ARTHUR DANTO, philosopher and critic for The Nation, has characterized our period of history as “the end of art.” He doesn’t see this era as a mournful postscript on civilization, but a time in which self-conscious “fine art” as an historical progression has finally perfected itself and therefore ceased to exist as such. His theory derives from Hegel’s idea that the perfection of philosophy will be in conscious self-definition—releasing it from its own historical struggle to exist and continually define its parameters. For Danto, art and art history are the same: like the god of Joyce’s antihero Stephen Daedalus, they get refined out of existence.

Danto’s theoretical lynchpin is Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box (1964). He sees in it the final stroke of western art history—a kind of holy grail of art that self-destructs even as we grasp it and take it to our lips. The Box embodies a generation of art that draws on all the evanescence and ambiguity of late modernism, but one that holds these qualities lightly and with deadpan irony instead of the ham-fisted seriousness of the Abstract Expressionist generation.

Danto is undoubtedly right in a certain sense—and the result as he sees it is that now anything goes. No reigning style, no dominant art form, method, or agenda—high and low culture inexorably blurred. Art history ends and a new era begins in which anything is possible because nothing matters—at least not in the sense of mattering to a ruling elite or dominant cultural agenda. It’s the perfect democracy of art where anyone can be an artist and anything can be declared art. The result: a collage-like period of cultural history, an unprecedented profusion of styles and artifacts of every sort—and all of it reported and airbrushed by digital technology to remove the feel of chaos at the fraying edge. One obvious outcome has been that the art of our time is often characterized by flash, cleverness, and shock value, a momentary diversion from the feel of meaninglessness that seems inevitably to settle on a culture with no center.

Working contrary to this zeitgeist of evanescence, Jim Zingarelli painstakingly carves his images in stone—a process that has never lent itself to fashion or fad.

Stone is too cumbersome, too slow, too permanent. And unlike many of his contemporaries, Zingarelli is all about permanence. His ambition, as he has said, is to carve something that might be held and caressed in someone’s hand twenty-five hundred years from now. The one holding this fragment of his work will say with certainty, “This is something made by a human hand.” This ambition may seem modest or anachronistic given the current art world’s promise to the young and talented: fifteen minutes in the global spotlight and the potential for six-figure sales prices right out of the starting gate of Yale’s MFA program. Values like permanence and craftsmanship seem quaint in an era addicted to novelty, irony, and the temporary. But Jim Zingarelli unabashedly pursues these old-fashioned values while at the same time showing his sophistication and adeptness at a theoretical level. The key thing is that theory never outstrips performance in this artist’s work, and his ability to stay with an image through the arduous process of carving granite or marble deepens the power and mystery of his work.

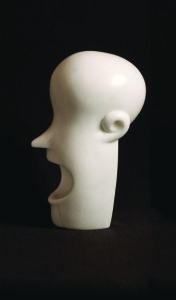

Zingarelli’s current projects include a set of twenty carved heads, Host & Hunger, that blend high and low art, echoing both the mystery of Easter Island’s colossal stone heads peering out to sea and the hilarity and goofiness of the modern comic strip. Like the late work of the New York painter Philip Guston (which attempted to refresh modern art’s ability to address existential issues by dipping into the darker imagery of the comics), Zingarelli’s tragicomic heads are compelling images of the basic human dilemma: despite our bids for immortality, we are weak and frail creatures who need to be fed. We cannot live on ideas and art alone, but require bread, water, and other humble creaturely necessities.

The world of “low” or commercial art is all about providing diversions and selling us items to meet our daily needs. Traditionally the fine arts stood above banal necessity, breathing the more refined air of philosophy and poetry. Ut pictura poesis (“As with poetry so with painting”) was the slogan. But in postmodern times, many artists and theorists have adopted a hybrid understanding of “serious” art, seeing connections to be made between high art tradition on one hand and popular imagery that speaks directly to our workaday experience on the other.

Actually the precedents for this hybrid are ancient. The Greeks practiced a high/low mixture in their drama, their household murals, and their ceramic decorations. Renaissance artists often made images that functioned as political cartoons, and Goya in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries practiced a blended approach to his art, creating cartoon-like “witch” paintings to drive home his bitter attack on the Bourbon monarchy. The nineteenth-century French painter Honoré Daumier committed a large part of his artistic output to a blended aesthetic that included allusions to the popular Cervantes novel Don Quixiote, and he became famous for his satirical lithographs in Le Journal lampooning the corrupt magistrates and clergy of Paris. Zingarelli stands in this tradition of high/low art, and has extended it into our own century by obliquely quoting ancient sculptural traditions all the while reminding us of our cultural moment, fraught as it is with the modern collision of the highbrow and the popular.

