That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation; go and learn.

—Hillel, Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Shabbat 31a

Tikkun Olam: Repairing the World, One Artist at a Time

RABBI HILLEL’S CUNNING SUMMATION of the cultural and personal practice of ethics—that charity trumps theory—leads a Jewish artist or scholar to wonder. If we can sum up the issue in one statement, one practice, then what’s the point of laboring over texts? What’s the point of following the 613 mitzvot? What is the purpose of learning Torah or Talmud?

Or, to be more specific: After thousands of years of study, argument, and commentary on religious law, after centuries of diasporic assimilation, and in light of the modernist thrust toward individual rights and freedoms, how does today’s Jewish artist reflect on the timeless role of art in Jewish life and the world at large? How does one take seriously the struggle between aesthetic and religious urges in an age of violent contest between secularism and fundamentalism?

In 1997, in the foment of local and global discourse on representations of identity, Norman Kleeblatt mounted an exhibition that exposed the general cultural anxiety in which American Jewish artists operated when questioned about their relationship to Judaism as a way of life. Entitled Too Jewish: Challenging Traditional Identities, the show played off of self-deprecating comedic references (à la Seinfeld), highlighting the religious fallout of modern assimilation. In the service of sociological query, the show presented art couched in conceptualist satire and ironic “tribal” humor. The titles alone are a dead giveaway: Workout Tallis by Neil Goldberg, Pushy/Cushy/Tushy by Rhonda Lieberman, I’m a Jew How ‘bout U? by Cary Leibowitz. Judaism, one of the key touchstones of western cosmological and moral thinking, was reduced to yet another expression of modern alienation.

The show’s exclusion of artists working outside the vein of postmodern parody was noted at the time, as was its secularist tenor. Unconsciously, Too Jewish reinforced the art world’s history of negatively profiling Jewish art as slavish cosmopolitanism, and failed to reckon with work by artists who have placed modern alienation on a larger table: those artists for whom Judaism consists of a relevant sacred way of life.

Plate 1. Ruth Weisberg. The Children, from the book The Shtetl: A Journey and a Memorial, 1970. Intaglio. 15 ½ x 12 inches.

Consider then the Los Angeles artist Ruth Weisberg, for whom contemporary Jewish religious life extends cosmic time into the real-time of human experience. Jewish life, she says, brings “a richness and balance of intellectual, emotional, and spiritual energy” to her art making. Her interest in Jewish culture as source material goes back as far as her 1971 book of etchings, The Shtetl: A Journey and a Memorial [see Plate 1]. According to a recent curatorial study by Julia R. Myers, for this project, Weisberg drew from her move to Los Angeles, the death of her maternal grandmother, and the discovery of her grandmother’s yizkor (memorial) book, which contained detailed memories of her grandmother’s birthplace—a curious nexus of events.

In light of Weisberg’s ouevre as recently surveyed by the Skirball Cultural Center, I wish to examine the ways in which the artist handles the pivotal concepts and customs that define Judaism as a way of life. Her work embodies encounters between past and present, between art history and narratives derived from the fabric of Jewish culture across time and space: family, history, the divine commandments (mitzvot), the study of Torah and Talmud (midrash), and the collective sense of tikkun olam, the divine directive to “repair the world.” To do justice to the nuance of these concepts inside the limits of an art critical essay, let me first clarify how I’ll be approaching the complex study of Jewish culture and ideas.

First, in looking at Judaism as a cultural practice, I am working from a perspective established by the artist in a recent series of phone interviews, namely, that to appreciate the aesthetic force of her work, one must recognize the tenor of her active participation in Jewish life. In comparing the study of rabbinical commentary to the broad spectrum of American spirituality, Weisberg points to the Jewish obligation to enter into hermeneutical contestation with the divine in the effort to understand the worldly purpose and meaning of Torah and Talmud. “We are G-d wrestlers,” says the artist. “We must wrestle with the challenges of everyday life.”

