Sculpture is not made to function, but to make us function

—Jean-Robert Ipoustéguy (1920–2006),

__French figurative sculptor

TEN YEARS HAD passed since I last saw David Robinson, the Vancouver-based Canadian sculptor. The occasion then was a studio visit to select three works for my exhibition A Broken Beauty: Figuration, Narrative, and Transcendence in North American Art at the Laguna Art Museum. The project was intended as a reply to some twenty-five years of an irony-saturated, content-thin, craft-impoverished, and speculation-driven art world. The works in this ecumenical exhibit drew upon Judeo-Christian texts, history and art history, and North American social and cultural issues. While it garnered mixed criticism, its novelty piqued the curiosity of a wide swath of the art world and the general public, attracting numerous visitors.

So it was with A Broken Beauty on my mind that I returned to Vancouver this past summer to visit Robinson again. He still maintains his workshop in gritty Strathcona, an industrial district coursed by rail lines and full of aging warehouses and factories. To the immediate north, more tracks service the busy wharves of Vancouver Harbour. Those who follow west-coast real estate know that Vancouver is booming—its urban core bristles with high-rises in varying stages of construction. Land speculation is frenetic, and rents are soaring. Here and there among Strathcona’s warehouses, factories, wholesalers, and service industries, are signs of creeping gentrification: a gelateria, a custom wine cellar, a few microbreweries, and a bevy of Asian restaurants. Overlooking this entrepreneurial hubbub is Robinson’s Parker Street studio, in a hundred-year-old furniture factory where he rents a warren of rooms on the third floor, as well as a fourth-floor gallery for showcasing his work. To reach his multi-room facility, one rides a freight elevator, then passes through labyrinthine hallways. The grind of machinery from the cabinetmakers on the floor below reverberates throughout the building.

In describing Robinson’s workspace, I use the word studio advisedly. Yes, there can be found figures and forms in various states of completion or abandonment. But the overall sense is of a factory shop. Robinson works in the least compliant of materials—bronze and industrial steel—and on scales that most artists rarely imagine. Suspended from the ceiling are racks of lumber; leaning helter-skelter against walls are sections of plywood and sheets of gypsum. Industrial metal worktables are strewn with scraps of Corten steel, coils of wire, rasp files, glue guns, and power tools. Plaster dust, dried clay chips, and metal filings are everywhere. And we haven’t even gotten to the bronze foundry, where the pouring of molten metal and smoky fumes are routine.

I have written elsewhere about the way sculpture in bronze, stone, and carved wood—durable art—began its retreat from the contemporary art scene in the 1970s, supplanted by the less tactile modes of conceptual art, ad hoc mixed-media installations, and audio-video work. These newer modes were much less costly, and it wasn’t long before financially pressured art departments throughout North America began to scrap traditional sculpture programs. As a result, young would-be sculptors who wanted to study the craft found themselves with shrinking options. If you really wanted to mold forms out of clay, cast images in bronze, weld sections of steel, or chisel shapes from blocks of wood, you either had to find one of the few schools still offering a sculpture program, find a mentor, or learn the craft on your own. Robinson’s career has involved all three: he was awarded scholarships at schools in Toronto and Vancouver, studied under Vancouver painter, printmaker, and sculptor Joseph Caveno and ceramist Andy Blick, and forged an ethos of experimentation early on. During his formative years, he wanted to learn only as much as he needed for each sequence of sculpture. As he often recalls, “I just wanted to get to work.”

As a child he molded and carved forms out of earthen clay in his backyard; perhaps sculpture was in his genes. His parents recognized his gift and enrolled him in a fine-art academy and later secured private teachers for him. Now, at fifty-one, he brims with ideas and projects, and his studio hums with activity. Robinson relishes commissions where his sculpture will define—not merely complement—domestic, civic, and commercial landscapes and hold its own in architectural settings. A number of his works are monumental and hang suspended in the air. Smaller works combine raw industrial steel with existentially challenged, dynamic bronze figures molded or carved with anatomical authority. A handful of works subvert time-worn sculptural formats like the heroic equestrian statue, imbuing them with a forlorn and tragic sense. A subtle sense of humor is present throughout.

§

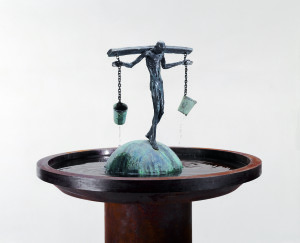

PLATE 1. David Robinson. Font, 2003. Edition of 9. Bronze, copper. 62 x 47 x 47 inches. Photo: Robinson Studio.

