IN THE MID-1980s, just shy of my fortieth birthday, I found myself out of work and divorced. It was a crash landing of all my aspirations, and crawling from the wreckage of two traumas, I was grieved, confused, desperate—cut off from the world I thought I understood. In the fragile years that followed, I tried to sort out how these things had happened and construct a new life for myself as I entered middle age. Thankfully, though slowly, new pieces were added to the gaps in my broken life, and while my hope returned as things seemed to repair, a new anxiety emerged: following my crises, I felt I was no longer certain what it meant to be a man in late twentieth-century America.

Nor was I the only one who harbored this apprehension. Male relatives, friends, and colleagues confided that the expectations they had grown up with no longer held. I suspected something larger was at play than my personal disquiet. So I looked outward at the social terrain and discovered a variety of expressions and tendencies that spoke to the vexed status of maleness. American men from all walks of life appeared to lack an authentic masculine way of being in the world, whether relating to women, children, other men, or society at large. Moreover, the rise in destructive or dysfunctional (a byword coined during that era) behavior by males seemed to grow out of a disintegrated masculinity that was caused by economic shifts, cultural changes, and a break with past traditions. This was the aimless and ugly underside of the blue-collar tribe of male protagonists brilliantly portrayed in the blockbuster film Saturday Night Fever. Cinema is often the best mirror of current trends. As one example, starting in the 1980s, actor Nick Nolte built his career playing lost, damaged, and despairing men—as well as occasionally acting out his personal problems in public.

Facing their anxieties about masculine identity, many men looked for reassuring counsel, new bearings, and fresh voices. For educated, middle-class males, avatars included cultural critic Michael Ventura, psychologist James Hillman, and poet-musician Robert Bly (remember Iron John, and drumming circles in the woods?) The “ordinary guy” audience was targeted by the Promise Keepers, a movement that blended evangelical Christianity with sports culture and staged emotionally cathartic mass gatherings in athletic stadiums to achieve a breakthrough to a redeemed masculinity. Excellently summarizing these and many related issues was Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, by the feminist and Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Susan Faludi. Appearing in 1999 (and still in print), it stands among the better chronicles of America’s fin-de-siècle masculine identity crisis.

Robert Longo. Untitled, 1981. Charcoal and graphite on paper, silkscreen ink, tempera on paper. 60 x 96 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.

