Painters Bruce Herman and Makoto Fujimura, composer J.A.C. Redford, and poet Malcolm Guite have worked together on a number of projects in various combinations. We asked each of them how collaboration has changed their work and how it surprised them.

Bruce Herman

WHEN I WAS GROWING UP in the 1960s and becoming an artist in the ’70s, we all assumed originality was prime. I was warned by teachers and fellow artists against allowing my work to be influenced by others. But I have never really been convinced by the notion of being original. I’ve always hungered for artistic dialogue—not monologue—and I see it in all the artists I admire—even in famous rivalries like Matisse and Picasso’s. I’ve been more drawn to collaboration than competition.

My early attempts at this were with other visual artists. For the Florence Portfolio in 1993 (profiled by John Skillen back in Image Issue 6) I worked with Tanja Butler, Ed Knippers, Ted Prescott, Wayne Forte, Duncan Simcoe, and Christine Anderson. Those artists profoundly affected me—personally, spiritually, and artistically. Looking at my paintings you can easily see the influence of them all. I also consciously entered into dialogue with the work of Erica Grimm, Tim Lowly, Joel Sheesley, Jerome Witkin, and others who participated in our 2005 collaboration A Broken Beauty, which yielded a large exhibition and book.

More recently, my time in 2013 working on Qu4rtets with Mako Fujimura and Yale composer Christopher Theofanidis was decisive in guiding my artistic path. For that project, Mako deliberately dialed back his practice, eliminating most of the color and expressive drama of his painting, entering a minimalist space in order to allow his work to frame mine. It was a conscious act of kenosis—getting himself out of the way in order to put my work forward. Truly humbling for me. Chris Theofanidis created a thirty-five-minute piano quintet, At the Still Point, responding both to our paintings and the T.S. Eliot text that inspired the project.

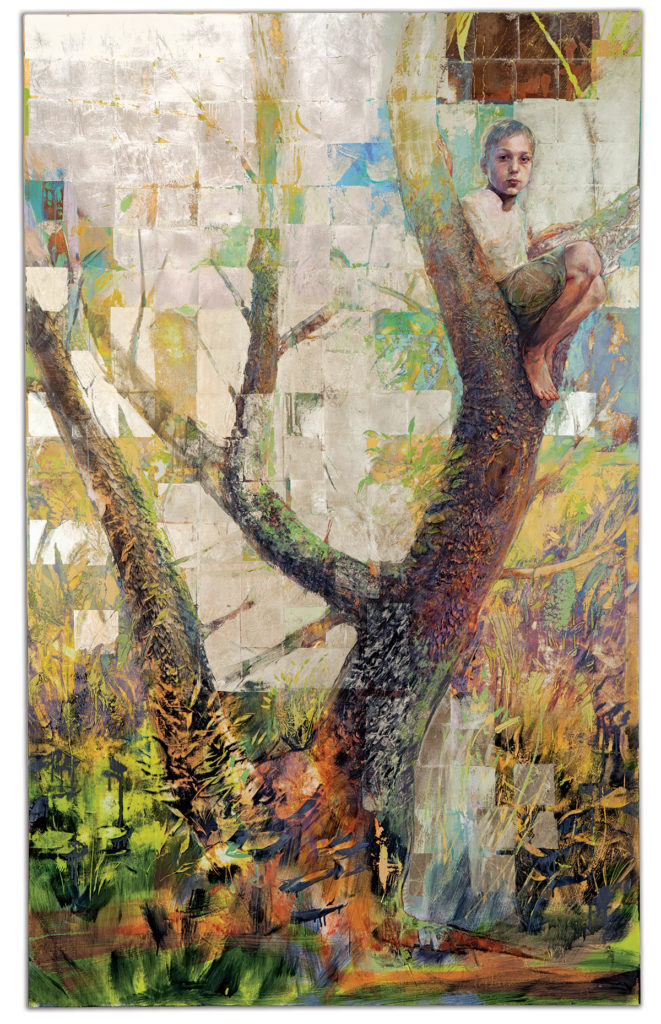

Bruce Herman. “Qu4rtets No.1 (Spring)”, 2013. Oil and gold and silver leaf on wood. 97 x 60 inches.