Second, with respect to talmudic methodology, this essay follows the practice of studying Jewish culture in a non-literal manner. That is to say, in keeping with the rigorous, centuries-old exegetical practice of midrash, the readings introduced here are presented as working definitions, subject to multiple points of view and various kinds of proofs, to be guided by engagement with the texts. Midrash, the hermeneutical study of Torah and Talmud, is necessarily an interactive learning process: between ourselves and the text, between student and student, and between the students and teacher. Also, midrashic study of Jewish texts is necessarily interdependent with the practice of mitzvot: that is, one lives out the textual commentary by observing the commandments. Rabbinical commentary offers a classic metaphor illustrating the metaphysical implications of the relationship between midrash and mitzvot, that of vessel and light: the action of performing mitzvot serves as the vessel that carries the light of midrash, the commentary that reflects the wisdom of the divine teachings.

In her approach to this tradition, Weisberg is dedicated to bringing idea and custom into deep, intimate, and necessary alignment. For her, mitzvot and midrash are an interdependent warp and woof: thinking, feeling, and doing form a generously patterned weave of community and individual life. Judaism, in other words, grounds and unites all of her efforts in a universe that encompasses intellectual, emotional, ethical, and aesthetic concerns. In the current climate, in which “being Jewish” is randomly and often hyperbolically equated with sociological and economic stereotypes, Weisberg’s passionate and critical approach to the religious literature of Judaism has never been more relevant. For the viewer, attention to Jewish thought and practice can offer a context for her contribution to contemporary art.

In Thought, Speech, and Deed: The Artist’s Mitzvot

The debate over aesthetics and ethics is an established one, whose arguments stretch across the expanse of western intellectual history from Aristotle to Alain Badiou. Within Judaism, the relationship has been subtle, shadowed by concerns for human relations and measures of freedom, and by the tension between moral judgment and moral relativism. In this context, Weisberg’s marriage of her art practice with the practice of divine commandments is striking. On the value of the ancient and continued Jewish tradition of liturgical art, she is clear: “Biblical passages define ‘handiwork’ as ‘a way to glorify G-d.’” While Weisberg has made ritual objects (such as The Open Door: A 2002 Passover Haggadah), her daring effort to merge ethics and aesthetics is rooted in her early training within the western art tradition. She grew up in Chicago, where she trained as a young art student and, as she reminisces, had the full run of the Chicago Art Institute on Saturday afternoons. Later, as an undergraduate studying in Italy, she came face to face with works by Renaissance masters like Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, and da Vinci. Her Italian period secured her fascination with chiaroscuro as a method for rendering bodies, fabric, and space. It also reinforced the Renaissance value of life drawing. Her early European education, she says, molded her visual imagination and continues to be a boundless source of artistic renewal.

Art critic and psychoanalyst Donald Kuspit has noted Weisberg’s matured rethinking of Renaissance aesthetics in his postscript to The End of Art. Launching an attack on postmodern art, he postulates the category of “New Old Masters,” including Weisberg amongst a privileged group that includes figure painters Jenny Saville, Eric Fischl, and Lucien Freud. “They are all masterful, reflective artists,” Kuspit claims:

—visionary humanists with complete mastery of their craft. For them expressive form is a way of thinking about subject matter. They know, in detail, both modern and traditional art. Like Winnicott and traditional artists, the New Old Masters believe that originality is possible only on the basis of working knowledge of the past. They are not slavish imitators of the past—they do not model their art on it, nor mechanically appropriate it in the usual postmodern way, nor does Old Master style become a mannerism in their work, however influenced by it they are—but look to it for inspiration not perfection.

If there is an ideological desire to override postmodern posturing and anesthetic scholasticism, Kuspit makes no bones about the academic terms of engagement. By introducing the question of mastery after a considerable assault on the emptiness and numbing banality of postmodern art, he means to bring art back to its intellectual, psychological, and spiritual centers.

For all its avuncular classicism, Kuspit’s affection for his New Old Masters sheds considerable light on Ruth Weisberg’s rethinking of religious genre painting from a modern Jewish woman’s point of view. Kuspit has opened a revisionist space, one that allows more careful consideration of Weisberg’s work, enriched by readings in art history, western literature, political science, and mysticism. We can now make out the intricate weave of modern Judaism embedded in the patterns of western intellectual history and culture.