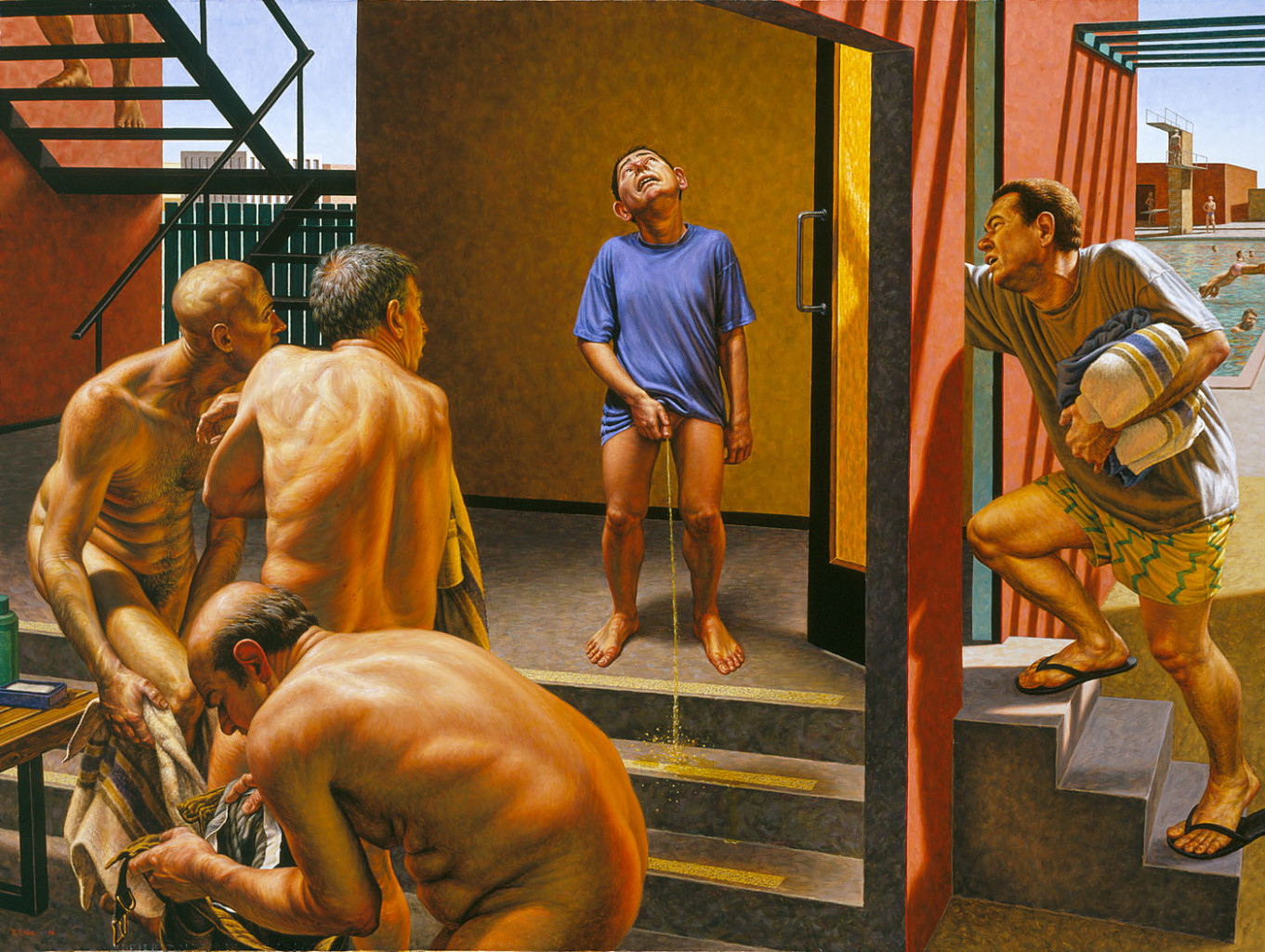

As a curator and art writer, I expect social and cultural trends to find their expression in the work of contemporary artists. The 1980s saw a number of provocative works that portrayed men in crisis and behaving badly. Among the best-known artists were Jonathan Borofsky, Leon Golub, Robert Longo, and Jerome Witkin. Borofsky produced works parodying American societal archetypes, especially notions of macho superiority. Golub painted stark, acrid narratives of mercenaries, torturers, and death squads—the incarnations of American counter-insurgency policies during the Reagan administration. But Golub’s figures were not identified with any specific political or historical event; rather they depicted what men can devolve into when—apart from society’s regulations—they form violent bands and seek victims. (See especially his White Squad series.) Longo focused on New York’s corporate culture; his series of monumental drawings, Men in the Cities and a sculptural triptych, Corporate Wars: Walls of Influence, displayed the competitive violence (and its casualties) he saw submerged in the psyches of aggressive young businessmen [see plate]. Witkin is among the most ambitious and socially attuned narrative painters, producing huge sequential works with an intense theatricality [see Image #11]. His multi-panel A Jesus for Our Time is a satirical response to the rise of rightwing, white, male televangelism in the 1980s. The young protagonist (named Jimmy) is a self-made, media-style “Jesus,” attired in a glaring white suit, who tragicomically projects himself into a world of which he is ignorant and has earned no right of entry. Clueless, he does not anticipate the violent, explosive outcome, and is devastated.

