THIS ALL HAPPENED IN 1998. A youngish woman, an artist, was at home in her council flat in the Waterloo neighborhood of central London. Council flats, you should know, are basically a British version of public housing. The woman’s name was Tracey Emin. She was having a lousy week.

A relationship had gone sour. More deeply than that, life had gone sour. Depression set in. She started hitting the bottle pretty hard. She couldn’t get out of bed. She smoked. She drank more. She snacked on junk food, rarely leaving the increasingly rank confines of her boudoir. This went on for days.

When she finally emerged from her downward spiral, Emin gazed upon what her drunkenness and depression had wrought. The bed spoke volumes. The rumpled and stained sheets were a testimony not to a good night’s sleep, but to despair. Next to the bed, piles of junk from her daily life. Empty bottles of vodka. A pair of dirty slippers. Cartons of cigarettes and other trash. A pair of panties soiled with menstrual blood. A container of birth control pills. Condoms.

A normal person would have wrapped all the trash up in the dirty sheets and thrown the whole lot in the rubbish bin (as they call it in Waterloo). But Tracey Emin was not then, and is not now, a normal person. As she recovered from her depressive bender, Emin had an interesting and unexpected thought: “This is art. I’ve created a work of art.”

Tracey Emin. My Bed, 1998. Mixed media. Dimensions variable. Tate, loan from the Duerckheim Collection. All images © 2016 Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS, London / Artists Rights Society, New York.

The whole sordid scene became just that, an artwork displayed more or less exactly in the condition it was in when Emin finally emerged from bed that fateful day in Waterloo, 1998. That’s to say, Emin took the bed, the rumpled and stained sheets, the junk strewn all around it, and simply displayed that very stuff, unaltered by any other sort of artistic craft, as art.

In 1999, Emin’s bed, now titled My Bed, was displayed at the Tate, one of England’s most prestigious venues for contemporary art. My Bed had been singled out as a finalist for the Turner Prize, England’s most coveted prize for contemporary art. A big deal all around.

The press immediately did what the press is expected to do in such cases. It went wild. The controversy machine sprang into action. The artwork was denounced as filthy, disgusting, and immoral, not even really art. Some declared the work a sign of feminism’s demise, or art’s demise, or civilization’s demise. It was pointless sensationalism. It was boring and self-absorbed.

Tracey Emin. My Bed (detail), 1998. Mixed media. Dimensions variable. Tate, loan from the Duerckheim Collection.

Much as this criticism and controversy may have stung, it couldn’t have come as a complete surprise to Tracey Emin. She’d already been carrying on as a member of the so-called YBAs (Young British Artists, which claimed as members other well-known figures like Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas). The YBAs were, in 1997, enjoying the sensation created by their group exhibit at the Royal Academy of Art called Sensation. Sensation went on to create a stir when it traveled to New York, where then-mayor Rudolph Giuliani strenuously objected to Chris Ofili’s painting of the Virgin Mary rendered partly in elephant dung.

Emin made a television appearance around the time Sensation was showing in London. It was a talk show hosting a discussion about contemporary art (BBC 4). As fate would have it, the show was live. Emin was quite drunk. The cameraman kept trying to pan away from her as she kept trying, ever more desperately, to talk. Finally, she burst out with a now-infamous soliloquy:

I am the only artist here from that show Sensation. I want to be with my friends. I’m drunk. I want to phone my mum. She’s going to be embarrassed by this conversation. I don’t care. I don’t give a fuck about it.

She stormed off the stage and into the London night. Many thought (and not a few of them openly hoped) that Emin would continue to storm off, all the way out of art and out of the public consciousness. But she did not. The year after her live television performance, she was in the news again with My Bed.

My Bed has also refused to bugger off, showing up at galleries and museums around the world for more than fifteen years. The work manages to continue its hold on the public consciousness. It was purchased by a collector for 2.5 million pounds in 2014 and was back on display at the Tate in 2015. This time My Bed was exhibited next to paintings by Francis Bacon. The Tate show’s curator Elena Crippa said of My Bed, “I think it certainly holds its power and it was a wonderful experience to see it literally unfold in the room.”