Those patterns become more distinct if we read the art history to which Kuspit and Weisberg are each responding. Margaret Olin’s A Nation without Art is a good place to begin. Olin zeroes in on German art-historical framing of Jewish contributions in light of the second commandment, which prohibits the making of “graven images.” It is the second commandment after all that raises the eyebrow of Jewish and non-Jewish aesthetes alike, and according to Olin, the forefathers of art history were no exception.

In their nationalist effort to define the Greek classical roots of a true German art, early art historians struggled to assign Jewish artists to the national mix. Extrapolating from biased scholarly claims about the “anti-visual” roots of Judaism, historians including Kugler, Burckhardt, Schnaase, and Strzygowski finessed what now reads as a blatantly anti-Semitic platform, going so far as to come up with terms like “cosmopolitan imitator” or “oriental appropriator” for assimilated Jewish artists. One can only imagine how unnerved these nationalistically yearning art historians must have felt by the presence of these artists. Olin’s point in all this is to establish a basis for inspecting the intellectual discomfort twentieth-century art historians (Kenneth Clarke) and critics (Clement Greenberg) have felt regarding Jewish art (e.g. Clarke’s focus on Jewish “iconophobia”).

Anti-visual? Iconophobic? Does the second commandment, as translated from the ancient Aramaic and Hebrew, literally tell Jews to shut their eyes forever and resist the temptation to make art?

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water that is underneath the earth. Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them, for I the Lord thy G-d am a jealous G-d, visiting the iniquity of the father upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me and showing mercy unto all of them that love me and keep my commandments. (Exodus 20:4-6)

Olin, ever sensitive to Talmudic practice and historical context, starts with the excerpt from Exodus and, following rabbinical precedent, opens up the paragraph by highlighting the distinction between “making” and “worship.” She argues that to fathom the divine reasoning against the production of concrete images without recognizing the contextual, functional purpose of image-making would be to miss the psychological and metaphysical points of the teaching.

Thus, by bringing a thick read of the second commandment to bear on contemporary art practice, Olin raises another complicated modern point, namely, the adaptation of narrative imagery to address synchronic Jewish identity. Turning to Chantal Ackerman’s 1993 documentary on Eastern Europe, D’Est, which contemplates the non-idolatrous potential of gazing, Olin seizes upon Ackerman’s reference to the second commandment:

In a voiceover, Ackerman reads the text first in Hebrew [over streaming images] then in translation beginning with the second commandment…. Finally, the images fail to reappear, and Ackerman’s voice continues briefly in darkness. In the background a cello plays the Ashkenazic melody of the Kol Nidre, a legal formula chanted in synagogues at the evening service that begins the Jewish Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur.

Contemplating Ackerman’s use of Jewish liturgy as framing device, Olin sees the filmmaker rising to the test put to post-Holocaust Jewish artists, namely, to produce images that invite neither the unreflective gaze of the passive observer, nor the materialist seduction of the spectator, but provoke an active I/thou relationship between viewer and work.

In light of Olin’s reading, Weisberg is fully aware of the challenge she is taking on in trying to adhere to all Ten Commandments, much less the 613 mitzvot outlined in the Torah. Like Ackerman, she skillfully brings viewers into direct relationship with image and narrative. Her monumental installation The Scroll may be the most dramatic example in her entire body of work. Designed to mirror the structural unfolding and reading of the Torah, it encourages interactive looking and learning [see Plates 3 and 4]. Pictorial and expansive, the durational, cinematic ink drawings reconsider second commandment anxiety in light of the breadth of modern Jewish history, and of Weisberg’s own practice.

Produced over a period of three years before its first exhibition in 1987 at the Hebrew Union College, The Scroll has been called a revolutionary contribution to Jewish art. Laurence Hoffman lauds it as “a stunning reflection of Jewish modernity,” highlighting its controversial feminist content. Nancy Berman describes it as a “roomscape, a moveable modern mural, which, like the portable biblical ark, creates a sanctuary for religious expression out of an ‘any place.’”

Architectural in scale, thickly narrative in scope, The Scroll opens up over ninety-four feet of paper, layering past, present, and future to depict the grand drama of living as a Jewish woman in time and space. Viewers move along the work witnessing the interlocking cycles of the artist’s personal and collective sense of history, merging biblical with modern time. Inspired by the philosophic writings of Franz Rosenzweig, Weisberg distills her narrative into sections entitled “Creation,” “Revelation,” and “Redemption.”