Troubled and questing masculinity wasn’t just an eighties thing. Neither did it end at the millennium, when Faludi’s Stiffed appeared. The conditions that unhorsed so many American men, if anything, have grown worse with the mortgage and investment crisis, and its aftermath, the deepening recession. Nearly a decade into the twenty-first century, the arts continue to reckon and reflect upon masculine disquiet and search for meaning, prompting revivals of Arthur Miller’s sixty-year-old classic Death of a Salesman, relevant again. In film, clear-cut masculine purposefulness and idealized martial virtue were at the core of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, as well as the grittier Band of Brothers, HBO’s World War II series, produced by hero-hungry baby boomers.

In the fine arts, a new wave of visual artists continued to engage the subject of problematic masculinity. In southern California, where I have spent most of my professional life, I became acquainted with F. Scott Hess, one of the west coast’s leading figurative painters. Recently, he has focused his mid-career on a grand academic-style narrative opus of “historical” masculine underachievement and failure based on a largely faux familial chronology that parallels the history of the United States. His motive? Hess says he has never forgiven his father’s abandonment of the family when he was a boy, and is turning this betrayal into epic art where the sins of the fathers are passed on to the sons. In conversations about his work, he always makes sure you know he is a confirmed atheist, but many of the human and male dramas in his tableaux are haunted by what I would call the strangely absent presence of the divine, as well as fathers gone MIA. Hess’s The Pissing Boy is a tableau of male shame and desperation. It depicts a forlorn child urinating in the middle of a locker room while looking pleadingly into the empty heavens. The man charging into the scene at right is a self-portrait of the artist, arriving too late [see plate].

Guy Kinnear is also from southern California and, like Hess, a painter who deals with the masculine predicament. He is about fifteen years Hess’s junior—a generation X-er. Unlike Hess’s complex historical mise-en-scenes, Kinnear’s stark compositions of one or two male figures are existential in tone. Moreover, almost alone among artists who are mining male issues, Kinnear is producing work that reflects a committed theological stance, and a sense of hope.

In Kinnear’s recent painting Our Daddy, from his series titled Pater Noster (the Latin name for the Lord’s Prayer), a burly male figure sits up on a bed in a gloomy interior [see front cover]. He faces away from the viewer, extending his arms to a window open to a clear blue sky. On one hand, the scene is ambiguous: what is this man doing? On the other, we recognize a primal religious gesture: reaching up to the heavens in prayer, the realm of the archetypal “sky father,” a deity in a number of religious traditions. This is something quite different from the quietly receptive, inward-looking posture of prayer seen so often in religious painting—attitudes that some popular devotional art of the past two centuries has exaggerated and saccharinized in a way that ties physical expressions of devotion to a narrow, stereotypical kind of femininity. Rather Kinnear’s implorante welcomes an embrace with the divine, a type of Jacob ready to contend with the Man for a blessing. Painted in a toned-down neutral palette with a robust immediacy, Kinnear’s image places masculine identity in the very act of initiating a transcendent encounter. Further, the artist’s title, Our Daddy, announces the tender parental nature of the connection of a man to his God.

Kinnear grew up on California’s central coast and was raised in a Catholic home where he became comfortable with religious visual culture. Wanting to clarify his faith, he affiliated with evangelical Christianity during his adolescence. Kinnear also felt a vocation to the visual arts, majoring in studio art as an undergraduate and earning a degree from southern California’s Azusa Pacific University, where he now teaches. His attitude toward the realm of mainstream contemporary art was a mix of curiosity and avoidance, but he realized that if he was to be taken seriously as an artist, he needed to approach it. “I knew I had to expand my perspective to learn from the plurality of popular culture and the larger art world,” he says. In 1995 he was accepted into the MFA program at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he made a rapprochement with postmodernism. To be sure, this meant the loss of some youthful certitude, but ultimately, his graduate experience challenged him to integrate his Catholic past with his evangelical faith and be in dialogue with current theoretical issues about the body in art and the ongoing exploration of masculine identity. For Kinnear, the outcome was salutary. He earned a place in the contemporary art arena at a time when figurative painting was undergoing rehabilitation and heading in new directions.

