THE PHERICHE CLINIC clings to a windswept, rocky plateau two day’s hike below Everest Base Camp. Dwarfed by the majestic Himalayan peaks that surround it, this collection of low stone buildings is the highest medical clinic in the world, offering climbers and those who live there the care and expert treatment that are essential in such an inhospitable environment. It is a place of raw, natural beauty that both literally and metaphorically takes your breath away.

It is more than fifty years since Everest was conquered, but as an ever-increasing number of people seek to stand on top of the world, Pheriche offers a salutary reminder that this is a precarious occupation. Each year there are those who do not return from its slopes, their lives lost in pursuit of a dream, their fragile human forms overwhelmed by the immense power of nature.

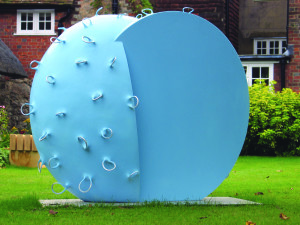

PLATE 6. Oliver Barratt. Broken Whole, 2003. Stainless steel. 6 ½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ feet.

Everest Base Camp, Pheriche, Nepal. Commissioned by the Everest Memorial Trust.

In 2000, the Everest Memorial Trust commissioned the English artist Oliver Barratt to make a memorial to Everest’s dead. The result, which was unveiled in 2003, is Broken Whole, an six-and-a-half-foot-high split cone made out of mirror polished stainless steel, which stands on a stone plinth outside the Pheriche clinic [see Plate 6]. The work’s sculptural form is simple and referential, a gentle echo of the mountains whose towering peaks dwarf those standing in the valley far below. Their distant summits and imposing mass lie beyond the controlling measure of our eyes, provoking a sense of sublime awe and terror, a shiver of wonder that courses down the spine. Yet when we gaze into the polished surface of the sculpture to see the peaks’ reflections drawn down and imprisoned between the rows of rivets that are the outward celebration of the work’s construction, they seem to take on a more human scale. We feel that we can reach out and touch them as our eyes embrace them in a single, encompassing glance.

If the exterior of the sculpture is concerned with the physical, external world, the twenty-eight-inch gap that creates the tension between the two identical halves is a more hidden, reflective space. Here, the 174 names of the dead are inscribed on the slippery walls, their letter forms dancing and waving like prayer flags in a silent act of requiem.

This is a work that defies its material solidity and strength to appear elusive and insubstantial, its surface creating a sparkling dance of ethereal light that ricochets around the valley. As we look, the solid edges of the half cones disappear, melting before our eyes into a shimmering mirage, the apparently rigid boundaries between solid and air dissolving into a haze of ambiguity. Our eyes are left to slip and slide across the mirrored surface until they reach the gap, which initially seemed to be an accident of the work’s form, but now appears solid and substantial. Gradually we come to realize that it is this void, this invariably overlooked space, that is the true focus of Barratt’s attention.

When a baby emerges from the protective intimacy of the womb, it enters into a new kind of space. In its mother there has been no sense of individuality or distinctiveness, only unity and interconnection. As soon as it is born, as it greedily gulps air into its lungs, it tastes the void. Immediately it sends out a plaintive cry, a wave of sound searching for a point of connection, a place of familiar comfort.

The space that surrounds us is a place of separation and difference. It frames us, shapes our identities, and makes inevitable the interplay of subject and object, self and other, that defines our relationships within the world. It is a vital place, yet in the act of looking our gaze streaks through this apparently empty and irrelevant expanse of air to focus on something solid, a physical object to match our physical subject. The gap itself is overlooked, passed through without consideration in our pursuit of the tangible and “real.”

For Oliver Barratt, however, the void, the gap, air, this external space, is a constant source of fascination and inspiration, a reality that he cherishes and explores, using the curves and angles of his sculptures to touch and map it, providing pools and intimate places in which it can collect and loops that frame it. Yet his forms are not just concerned with the negative space that surrounds them; they are also inspired by and seek to visualize other intangibles that shape reality. Barratt creates a visual poetry whose multi-layered resonances touch upon incorporeal essences and truths—the divine, relationships, communication, breath—sculpting poems of the void that allow us to contemplate the unseen and the unknown, to discover them as spaces of potential and presence, mystery and faith.

These invisible realities are only glimpsed, however, through their incarnation in the material stuff of this world. Barratt’s sculptures are therefore outwardly celebrations of the physical, intriguing transformations of the ordinary and everyday matter of reality. He has cast bubble wrap, plastic bags, and car mats in concrete, and has pushed fiberglass, resin, lead, and old music plates, as well as steel and wood, to their creative limits, producing works inspired by equally worldly things. As he wrote in 1992:

The Romanesque, Orthodox chants, Ethiopian biblical manuscripts, Indian temple carving, Barcelona, Barbara Hepworth, geological stratum, turnings from a metal lathe, classical Greek drapery, Django Reinhardt, Gray’s Anatomy, the Psalms, Alison Wilding, Edward Lear, and flying my kite. These are the things I think of as I work….