In the Host & Hunger series, Zingarelli has an even more ambitious aim—to create a lasting image that hints at a profoundly human narrative while simultaneously addressing the great aesthetic output of late modernism: minimalism, formalism, and Pop—the last frontiers of western art history. Danto’s rubric—“the end”—is predicated on the demise of the Great Man theory of culture, hence his lionizing of Warhol’s anti-heroic imagery borrowed from mass culture. But other lines of art history during the 1960s led to the work of great masters like Isamu Noguchi, the Japanese-American sculptor, and the Canadian Agnes Martin—both of whom investigated the further ramifications of that modernist perfection of form which celebrates simplicity and purity of aesthetic contemplation.

Zingarelli’s formalism is a direct heir to Noguchi and company, and yet like Guston and Warhol, he has his feet firmly planted on the ground of American pop culture. Zingarelli’s hands may be trained in the craftsmanly traditions of the Renaissance, but his imagination has been formed in the mêlée of our collage culture that effortlessly blends highbrow and low.

Yet this series of mysterious carved heads also speaks to another rising issue in the current art scene—the need to connect art and life, aesthetics and social justice. While there isn’t a trace of polemic or propaganda in Zingarelli’s work, there is nonetheless a strong sense that he is aiming at uncovering the deep connections between our hunger for images and our desire for justice and equity on the planet. Evidence of his intentions can be found in his résumé—extended service-sojourns to places like Morocco, South Africa, and Honduras, as well as community leadership to raise money for famine relief and help for the families of 9/11 victims. This said, Zingarelli never preaches in his art. Though the Host & Hunger carvings point to his steady preoccupation with the needs of the developing world, the heads never become a means to proclaim an agenda. Rather, these pieces point us to the perennial theme of need itself—basic human need. And that need includes the particular nourishment which beautiful form provides.

The contemporary art scene has no shortage of artists drawing attention to political or social causes. In fact, much of the art of the past three decades has indulged in overt, in-your-face posturing that makes a point about gender, social injustice, homelessness, environmental concerns, etc. What distinguishes Zingarelli’s work in this regard is his restraint and his ability to point the viewer back to the essential reality of our human predicament: our weakness, dependency, and the absurdity of our condition—never resorting to irony or sarcasm. This is where I believe the strong religious element lies in his work—in his acknowledgement of our creatureliness and need for nourishment. He does this with gentle humor mixed with the inescapable pathos of the Christian story.

Beyond all this, Zingarelli’s head carvings also consciously draw near to the mystery of the Eucharist and its underlying connection with the fundamental human need for both physical and spiritual nourishment. The “host” referred to in his title for the entire suite is meant to call attention both to the theme of hospitality and literally to the Eucharistic host—the bread of heaven. At one point Zingarelli even considered carving thin, wafer-like pieces of stone for a gallery visitor to “feed” the sculptured heads—their gaping mouths inviting such action. But the artist later thought better of this strategy, preferring the more suggestive absence and lack as a fitting means of communicating the multivalent meanings implicit in the Lord’s Supper and the perennial problem of starvation.

On this same theme, however, he has created a series of three hundred small sculptures called Sacramental Stones which fit into the palm of your hand—and which are periodically used in a local church liturgy, symbolizing our need to sacrifice and seek unity. The participant in worship takes a stone in the same way that one receives communion, then re-deposits it, having handled the stone while engaging in intercessory prayer. These hand-carved abstract pieces were collaboratively created by the artist and a group of his students over the course of a semester or two, further realizing Zingarelli’s desire to connect art and life, aesthetics and communal action. Aesthetic contemplation and disinterested consideration of the beautiful are simply never enough for him.

Much ink has been spilt over the problematic nature of the beautiful in a hurting world, and on its absence in the art of the past hundred years of conflicted and violent global history. Conversely, an equal amount of attention has been paid to the problem of saddling art with political, religious, or other external non-art ideas and on the need to allow the visual an equal autonomy with the musical and poetic. Zingarelli’s work is refreshing and poignant precisely because it doesn’t cave in to one or the other of these opposite and seemingly intractable issues: beauty and significance. Somehow, as it were, the artist manages to keep his head. The Host & Hunger series is part of Zingarelli’s search over the past two decades for a means to reconcile two major strands in his own work—the human figure and meditations on the beauty and significance of pure abstract form.

In three earlier bodies of work—the Stanza paintings, the Stone Table Suite, and Torsos, Zingarelli reveals a mind restless to reconcile seeming opposites. For example, in Stanza 17 the artist used a well-known Vermeer figure-and-interior painting as a color/tonality reference while at the same time self-consciously pursuing jazz-age imagery reminiscent of Stuart Davis’s colorful, zany compositions. The shapes and compositional elements in the painting dance and jiggle, jump and pop, but the color areas are sonorous, gentle, pensive, just like the Vermeer image.

Plate 12. Jim Zingarelli. Stone Table Suite, 2003. Various marbles. 61 pieces, 48 inches in diameter.