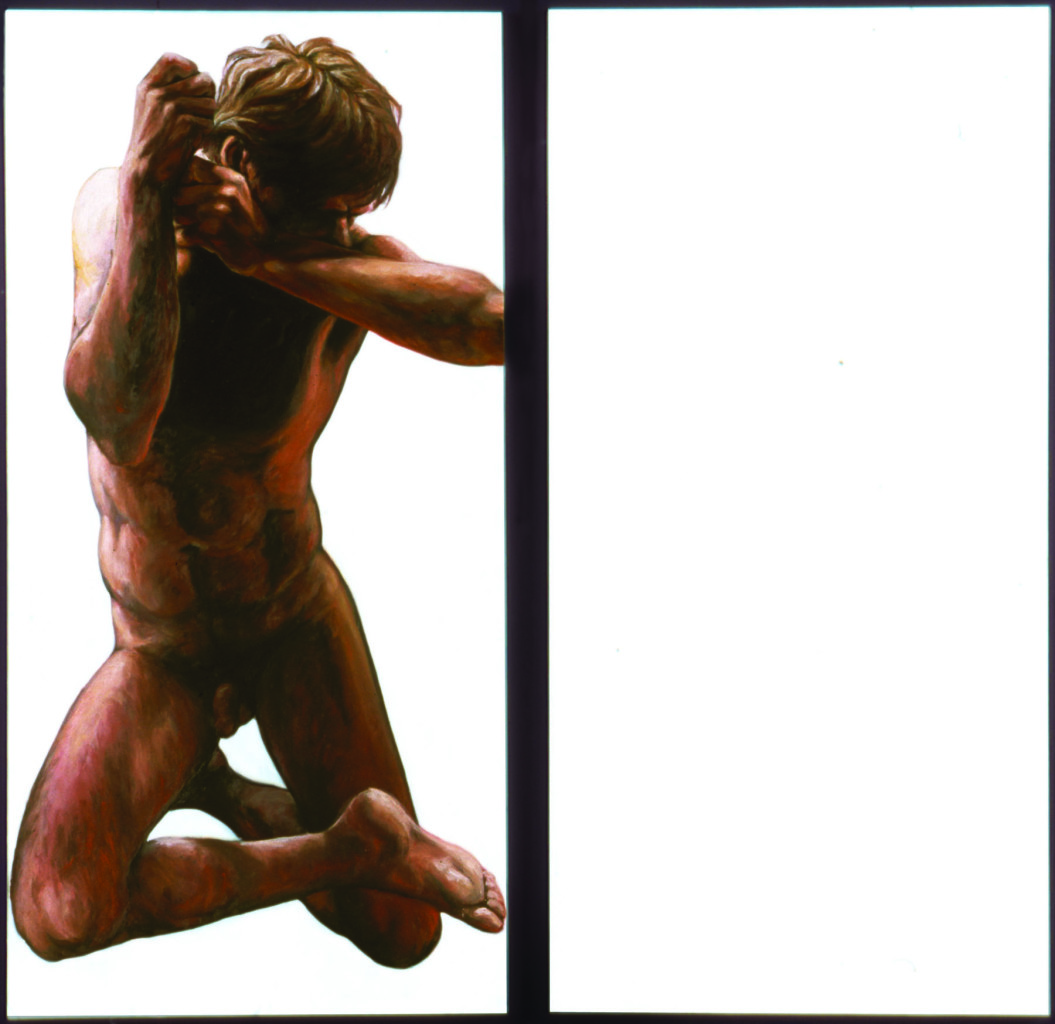

PLATE 1. Guy Kinnear. Saint George and His Quest, 2002. Diptych, oil on panel. 48 x 50 inches. Courtesy of Helmuth Aukes.