But rather than imitating the individualizing details of external reality, Barratt’s forms are abstract and poetic, for they seek to capture and embody the essential, emotional core of these experiences, to afford a tantalizing glimpse, a vague suggestion of the unformed essences and forms underlying reality.

Postmodern philosophers seeking to deconstruct the world may have called into question the possibility of universal, intangible truths, but in Barratt’s early works such invisible realities seem inevitable. In Friendship (1992), three rusting segments of a broken sphere lean precariously against each other in a gentle serpentine caress, their mutually dependent relationship perfectly embodying the essential form of friendship. It is an arrangement of fragmented elements in whose negative spaces and gentle curves we also catch a tantalizing glimpse of that unborn sphere that shaped its form. In a moment of transfiguration, the intangible and other are allowed to stand in this space of solid reality.

On Mount Tabor, Christ’s Transfiguration allowed Peter, James, and John to glimpse his true nature through the blaze of light that transformed his body. In Barratt’s sculptures it is not a blazing light that reveals the shadowy glimpse of other realities but the purple-gray tincture of shadow that traps and holds the void in the seams, folds, channels, pipes, and openings created by this re-assemblage of fractured forms. In these nebulous pools of space, the solidity of the real is dissolved, allowing mystery to be revealed and coexist with the physical reality of this world.

Despite its apparent emptiness, the space that surrounds us is, in fact, a place of substance, filled with sound, light, atoms, and molecules, invisible realities that find physical form on the surface of Barratt’s sculptures. More than twenty percent of the air that surrounds us consists of oxygen atoms, spinning through space until they are transformed by their encounter with other elements. The meeting of these oxygen atoms with the steel surface of works such as Splitting Shadows (1992) inevitably creates a thin film of rust that not only signals oxygen’s presence, but also suggests the less tangible processes of time and transformation that have contributed to the production of this corrosive skin. But it is not just oxygen that leaves a trace on the surface of these works. Our atmosphere is filled with dust, microscopic particles of matter that invisibly thicken the air. Inadvertently mixed into the resin of sculptures such as Belonging (1992), or accumulated on the surfaces of his works as they sit on static display, it once again becomes a skin that covers the world, a porous barrier that unsettles the boundary between void and solid.

While dust and gases give substance to space, waves of sound build an invisible acoustic bridge across the void, their sinuous curves compressing space with their presence. Although Barratt has recently played with the inclusion of sound in his work, integrating loudspeakers and music into One Voice (2006) his sculptures more usually expose its presence through their materials and forms. In many of his early works, such as Seems (1992), the presence of old music printing plates hints at the sound in the gap, their scratched and defaced notes playing a melody in our mind that seems to gently animate our encounter with the work.

Oliver Barratt. Thinking Aloud, 2005. Ceramic, aluminum wire, resin, and paint. 14 x 22 x 14 inches.

In his most recent series of sculptures and drawings—Still Moving and Stretching a Point—many of the sculptural forms themselves seem to dance through space to a silent music, the immobile solidity of earlier forms replaced by a more lyrical and fluid linearity. In works such as Between Dreaming and Flying (2004), Lines of Enquiry (2006), Open and Closed (2006) [see Plate 8], and Along these Lines (2006), thin, dancing lines emerge out of globular puddles of solid matter, to twist and pirouette through space in swooping curves that echo the forms of sound and light waves. Thinking Aloud (2005) [see back cover] and The Beginning and the End (2006) dance to a different tune, however, as slender metallic threads trace a delicate halo around more substantial forms in an elegant pas de deux that creates its own incorporeal music.

In Question and Answer (2006) the dance has stopped. Instead we seem to be confronted with a pair of headphones, a sweeping white curve terminated at each end by a funnel form that faces its twin across a narrow gap. The air between the two seems compressed by the waves of sound held in the space between. A similar funnel shape also emerges out of the sweeping dance of Opening Lines (2006), but now it faces out into the void, ready to catch any passing sound in its inquiring form.

As photons of light surf on electromagnetic waves across the void, their gravitational pull energizes the space around them. It is an unseen journey brought to an end on our retina and in our brains. The force of their impact as they enter our bodies is transformed into the kaleidoscope of color that informs our encounters with the world around. We rarely acknowledge the transfiguring properties of color, its implicit ability to reveal the invisible. But in the lustrous colors that coat the surface of Barratt’s recent sculptures such as Thoughts (2003) or Between Dreaming and Flying (2004), we can catch a tantalizing glimpse of its unseen passage as light bouncing of their reflective sky blue skins transforms their flat surfaces into a luminous whirlpool of constantly moving highlights and shadows.

