Saxtons River, Vermont

Image: Could you speak a bit about how your cultural background has influenced your work?

Eric Aho: The hyphen in “Finnish-American” is the defining detail—a disconnected, detached bridge between two cultures and centuries. My mother is Boston Irish Catholic, a special world in itself. We were raised, as my father liked to emphasize, in “Finland in America.” Eventually, a Fulbright took me to actual Finland where I learned a great deal about myself and my family’s history. The landscape is, among so many other things, about self-discovery, locating oneself in space, and exploring external forces. I’d painted the winter in New England prior to living in Finland, but there, snow and ice become an autobiographical subject. Like other Finns, I have a strong sense of communion with the woods and the natural world. There’s also a hyphen of sorts between realism and abstraction.

Image: The natural landscape of New England plays a crucial role in your work. Have you found yourself looking at it in different ways over time?

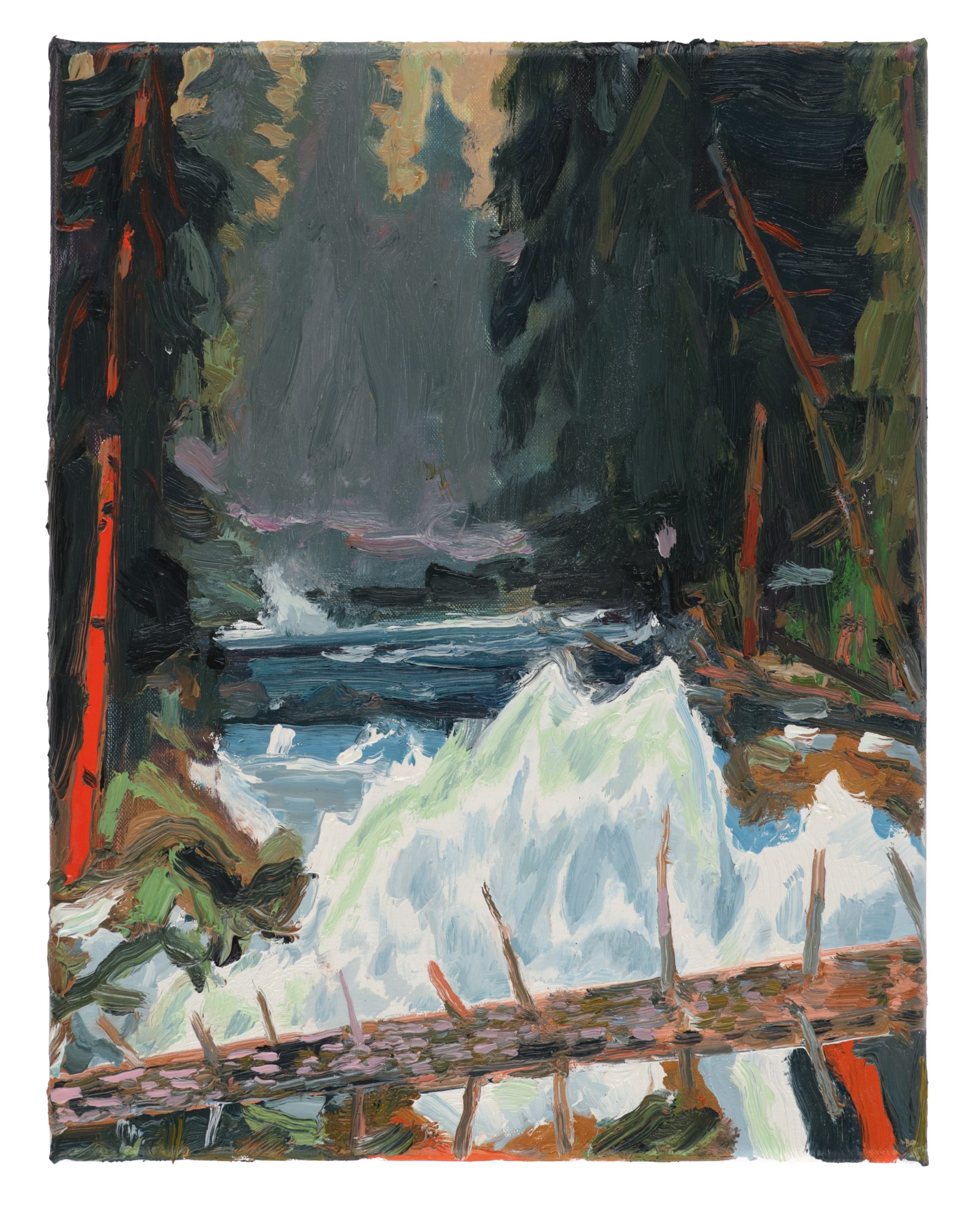

EA: The northern New England landscape is central to my painting. But I don’t think that’s what the paintings are about. Initially, I painted the landscape more empirically, loosely for sure, but rooted in close observation. After twenty years of this fact-based approach, I discovered I was looking less at the landscape itself and more at the topography evolving on the canvas—it’s like the painting became the place, like a plug was pulled from reality that existed independently.

In one of my first series from 1990, I painted along a stream deep in a hemlock ravine. I was new to Vermont and to painting. This past pandemic year I returned to a similar ravine with wild raging streams, but the interior I’m painting now is more my own and less the forest’s.

Image: What is your process like in the studio? Do you have any rituals? How do you begin a painting?

EA: I certainly have habits that have become rituals. I walk with my dog Elli to the studio following the same route. Once there, I sit and look at what happened the day before. Sometimes I listen to music (I like trying to sort out the differences between conductors handling the same piece) but mostly I prefer the quiet of the studio mixed with incidental noises of passing cars, dogs, and occasional chainsaws. At three, I stop for coffee and take another long look. Big decisions are often made looking with coffee in hand.

I try to start paintings differently each time. Sometimes I begin with a very a quick drawing in charcoal on the primed canvas. This winter, on a large canvas, I made a more elaborate drawing to start, indicating more of a plan. The resulting painting was a surprise and felt like a totally new experience. That approach isn’t habit just yet, and I don’t think it’s always wise to have a plan.