In exploring the resilience of Tracey Emin the artist, we might say a little something more about Tracey Emin the person, especially since the two so often overlap. My Bed is really her bed, the bed that was created out of that awful week in her actual life. This is personal art. Indeed, all of Emin’s work emerges directly from her own experience. This is notoriously the case in her other most famous work, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995. That work consists of a tent, the kind you’d use to go camping. Inside are the hand-stitched names of all the people Tracey Emin slept with from 1963 to 1995. It’s a work that, like My Bed, is guaranteed to get a rise out of people. It crosses a number of boundaries, making so shamelessly public what is generally kept private.

Critics and commentators predictably dismissed the work as a provocative bit of sexual exhibitionism. But this was to miss something of the point, since plenty of those named in Everyone I Have Ever Slept With were people with whom Emin had never had sex. The work wasn’t about sex. It was, literally, about sleeping, about the intimate act of lying in bed, asleep, with another person. Such a thing might very well happen post-coitally. But often enough, it does not. One of the names was, after all, the name of Emin’s grandmother. Of her grandmother, Tracey noted, “I used to lay in her bed and hold her hand. We used to listen to the radio together and nod off to sleep. You don’t do that with someone you don’t love and don’t care about.”

This comment gives us another clue to the artwork of Tracey Emin. It is work that often comes off as shocking, sensationalistic, and emptily confessional. But further probing reveals, more often than not, another layer. The word “confess” comes from the Latin verb confiteor: “I acknowledge,” “I avow,” “I concede.” Emin’s artwork is almost always engaged in some act of acknowledging, avowing, and conceding. Emin often creates artwork out of words. Frequently, these words appear on fabric, blankets, and pillows. The sayings are penned in her trademark scrawl, with its imperfect grammar and atrocious spelling. The sayings can be disarmingly softhearted, verging on the sentimental, and are presented utterly without irony.

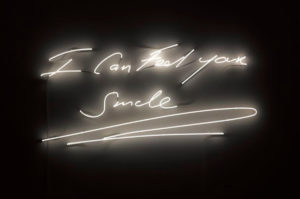

A neon sign Emin created in 2005 reads, “I can feel your smile.” A fabric print (also from 2005), which features a rather pathetic bird sitting on the branch of a tree, reads, “I am not just sad, but also lonely.” A blanket made to hang on the wall contains hand-cut letters that spell out the sentence, “Theres no one in this room who has not thought of killing.” Another fabric work reads, “Sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry.” The phrase “believe me, I am,” has been crossed out. There are dozens more examples along these lines. Each of them repeats, at its core, in one way or another, the essential sentiment: “I am experiencing suffering. I acknowledge, I avow, I concede.”

Emin’s suffering is often experienced in the bedroom. Sometimes, this is because sex occurs in the bedroom, and having sex with other people can be, for many, a source of later suffering (or for that matter, and depending on the person you’re in bed with, present suffering). One of her embroidered blankets from 2009 shows a woman, presumably Tracey, lying in prone position while an ignominious male figure ruts away on top of her. The caption above the scene reads, “is this a joke.” When Emin deals with sex, she can be quite funny. She can also delve down into the heart of trauma. Emin was raped in her teenage years. This fact, in various guises, makes an appearance in her art from time to time.

But it must be made clear that most of Emin’s work is not about sex, either as joke or trauma. Quite a lot of her work, however, is about the bedroom.

Tracey Emin. Sleep, 1996. Monoprint and stitched label on cotton pillowcase. 19 1/2 x 28 3/4 inches.

Back in 1996, two years before My Bed, Emin stitched the words “Tracey Be Brave” on a pillow (Sleep, 1996). In 2002, she created a work called To Meet My Past, with another bed in it, this one a four-poster job. On the bedsheet she scrawled the words “I cannot believe I was afraid of ghosts.” Nearly every exhibit Emin has put together since her Turner Prize days has contained some explicit reference to the bedroom and what goes on there.

