TWENTY-TWENTY WAS A CHALLENGING YEAR, to say the least. The world was thrust into a pandemic that affected every person on the planet, forcing governments, communities, and individuals to make difficult decisions about their actions and responsibilities. A reckoning with racial injustice further dismantled our assumptions about how and for whom our societies function. Differences and disagreements in our responses to this moment have stoked pre-existing divisions all around us.

From the crucible of the present, where the future is foreboding and uncertain, it is understandable that the past offers an appealing refuge. History appears far more stable than it ever actually was; even the recent past has aged rapidly under layers of rose-tinted patina. Indeed, nostalgia is all around us these days. Old films are constantly being rebooted, the eighties are in style, and home-baking traditions have been rediscovered in lockdown.

While seeking comfort in the familiar might seem simplistic, the ways we generate and consume nostalgia make it complex: how we perceive and connect to the past makes it an important medium for the cultural and political narratives which shape our communities. Art and popular media alike speak to how we fit the past into our present. A nostalgic way of seeing, hearing, and thinking profoundly shapes how we feel about the world around us.

What were once ordinary ways communities came together—worship, bars, celebrations, guests—have accrued overtones of danger. We have had to rethink how to connect with one another, and nostalgia plays an important role here: when we are able to see that others share our affinity for the past, and that we locate common values there, we gain a language for our contemporary communities. Though we often think of our nostalgia as being for an irrevocable past, it is actually about our present imagination and concerns.

Our communal attraction to nostalgia, our ways of fitting the past into the present, represent historical memory in flexible, complex, and often troubled ways. Sometimes we see this, and sometimes we don’t. Nostalgia’s simplification of the past is often overt and obvious, but our desires for the feel of a synagogue sanctuary or a Sunday brunch can be covertly nostalgic in ways we might not realize. Nonetheless, the relationship between history and memory remains constant: our nostalgia places our values first, then imagines histories which embody those values, independent of actual experience.

Shimon Attie. At Temple of Fortuna, 2002. Rome, Italy. On-location slide projection and lambda print. 50 x 60 inches. © 2021 Artists Rights Society, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Recognizing this relationship between community and history underscores that memory is perpetually flexible. The contemporary artist Shimon Attie speaks directly to this through his site-specific projections. In his series The History of Another (2002), he marks sites of memory throughout Rome by layering historical photographs on top of the city’s ruins. This activity emphasizes an ephemeral reality: in Attie’s words, “Like memory, the projection appears to have substance and materiality, but in fact it does not—it is only photons.” Neither the ruins nor the photographs possess meaning in and of themselves. They become active and present through our perception of them.

Attie highlights that history and memory are not joined by a common reality—by the fact that this person was here, or this action took place—but are connected through our own perception of the past. Nostalgia too, as culturally mediated memory, is defined by how we approach it, rather than what it refers to. This makes it a particularly useful way for communities to tell stories about their shared concerns and current aspirations. Whether we realize it or not, we say a lot about ourselves when we reminisce about what we find valuable within the past.

If the past is so flexible, perhaps we should think about how our current moment will age. Will we feel nostalgia for 2020? The question seems absurd. Why would anyone feel nostalgia for a moment synonymous with division, danger, and unrest? As the turn of the year approached and the pandemic wore on, the arrival of 2021 was imbued with liberating symbolism: warnings of “a dark winter” built our expectation for spring, while various vaccines promised “a light at the end of the tunnel.” If such momentum carries us out of the pandemic and into the future, who would want to remain attached to this year?

It is important to ask this question because, as Attie attests, the links between history and memory, memory and nostalgia, are not as intuitive as they appear. On closer inspection, many nostalgic periods reveal their roots in moments of similar distress. The 1950s’ quaint suburbia is yoked to McCarthy-era witch-hunts and the threat of nuclear war. Soviet kitsch evokes Stalin and gulags as much as it does patriotism. And some in Britain even fondly remember the Blitz as a time of national unity amid, or even because of, imminent peril. If Britons can feel warmly about a time when bombs were literally landing on their doorsteps, it does not seem so far-fetched that people may feel differently about 2020 further down the road.