Back in 2005, one piece I felt was ideal for A Broken Beauty was Font [see Plate 1]. It is literally that: a functioning fountain. A pedestal supports a water basin containing a bronze hemisphere over which strides an attenuated male figure burdened with two dripping buckets. I found it iconographically unique in its tenor and daring symbolism. The idea for Font originated in 1999 when Robinson was approached by Regent College and asked to make a series of architectural pieces based upon the “I am” sayings of Jesus in the Gospel of John. The son of an Anglican priest, Robinson is somewhat guarded in speaking about his faith and has been critical of the ossifying traditionalism found in parts of the Anglican Church of Canada. In art, this traditionalism has often meant a complacency about iconography and a resistance to innovation. “When I feel the need to draw nearer to the church, I do so with a bowed head and on bended knee,” he writes. “A posture of humility, yes, but also one of cagey caution…one eye on the exits.” Wary of what control Regent might try to impose, he first recoiled at their invitation, but eventually agreed to produce a body of work to be shown in their Lookout Gallery. Font was one of them.

The artist describes Font as “an image with an overt Christian inflection.” It combines two significant aspects of Jesus: the crucified one (note the adroit use of the crossbeam that suspends the buckets) and the source of living water described in John 8. I cannot think of another recent image of Jesus that shares its novelty, functionality, and layers of meaning. Robinson later refined the work in 2003, producing an edition of nine.

Equally surprising is the tabletop piece On Holy Ground, also from 1999, further developed in 2008 as an edition of six. (It and other works not pictured here can be viewed at www.robinsonstudio.com.) Again, a single figure stands upon a smooth hemisphere of unfinished steel. Moving closer to the 12-inch figure, the viewer sees a suited, barefoot businessman holding his shoes as he raises his head to the heavens. Simultaneously witty and reverent, the work is a gentle critique of the corporate mentality, here humbled in the presence of the holy it bars from its boardrooms. One is tempted to hope that this tableau shows us where HBO’s Mad Men protagonist Don Draper—sickened by years of womanizing and ensnared in a web of lies—finally arrives. In the last frame of the series, head lifted to the sun, eyes shut, a smile playing across his face, had the rascally ad executive finally accepted grace? I’ll leave arguments about Draper’s soul to the internet, but in Robinson’s On Holy Ground, that is what appears to occur.

§

When I first encountered Robinson’s sculpture, he had been making mature work for nearly fifteen years. In 2015, as I viewed more than twenty-five years of his oeuvre, I pondered what kind of world he was creating. It would be too easy to chalk up his lone men at crossroads, his strivers grappling with impossible situations, and even his de-heroicized statuary as self-referential metaphors for his own artistic journey. He has wider interests and strategies in mind.

Any study of Robinson’s sculpture must reckon with the traditional modeling practices he uses to shape his taut and attenuated figures. His depictions of people and animals are devoid of any

PLATE 2. David Robinson. Equestrian, 1991. Edition of 6. Bronze. 32 x 9 x 32 inches. Photo: Ken Mayer.

idealizing tendencies. Neither is his imagery fixed in the cool perfectionism one associates with the late California sculptor Robert Graham. Rather, the lean physicality of Robinson’s men speaks less to any aesthetic ideal than to their preparedness for life’s difficulty. Indeed, their common anthropology is shaped by the environments in which they live, move, and have their being. His settings are spare and stark, composed of abstract geometric forms, and are distilled to monumental minimalist scenarios in which his figures doggedly contend. In To the Wall (1998), Robinson has placed a small climber on a monolithic sheet of steel [see plate opposite]. His shoulders and arms to the wall, he labors to ascend a suspended cable. If his struggle does not strike us as heroic, it is certainly real.

Robinson’s settings rarely reference the natural world. His men must find their equipoise in a manufactured realm where stability is not assured. In Solitude Standing (1993) a man wraps his arms around himself, seeming to ponder his next move, his unease underscored by the alarmingly narrow pedestal supporting him. Unlike those generals, bishops, and kings of heroic nineteenth-century monuments, exalted on massive ornamented plinths, this figure anxiously huddles over a small air grate, and we know he cannot stay there long. In the same year, the artist placed his pondering man on an imposing erector set–style industrial stairway with three landings. The figure stands at the middle level. Entitled By Any Means, the structure is suspended from the gallery ceiling away from the wall, looming over the viewer at 8½ feet high [see page 32]. The title suggests that the figure must make a move either up or down the stairs, overcoming his momentary stasis.