Perhaps it is safe to say, then, that Tracey Emin is an artist fascinated with sleeping and with beds. And why not? We are all asleep for about a full third of our lives. Being in bed is a fundamental condition of being human. Of course, the problem with being in bed is that much of the time we’re not really there, or we’re there in a way we don’t fully understand. That’s because we’re asleep. The body is in the bed but the mind is elsewhere. It is unconscious. Or it is engaged in the act of dreaming and so not in bed at all but off on the wild nocturnal escapades that are the mind’s nightly prerogative. Going to bed is thus the act of giving yourself away to a mysterious process, surrendering to the lack of control that constitutes falling asleep. That’s why we call it “falling” asleep.

To be in bed is to be in a vulnerable state. To share a bed with someone is to invite another person into the realm in which we are most exposed, in which we are the least able to defend ourselves. This can make the bedroom a fearsome and exciting place. It is a place of potential revelations. To enter someone else’s bed or to be in someone else’s bedroom is like walking inside the boundaries of another person’s subjectivity. It’s to penetrate that amorphous threshold that separates the self we project to others and the self we protect behind a veil of privacy.

The bedroom can therefore be thought of as the place where the true self hides, be it our own self or the self of someone else. But here’s where it gets even trickier. That’s because the self that is revealed in the bedroom is so elusive. It is easy to gaze upon the visage of a friend or lover lost in sleep and pretend you are seeing that person in their pure, unvarnished state. But what are you really looking at when you see a face asleep? You are looking at a blank mystery. The self isn’t really there at all.

The idea that the self hides in the bedroom is but a short step from the idea that the self is always hiding, wherever it is to be found. Maybe the self doesn’t just hide; maybe it can never be found. Maybe it doesn’t “exist” in the way that other things exist. The self is completely without the stability that we falsely ascribe to it. It is, perhaps, nothing but a fabrication held together by our cherished memories, our favorite pictures on the wall, our coziest blankets and pillows, our family mementoes. Or, in philosophical language, “the Self is the fetishized illusion of a substantial core of subjectivity where, in reality, there is nothing.” That’s how Slavoj Žižek puts it anyway, following Jacques Lacan.

What I’m trying to say here is that the bed is quite a good symbol for some of our most troubling and intractable metaphysical problems. Questions like, “Where am I?” or “Where is my ‘me-ness’ located?” or “Where’s the me that’s really me?” or “Where is the true me?”

From these spiral out a number of related questions like: “Is the real me in my head, my brain, my mind?” and “Am I fundamentally an embodied thing or does the real me transcend the physical form?”

We are not going to solve these tricky metaphysical conundrums here, I’m afraid. Anyway, it is not the primary purpose of art to do philosophy or to speculate about metaphysics. It is the job of art, however, to give physical form to compelling nuggets of our shared experience. And there’s no doubt that we all share in the mysteries of subjective consciousness, whether you come to consider the problem of how “you” are “you” through Lacan, or Žižek, or Pascal, or Paul, or by being an especially sensitive woman raised in Margate on the southwest coast of England.

As to Tracey Emin’s ruminations on the nature of the self, the crucial thing to notice about My Bed is that Emin is not in the bed. She rose, and in rising she gained the perspective that allowed her to see the bed as something more than just a hygienic disaster area. She rose, and looked, and saw. What she saw was testimony to the despair of a spiritual bottom. That testimony was only able to speak its truth after she got up, after she’d broken the grasp of that bed. She was only able to recognize the bed fully as her bed once she’d become physically absent from it.

And yet, at the same time, she is still there. You can—and I don’t mean to be disgusting here—practically smell her in that bed. Her presence is manifest in the rumpled, stained sheets. My Bed looks like Emin’s bed as she left it just a minute ago, maybe to get up and go to the bathroom. The presence and the absence, that’s what is compelling about the work after the surface titillation wears off. This is undeniably someone’s bed. A real someone. A genuine person who slept here and therefore made this location most intimately her own. Because Emin was so honest in showing us the intimate and otherwise-embarrassing elements of her life in My Bed, the work carries authentic testimony of her genuine presence. But it is absence that creates the central tension of the work. It’s hard to give a name to that tension. Perhaps we can call it an ache. The absence of Tracey Emin from her bed makes the work ache.