While nostalgia often paints over history in broad strokes, it is not about burying the past. It is not as though hardship and pain simply vanish. Rather, suffering is placed in other frames of reference which de-emphasize it—or grant it a redeeming significance. These reactions capitalize on the fact that memory speaks to the present: our nostalgia is something which takes place in this moment. How people approach history is informed first and foremost by what they care about in the world around them, and this can outweigh the past’s more painful ordeals.

On these terms, looking closer at two specific nostalgic images can help to illustrate how present-tense concerns overcome painful elements of the past, digesting history into powerfully resonant narratives.

Russell Lee. In Front of the Movie Theater, 1941. Chicago, Illinois. Negative. 3¼ x 4¼ inches. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Bronzeville

During the Great Migration, millions of Black Americans relocated from the rural South to the North, Midwest, and West. New and extant Black communities grew rapidly amid the influx of internal migrants. Bronzeville, in Chicago, was one such place.

The image above was taken in April of 1941. Russell Lee, the photographer, was commissioned by the Farm Security Administration to document the movement of Black Americans toward the North, and he followed the path of migration to the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago. This image, taken on Easter, is part of Lee’s record of processionals, church services, and leisure activities that depict the liveliness and connectedness of the community. Here, as people wait in line for a matinée, their excitement and fashion give texture to this day in particular, and the life of the neighborhood in general.

These images are instrumental to how Bronzeville has been remembered by Black Americans. Later communities have gathered around this period as a testament of strength, culture, and capability. The vibrancy Lee depicts is reflected in contemporary visions of an historical Bronzeville—in paintings, public art, and exhibitions—that valorize the neighborhood’s economic and cultural success.

Yet all this came about because Black Americans were closed off in Bronzeville. As the neighborhood grew, pressure increased to prevent further racial integration with other areas of Chicago. Michelle Boyd drives this home in her book Jim Crow Nostalgia: Reconstructing Race in Bronzeville, where she describes how, beginning in the early twentieth century, “Whites responded to Blacks’ visibility and quest for economic and spatial resources by increasing segregation.” In large part, the authenticity perceived in Bronzeville’s Black culture is due to the forced concentration of Black Americans within this bounded space. Contemporary nostalgia tends to glide over this, highlighting the cultural value of these communities instead. In the neighborhood today, murals emphasize the strength of a cohesive Black community without dwelling much on why it was a minority enclave in the first place.

What does this say about nostalgia’s relation to the past? Are Bronzeville’s warm memories at risk if their historical picture becomes fully exposed? Not quite. Nostalgia, after all, is a contemporary way of approaching the past that puts a present community’s values first. The disjunction between nostalgia and history reveals not so much a deficiency of memory as a priority for what matters here and now. Looking to Bronzeville of the 1940s as a vibrant and cohesive Black community supports people’s vision of what a successful neighborhood looks like. In this context, the fact of segregation does not wholly vanish, but takes a place within a different narrative for Black communities.

These connections locate what is really important for nostalgic individuals and groups. Their nostalgia is about defining, envisioning, and supporting a perspective on history—on values, culture, and experiences—which connects with their contemporary concerns. This way of identifying what is valuable in certain nostalgic moments demonstrates how nostalgia is itself an inflected connection to the past. Even when that past includes seemingly insurmountable obstacles to this attachment, such as racial segregation, what is most important is where nostalgics find resonance and significance.

Kishinev

It is not always the case that nostalgic attachment to the past glosses over its challenging aspects, as with segregation or persecution. In some cases, that pain can be recontextualized as a meaningful feature of the nostalgia itself. This is how many Jews have valorized their eastern European, “old world” predecessors. Those Jews and their communities were shaped by anti-Semitic restrictions which opposed their integration and forced them to settle in specific areas. Nonetheless, later Jewish communities imagined those in the old world as forming a strong, authentic Jewish culture under that persecution. As with nostalgic reflection on Bronzeville, a situation of forced exclusion has been recast as a narrative about communal vibrancy.

