AFEW YEARS AGO, Letitia Huckaby and her artist husband, Sedrick, attended a residency in the Tuscan countryside in a weathered Medici villa with a handful of other Americans. As facilitator, my role was to make sure things were running smoothly and everybody was finding their way on their individual projects. One morning, I noticed that Letitia was not there at breakfast at the huge rough-hewn oak table. Sedrick, who was tending to their three children, told me she was up on the roof, alone, as she had been every morning. I made my way up the steep stairs to the high roof terrace, expecting to find her drawing or painting en plein air. Instead, I saw her standing underneath the ancient umbrella pines, perfectly still, eyes closed. In her hand was her mobile phone.

She opened her eyes and hit a button on her phone before saying good morning.

I asked her what she was doing.

“Recording the birds. I’m praying with them,” she said.

“What are you going to do with that?” I asked.

“I don’t know. But I’ll know when it happens,” she replied with confidence.

On our way back downstairs, she said, “Did you know science used to think female birds never sang? But now they are finding out they were wrong.”

That is the best summary I can find for Letitia Huckaby’s work and her place in contemporary American art. Just then she was fascinated by the new discovery of the female voice in nature—but for her, it was not just about the birds. It was about culture, history, family, society. In her art, Huckaby is constantly pushing herself to discover those previously unheard voices. And by her openness to those voices, which many others simply cannot hear, her art becomes a voice of its own, a song for everyone to hear.

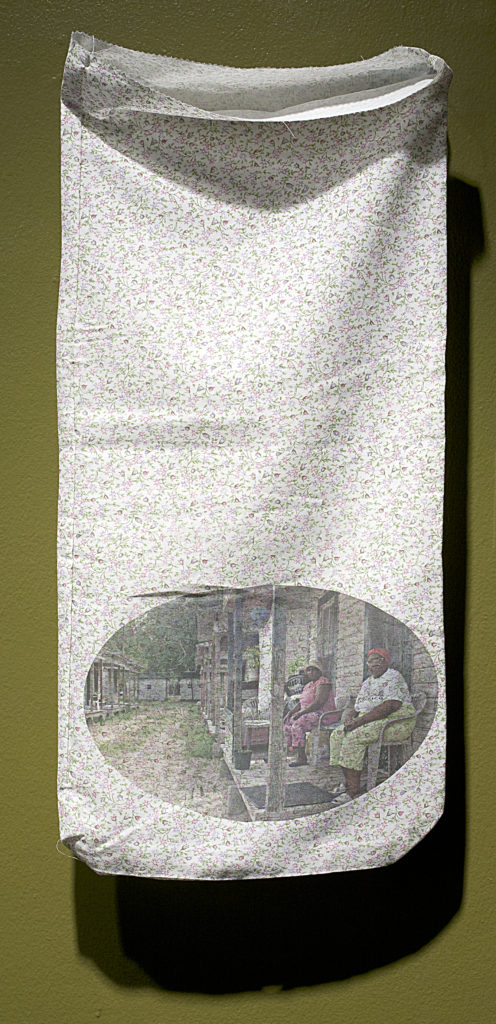

Old Slave Quarters, 2012. Pigment print on vintage flour sack. 12.5 x 26.5 inches.

Sallie (1835)

Lydia B. Kent (1864)

Lorena Spurlock (1900)

Jessie Washington (1922)

Audrey Jenkins (1946)

Letitia Huckaby (1972)

Halle Lujah (2008)

Rhema Rain (2016)

Dusty roads.

Heavy, humid heat.

Swamps and overgrowth

everywhere you look.

The moisture never quite leaves your body when you get out of the tub. You breathe in the red dirt when trucks fly by, and wait for the dust to clear as light streams through the trees above. It’s easier to walk the winding road to the store on the hill than try to pile eight or ten kids in the car—all screaming for chips and soda pop.

If I open my mouth to speak, I’m surrounded with questions of places far from here. It’s funny because I feel I’ve stepped into a history book. Slave quarters still in use, plantations now antebellum homes, and the French I worked so hard to learn in school flows like water…here.

I can’t help but think of my female ancestors and wonder what kind of life they had in the backwoods of Louisiana. What dreams did they have as they strolled down this same dusty road? —From Letitia Huckaby’s journal

The daughter of a retired army major, Huckaby was raised far from the Deep South of her ancestors. Growing up on military bases in Germany, Europe defined her world. As a child, she romanticized the backwoods of Mississippi and Louisiana as a curious wonderland she would visit from time to time. Her grandmother, aunts, and uncles were characters in a story she never fully understood.

As a young adult, she became obsessed with the cotton fields and the role that crop had played in her extended family’s life. She began photographing cotton with meditative intensity, “almost like it was a rose.”