§

Robinson’s most difficult works are those that upend the historical iconography of sculpture. This is not a cynical ploy but rather a means to renew the tradition with a fresh treatment. As a literary analogy, think of the centuries of vigorous rabbinical dispute and affirmation of the Torah, out of which a fertile and deeply layered testimony is continually developed, even into the present (I’ve borrowed this image from Walter Brueggemann’s Theology of the Old Testament).

The equestrian sculptural tradition has been a rich source of artistic affirmation and dispute for Robinson, but not without some “killing” of the old in order to testify to something new. A wryly titled small study in bronze, Unsolicited Proposal for a Public Monument (1996), is a prime example. The viewer is shocked to discover the skeletal remains of a horse and rider lying upon a pitted metal disc, as if unearthed by archaeologists. But the grouping isn’t just meant as a joke. It has a hushed, uncanny quality, and recalls a famous passage in Ezekiel: “[The Lord] led me all around [the valley of the dry bones]; there were very many lying in the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, ‘Mortal, can these bones live?’ I answered, ‘O Lord God, you know.’” Robinson knew that there was life in the bones of equestrian sculpture and later animated a skeleton of a centaur with his Study for Interval (2000) [see page 33]. This led to the monumental Interval (2011), in which the bones took on sinew and flesh and his centaur gained a rider.

David Robinson. To the Wall, 1998. Edition of 6. Bronze, steel, string. 80 x 17 x 8 inches. Photo: Ken Mayer.

Robinson’s revisionist iconography was already evident in his earliest mature work. Three years after graduating from the Ontario College of Art in 1987, he was given his first professional exhibition at Vancouver’s Regent College and was immediately brought into the stable of the prestigious Diane Farris Gallery. The calling card that announced his arrival was a 32-inch bronze equestrian sculpture that inverted the two-thousand-year tradition of the conquering hero on horseback. Though it was modest in size, Equestrian’s monumental potential was irresistible, and Robinson scaled it up in polymer gypsum in 2009 and in bronze a year later, to measure ten feet high [see Plate 2].

In an inversion of the equestrian legacy, it is the horse that is the star of Equestrian, and it is no beast of burden. With Clydesdale-esque hooves and an alarmingly lengthened head, it brings to mind George Lucas’s AT-AT imperial walkers from The Empire Strikes Back. But if the horse is on stylistic steroids, its rider is rendered satirically, as a bald, flabby middle-aged man bound with lengths of rope—an un-hero or hapless prisoner. He can neither spur his mount nor brandish a sword; he’s just along for the ride, gaping helplessly at the sky. What a departure from those imperial Victorian and Edwardian equestrian monuments erected throughout the British Commonwealth! Of the varying horse-and-rider motifs in his oeuvre, Robinson observes that the archetype has become “thoroughly outmoded, and thus freed of its political harness. I periodically inquire after this troubled partnership of man and beast as they wander the imagination—a vivid motif in search of a better story.” Or at least a novel spin.

§

As noted earlier, a great deal of Robinson’s sculpture depicts lone nude male figures engaged in daunting labors, struggling to meet physical challenges in arduous and overwhelming settings. The artist began to consider this theme in the 1980s, during his time in Toronto at the Ontario College of Art, when he served as a teaching assistant to the sculptor George Boileau, whose work he admired. In an era of conceptualism and media art, Boileau remained fiercely committed to the human subject and emphasized the tactility of his materials. Philosophically, he had discarded the absurdism and oceanic despair of an exhausted postwar existentialism and its anguished expressionism. Attuned to his time, Boileau reckoned with what he saw as the rising culture of “corporate technologization” and its encroachment upon human values. His work is an explicit critique of this development, coolly expressed in solitary bronze figures confined in architectures he dubbed “technocratic isolation.”

Robinson was inspired by the craft and innovation of Boileau’s work—but not its message. The young sculptor had the songs of Bruce Cockburn playing on his headphones, and they sang a different tune. (For readers living south of forty-ninth parallel, Bob Dylan is the American Bruce Cockburn. See Image issues 82 and 84.) The Ottawa-born singer-songwriter, who is now seventy, has called his music “a continual reaching for God’s presence.” Among Robinson’s favorite Cockburn songs is “Civilization and Its Discontents”:

I need a miracle to keep this little thread from snapping

I know a lot about alienated man

But we’ve heard as much about that as we can stand

It’s just what happens when you let the time span

Catch you napping.

