Leni Dothan is an Israeli-born artist and architect living in London. In this photo essay, based on practice-led research she undertook at the Slade School of Fine Art at University College, London, she examines and critiques how motherhood has been presented in western art history. She finds that celebrated images of obedient mothers—above all the Virgin Mary—constitute “ideological prisons” which continue to confine contemporary women. “I call these masterpieces Visual Contracts,” says the artist, “and with my work I aim to breach them and create new narratives.” In the images and captions that follow, the artist presents a powerful re-vision of motherhood.

Leni Dothan. Nordic Eve, 2017. Woman, stone, projection on boulder, digital image.

I created this site-specific work as part of my exhibition Birth & Death in Hå Gamle Prestegard, a contemporary arts venue housed in an old vicarage on the Norwegian coast. First, I took a self-portrait with a boulder in the background, then I projected this photo at night on a different boulder, just outside the gallery. Finally, I photographed the projection with a long exposure. Nordic Eve creates a new mythical narrative. This Eve was born in the North Sea. As soon as her foot touched the land, she picked up a boulder and began building. She was the first woman on earth. She had no role models, no concepts or understanding of her role. She had no need or desire for a man. She did not know about the possibility of a masculine version of herself.

Leni Dothan. Sleeping Madonna, 2011. Mother, child, pencil drawing on wall, 2:46-minute video in loop.

In this video, a young mother breastfeeds her baby until they both fall asleep. The languid act of breastfeeding gives the video the qualities of a painting. The iconic Mary becomes a real-life mother, weak and exhausted, unable to live up to her own myth. In Renaissance paintings, Mary’s traditional red dress symbolizes the future—her son’s blood and death—while a blue cloth symbolizes the church. Sleeping Madonna, made in the secular culture of Israel, is not part of the Christian religion or narrative. However, she sticks to the red dress as she is bound by a contract with the state, one in which she is asked to potentially sacrifice her son for the sake of the country.

Leni Dothan. How Much Do You, 2018. Mother, child, wooden structure, photographic image.

Mother and son stand within a wooden structure, the son on a step that makes him as tall as the mother. This step makes them equals. The middle point of this structure splits their bodies in two and covers their intimate areas. The title implies a quantitative question: How much do you love? How much do you care? How much do you want? This title has a double meaning. First, it’s the mother-son relationship that is being quantified. But the question can also be turned on the viewer. How much, we might ask, does art invite us to care or criticize?

