts the evanescence of all things. Rather than commercially grown flowers chosen for their size and perfection, an ikebana arranger may select an oddly shaped branch, fading blossom, or insect-eaten leaf to reflect the materiality of the garden. Arranger-artists position branches and flowers in ways that seek to express the essence of the natural objects. Although contemporary ikebana explores personal expression, traditional ikebana styles symbolically acknowledge humanity’s place in relation to God and the natural world.

Ikebana uses line and space three-dimensionally, reaching toward viewers to draw us in, making the viewer, rather than a mass of beautiful flowers, the focal point of the design. Negative space is a dynamic element of the composition, constructed as an invitational arena rather than mere emptiness. Traditional massed church designs, by contrast, rarely make use of space and line; they may express rhythm through the placement of blooms, but the dense grouping of flowers leaves less room for the play of the imagination. Lines, by contrast, tell a story. As art critic Lance Esplund observes of two-dimensional art, “Line is a rich metaphor for the artist. It denotes not only boundary, edge, or contour, but is an agent for location, energy, and growth. It is literally movement and change—life itself.” In the context of floral design, the living material that forms those lines naturally and metaphorically evokes growth and energy.

Margaret Gardner. Ikebana-style Moribana Arrangement, 2021. Reflection on the book of Job.

Ikebana-style arrangements are often shaped as an asymmetrical triangle, with three major lines representing God or heaven, earth, and humanity. The whole design expresses harmony among the three, and the viewer is invited to share in the creative act of interpreting our relationship to the divine and the natural world. The God line is the tallest, often a curvy branch stretched to the heavens or bent protectively toward humanity and creation. Whether barren or full of leaves, pointing straight up or reaching out, it can express more than one story about the Creator. The human line, a transition between God and creation, is often the invitational line, which reaches out to draw the viewer in. It may be represented by blossoming flowers, sticks, pockmarked leaves, or simply a budding branch—the choice is telling. The earth line provides the foundation; here a variety of plant material may show abundance in an otherwise minimalistic arrangement. It could include grasses, mossy twigs, or fern.

The two traditional ikebana styles are the tall, upright nageire and the lower, more horizontal moribana, which is arranged in a shallow bowl with an open space for the water to create reflection, motion, and even temperature variation. Ikebana arrangements are meant to be a full sensory experience, pulling the viewer into meditation on nature and the divine. Through ikebana, viewers may discover or reimagine their orientation toward God and creation.

Mastery of ikebana in one of the traditional Japanese schools can take decades of study. Modern floral designers who have not trained with a master arrange “in the style of ikebana.” Having seen demonstrations by skilled ikebana artists but never entered a school, I practice traditional and modern styles of ikebana as a means of artistic expression and spiritual exploration. I have used ikebana to interpret the book of Job’s multiple perspectives on God, creation, and the human experience of suffering. As an artistic medium, it is well suited to exploring the beauty, complexity, and mutability of the natural world. I’ve also designed an ikebana-style class to be taught through church, in which time spent in a garden selecting branches and flowers offers opportunity for prayer and reflection on one’s relation to the divine. Bringing the plant material into a sacred space to arrange in a container extends the act of devotion, reverence, and self-reflection. The final placement of flowers may then express where one locates one’s relationship to God at that moment—close or far, broken or protected, barren or blooming.

The intimate scale of traditional ikebana complements private meditation. In Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, worshippers place arranged flowers to mediate connection with the divine. The power of this practice lies not simply in its aesthetic value, but also in its agency: by placing flowers in a temple, worshippers do something. In the West, the practices of throwing rose petals at a wedding or dropping soil on a grave offer parallels of sorts; while neither act is art, both use natural elements to connect, in joy and grief, with fellow humanity—and, for many, with the holy. Most people understand the social relevance and symbolism of these rituals without being told. They are imbued with cultural meaning and have a role in healing and community integration.