In Weisberg’s oeuvre, The Scroll breaks from a predominant examination of single-frame images, allowing her to move from a snapshot approach to a cinematic, allegorical genealogy of Jewish life. The project raises fascinating technical questions about the adjustment she had to make. Weisberg says that her passionate study of Masaccio’s frescos made the shift negligible; in his works she found powerful teachers of narrative. Her long-held interest in film also helped her (an earlier long-format drawing, Children of Paradise, was based on the 1945 French film Les Enfants du Paradis), and she began to study the history of Japanese and Chinese scroll painting.

In my interviews with Weisberg, it has become clear that the American feminist movement of the 1960s and ’70s created an intellectual and artistic context for her interrogation of authoritative structures within the art community, thereby opening the door to her feminist analysis of Jewish tradition. This is evident in The Scroll, where she sidesteps the patriarchal voice that has typically narrated Jewish history, introducing a thoroughly modern one. Rather than a group of men wrapped in prayer shawls reading the Torah, Weisberg portrays herself among a close community of women—including her sister, daughter, and rabbi—each draped with a tallit, unrolling the Holy Scripture. (Women touching the Torah! Oi vey!) Conventionally speaking, the image departs in no uncertain terms from ancient, patriarchal ritual. But for those who yearn for a rethinking of Jewish life from a judicious revisionist perspective, the artist has “done a mitzvah” by showing us a lived experience of women performing the mitzvah of reading the Torah. Here the continuity, trials, and rewards of Jewish life—the events that bring us joy and sadness, the concentrated vision that helps us see past historical presumption and despair—are examined again.

To consider the artistic, philosophical, and ethical ambition of The Scroll inside the context of Jewish culture and contemporary art calls for a deeper discussion of Weisberg’s work. As she herself points out, the desire to render the complexity and rich particularity of Jewish religious ideas, rituals, and culture in a modern vernacular is wrapped up in a story of the ways Jewish artists have participated in the larger history, community, and market of modern art.

Illuminating Mitzvot: Midrash as Allegory

In the written Torah, the story of Ruth and her mother-in-law Naomi follows the Song of Songs, King Solomon’s poetical invocation of the marriage between G-d and the people of Israel. If the Song of Songs is an allegory of love and commitment, the Book of Ruth enriches the allegory by connecting it to a noble act of religious conversion. A pedagogic cornerstone of Jewish thinking on charity and loyalty, the Book of Ruth recapitulates Abraham’s step toward monotheism. The tale is full of lessons on following personal intuition, maintaining faith, and facing self-sacrifice for a future defined by the conscious decision to enter into a relationship with G-d. Ruth’s transformation from a Moabite princess to a widowed member of the Jewish people covers the breadth of the emotional and moral landscape that one navigates in taking on a Jewish neshuma, or soul.

Rather than return to her family in Moab after the death of her husband, Ruth decides to remain loyal to her mother-in-law and to the G-d of Israel. Her declaration to Naomi is often quoted: “For wherever you go, I will go. Where you stay, I will stay. Your people will be my people, and your G-d will be my G-d.” The story resonates for Weisberg in a primal manner. It is the subject of three works based on a photo of her sister Naomi and herself: a painting [see Plate 5], a drawing, and an intaglio print.

Though the artist’s psychological projection opens up fascinating territory for family systems analysis, it is the midrashic point of view—the interpretation of the ancient text—that captures Weisberg’s visual imagination. She pictures Ruth and Naomi facing each other, a sign of Ruth’s confession of loyalty. In one simple gesture, Weisberg captures the moment of conversion.

There is an oddness to the spatial relationship of the semitransparent figures, a simultaneity of the near and the far made more obvious by the dry, grassy dunes in the backdrop and the strange, upright shadows that suggest a theatrical scrim. The artist disrupts the presumed Cartesian grid in order to hint at the space of cosmic action. The formal ambiguity of the bodies suggested by delicate outlining lends an atmospheric edginess to the scene; the figures seem to materialize and dematerialize before our eyes. The metaphysics of the moment are made palpable by the carefully orchestrated values of dark and light.