My own dialogue with Mako’s work had begun prior to our actual collaboration—in a series entitled The Body Broken—which incorporated the Japanese gilding techniques I learned from him. Our conversation is easily seen in those works. But in Qu4rtets there is a unique juxtaposition of my highly realized figures and implicit narrative with Mako’s minimalist, dark, non-narrative canvases. Perhaps ironically, the experience strengthened my resolve to take a maximal approach: particularized human figures, naturalistic rendering in the surrounding space, and a strong implied narrative tied to Eliot’s Four Quartets—specifically to “Burnt Norton,” “The Dry Salvages,” and “Little Gidding.” Mako tackled “East Coker,” with its darker, more somber tone.

Most recently my work has been in conversation with Malcolm Guite and J.A.C. Redford. Our collaboration Ordinary Saints has been the experience of a lifetime. When our work premiered in fall of 2018 at Laity Lodge in the Texas hill country, we saw powerful connections made in the live performance of the music, poetry recitation, and surrounding exhibition of the paintings. We discovered layer upon layer of interwoven meaning and imagery—and we saw and heard nuances of genuine communion.

I suppose that is the heart of my own desire in seeking other artists with whom to play and make art: tracking how artistic conversation eventually can grow into communion—a celebration of common ground that far surpasses our individual contributions as solo acts.

I should add that none of these projects would be possible without generous and thoughtful patrons like Walter Hansen and Kevin Chan. We also leaned heavily on theological guidance from Jeremy Begbie, who connected us with venues where the work was shown. Originality is all very well, but no art thrives without community.

Makoto Fujimura

WHEN BRUCE HERMAN AND I embarked on the Qu4rtets project in 2013 and ’14, spurred by our mutual admiration for T.S. Eliot’s masterpiece, Four Quartets, we began a journey into a surprising common discovery. It started as an attempt to lose ourselves for the sake of the other—the sake of the project, of honoring Eliot, of honoring each other. And master composer Chris Theofanidis took on the challenge with us, contributing his remarkable work.

In the studio with my assistant Lindsay Kolk, I began to conceive of a series of gesso and mineral mixes that modulated from fairly light gray tones to the darkest of blacks. We looked at the works and writings of Agnes Martin and investigated the world of Ad Reinhardt and other minimalists. As Bruce says, for me, working in a minimal gesture was a way of getting myself out of the way so that his work could be front and center. The resulting series consciously echoes Eliot’s words from “East Coker”: “O dark dark dark. / They all go into the dark. ” Quite unexpectedly, the resulting gradation of gray to black mixtures created an optical paradox: the darkest, blackest panel appeared brightest—and the lightest gray panel seemed darkest. It was particularly evident when our work was exhibited at Yale University and Roanoke College, because the lighting accentuated it. This optic phenomenon is nearly impossible to capture in a print format.

This intrigued me as Qu4rtets toured. It was exhibited and performed as far east as Hong Kong and Hiroshima, as well as in the magnificent fifteenth-century King’s College Chapel, Cambridge—the first time modern paintings were installed there. In every venue, these dark, minimal paintings highlighted Bruce’s seminal pieces and echoed Chris Theofanidis’s eloquent and timely music. Former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams inaugurated our exhibition and the musical performances at the chapel, offering deep insight into Eliot’s text and its relevance for our times.

The panels created for Qu4rtets pushed me in a direction I never expected, and for six years now I have been moving in this minimalist painterly space.

Makoto Fujimura. “Qu4rtets II (detail)”, 2012. Mineral pigments on linen. 60 x 80 inches. © Makoto Fujimura and Fujimura Institute.

Recently I have begun a new series entitled 150, a group of 48-by-48-inch paintings with base materials of a hundred-year-old sumi ink, crushed oyster shell white, with gold and silver (and possibly platinum) on Belgian linen. This new series is based on the Psalms. They are not “illuminations” like my previous series, Four Holy Gospels, but more open meditations on King David’s poetry. The materials I am using force me to work carefully and deliberately, entering into a zone that I am calling “slow painting.” Each panel is expected to take about a month to complete—so it will take over twelve years to complete all hundred and fifty.

Such an ambitious project could not have been conceived if not for the way working with Bruce and Chris on Qu4rtets taught me to get myself out of the way. King David’s words echo throughout my journey now: Yea, the darkness hideth not from thee; but the night shineth as the day: the darkness and the light are both alike to thee.

Malcolm Guite

BRUCE AND MAKO have both alluded to T.S. Eliot, and his thought is also central to my understanding of my work as a poet. A seminal text for me, and one that is very pertinent to this discussion of collaboration and change, is his early essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” In that essay Eliot argues that originality does not consist of ignoring the past or of being impervious to influence, but rather of absorbing a tradition so deeply that one is enabled to work from it and add to it with a genuine originality. Eliot wrote that the modern poet must write with an awareness:

…not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence; the historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country, has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order…. No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone.… [W]hat happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it.

