A FEW YEARS BACK, art historian and artist James Elkins published a short but pioneering book that should have crossed the radar of Image readers. On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art takes pains to claim scholarly neutrality on its subject, which is the question of why the contemporary western art world finds religious content so problematic. It will not surprise subscribers to this journal that Elkins finds most artists, critics, art historians, and curators and much of the public who follow contemporary art to be dismissive, uncomfortable, or hostile to religious subject matter, with a pronounced unease about work in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Among the test cases Elkins describes is Contemplations on the Spiritual, a 2001 multi-artist program of site-specific and site-responsive art in churches and a synagogue in Glasgow, Scotland. The author was bemused by the work of the artists, as well as by the curator’s assertion that the art spoke “eloquently in sacred spaces,” prompting visitors to reconsider how “venerable spiritual traditions touch the contemporary consciousness.” Skeptical of the project, Elkins concluded that the so-called eloquence of the work amounted to little more than a reference to religion, and the spiritual reconsideration was at best a separate outcome not necessarily connected to the experience of the work.

His conclusion comes as no surprise. In his introduction Elkins sketchily outlines the “inevitable” separation of art from religion, using ideological modernism to create his history of western art. He cites the modernist mandate as turning away from academic art and religious content as if this were historical fact, or even necessity, ignoring many examples to the contrary, as well as the current reconsideration of religion in contemporary art. (I am pleased to report, however, that Elkins, a professor at the University of Chicago, continues to engage the subject. His personal website, JamesElkins.com, lists current lecture topics including “Links between Religion and Contemporary Art,” which he describes as “a report following on from the book On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art, including material based on criticisms and new information.”)

As I was reading the book, I encountered the work of one of the participants in Contemplations on the Spiritual, Jeffrey Mongrain, at an exhibition at the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art in Sedalia, Missouri. A professor of art at Hunter College of the City University of New York, Mongrain was the subject of a poignant retrospective that traveled to five museums in the United States in 2007 and 2008. Having seen Mongrain’s work for myself, I disagree with Elkins’s characterization of religion as tangential to the encounter. In successful site-specific and site-responsive art, context can be everything.

Plate 1. Jeffrey Mongrain. Litany Rail, 2001. Clay and beads. 72 x 42 x 4 inches. Installation: Glasgow Cathedral, Scotland. Collection of the National Museum of Catholic Art, New York City.

Take, for example, Mongrain’s Litany Rail, installed in the gothic arch of the crypt of the ancient Glasgow Cathedral [see Plate 1]. (Most of the church architecture dates to the thirteenth century; the first church was built on the site around 550.) Here a sacred burial space was enhanced by the artist’s addition of a new architectural element that spoke to a religious sensibility suited to our age. More than an object of religious reference, the installation draws the viewer into religious practice.

Strings of hundreds of opalescent beads cascade from underneath the rail, down the kneeling step, and spread upon the stone floor. Their configuration corresponds to the position of a human body stooped in prayer. As we approach, Litany Rail calls on us to voice our own prayers, adding them to the countless petitions uttered in this crypt over the centuries. Mongrain’s placement of Litany Rail within the space is also reorienting. Instead of facing the interior of the crypt or the medieval burial sites, the supplicant looks upon a window open to the outdoors. The luminous upward flow of bead-prayers draws the visitor from death to light. The vertical chains also suggest the archetypal ladder linking heaven and earth that the biblical patriarch Jacob saw in his dream.

Mongrain grew up in International Falls in northern Minnesota, and says his Roman Catholic upbringing is deeply imprinted upon his life, largely through the example of his father, “a man of quiet but deep belief.” The artist describes the sort of blue-collar, Midwestern family that was the bedrock of mid-twentieth century American Catholicism. They never missed Sunday Mass, and his father’s faith was mainly evident in his love for his family, generosity to his neighbors, and respect for others. For a brief period after high school, Mongrain was a Jesuit seminarian. After leaving the seminary, his “personal politics” became more liberal, and he found himself occasionally at odds with Catholic doctrine. He nevertheless still regards himself as Catholic, primarily through living out his father’s example of goodness. Mongrain dedicated his recent retrospective exhibition and its catalog to the memory of his parents.