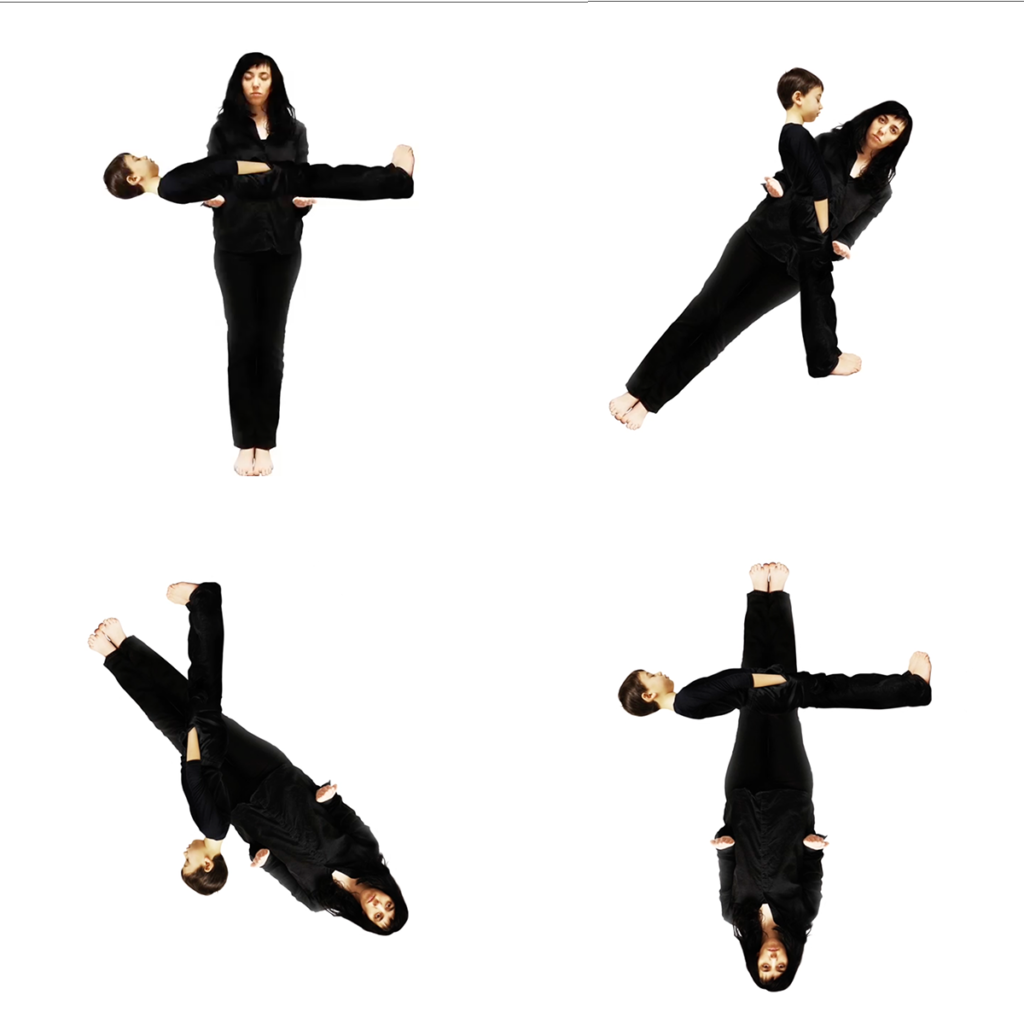

Leni Dothan. Motherchild Machine No. 7, 2019. Mother, child, wooden structure, 2:21-minute video in loop. Commissioned by Procreate Project.

Must she always be loving, caring, and ideal? Must he always be a passive victim? Can a portrait of mother and child depict a spectrum of emotions, rather than being bound to the adoration of traditional nativities? What will be the social impact if a mother is allowed to have complicated feelings toward her child, and vice versa? For this work, I created a confrontational structure that depicts mother and child as two individuals rather than an inseparable, loving unit.

Leni Dothan. Middle Ages, 2017. Mother, child, wooden structure, photographic image.

The mother in this work seems vulnerable. She is no longer the nurturing figure but now needs the support of her child. The classical roles are being redefined. Though the figures are roughly similar in proportion, the child’s maturity is visible in the way his arm covers his mother’s shoulder, a gesture of reassurance. Flesh meets flesh, meets wood. The title implies the middle point between mother and child, their average, the place in which they meet as equals. The darkness—reminiscent of Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915)—is a portal to both past and future, a suggestion of dark times which may lie ahead.

Leni Dothan. Crude Ashes, 2016.Mother, child, 3:00-minute video in loop.

This work was created as the fourteenth and final stop in the London exhibition Stations of the Cross.It explores the liminal period for Jesus and his mother when he was in the tomb. In the circular space of Temple Church, I installed a video sculpture in which a projection of mother and son silently and continually revolves in a non-space. Her palms are open, anticipating the moment of his sacrifice. As they rotate like clock hands, the two figures embody all narrative possibilities and cancel them at the same time. The sacrifice of the child is not yet determined, as it is in the traditional pietà.

Leni Dothan. Double, 2015. Wooden structure, concrete wall.

For hundreds of years, the mother has been presented as a predetermined, professional mourner. This work proposes an alternative iconography. Forged as an asymmetrical heart, the double coffin imagines a mother who chooses to die with her child, refusing to accept either his destiny or her own. The coffin appears custom made to fit a particular parent and child, and thus the structure itself becomes a replacement for the usual notation of death: dd/mm/yyyy. It stands quiet and foreboding before parents, who cannot bear the thought of sacrificing their children. Not for God, not for the state, not for anyone.

Leni Dothan is an Israeli-born artist and architect based in London. She holds a degree in architecture from the Bezalel Academy of Art & Design in Jerusalem and an MFA and PhD from the Slade School of Fine Arts at University College London.