On a winter’s morning, as the passage of our warm breath condenses in the cold air, a visible cloud reveals the meeting point of inner and outer, subject and object. In the mid 1990s, Barratt began a series of works that sought to give form to breath. He wanted to express the moment of a child’s first breath, to capture the cloud of frosted air on a cold morning, and to explore the normally imperceptible motion of the lungs as they expand and contract with each breath we take. The result was a series of sculptures that offer a dynamic and poetic meditation upon what it is to be alive, what it is to breathe, what it is to be inspired.

To create Breathing (1995) and Box Breath (1999) Barratt poured cast concrete into a bubble-wrap bag, producing a fossilized breath that despite its evident solidity seems pregnant with potential, its swelling form pushing out invisible ripples into the air that surrounds it. These tangible breaths emerge from the schematic lung of a simple metal frame, whose angular, mechanical forms create a striking contrast with the softer, curvaceous concrete. In Breathing the bag is full, bulging with a volume of air that the concrete seems barely able to contain. Box Breath, however, captures a more transitional moment in the process. Neither full, nor empty, it reminds us that breath is a movement, a process that drives our passage through time.

Box Bottle Breath (1995) is another work that unites a curvaceous, torso-like form of cast concrete with a rectangular steel box. They face each other across a small gap bridged by a metal bar. Despite their disparity of form and material, they are united by the space that separates them. But this is not a passive space, for as the metal box leans forward an invisible force seems to reach out from the swollen concrete bag to gently push an echo of its curving form into its unyielding metal. We find the same invisible hand at work in Holding my Breath, Breathing Space [see Plate 7], and Jacob’s Pillow (all from 1995); their solid surfaces marked by gentle indentations and lines; the residual echo of a passing, unseen presence.

For many viewers, abstraction can be a void that separates them from a work of art. It seems to speak an individual, private language unknown to the uninitiated. On the surface Barratt’s works appear abstract, unrelated to the world around. But as we have seen, these are poetic, pure forms untainted by the specifics of particular subjects and iconography that can often require interpretation. They are inspired by the common language of the world’s essential matter: dust, sound, light, space, atoms, smooth and rough, curve and angle, matte and gloss. These sculptures offer a poetry of form and surface that engages directly with our bodies and emotions rather than through the filter of subject and memory.

In recent years postmodern philosophers have questioned the validity and possibility of meta-narratives, those overarching stories that form a common framework for human experience. Writers such as Lyotard and Derrida have championed our individuality, celebrating the void as a space of difference that cannot be bridged. The Stations of the Cross are one such meta-narrative, a series of events that our human condition prevents us from ever truly accessing. We cannot know what it is to be crucified, or to carry a cross, and so we stand as perpetual spectators excluded from participation. Over the last seventeen years, however, Barratt has made three sets of Stations of the Cross whose abstract language challenges this postmodern position. Each set is different, reflecting the particular concerns and forms that were current in Barratt’s work at the time. But each is shaped by the materials and matter of the void, a natural and visual meta-narrative that defies our exclusive individuality.

The first set, from 1991, is a series of solid forms that have been split and reassembled, with pipes piercing the solid and reaching out into the void, uniting one space with another. The surface of these works is rough with stone dust and iron filings, their colors earthy, rusty, and natural. Like Gustave Courbet, who mixed sand and dirt with his pigment to add a sense of authenticity and realism to his paintings, Barratt seems to emphasize the humanity of Christ and the reality of the incarnation through his use of dust and rust, as though dirt from the path that Christ trod has been ground into the works’ surfaces. Light reflects off the old music printing plates attached to the internal surfaces, raising a silent song of requiem and Easter hope into the void.

Nine years later Barratt produced a very different set of Stations for the millennium exhibition Stations: The New Sacred Art in Suffolk, England. Here there is no longer a diversity of forms merging and mirroring each other to evoke the narrative. Instead the drama is internalized within a uniform, cast concrete form: a solid figure-eight or infinity sign, a shape that suggests a human torso, or a cell on the point of splitting. It is a form Barratt has used before, when exploring the idea of breath.

Beneath the monochrome dull gray surface of the concrete, the viewer can catch a tantalizing glimpse of the events unfolding within, of broken bones and strained and scourged backs. The residue of an encounter seems caught on the surface like the face of Christ on Veronica’s cloth. Subtle forms erupt from within the concrete to express the emotional narrative of each event. In some works, the surfaces are crisscrossed with lines that seem to constrict and bind the form, evoking the scourged back on which the cross was placed. In Women of Jerusalem, a spine breaks through the center of the form, while broken bones seem to pierce the skin in Second Fall. In contrast, the surface of Christ before Pilate remains unmarked apart from a few blemishes, echoing the silence of Christ at his trial. Entombment concludes the journey by casting the form wrapped in a cloth, evoking the shrouded body lying in the tomb.