Beverly Tam. Reflection on John 15:5 (“I Am the Vine; You Are the Branches”), 2019. National Presbyterian Church, Washington, DC.

In contrast, the flower arrangement at the front of the sanctuary every week may be admired for its artistry, but without a shared language of the symbolism of flowers or awareness of the arranger’s spiritual vision, it conveys no deeper understanding of reality. It may offer traditional elements of good art—beauty, perspective, craftsmanship—but only at a rudimentary level. While churches do not need to teach the Victorian language of flowers (whose symbolism in bouquets was used to convey the unspoken feelings of male admirers), we could, in the spirit of ikebana, use the art of floral design already present in worship to engage congregants in theological and spiritual reflection. If tied to the sermon or scripture readings, the altar arrangement could be a point of contemplation for the congregation, or even a focus of the homily.

As members of a tradition that worships the mystery of the Word made flesh, Christians already celebrate the materiality of existence. Together with all humanity, we are also gifted with an intuitive response to elements of the natural world. In a vase of flowers or a sunset, we recognize the joy of creation. Within a church, artfully arranged flowers can go beyond beautification of the sanctuary to illuminate still more sacred spaces—the human heart and mind. Temporal and seasonal, flower arrangements already draw us to reflect on our impermanence in relation to God. They also respond to the scriptural call of Leviticus 23:40: “On the first day you shall take the fruit of majestic trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God for seven days.” The visual image here is one of large-scale grandeur, of the sculptural beauty of trees and branches. The religious goal was not simply to uplift the heart in praise, but also to intimate God’s presence, and to respond. In sacred spaces, innovative floral designs can generate new ways to express human connection with the divine. Building on a long tradition, church floral artists could develop a new aesthetic experience to surprise and engage “eyes that see not” (as Denise Levertov writes in her poem “What the Fig Tree Said”). Like “Christ the Poet, who spoke in images” (Levertov again) artistic design should enrich our worship of God and deepen our understanding of God’s call.

Following the service on that Martin Luther King Sunday, a group gathered at the front of the sanctuary to express their jubilation and thoughtful responses to the contemporary flower arrangement. Several African American parishioners shared their appreciation for this meaningful recognition of Dr. King. Many reflected on what its components might signify, and everyone saw a depth of symbolism. Later I learned what the artist, Beverly Tam, intended for the design. A native of Hong Kong steeped in a long tradition of floral interpretation, she wrote, “Whenever I use bamboo, I use it as a symbol to describe and honor men with integrity and character, especially Dr. Martin Luther King.” In Ancient China, bamboo’s toughness denotes resilience; its deep-rootedness, resoluteness; its straight stem, honor; its clean interior, modesty—all attributes of a “gentleman,” as bamboo is traditionally titled. In incorporating tropical flowers, Tam placed the upright heliconia to symbolize King’s passion and fire in his attempt to bring about equality for all, while the hanging heliconia shows that his vision still lingers and urges us to continue the fight. Tam typically uses king protea to represent King himself; this year the three queen protea signified his wife, Coretta Scott King, and their daughters, Yolanda and Bernice. The variety of exotic flowers and leaves represented men and women of many ethnicities. In addition, the outstretched line of lime-green cymbidium orchid invites the viewer, in Tam’s words, to consider “fresh ideas, newness, youth, and the younger generation that are to follow and keep the dream alive.”

Tam offered a reading of her arrangement different from my own, but both worked. The complexity of the art form allows for interpretations as varied as the viewers—if we recognize it as worthy of evaluation and capable of conveying mystery and truth. Approaching flower arrangements expecting meaning and possibility opens one up to fresh experiences of grace. The continual renewal of the church requires not only poetic and prophetic voices like King’s but also new artistic means of startling us from our complacency. In many sacred spaces, and in churches most Sundays, in front of our eyes blooms the transcendent mystery that may open our minds and hearts, if we would see it.

Margaret Gardner is a floral artist and educator in Washington, DC. She serves as a ministry associate at National Presbyterian Church.