Mongrain spent the years 1988 to 1995 in Scotland, where he taught at the Glasgow School of Art and began making his simple, elegant, deeply resonant works. During that time he produced and installed a number of pieces at religious sites in the city, and has returned to do so even after settling in New York. While living in Europe, he traveled throughout the continent, visiting historic churches and monasteries, ruminating on his experiences and gathering ideas for his work.

Plate 2. Jeffrey Mongrain. Diviner, 2001. Clay. 54 x 19 x 19 inches. Installation: Glasgow Cathedral, Scotland. Collection of the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art, Sedalia, Missouri.

Diviner, another work from Contemplations on the Spiritual, was also installed in the Glasgow Cathedral [see Plate 2]. Measuring four and one half feet high and nearly twenty inches wide, Diviner is made of off-white, fired clay in the shape of a classically proportioned plumb-line weight. It can also be read as an abstraction of a male figure, with phallic overtones. The work exudes a restrained purity even as it dominates the space within which it is suspended. When Elkins simply writes that “Jeffrey Mongrain hung an abstract ‘stone-like figure’ outside the Lady’s Chapel,” he ignores both the symbolic nature of Diviner and its relationship to the cathedral. Elkins should know better. By contrast, David Revere McFadden, chief curator at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, who has interviewed the artist extensively and understands how site and symbol are conjoined in Mongrain’s work, offers this perceptive observation:

Mongrain takes the viewer on a journey into the world of experience and meaning on several concurrent levels. Physically and visually, Mongrain’s forms are simple, elegant and even austere, drawing upon the humble elements of the tangible world with which we are entirely familiar and comfortable. The form is revealed with grace and virtuosity. At the same time, each of these forms encases mysteries.

They do indeed. In formal terms, Diviner corresponds with the verticality of the cathedral’s evocative gothic architecture; it looks like it belongs in the space. While the work joins the artistic accretions in the long history of the church’s evolving décor, Diviner is unlike most of the historical art in the cathedral in that the haunting, hovering form does not directly illustrate religious truths or ideas—as do the stained-glass windows ringing the building, for example. Mongrain’s ceramic plumb is postmodern in its ambiguity, yet evocatively manifold in its associations. Its ecclesial context is pregnant with significant interpretive possibilities, not least God’s “plumbing” of ancient Israel as described by the Hebrew prophets. As the ultimate diviner, God sets his plumb line against his chosen people, testing their mercy, justice, and faithfulness. Did Glaswegians and tourists visiting the cathedral have a sense of being measured when they encountered Mongrain’s still, silent sentinel of judgment?

Like a number of Mongrain’s elemental forms, the plumb appears in several of his works. For Dowser, also from 2001, the artist had the same shape made from translucent glass (by his younger brother James, a glass artist). The vitreous plumb is suspended above a large, porous volcanic rock in which Mongrain has drilled a number of holes that suggest penetration by the perpendicular bob. Their unusual materials and arrangement change the significance of both the rock and plumb. The plumb, traditionally made of solid lead, an inert dead weight, becomes a vessel of light. The rock is not solid stone, but light, porous pumice, whose fiery origins give it the surprising capacity to float. The combination of light and lightness in usually weighty objects evokes a kind of miraculous transformation.

Mongrain redeployed the plumb form in Blood and Plumb (2006) where the suspended object is made of sanguine maroon-colored glass. Here it resembles a reliquary. Beneath the plumb is a sculpted pool of blood in reflective maroon Plexiglas. Its volume is equal to 1.3 gallons, the quantity that circulates in the average human male. The installation quietly insinuates the sacred in the measure of human life. If we think of the meaning of plumb as a verb—to understand something down to its depths, especially something mysterious—we can add another interpretive layer.

Plate 3. Jeffrey Mongrain. Blood Pool, 2006. Plexiglas. 47 x 88 x ¼ inches. Saint Peter’s Church, Columbia, South Carolina.