Eliot’s observation that “no poet or artist of any art has his complete meaning alone” was written in 1919, before his conversion, but of course his Christian faith gives that insight an even deeper grounding: we are made in the image of a relational God and we find and exchange love and meaning in and through one another. As a poet I begin with a love of language. I recognize that language is itself a gift given to me by countless unknown others. All our words have arisen from the metaphors of forgotten poetry, and they carry with them all kinds of wisdom that it is the purpose of poetry to discover and release.

It is only the conviction that all the words I use are older and wiser than I am that allows me to write at all. This is not to say that I don’t seek to say something new. On the contrary, it is the power of an old word to generate a new meaning or reveal a new truth which keeps it alive and enriches it for the next generation. The same is true of poetic form. I make frequent use of the sonnet in both its Shakespearian and Petrarchan form, but this does not bind me into repeating the past slavishly, or condemn me to pastiche; rather it provides me with an element of discipline and concentration which intensifies the distinctive things that I have been given to say or am seeking to discover.

For me, a collaboration with other artists, such as my recent work on Ordinary Saints, with Bruce and J.A.C., is a more personal version of this longer collaboration with language itself and with form. Originality arises precisely out of a gracious response to what is already given—in this case, Bruce’s paintings and J.A.C.’s music. In one of the Ordinary Saints poems I talk about personhood itself as gift, but those lines might also be about collaboration in art:

_____ To be a person is to be a gift,

_____ Given in love. For each of us receive

_____ The gift of being from another and we lift

_____ Each other into light with every glance,

_____ Given and returned in this long dance.

J.A.C. Redford

THE COLLABORATIVE WORK of Ordinary Saints was an epic journey marked by fortunate chances, hidden hazards, unexpected revelations, narrow escapes, and, finally, an arrival where we started, grateful, as Eliot has it, to “know the place for the first time.” Like other quests, ours began with vision-casting. Bruce, Malcolm, and I poured ourselves into hours of thinking, praying, and conversation about the philosophy and theology that undergirded our endeavor. But for the journey to begin in earnest, the abstract had to become concrete, the spirit incarnate, and all of the whys give way to the hows of specific action.

In my case, that meant responding to very particular details of Bruce’s texture, color, and composition, and to Malcolm’s lines, rhythms, and rhymes, with gestures from my own discipline: melody, harmony, rhythm, and timbre. The finished work encompassed thousands of minute choices, and while some were made intuitively, most decisions were deliberate and carefully considered.

A couple of examples:

Bruce’s powerful self-portrait includes two other shadow images, a descending female form and an Italian duomo. Malcolm’s masterful poem in response to this painting weaves these two images into a story about their relationship to the artist. He chose terza rima, the form perfected by Dante in his Divine Comedy. I seized on this and mirrored the terza rima with a musical structure wherein each three-lined tercet was addressed by three measures of music in triple meter.

Once the music was laid out alongside the poem in this way, I was able to “underscore” the content of each tercet with specifically resonant music. This strategy opened up the possibility of Malcolm reciting the poem over the live music. With limited rehearsal time before the premiere, I sat in the front row during the performance and gave Malcolm subtle signals to mark the beginning of each tercet-defined measure, while Bruce displayed selected details from the painting on screens. All three of us were surprised at how beautifully the whole of this collaborative effort outstripped the parts that had gone into its creation. The sense of collaborative fruitfulness was exhilarating.

In creating music for Bruce’s portrait of theologian Jeremy Begbie, I drew heavily on my own friendship with Jeremy, as did Malcolm in his poem. Jeremy’s beautifully complex mind deserved a musical form to match it, and I settled on a fugue—but not just any fugue. Jeremy has a mischievous streak that Bruce captured in his portrait, so I decided to shake up the meter by alternating measures between 7/8 and 9/8 time. Furthermore, I had once heard Jeremy use a C-major triad as a metaphor for the Trinity, a metaphor Malcolm refers to in his sonnet. So I made sure to land on a naked C-major triad at the climax of my fugue—and sound it three times.

Specific gestures call for specific responses in a vital collaboration, but some of the resonances may not be discovered until after the artist has taken a risk—stepped out in the possibility of making a mistake and taken the first few steps in faith. It’s not an unknown condition in the Christian life:

…what we will be has not yet been made known. But we know that when he appears, we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is.

Click here to listen to excerpts from J.A.C. Redford’s Ordinary Saints cycle.