Unlike nostalgia for Bronzeville, Jewish nostalgia for the old world embraces its very pain and trauma. While nostalgia for Bronzeville has recast the fact of segregation within an aspirational narrative, the way that these Jewish communities are depicted often stresses their crushing poverty and ongoing persecution. This suffering itself is part of how eastern European Jews are endowed with a nostalgic feeling of authenticity. One example is Ephraim Moses Lilien’s eulogization of terrorized Jews in Kishinev, now the capital of Moldova, ChiȘina˘u.

For three days in April of 1903, Jews were the target of unrelenting violence in Kishinev. This event garnered international attention; it was not only memorialized by artists such as Lilien, but was placed in context with other anti-Semitic riots which had occurred sporadically throughout eastern Europe. Kishinev was a particularly visible, disquieting example of the anti-Semitic prejudice which was a fact of eastern European Jewish life. However, outside of this historical context, Lilien’s engraving is especially resonant with the way that this violence was later woven into nostalgic narratives.

Now, Lilien himself had his own aims for his artwork, and was not especially interested in casting eastern Europe as a site of nostalgia, but the messages he advanced became important for later nostalgic perspectives. In this image, religious overtones dominate, not only in the angel’s invocation of the divine, but also in the man’s long beard, prayer shawl, and kippah. Jewish communities have come together around the idea that their eastern European heritage encompasses both persecution and piety, trouble and tradition. This figure and others like him are all part of how the old world is imagined as a coherent package. These connections do not make persecution good in itself, but they do make past persecution a necessary part of what becomes really important to later Jewish communities: as the historian Rachel Kranson writes, eastern European Jews’ struggle is nostalgically depicted “as the handmaiden of deep spirituality, intellectualism, and generosity.” And so, while nostalgia does not repress this struggle, it wholly recasts it from its immediate distress.

The way in which Jewish communities approach their heritage nostalgically lifts the pain of Lilien’s artwork into a different context. This perspective makes the Kishinev pogrom a pointed example of where violence and persecution mythologize eastern European Jews. This makes them special, holy, and authentic, which means that they can be embraced by later Jewish communities. The narrative here is no longer just about the violence in Kishinev but also about the values and strength that communities want to witness and represent in their own heritage and their own lives.

This kind of thinking about the past underscores that pain does not preclude nostalgia. We can feel warmly about moments that are hurtful and dangerous. We can feel affinity for times that we would not actually want to live in. What is most important to recognize in these sorts of nostalgic attachments is how negative details are contextualized and what they imply: whether they recall ongoing struggles, as with Bronzeville, or emphasize what people value within their nostalgia, as with Kishinev.