Like the Stanza paintings, Zingarelli’s Stone Table Suite has a strong jazz influence—with shapes that directly quote the Stanzas [see Plate 12]. Like the heads, this sculptural installation evokes the Eucharist. The table is situated at child height, so the viewer must sit low to the floor on the comfortable cushions which surround the sculpture. The piece has a participatory aspect—again a reference to ritual. On the table are more than a dozen small, geometric, abstract stone carvings that the participant is invited to rearrange—changing the installation repeatedly. Not surprisingly, children who visit the gallery are delighted to be not only allowed, but expected to touch and handle the art. The pieces are carefully hand-carved fragments of stone from quarries around the world—with a wide variety of colors, veining, and weight, adding to the sense that Zingarelli’s intention is to point toward global community and intellectual hospitality.

Plate 7. Jim Zingarelli. Semaphore: Granite, 2004. Granite from Barre, Vermont. 32 x 12 x 7 inches Collection: Peter Lepovsky and Diane McMillen.

Similarly, in one of the Torso pieces, Semaphore: Granite, the artist celebrates pure geometric forms reminiscent of Constantin Brancusi, while at the same time alluding to the Cycladic figurative statuary of the ancient Mediterranean [see Plate 7]. In the entire Torso series, the artist continually refines and essentializes, attempting to eliminate everything extra, anything that might distract from the underlying form—all the while striving to preserve the human presence and implicit story.

Further attempting to reconcile the polarities in his current project, in Host & Hunger: Pentellic, Zingarelli smoothes and rounds the shape of the cranium like a piece of perfectly formed fruit in one of Bernini’s bacchanals, at the same time reminding us in the overall image that his subject is a goofy, eyeless, open-mouthed man crying for food like a starving baby bird [see Plate 8]. And this is at the heart of the Host & Hunger series—preservation of the messy human story alongside the perfection and cleanliness of formalist meditations on geometry and timeless aesthetic enjoyments.

In Carrara I, Zingarelli creates stylized facial features which nevertheless feel particularized as portraits. The cavernous mouth lines gently turning and softening at the arc, the swelling of the lower lip in a characteristic pout—all these features, though repeated throughout the series, have an individualized feel.

The net effect of looking at a room filled with the heads is a feeling that one is in the presence of a large group of discrete individuals—not a faceless multitude like those depicted in Magdalena Abakanowicz’s installations [see Image issue 43]. Yet a similar intensity of investigation into the problem of facelessness is present in Zingarelli’s heads. In contrast to Abakanowicz, Zingarelli makes facelessness the occasion for receiving these pieces as highly individual—despite the seeming formula of upturned mouth, eyeless stare, and spiral ear.

In this impressive group of carvings Zingarelli has achieved a difficult balance not only between humor and pathos, but between form and story, material and process. A piece such as Zimbabwe participates in a kind of echo of the host country from which the material is mined—creating an implicit storyline both from life and from an African artistic tradition [see Plate 9]. The vertical swelling of the cranium in this piece reminds one of the wooden heads of traditional South African tribal ceremony, and the forward orientation of the face is aggressive and powerful—not plaintive and needy like some of the heads.

Other pieces such as West Rutland evince an almost angry state—and a crabby, down-turned mouth cries out for food while reviling the unjust society that leaves it hungry [see Plate 10]. By contrast, Rutland Gray gives off the feel of a gasp—the sullen shock of someone having been told, after waiting in line for hours, that the stock is exhausted [see Plate 11].

Each of these heads bears the family resemblance caused by the recognizable formal language that Zingarelli has created—and each has its own particular emotional range and personality. Color, stone or wood texture, veining, and scale all contribute to an immense and subtle range of feeling and implicit narrative. The artist has produced a set of timeless images that remain rooted in the precariousness, contingency, and absurdity of time. When seeing the entire installation of twenty heads, the viewer encounters afresh the best of modernism—its celebration of gratuitous beauty and the sensuous enjoyment of form as an end in itself. But one also sees and experiences an uncommon glimpse into the heart of the human predicament, knowing once more our own need, weakness, and dependence as a level ground upon which to see our neighbor’s need.

Plate 11. Jim Zingarelli. Host and Hunger: Rutland Gray, 2007. Gray marble from Rutland County, Vermont. 14 x 7 x 9 inches.

This last effect of the work is perhaps the most compelling—the call to neighbor-love without the slightest trace of polemic or sanctimoniousness. And this registers the hallmark of genuine art—its ability to infect us with that mysterious desire to connect with others in the human family, to see afresh our common humanity and common need—to laugh at ourselves and yet respond with action to the pressing and often tragic aspects of the world’s inequities. By walking the edge of high and low culture Zingarelli has given us a means of activating our conscience while satisfying our appetite for beauty as an end in itself.