Neither napping nor standing on hoary nostrums about alienation, Robinson knew the dead horse of existential despair had been flogged long enough and wanted none of it. As a way ahead, he set about creating a sculptural narrative that demonstrated the capacity of the human subject to act, introducing dynamism into his compositions. Putting his figures to work, so to speak, also meant abandoning the man-standing-on-a-plinth legacy of western sculpture; moving figures cannot be confined to one spot. Moreover, in setting his figures in motion, he brings out the contingency of their situations. Neither the sculptor, nor his figures, nor the viewer can be certain of the outcome of their struggles. Their labors are acts of faith, undertaken in hopes that grace will lead

PLATE 5. David Robinson. Pietà, 2015. Bronze, limestone. 15 x 16¼ x 8¼ inches. Photo: Sage MacGillivray.

them home.

Key pieces from this ongoing body of work include Suspended Figure, in which a lean and muscled nude negotiates a high wire by manipulating a pulley [see front cover]. Halfway across, he can neither advance nor go back without releasing the loose end and letting the whole wire fall. For the Moment has a man in deep concentration, laboring to connect two ends of a rope that will form an isosceles triangle, creating the structural geometry that will suspend a steel arc—a metaphor for establishing order [see page 33]. The climber in Device and Desire has reached the summit of two vertical beams and is about to pull himself up and over them [see Plate 3]. Does this conquest of formidable obstacles suggest a moral victory? Anglicans will recognize in the title a phrase from the Book of Common Prayer wherein the congregation confesses its sin: “We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts.” In each of these three works, the pedestal has given way to a dynamic situation in three-dimensional space, liberating the figure from the erect and passive pose of yore, setting him at liberty for purposeful performance, in faith that Cockburn’s “little thread” won’t snap.

§

PLATE 3. David Robinson. Device and Desire (AP), 2014. Bronze, weathering steel, steel, cement. 70½ x 12 x 9½ inches. Photo: Sage MacGillivray.

Subverting the official tradition of figurative sculpture need not lead in the ironic and cynical directions that characterized much of postmodern deconstructionist

art, especially the exploitive and sensationalist tendencies of late twentieth-century artists like Jeff Koons, Charles Ray, Kiki Smith, and Damien Hirst. Robinson’s consummate mastery of and respect for materials and his belief in the inexhaustible potency of the human form led him to discover more subtle, profound, and durable imagery.

A particularly compelling body of work is his seven-piece Shrouded Plinth series from 2008 and 2009. Robinson began by completely veiling two standing figures with ultrathin, form-fitting copper sheeting. While enigmatically intriguing, the first works only foreshadowed the more compelling imagery that was to come. His breakthrough work in this series was Buttress, a kneeling figure that grips the edge of a black granite plinth while seeming to lift itself erect. Indeed, the figures from this group became more forceful as he depicted them hunched, clasping their knees, or rising with effort. Among my favorites is Nascence (2008) [see Plate 4]. Kneeling on a granite cube, a figure is undergoing a kind of birth or awakening. His effort to rise is palpable, and his shroud suggests a burial wrapping. His hands, the only parts free of the shroud, steady him. I see in Nascence a suggestion of Lazarus responding to Jesus summoning him from the tomb. But Nascence is no textual illustration; it is a moment redolent with mystery. Again, Robinson has produced innovative spiritual iconography, here implying the resurrection of the body, its release from death into the promise of new life, and the attainment of the believer’s ultimate destination—transcendent physicality.

The artist hastens to say that the Shrouded Plinth series involved very little conscious planning. Rather it was his respect for and deep awareness of the materials at hand that permitted him to see in the evolving work “energy, gesture, power—that is the thing that most needs to be kept, and that is most easily lost. My own appreciation of these Shrouded Plinth figures is of the way in which this fine film of metal can mediate and eradicate the folly of my own best intentions. Amazingly, much is revealed in all we cannot see.”