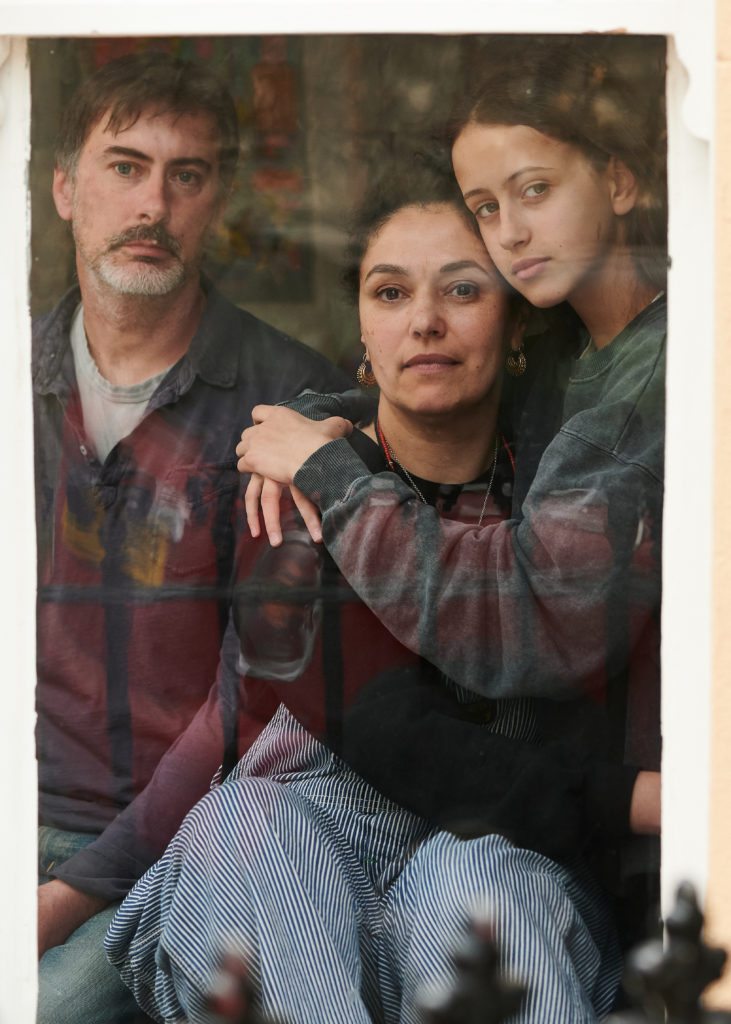

Sarah Weal. Ruth, Scarlett, and David, 2020. From the series Furloughed Friendship. Courtesy of the artist.

Lockdown

The pandemic has created a moment for which nostalgia at first seems incomprehensible. The daily death toll, the fear of infection, and the isolation that characterize this moment have left us with an overwhelming desire to get out of this situation. For many, lockdown epitomizes the worst of this pandemic. It disperses communities, cutting people off from family and friends, care, and even basic resources. This challenge is very real. It is important not to take away from that.

But it is also important to think about how the memory of this moment will develop in the future. At present, we are standing inside of the pandemic, and so its bitterness defines how we feel about it. However, as we can see from other examples, these things change as they age. Nostalgia teases certain narratives out of history, and nostalgia is beholden to the present over and above the past. This may mean that our lockdown’s isolation will be underplayed, like segregation in memories of Bronzeville, or that it will be recontextualized, like the persecution of eastern European Jews. Already, artists are reflecting on the pandemic and considering how it resonates in our society.

In British photographer Sarah Weal’s series Furloughed Friendship, a personal project undertaken during lockdown, windows feature prominently. Severed from the outside world, and from Weal herself, her subjects exist in a space of insurmountable isolation. The transparent window becomes a divider; its reflectiveness serves to remind us of this separation. However, Weal also captures the way people are living with novel relationships on their side of the glass. Her subjects’ gestures and contact speak to their connectedness, even as their gaze is directed toward the viewer, and this reflects one dynamic of lockdown. We often think of Zoom calls as this pandemic’s involuntary heritage, but the sheer amount of time spent with one another is an equally important change.

While the word “lockdown” still rightly evokes isolation, it is possible that in the future it will be placed within a larger narrative that emphasizes closeness. This is not to say that we will have warm feelings about lockdown—proximity, after all, is not a positive thing in and of itself—but rather that we may come to ascribe an important value to these experiences. It is because nostalgia trades in the communal and the narrative that this is possible. The question is not so much, “Will we feel nostalgia for 2020?” as, “What will shape the nostalgia of the future?” What new factors will inform the way we feel about turning to the past?

Some may dislike this nostalgic habit, sensing an arbitrariness to the stories it tells. But does nostalgia’s reshaping of the past really represent a disconnect with history? Not necessarily. Nostalgia does not show that “real” history is different because it is neutral; rather, it illustrates that no past is neutral, that nostalgia and history alike must be taken seriously. We must embrace the fact that our memory is informed by what we care about in the present. As we reflect on our present experiences, we do well to consider how our hardship will become meaningful in the future, and for whom.

Elijah Teitelbaum is a researcher at the University of Cambridge. His work focuses on connections between nostalgia and visual culture, and especially how American Jewish communities perceive and represent their histories.