Other artists have noticed that an empty bed aches. Walker Evans, for instance. Evans took a picture in 1936 of a bedroom in the cabin of a man named Floyd Burroughs in Hale County, Alabama. The bed has a metal frame, a clean white sheet, and two pillows. You can see the rough wood slats of the cabin walls behind it. The institutional (hospital?) quality of the bed against the down-home look of the cabin adds an element of dread to the photo. The emptiness of the bed asks questions. What’s gone wrong here?

Walker Evans took another photograph of an empty bed in a boarding house on Hudson Street in New York City sometime between 1931 and 1933. The photograph carries an extra charge because the bed belonged to John Cheever. But Cheever is not in the photograph. Walker Evans wanted the bed, not the man. Of course, in not getting the man, Evans got the man. That’s because Cheever, though absent, is fully present in that room and, especially, on that bed. The room is tiny. The ceiling is claustrophobically low. The window, with its thin, grimy drapes pulled across a dark blind, might as well not exist. This room is not meant to see the light of day. (There is another version of the photo with the window open that is less effective). It is a dingy lair. The bed is small with a wire metal frame and a rather pathetic excuse for a mattress. The whole bed is so bowed that, incredibly, it creates what is like the spectral image of the human body that sometimes lies on it. It’s as if the bed has a ghost.

The absence of Cheever’s body speaks of absence in general. This absence is not light or airy. Cheever’s bodily absence is heavy, so heavy that the bed is indented with it. What is heavier, after all, than a body asleep in bed? The bed is marked with the heavy presence of Cheever’s body, which, presumably, flops down into it night after night. But even this nightly heaviness does not last. The minutes on the clock tick by. The body wakes up. The body arises and goes away, leaving the bed so disastrously empty. Looking at Evans’s photo of Cheever’s bed, the thought bursts to mind, “There is no amount of human presence that can outweigh the inevitable absence.” This is literally true. John Cheever had a strong presence in that little room on Hudson Street. But he’s dead now. When you look upon this picture of his bed in the 1930s you are looking upon a testimony to a body that is fading, as bodies do.

So here is the discomfiting duality of a bed. Cheever’s bed, as Evans photographed it, is saturated with the context and condition of his life as it was actually lived. There’s a lot of life in his bed, in any bed. Just look at the tousled sheets of Emin’s bed. Life, activity, motion, struggle. But beds are also a foreshadowing of death. Every bed is a sepulcher and a grave. Every bed is a cold slab waiting for the moment when our presence fades into absence. Every work of art, therefore, that presents us with an empty bed in an aesthetically satisfying way is tapping into roots saturated with spiritual significance. There’s no other word to use. Spiritual because we are talking about mortality and about the oddness of being creatures created both to live and to die. Both to live. And to die.

Gaze for a moment upon the pictures Van Gogh painted of his bedroom in the little yellow house in Arles where he lived, for a short time, with his impossible friend Gauguin. He made three during the years 1888 and ’89. The second is, to my mind, the best. But in all three, it was Van Gogh’s specific genius to be able to paint a room as if it lives and breathes. This was achieved by means of his famous brushstrokes, his indifferent and chaotic sense of perspective, his intense use of color. The room Van Gogh painted vibrates with a sense of human presence, as thousands of museumgoers have noted thousands of times over the generations.

In Van Gogh’s bedroom is a bed. Like Cheever’s, like Emin’s, it does not contain the body. For all the life that Van Gogh painted into that picture, it also marks his absence. The final painting in the series was painted in 1890. That same year, in July, Van Gogh shot himself in the chest. The gunshot didn’t kill him immediately. But by the next day, he was dead. Looking at the bedroom painted in the year that Van Gogh was about to die, it is impossible not to see that bed as a harbinger of death, as a testimonial to the final absence that is just around the corner for Van Gogh. The painting says, “This room, this bed, is more permanent than I am.” And then it asks a question. “What of me remains within it? In what way do I remain?”