One of Mongrain’s more accessible works is Blood Pool, part of a 2006 installation in Saint Peter’s Church in Columbia, South Carolina [see Plate 3]. Here a sculpted pool of blood lies on the marble floor in front of the altar. Carved deep into the altar’s marble face is a high-relief sculpture of the Last Supper, presumably done for the church’s renovation in the early 1900s. This is a traditional liturgical work, technically accomplished and aesthetically conservative, drawn from stock Catholic iconography. Mongrain’s flat pool of wine-colored blood intervenes between the viewer and the older work, recasting the familiar tableau as a reflection in its liquid, polished surface. The mirror image is transfused with the blood/wine that Christ holds in his chalice. As with Blood and Plumb, the pool represents 1.3 gallons. Here the association is with the redeeming blood of Christ, whom the apostle Paul calls “the first man in God’s new human creation.”

Close readings of works like Litany Rail, Diviner, and Blood Pool challenge Elkins’s concern that the work in Contemplations on the Spiritual merely “references” religion. On the contrary, the specific site placement of Blood Pool enhances the existing iconography of the Eucharist at Saint Peter’s Church, taking an ecclesial décor that has turned conventionally, familiarly beautiful over time and appropriately renewing our sense of shock. The Roman Catholic celebration of the Eucharist is a refined, prescribed act. The well-worn roles and actions of the priest, altar party, and communicants have inadvertently conspired to “desanguinize” the sacrificial event at the center of the communal meal. Though Mongrain’s intentions for the piece may be multiple and layered, one effect is certain: by placing a “blood spill” at the base of the altar, he galvanizes our understanding of Jesus, not to mention the archetypal function of an altar. Blood Pool is at once tranquil, violent, and full of potential for redemption.

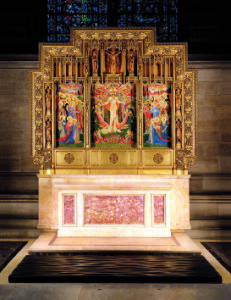

New York’s cavernous Episcopal Cathedral of Saint John the Divine has for many years been a site for contemporary artists to experiment with religious (and less than religious) expressions in music, poetry, theater, and visual art. In 2002, Mongrain was granted a project in the interior chapel called All Souls Bay. The bay contains a minimally ornamented stone altar surmounted by a traditional retable (or altarpiece) in the style of the Italian Renaissance, an elaborate gilt structure with gothic tracery framing a sculpted crucifixion group and saints. The focal point of the retable is a painted triptych showing apostles, martyrs, saints, and ecclesiastic officials adoring a triumphant, crowned Christ in kingly robes.

No small part of the challenge All Souls Bay presented to Mongrain was the retable itself. For its original congregation, at the time and place it was made, its imagery was an efficacious expression of heaven and earth. Today, the work is an anachronism. Its static, late medieval vision of the heavenly realm is no longer compelling, especially to a contemporary audience accustomed to naturalism in the arts.

Beginning in the late twentieth century, some artists felt emboldened to interact with historical liturgical art, churches, temples and synagogues by producing installations in response to these objects and sites. Of the works they have produced, a fair number are unconventional, intrusive, and imbued with irony. Intended or not, the result is often a condescension or even a dismissal of work that held considerable spiritual attraction in its own era. In many cases, the contemporary work also suffers by comparison, since it cannot compete with the technical mastery and visual abundance of the original. Moreover, its irony is an admission of its own lack of conviction. At its worst, the new work can degenerate into cynical commentary, obscuring whatever transcendent sensibility remained in the historical work.

By contrast, Mongrain’s reflective approach to historical sacred sites is compelling in its respectfulness and thoughtfully nuanced engagement. His elemental forms have an inevitability and beauty that do not clash with the art and architecture of earlier eras. Moreover, though they are not without irony, Mongrain uses it sparingly, carefully—like a cook adding saffron seasoning.

Plate 4. Jeffrey Mongrain. The Soul’s Sea, 2002. Clay, wood, and wax. 40 x 120 x 4 inches. Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, New York City.