Vinegar has been poured over the concrete surface of each piece, leaving a sweat mark that testifies to passion and pain, and hinting at the vinegar offered to Christ on the cross. The hope that in the previous series came through the silent music of the printing plates is now carried in the subtle colors of the concrete and the gentle curve of the repeated form itself, whose resemblance to a newly fertilized egg hints at the promise of new life.

Barratt’s most recent Stations of the Cross set was created in 2004, and offers what he considers to be a retrospective of his work over the last fifteen years. Here the common form of the previous series has been replaced by a set of very different shapes. In Christ before Pilate, two identical white quarter spheres confront each other across a void (similar to Broken Whole at the Pheriche clinic), the narrative contained not in the forms themselves but in the silent, palpable tension of the void that both separates and unites them. In Wounds, a viscerally arresting oval of bright red, the surface is indented in a number of places, as if by a knife or nail, a reminder of the pressing of the void, that unformed space on whose edge the cross and death stand.

These Stations of the Cross engage us through the shared experience of earth, broken bones, labored breath, silence, wounds, and searching prayers, the common matter of the world. Language may divide us, but the shared experience of bodily existence is a bridge that transcends most divisions. In his most recent work, Barratt has started to explore this common thread, creating works that seem organic and corporeal in comparison with his earlier forms. The lumpen shapes of Reverie (2003) resemble cells, or globules of blood thrust into an uneasy alliance, as they seem to spin weightless in space [see Plate 9]. In Thinking Aloud (2005) this organic matter has disappeared, leaving only a skeletal rib-cage filled with air.

PLATE 11. Oliver Barratt. Feeling My Way, 2003. Steel, aluminum, resin, and paint. 51 x 43 x 31 inches.

PLATE 12. Oliver Barratt. Forty Ways In, 2003. Steel, fiberglass, aluminum tube, resin, and paint. 39 x 39 x 47 inches.

In recent years a new spirit seems to have emerged in Barratt’s work. His forms, which in the past have seemed pregnant with suggested life, have now given birth to line. Oozing out of the globules of Reverie are two curved lines that dance playfully in space for an instant before returning to the safety of their progenitor. The shape resembles the puddle of ink that collects on the paper before the artist allows the line to begin. In Feeling My Way (2003) little loops of polished steel also emerge tentatively from the surface, as if testing the air [see Plate 11]. By Forty Ways In (2003), the lines have erupted from the surface, leaving only the empty cones of their volcanic explosions [see Plate 12]. Forty ways in have become forty ways out; the lines are now released to draw dancing patterns in space.

PLATE 10. Oliver Barratt. Waterline, 2006. Painted steel. 13 x 23 x 13 feet. Catford High Street, South London. Commissioned by the Lewisham Council and Desiman Developers.

As we trace the journey of these lines, we find ourselves creating our own narrative; allowing stories and memories to unfold as our eye follows the line’s movement [see Plate 10]. It is an experience we share, not only with Barratt, but with everyone else who will construct narratives as their eyes trace the frozen track of the movements and gestures through time and space. We can never share these other narratives, but we are united in our tracing of the line as it traverses the void.

Barratt’s works defy their solidity, breathing and swelling with a sense of contained life. Their lines echo the flight of birds, tumbling and twisting like kites caught in the breeze, soaring out into space before returning to earth. They are a physical presence in the world, and yet these substantial works are celebrations of the insubstantial; their lines frame space, their forms contain the void, shaping and mapping it for us to contemplate. Where once we may have passed through space without noticing it, now we linger and dwell in it. Barratt’s work reveals the void as a place of mystery and substance, a place of reality that unites us all. For Barratt it is also a place of faith:

As a younger artist I was much more conscious of my own language and of my own subject matter, which was looking at my faith. As the work has matured though, I have become much less conscious. Now it is embedded within the whole structure and no longer needs to be brought to the fore. It is quite unselfconscious now, but central to my whole sensibility. A lot of my work is about the contemplation of uncertainty. But that is part of believing: the reconciling of things that you can’t quite see how they fit together.

This faith of the void has shaped his work from the beginning: the hesitant faith, which, like his pipes and channels, reaches out to the Other in hopeful prayer; the enquiring faith reflected in lines and pools that look for and hold onto spaces of mystery and wonder; and the expectant faith which waits for the inrushing breath of the Spirit to fill it, that Spirit that presses in on and transforms the hard surfaces of the world, leaving behind only gentle indentations as a sign of its unseen presence.