Weisberg’s sensitivity to the otherworldly is firmly grounded in her study of sacred texts. Recognizing the metaphysical in life, says Weisberg, is a matter of “tuning up.” In the practice of midrash, “everything is there and you tune up. It’s like an orchestra getting ready to attend to everything.” She deliberately avoids the term “spiritual,” finding it “of no use to describe the kind of tough intellectual and psychological practice demanded of Jewish studies.” In Weisberg’s view, deep and continued study provides a “more integrated, heightened sense of life where form is more significant.” For Weisberg, form becomes significant through contemplation of divine action.

This is nowhere more evident than in her allegorical handling of the story of Jacob, Esau, Rachel, and Leah in her installation Sisters and Brothers (1994). Like The Scroll, Sisters and Brothers is architectural in size [see Plate 6]. It creates an open, tent-like structure of fourteen interlocking steel-framed, mixed-media painting panels. Four supporting panels depict the two pairs of siblings on a monumental scale (Julia Myers compares them to fourth-century BCE Greek Caryatids). In the upper panels, Weisberg focuses on gesture and emotion as she explores the aggression of sibling rivalry—in one panel two young boys fight mano-a-mano—and the emotional and moral costs of betrayal and reconciliation. Throughout, Weisberg bathes her characters in a warm, flickering incandescent amber light, using wax and charcoal to add a lively density and luminosity. Light, in Weisberg’s work, is both physical property and metaphysical allusion. She has labored over her technical handling of luminosity, and is fascinated with what she calls veils or skeins of light, and the way they can suggest more than one dimension of reality. She developed an interest in theatrical lighting during her studies with performance artist Rachel Rosenthal and was greatly influenced by a 1989 Giacometti show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art that included multiple portraits showing “inner” light. As the 2007 Skirball survey of her work showed, Weisberg “turns on” her flickering light to suggest a divinely mediated atmosphere.

If Weisberg’s Ruth and Naomi depicts a pivotal moment of religious commitment to the G-d of Israel, Sisters and Brothers depicts the old, echoing story of the breaking of that commitment. The familiar tale of Jacob and Esau is pure soap opera: fraternal twins fighting over a stolen birthright, competing sisters, a pushy mother, and true love waiting in the wings. No wonder Weisberg situates her midrash of the story in a simulated theater in the round. And while the installation’s tent shape evokes the nomadic desert life of the ancient Hebrews, its steel infrastructure hints that modernity does not free us from the consequences of birth order, personal choice, and family feud.

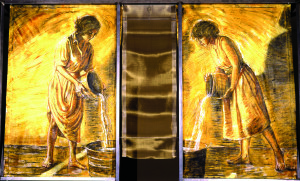

What may be most curious about Weisberg’s treatment of the scenario is her focus on Rachel and Leah. Of the four representations of the women, one large panel depicts them face to face, pouring water from earthen pots into a common basin [see Plate 7]. In conventional patriarchal readings, while the story of the two sisters lends psychological and moral weight to the drama, the main focus is on the rivalry between Jacob and Esau. Even in Weisberg’s choice of figuration, the women’s quiet actions seem innocuous and soft—but only at first glance. There is something peculiar about the light that Weisberg aims on the backs of the figures, highlighting the water in motion.

Weisberg claims that for all of its properties of light and movement and its mythopoetic allusion, water does not carry the same enigmatic, metaphysical weight in her work that flickering light does. Yet both give her the vocabulary to create a buoyant atmosphere; in her work, bodies fly, float, and waft, as if liberated from the constraints of gravity. In Sisters and Brothers, the women’s slow, careful act of pouring suggests a psychic space, as they pause to wait for the water to flow from one vessel to the other. Here, in the pause, we have the opportunity to discover existential and divine continuity.