Faced with the retable of All Souls Bay, Mongrain wisely chose not to address the richly textured historical ensemble directly. The dark, rippling ceramic rectangle that is The Soul’s Sea lies before and below the dais upon which the altar stands [see Plate 4]. Ten feet wide, it corresponds exactly to the broad dimension of the dais. The artist has modeled his black slab so as to simulate a gently flowing subterranean stream. Seen in the candlelit chapel, the fluid pattern on the reflective surface gives the mysterious illusion of moving light, perhaps alluding to the soul’s journey to radiant glory. Conceptually, Mongrain notes that the early meaning of the word soul was “that belonging to the sea.” In its monochromatic, tenebrous glimmering, I find The Soul’s Sea the perfect visual antonym, or complement, to the heavenly splendor of the retable above.

Mongrain uses the human figure infrequently, but it does appear from time to time as an element in his work, whether religious or not. In two pieces, one early and one recent, he appropriates an image of Christ, the corpus from the crucifix. As elsewhere, key to his conceptualization is the reconfiguring of the familiar to provoke new or different perceptions—and the crucifix is nothing if not Christianity’s most well worn visual cliché.

Plate 5. Jeffrey Mongrain. Tightrope, 1988-95. Stone, water, steel, and plaster. 72 x 96 x 72 inches.

Tightrope [see Plate 5] is the earlier of the two works. Mongrain has removed a small, ordinary, commercial polychrome Christ from his cross. Sundered from this support, the figure can be imagined as falling, feet down, arms up to stabilize his descent. Mongrain has reconceived the miniature crucified Jesus as walking a high wire in a shadowy environment, perhaps suggesting the forsaken solitude of Good Friday. His only aid is a parasol held aloft in his hand, much like those used by circus performers for balance. With stronger irony than usual, the artist has deployed a tacky stick-and-paper cocktail umbrella. Rather than registering as archly whimsical blasphemy (à la Andres Serrano’s notorious Piss Christ) the overall effect of Tightrope is one of pathos. That Mongrain is after something profound is indicated by the lighting, which produces a drawn out, melancholic shadow on the wall behind the installation. It reduces the viewer to silence. The title suggests the mystery of Jesus himself, a life poised between the human and the divine.

Seventeen years later, Faith once again “decrucifixes” Christ to arrive at a new perspective on an old image [Plate 6]. This time, Mongrain was not content to appropriate a preexisting figure, but modeled his own in white clay, discarding all attributes of popular Jesus imagery. There is no long hair or beard, no crown of thorns, nails, wounds, or loincloth. The facial features of this “everyman christ” express an almost ecstatic trust [see front cover]. According to Mongrain, his neoclassical androgynous male figure was inspired by both a nineteenth-century Flemish Christ sculpture and a falling character from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel. Eyes closed, the pallid figure begins his plummet to an unknown fate. He falls from a precipice of porous volcanic stone (also used in Dowser), perhaps a symbol for the lightness of being.

Throughout his work, Mongrain uses objects and forms that are elemental in their realization. Though simple, even terse, they are not to be confused with minimalist art from previous decades that sought to drain most if not all associative content. By contrast, Mongrain’s works encourage multiple and rich interpretations, and that is his intent. Leaping and falling figures loom large in the memories of New Yorkers (like the artist) traumatized by the 9/11 attacks. On a philosophical level, Faith seems to illustrate Søren Kierkegaard’s Christian existentialism, where, after all objective queries have been exhausted, the next step is the radical, subjective “leap of faith,” abandoning the self to get at the deeper truth.

Since the 1980s Mongrain’s work has covered a range of interests: religious, scientific, historical, philosophical—probing at ways these categories assist us in making sense of the world. Unlike James Elkins, who worries that Mongrain’s religious subject matter is incidental to the meaning of the works, I find Mongrain’s installations to be compelling statements of postmodern religiosity, because they are not limited to a strict Judeo-Christian framework—though they draw richly from it. So successful are they that again and again they bring greater significance to the historical sites and houses of worship in which they are placed, deepening visitors’ encounters with the sites while prompting further reflection. This happens when, like the leaping figure in Faith, we are willing to take the plunge with the artist. As Kierkegaard demonstrated, the protections of scholarly neutrality cannot take us to this level.