As a photographer, she was fascinated by the lives of others, catching people in their natural conditions, documenting life in its raw, genuine beauty. She photographed jazz clubs, dance studios, streets, traveling the country trying to capture the American life that she felt was simultaneously a part of her and distant from her.

Huckaby’s speaking voice is slow. Southern. Strong. I hear her in my mind sometimes. She reminds me to listen to others. To hear their stories. Respect their voices. God made them too, she reminds me. Different is okay. Her voice is never judgmental, but a song of grace, love, and authentic friendship. It’s palpable, tangible. It’s grounded and real.

Tucked away down an old farm road on the outskirts of Fort Worth, the Huckaby home sits on several acres. Outside is the garden, from which Letitia often gathers produce for meals. Our tires crunch on the gravel driveway, alerting the family that visitors have arrived, and my husband and I are greeted with welcoming smiles before we exit the car.

Their clapboard home is humble, vernacular, oozing with hospitality that grows organically from the Huckabys’ love of family legacy and friendships. It’s comfortable without excess or kitsch. The furniture has been compiled over long years, and each piece has special meaning to Sedrick or Letitia. Pieces from her mother, his grandmother, and their aunts are mingled in a space that speaks of love above all else. Linens too are from previous generations. Dishes have fine cracks and tiny chips from years of being passed from hand to hand like offering plates at church. Mismatched wooden chairs creak to the personality of the sitter. It feels as if, before a piece of furniture can enter the cherished family space, it must gain a soul. Works from past students of both spouses are exhibited throughout the house, and Sedrick shows these off proudly, with as much or more pride as in his own work.

The home is also the seat of Letitia’s creative work. She works from their home studio while the two older children, Rising Sun (thirteen) and Halle Lujah (ten), are in school and their youngest, Rhema Rain (two), stays home. Letitia and Sedrick, who splits his time between teaching at a local university and working from their home studio, often at night, share childcare duties, and the older kids watch Rhema after school while Letitia makes dinner.

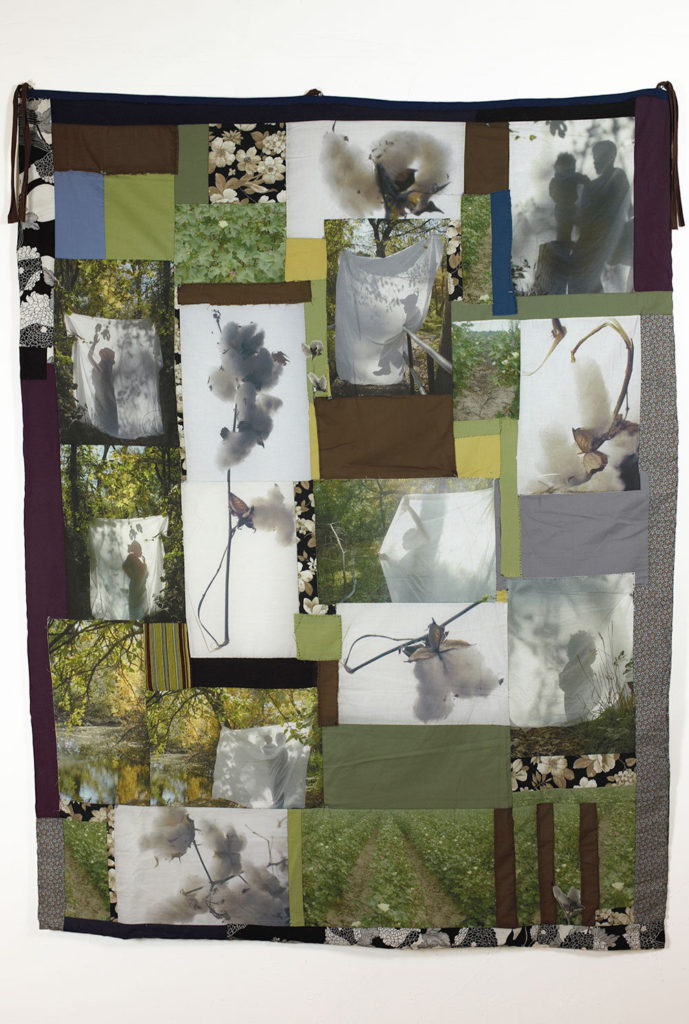

Quilt #2 (untitled), 2006. Pigment prints on fabric sewn into a patchwork quilt. 81 x 61 inches.

From this modest studio she has produced work that has garnered international attention, won awards (recently including the 2018 Hopper Prize), and been exhibited extensively in the United States and Europe. Its intimacy and simplicity seem to belie her accomplishments, but its location in the center of her home is essential: family and place are the fertile soil in which she plants and tends her art. Her body of work largely consists of multimedia stories that blend quilting and photography, threading together powerful images with textiles that pay homage to family and history.