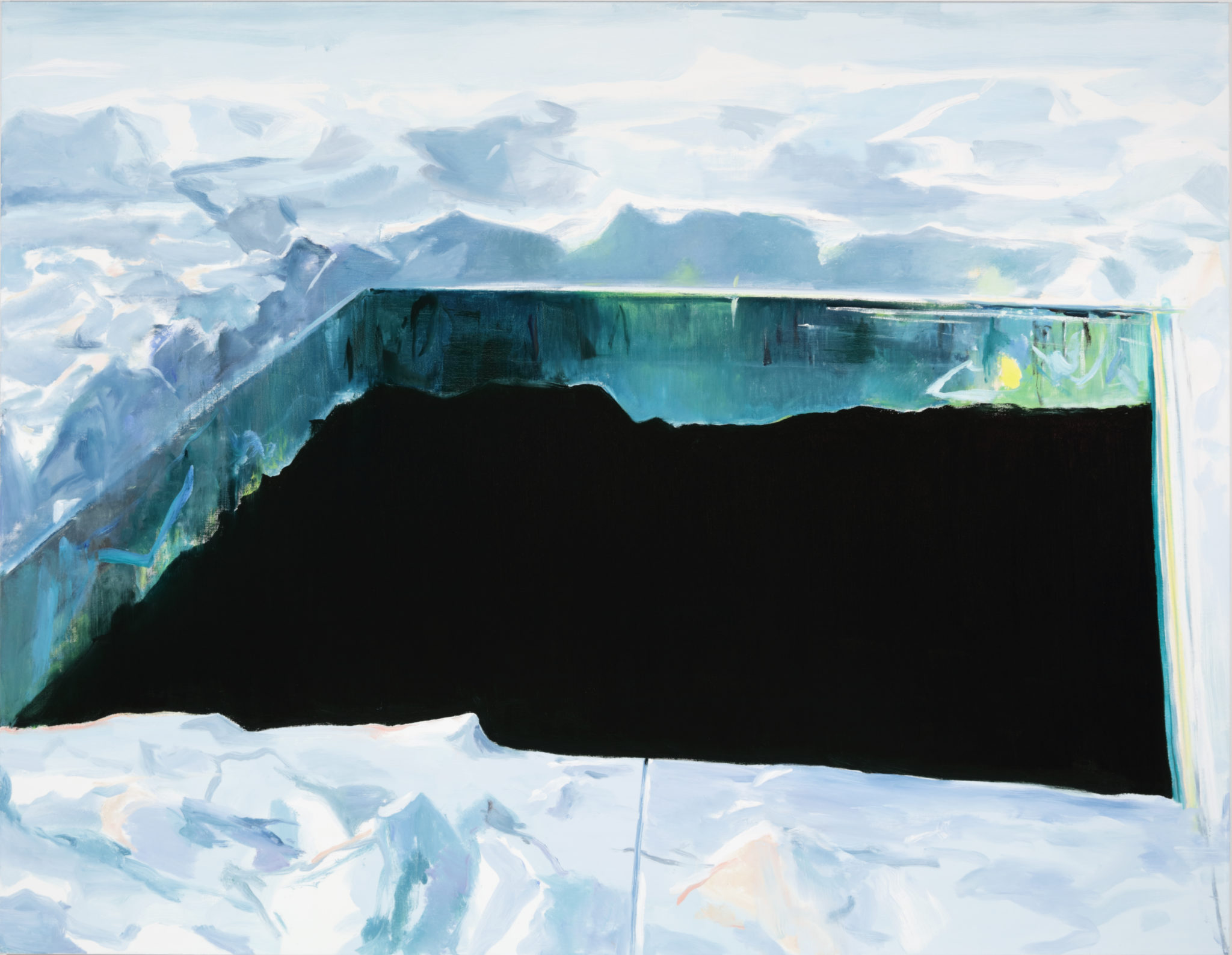

Image: What is the significance of absence, or the void, in your compositions?

EA: I cut a hole in the ice each winter, an extraordinary black trapezoid—avanto in Finnish—intended for the bracing plunge to follow the extreme heat of the Finnish sauna. The shape carries so much personal meaning. It recalls my father’s vivid stories of Depression-era ice harvests, and the chromatic black shape itself is a fundamental element of painting, a neural branch of a painter’s family tree grafting me to Gustave Courbet, Kazimir Malevich, Agnes Martin, and Ellsworth Kelly. Above all, it’s strange—a hole cut into the veneer of reality. And it’s beautiful, but full of contradictions: simple and deep; protean and manmade; darkly black and filled with color; concrete and transitory; real and symbolic. I like that the shapes oscillate between the material of the paint, the image of a hole in the ice, and then just shapes in and of themselves. These paintings allow for unexpected ways of thinking about life’s trajectory through the observation of form and color, culminating in a mysterious and inescapable vanishing point.

Image: You’ve mentioned the phrase “behind God’s back.” Where does that come from and how do you approach it in painting?

EA: There’s much poetry in the book of Isaiah where I think it has its origins. The phrase as I know it comes from the Finnish idiom “Jumalan selan takana,” which first appeared on early hand-drawn maps of the region to indicate uncharted northern outposts. To me, it refers to a world outside civilization, a place unknown, almost secret. When I’m deep in the action of painting, there’s a feeling of having stepped away from reality momentarily, into the unknown, like I’m working behind God’s back.

All images © Rachel Portesi Photography and courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Eric Aho is an American painter living in Vermont. DC Moore Gallery in New York has represented his work since 2009.