References to women and water in Weisberg’s oeuvre stretch back to very early work including the Bath Series (1966), the painting Waterborne (1984), a series of monoprints produced circa 1996, Separating the Waters [see Plate 2], and more recently the lithograph Washing Away (1992). With its modern art-historical precedents (Cezanne, Degas) the image operates as a literary motif, helping Weisberg “visualize a space of renewal.” In the case of Sisters and Brothers, the artist reflects on an image drawn directly from her primary generative source, the Torah. The flow of the water is akin to the flow of time. The biblical female is associated with the creation of life, the continuity of family. Key to unlocking ancient codes of lineage, she is the matrix for the evolving Jewish collective and the project of redeeming the world.

Tikkun Olam Revisited: The Question of Modernity

In his near elegiac introduction to Farewell to an Idea, art historian T.J. Clark reminds us that in the modern desire for a “projected future of goods, pleasure, freedoms, forms of control over nature, or infinities of information,” we jettisoned the gods and the ancestors, those authorities that bound us to our past as a feudal, agricultural social order. Modernity defined the cultural protocol for socioeconomic and political liberation—and, with it, set up the intellectual and technocratic conditions for materialist reductionism and modern alienation: Time, once the mysterious organizing principle of the natural world, is reduced to a yardstick for the new supreme values of efficiency and speed. The universe, previously marveled at by poets and prophets, becomes the subject of systematic scientific inspection. In the modern vernacular, “cosmic” has come to mean nothing more than “wow.”

As the project of modernity has worked out its effects in the world of art, modern Jewish American artists have felt its influence in a profoundly uncomfortable way: the gods and ancestors modernity asks them to jettison are no vague spirits. Whether in self-conscious response to unconscious anti-Semitism, to the politics of intellectual cabals, or to the dissociated culture at large, Jewish artists have long felt pressure to reduce the weight of their spiritual longings so as to fit them into the thin signs of nonrepresentational abstraction, Pop irony, or conceptualist critique.

For artists like Ruth Weisberg, repression or reduction is not an option. Maybe it was the age of feminism that gave her the confidence, or the early assurance of her own vision as a young artist. Maybe it was her Italian period that let her breath in a different air, a kind that allowed her to reach back into the revered tradition of classical life drawing and find her way into the timeless traditions of Jewish literature and culture. Talking with her, one senses a personal history filled with uncanny stops and starts that eventually pushed her to dig into her own cultural and religious heritage. “I see Judaism as a constant dialogue, where there is no final absolute authority—no pope—nobody gets to say an infallible truth,” she says. “And you can change your mind. I appreciate the lack of dogma.”

One concept that might bring Weisberg into conversation with Jewish artists more alienated from the tradition than she is the teaching of tikkun olam. It’s ironic that this of all teachings could gather such a variety of artists together, hinging as it does on the second commandment. Recited daily in the traditional prayer Aleinu, a statement of religious commitment, tikkun olam is a source of rich secular and religious thinking on social justice, a reminder to the Jewish people to perform the mitzvot of “repairing the world.” With revisionist art history on one table and Talmudic texts on another, Jewish artists now have a chance at a long, hard think (with others) about what it would mean for them to repair the world. But thinking by itself, as Hillel teaches, is not enough.

For the time being, with respect to her own practice, Weisberg uses her gift as an artist to bring to light new semiotic and rhetorical ways of approaching the traditional literary practice of midrash. Works like The Scroll, she claims, represent the first attempts in Jewish art history openly and candidly to depict biblical narrative from an art-historically informed point of view. In her role as a university educator (she is dean of the Roski School of Fine Arts at the University of Southern California), she is unambiguous about the art world’s need to pay attention to Jewish culture, and the responsibility of Jewish artists to care for it. “We are in a golden age, whatever problems there are,” she claims:

We have the time to make culture, to make meaning…. We can invest more energy in Jewish culture; there is so much ambivalence towards Jewish life, which I understand, but it is time to move on, to move beyond assimilation and the former period of artistic practice where we maintained a sense of separation and privacy about Jewish identity.

As one of the first in the contemporary art community to lay her own aesthetics on the line, Weisberg articulates in thought, speech, and deed a defensible and courageous path of Jewish enlightenment. A new territory of tikkun olam has been mapped. The dark bush of modern alienation has been marked out. Future generations have now been dared to explore both the aesthetic and midrashic possibilities of growing Jewish culture. Art and history will never be the same.