The contemporary painter Christoph Hänsli has also painted a number of empty beds. In 1994, he painted rooms in a small hotel in Paris. The rooms are lonely, as Hänsli painted them, lonely as only hotel rooms can be. In several of the paintings, we see two empty double beds and a vast expanse of antiquated wallpaper dominating the tops halves. The empty rooms and beds await the bodies that will come and go.

Hotels see so much human presence, different people night after night, that the constant presence becomes absence. It stops mattering who was there. It could be anyone in that room. Haven’t we all had the following train of thought at least once, late at night in a hotel room? The first thought: “I could be anywhere.” The next thought: “Anyone could be on this bed. I could be anyone.” The final thought, a question: “Why am I me, and not some other bag of living flesh?” is but a version of the Ur-question, “What will happen to me when I die?”

John Berger wrote a short essay about Hänsli’s bed paintings. The essay culminates in the following lines, which are written like a letter addressed from Berger to Hänsli:

One of your canvases is…of an unmade bed and a crumpled duvet. The infinite wall is behind. For centuries painted sheets and draperies have featured in European art. Danaë reclines upon them. The body of the dead Christ is laid out on them. They receive the marvelous body and are moulded by it. But here there are only traces, only an absence.

I was here. And now I too have left. There is nobody.

There is nobody. There is no body. The pun gets at the intractable metaphysical problem. Because even when there is a physical body in the bed, it is hard to understand how that physical body is related to the “somebody” that hides within. And it is hard to understand where that “somebody” goes when the body goes. Is there somebody when there is no body?

Berger’s thoughts wander through art history and finally to images of the dead Christ. He’s probably referring to one famous painting in particular. That’s the Lamentation of Christ, or the Dead Christ, painted by Andrea Mantegna around 1480. You’ve seen the image before. Christ is laid out on a slab that is also like a bed. There is a pillow. There is a sheet, the intricate folds of which cover the bottom half of Christ’s corpse. Christ is dead, just taken down from the cross.

The painting is famous because Mantegna performs some pretty incredible painterly tricks to show us Christ lying, feet toward us, on that slab. These tricks of linear perspective and foreshortening were relatively new at the time. Dead Christ is therefore something of a show-off piece, a tour de force in the technology of painting circa the mid-fifteenth century.

It is also, of course, something more. New technologies open up new possibilities. In the fifteenth century, the new possibilities were in the direction of painterly realism, a mirror-like correspondence between the image in the painting and the way things actually look. Christ’s body, as Mantegna painted it, looks like a real human corpse lying on a slab. The puncture marks in the hands and feet are especially persuasive. This is a dead body, the dead body of a recently crucified man.

That is what disturbs the mind, especially the religiously faithful mind, in looking at Mantegna’s painting. Christ is so very, very dead. Mantegna’s Dead Christ is a precursor to a later painting by Hans Holbein the Younger (The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, 1520–22). Never has a dead Christ looked deader than as Holbein paints him. The flesh has already begun to rot. Holbein’s Christ is so overwhelmingly dead that Dostoyevsky would later dedicate a famous passage to the painting in The Idiot. In Dostoyevsky’s book, a guileless Myshkin comes across a copy of Holbein’s painting in the guileful Rogozhin’s home:

“I like looking at that picture,” muttered Rogozhin, not noticing, apparently, that the prince had not answered his question.

“That picture! That picture!” cried Myshkin, struck by a sudden idea. “Why, a man’s faith might be ruined by looking at that picture!”

“So it is!” said Rogozhin, unexpectedly.

There’s a simple reason why Holbein’s picture might shake a man’s faith. Looking at a Christ so indisputably dead makes it hard to believe that this body comes back to life again. That’s to say, with Mantegna and Holbein, we confront an image of death that undermines the idea that Christian faith abolishes the problem of death. Looking at the dead Christ as Mantegna and Holbein paint him, the question comes urgently to mind: “What is this promise of eternal life, exactly?” It cannot be that death is just a pause in our infinite living, can it? A brief nap, and then we wake up to become ourselves again on and on into infinity?