Sometimes the most humble materials can lead to the most innovative forms. Take thermoplastic adhesive, also known as hot glue, a common industrial cement marketed in solid cylinders of

PLATE 6. David Robinson. Scapegoat, 2015. Bronze, concrete. 72 x 31 x 21 inches. Photo: Sage MacGillivray.

various diameters. These are loaded into a hot glue gun, melted, and applied as a dense adhesive. Robinson encountered thermoplastic adhesive when he was working construction jobs in the 1990s to supplement his income. He noticed that the hardened leftovers could be formed into supple, fluid, and highly expressive forms, and realized he could create sculptures with them. (The hardened glue object became the basis for a sculptural mold which was then used to cast a final work in bronze.) After some years of experimentation with very small works, maquettes, and larger studies, he mastered this unorthodox material. Robinson has since explored various genres and familiar historical subjects using this process, including the Hellenistic Dying Gaul, Rodin’s Thinker, and dynamic beasts that are a nod to sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye, the great nineteenth-century animalier.

Robinson recently sculpted two noteworthy religious works from thermoplastic adhesive, then cast them in bronze: Pietà and Scapegoat. The former, mounted on a ruddy wedge of limestone, is a solemn abstraction of this subject that has existed since the later Middle Ages [see Plate 5]. When the Pietà began to be rendered naturalistically, starting in the Renaissance, artists were forced to distort the bodies of Mary and Jesus to make the composition work. Mary had to be depicted as a virtual giantess in order for the corpse of her son to lie across her lap in a way that looked naturalistically possible. Michelangelo’s Pietà perfectly illustrates how an adept artist could resolve this problem, minimizing the physical discrepancy.

By abstracting his Pietà—elongating the subject, depersonalizing the figures, and reducing them to intertwined sinewy shapes, Robinson minimizes the bodily distortions required by a more representational approach. Mary and Jesus here are woven together as an idea, and the fluid glue fuses the grieving mother with her crucified son. The work is a triumph of vision made beautiful by the utter transformation of an ordinary material.

The second work, Scapegoat, is Robinson’s tribute to the late Catholic thinker René Girard, whose theory of mimetic desire and the violence it engenders influenced literary criticism, theology, psychology, and philosophy [see Plate 6]. Girard explored the ancient idea of the scapegoat, and developed the theory that societies achieve cohesion through the violent sacrifice of an arbitrarily chosen victim or group of victims. Robinson grew up in his father’s church and loyally attended until his father retired. By the time he was seven he knew long passages of the Book of Common Prayer by heart. Like many thoughtful preachers’ kids, he wanted to make sense of Christianity on his own, and his discovery of Girard’s writings as an adult answered many of his questions. He was especially struck by Girard’s argument that God repudiated social and religious scapegoating by raising Jesus from the dead, and that the Hebrew prophets exposed the futility and hypocrisy of sacrificial scapegoating. Girard and his disciples assert that the Judeo-Christian scriptures constitute a critique of primitive religious expiation and offer a new human mimesis modeled on the life and teachings of Jesus.

David Robinson. For the Moment, 1997. Edition of 12. Bronze, steel, cable. 5 x 32 x 4 inches. Photo: Ken Mayer.

Apart from Holman Hunt’s 1854 painting depicting the sacrificial animal lost in the wilderness, forlornly bearing the sins of the community, the subject of the scapegoat is rare in art, and Robinson was free to establish a new iconographic precedent. Mounted on a six-foot plinth, his sinewy animal claims the surrounding space. It does not cower or accept its victimhood. This gnarly goat is defiant, rearing up to bleat at its would-be victimizers. Note the wonderfully insolent curl of the tongue! With Robinson’s assertive Scapegoat, the social mechanisms of victimization are overthrown by those who refuse to accept their arbitrary role.

§

After nearly three decades, Robinson knows well the changes and chances that mark the artistic vocation. On this journey, new beginnings and repetitions are to be expected. But sometimes, there are premonitions—like Robinson’s childhood desire to shape clay from the family garden into a world of people and animals. The workings of artistic calling have always eluded straightforward explanation. Early promise fails. Advantages in education don’t translate to success. Vibrant work comes from unexpected quarters. Instead of trying to make sense of it, we are better off viewing authentic artistic vocation as a gift—a spiritual blessing, though not without burdens. And such gifts ought to prompt our gratitude—a response which not only opens up a work of art to us, but also the wider world—blessing multiplied.

Artists like Robinson who have lived out their vocation through years both fat and lean caution us not to expect art to deliver a perpetual aesthetic or spiritual high. Instead, they humbly ground their practice in respect for their craft and materials, remaining ever receptive to their possibilities. As Robinson told me last summer, “When I allow the honesty of the material to come to the fore, and the emerging image takes on surprising forms, I occasionally have the good sense to remember that the work itself has better ideas than I.”