When both spouses are artists, the work of each often influences the other. Sedrick recently began exploring the theme of family legacy through quilting and through stories of his grandmother, the matriarch of a large Fort Worth family. Through his paintings of family quilts hung in gallery-like spaces [see Image issue 90], Letitia began noticing the artistic potential of her own grandmother’s quilts. She began studying them not just as blankets passed down, but as a fine art form with powerful resonances, and she began piecing together her own quilts, learning to sew in the process. In both their work, quilts and sewing represent a tactile element of family history. Letitia’s Quilts collection involved screen-printing photographs of family members directly on cotton, treating what might be a jarring juxtaposition so gently as to make it beautiful. Letitia says she regularly asked Sedrick for input during this time, and that while she doesn’t always take his suggestions, she cherished being able to brainstorm with him.

One piece that shows their shared thematic influences, the affectionately titled East Feliciana Altarpiece, hangs over their family dining table, where it seems perfectly happy to stay, watching over the kitchen and gatherings for supper. Its multiple panels combine portraiture and lush but unsentimental landscape in a warm, tactile exploration of family history. The name comes from a Louisiana parish, part of the American southern wonderland Letitia visited as a child. The central panel is a painting of Letitia’s grandmother. Her posture of kindness, her evident contentment—for me, everything about her brings back memories of my own great-grandmother in her Arkansas farm house, sitting back on her sofa after a long day of preserving figs or shelling purple hull peas, fingernails stained a permanent violet. She is flanked by landscape images, including a mysterious white goat entering a thicket and a junkyard of cars under a lone tree in divided panels. The altarpiece is surmounted by a blazing cross of light against dark red fabric.

Under this ordinary saint’s wise and loving gaze, our two families break bread together. The Huckaby dining room becomes a chapel dedicated to hospitality, hallowed by East Feliciana Altarpiece, with the supper table as altar bringing us all together.

Following the death of her father, Huckaby turned her artistic eye inward for a time. When she began her Bayou Baroque series, she was ready to shift her focus outward again, bringing all the techniques she had honed through a period of introspection.

Sister Bertha, 2014. Pigment print on fabric. 42.5 x 31 inches.

The violet is the emblem of the Congregation. It does not lift its head in haughtiness; its leaves extend upon the ground; it seems to lend itself to being trod upon and has no thorns to protect itself against aggression.

It needs no glass enclosures to protect it from the cold for it endures the cruelest frost and most terrible heat. It grows in all climates; it is difficult for the wind to tear it up, and hurricanes do not break it because it is so lowly.

—Flower of the Sisters of the

Holy Family, New Orleans

The documentary portrait series Bayou Baroque looks at the beauty of a group of nuns residing at the motherhouse of the Roman Catholic order of the Sisters of the Holy Family in New Orleans. The order was founded in 1842, twenty years before the Civil War, and the sisters have lived since then as servants to children, the elderly, and the poor. At the time, it was illegal for an African American congregation to exist in Louisiana. Their founder, Henriette DeLille, was a free Creole woman of color who dared to break away from the plaçage system in which she had been born.

Under the plaçage system, European men entered into civil unions with women of African, Native American, and mixed descent. (The term comes from the French placer, meaning “to place with.”) These women were not legally recognized as wives, and the arrangements were known as places or “left-handed marriages.” In some cases, these relationships gave enslaved women their freedom, but for many it simply replaced one type of involuntary servitude with another.

Venerable Henriette DeLille believed that this type of indenture was wrong, and the religious community she founded allowed African American women to live lives of dignity, serving the oppressed and suffering with love. These women taught slave children when the law forbade it, cared for orphans left homeless by the pestilence of 1853, nursed the sick during the yellow fever epidemic of 1897, built schools to educate children of color, and confronted all forms of injustice and discrimination. More than 175 years later, the Sisters of the Holy Family still serve the needy, living communally as consecrated women under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

Huckaby first heard about the sisters on a flight to Louisiana and was immediately drawn to their story. For Bayou Baroque, she took beautiful portrait photos of the sisters, printed them on pieces on fabric, and quilted the portraits back together into large-scale wall hangings. The women were photographed either from the front or in silhouette against simple floral bedsheets, giving a delicate loveliness to the space around them. As Huckaby quilted, she added fabric pieces with other elements—flora, lace, printed scripture passages, images of female saints.