To be fully human, fully awake, is to confront, in the dark and deepest hours of the night, the idea, the painfully all-too-real realization, that my inner me-ness is a tenuous tissue that barely exists and is quickly swept away, like chaff blown by the wind. Or, as Gerard Manley Hopkins put it in his poem, “No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief.”

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne’er hung there. Nor does long our small

Durance deal with that steep or deep. Here! creep,

Wretch, under a comfort serves in a whirlwind: all

Life death does end and each day dies with sleep.

The Christ who lies on the slab, the Christ who Mantegna and Holbein painted, that Christ surely experienced the same mental struggles as Hopkins. He too must have hung there on the cliffs of fall. He must have, if he was fully human. And what is more human than to die? So, Christ must really and truly have died. That’s what Mantegna and Holbein captured in their pictures. They captured a Christ who is not playing dead, but who is really dead. The dead Christ is presented in the most fully human moment of his humanness. But how strange that this most human moment, the moment of finitude, the reality of death, is also the point at which Christ (and anyone else) is most absent. The point of extreme subjectivity is also the point at which that subjectivity disappears. Where is Jesus, the Jesus who was living and breathing but a few hours ago, in relation to this lifeless corpse?

Christ, in the Dead Christ paintings, is not a solution to the problem of death. He is a participant in the problem of death. To think of Jesus as the Christ, as the one sent from God, as God, is to think of God as participating in the problem of death. It is to provide evidence, in the image of a corpse who is God, that God dies with us and that we are all, in a sense, the constant dying of God. This does not unravel the mystery of death. It does not solve the problem of death. It deepens it.

What Dead Christ, or My Bed, or Van Gogh’s painting of his bedroom says visually is what Karl Rahner tried to say once with words. Namely:

But the affirmation of faith concerning the definitive ending by death of the state of pilgrimage means, as well as the survival of man’s conscious personal existence, that the fundamental moral decision made by man in the mundane temporality of his bodily existence, is rendered definite and final by death. This doctrine of the faith involves taking this earthly life with radical seriousness. It is truly historical, this is, unique, unrepeatable, of inalienable and irrevocable significance.

§

Tracey Emin took My Bed out of storage in 2014. She was getting it ready for the Christie’s art auction in which it sold for the aforementioned 2.5 million pounds. She described to The Guardian what it was like to prepare My Bed for public exhibition again:

Today when I took the duvet out, it was flat. And when I threw it on the bed, it didn’t look right. So I fluffed it up, and it still didn’t look right.

So I actually made the bed and got in and pushed the cover back so it had that natural feeling that a body has been into it.

It is strange because it still has that same smell that it had sixteen years ago.

Obviously the stains and everything else are touching me, and it’s like being touched by a ghost of yourself.

In a sense, the Tracey Emin who lay in that bed in 1998 is already dead. Emin turned fifty in 2014. She’s not the sensitive young woman from Margate anymore. She is someone else, as are we all, given the passage of fifteen years. The self flees, even from the self.

One day, the self will flee its final flight and Tracey Emin will die. At that point, My Bed will have fully come into its own as a work of art. The tension between presence and absence will have reached its peak.

As of this moment, however, Tracey Emin is still very much alive. Recently, she has turned from installation and fabric work back to drawing and painting. She makes a lot of self-portraits. In these, she lets the brush trace the outlines of her body, as the folds and indentions of the sheets and bedcovers once did. In an interview with Rachel Cooke, Emin described what she’s doing like this:

I’ve gone from being a really thin girl—even when I was forty, I was thin—to becoming matronly and womanly. I’m trying to come to terms with the physical changes. There’s a big difference between being thirty-five and fifty. Massive.

And that’s what I’m trying to understand. Where does that girl go? Where does that youth go? That thing that’s lost, where has it gone? I’m looking for it in the pictures; I’m looking for it in the paintbrush.