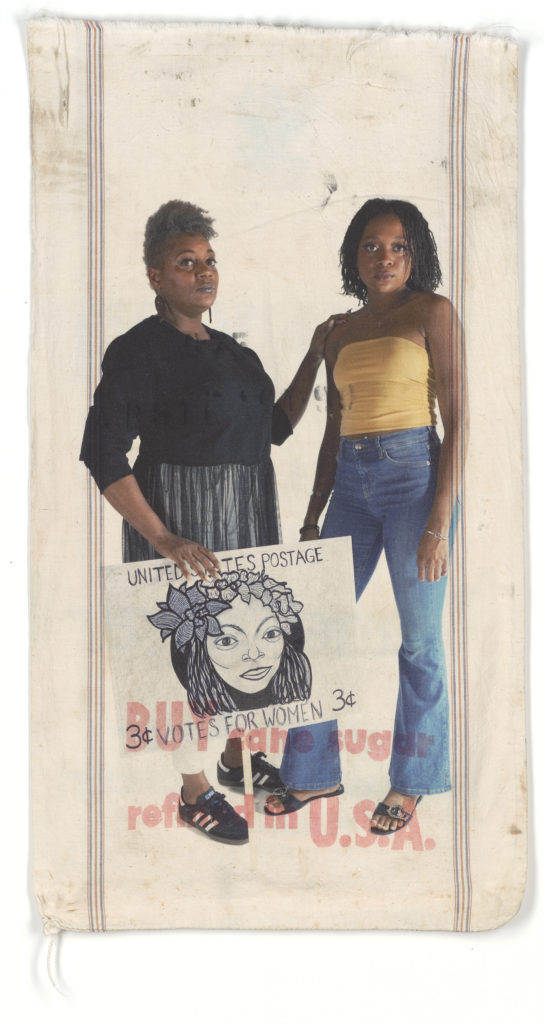

Sanah’s Three Cents, 2019. Pigment print on vintage sugar sack. 33 x 18 inches.

Each composition feels bathed with the refined elegance of an Old Master painting, giving the portraits of these humble women the same weight and balance as seventeenth-century portraits of cardinals and popes. Huckaby elevates these little-known servants of Christ to the level of history’s leading religious men, honoring their courage, sacrifice, and faith in a fresh visual vocabulary.

Over two years, Huckaby produced seven portraits of varying sizes, nine botanical prints on vintage salt sacks, and a monumental landscape. A number of the Sisters of the Holy Family made a long bus journey across town to be present at the show’s opening at PhotoNOLA 2015 in the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. Huckaby doesn’t consider the series finished, and the sisters have invited her to continue it. Until she can return to it, the Bayou Baroque portrait series travels the American South, passing through many of the areas where the sisters continue their work of lifting up the needy.

The Mercy Seat, 2012. Pigment prints on fabric. 52 x 32.5 inches.

Suffrage, Huckaby’s most recent body of work, is the one in which she most intentionally engages with contemporary political and gender issues. “Suffrage” means the right to vote, of course, but Huckaby delves deeper, looking at suffrage as a form of intercessory prayer. She has partnered with over twenty female artists of color from across the United States and Canada to create protest signs that express their personal suffrage in the form of prayers for the future. She photographs the women with their signs and prints the photos on vintage textiles—old fabrics, sugar sacks, flour sacks, and cotton-picking sacks from days gone by. The collaboration includes women like Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, a recent ArtPace resident based in Toronto and Johannesburg, and Valerie Maynard, a sculptor and printmaker born in Harlem in 1937 who is considered a matriarch of the Black art world.

The project gives voice to a vast group of female artists of color. As you look at the works, it’s a chorus you feel in the deepest part of your soul. These stitched pieces are not loud or sensationalistic, but they are graceful, honest, accessible, and impossible to ignore. They haunt to the core, dwelling in that part of the heart that knows the difference between right and wrong.

One piece from the series, Sugar and Spice, is reminiscent of Norman Rockwell’s iconic Civil Rights–era The Problem We All Live With. It depicts the Huckabys’ ten-year-old daughter holding a protest sign that reads “Enough” in spray paint [see Image issue 100]. The sign refers to a speech by Dr. Martin Luther King’s nine-year-old granddaughter, Yolanda King, at the 2018 March for Our Lives rally in Washington, DC. She said, “I have a dream that enough is enough, and that this should be a gun-free world. Period.” Sugar and Spice deliberately draws a connection between the struggles of today and those of the past, forcing us to ask how things have changed and how they’ve stayed the same.

Rhema, 2017. Pigment print on shop rag. 18 x 18 inches.

All those heirloom fabrics in Letitia Huckaby’s work—the quilting material, the sacks that would have held flour in family kitchens or been carried through cotton fields under Jim Crow—have history built into them. By pairing them with contemporary images, the artist creates a dialogue across generations about subjects that are part of the objects’ DNA.

In their graceful honesty, Huckaby’s images remind us to stay steady in our faith and in love rather than reacting in hate or anger. Like the story of Henriette DeLille and her followers, the stories she chooses to tell are the great ones that do not get enough attention. Like the female songbirds that science overlooked, Huckaby continues giving those stories voice, both the sweet and the sorrowful. Her art is an intercessory prayer offered up to overcome division, to heal brokenness, to reconcile strife, and to believe in the beauty and value of others—all others.