Not surprisingly, while he tried to find his own voice, Kinnear’s work showed the influence of his contemporaries. Saint George and His Quest, a composition in two zones from 2002, from the Spaces series, is inspired by the medieval folk tale of the Christian knight Saint George and his rescue of a king’s daughter who—decked out as a bride—was left as a sacrifice to a dragon [see Plate 1]. The struggling male figure against a pure white background resembles Longo’s Men in the Cities drawings in concept and format. But while Longo’s men wear business suits in their contorted throes of violence, Kinnear’s Saint George is classically nude. He is physically undergoing self-mastery, building himself up for the hero’s quest. The white void to the right suggests the unknown that the quester must face. For Kinnear, who believes that in order to be relevant, ancient sacred texts and myths must resonate with present issues, this Saint George symbolizes the masculine struggle to master anger in romantic relationships—another form of rescuing the bride, and heroism on the domestic front.

Kinnear never uses professional models in making his paintings. “The men who pose in my work are all from my immediate circle of friends and family,” he says. Before he begins a composition, “it is important that I know their stories, and that in dialogue we find connections between their lives as men and the traditional sacred and mythic narratives that were once a vital part of human culture.” The work of artist and model is thus collaborative and literary. In addition, Kinnear encourages his models to connect deeply with their physicality and “express what they feel and know about the narrative at hand through their movement, posture, and tension.”

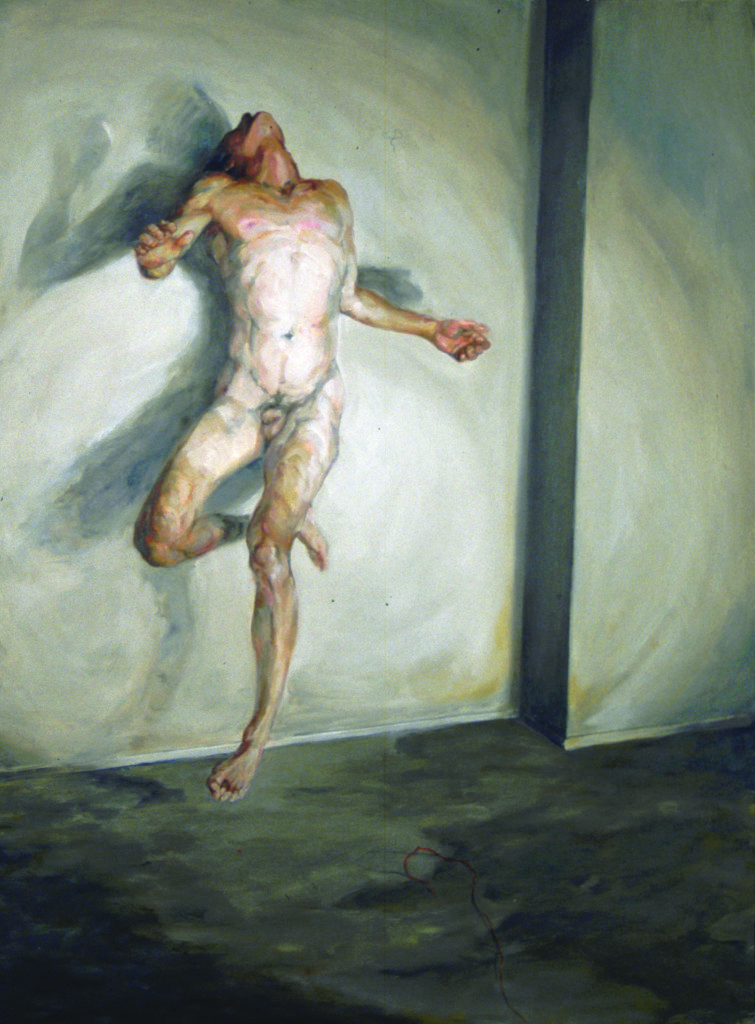

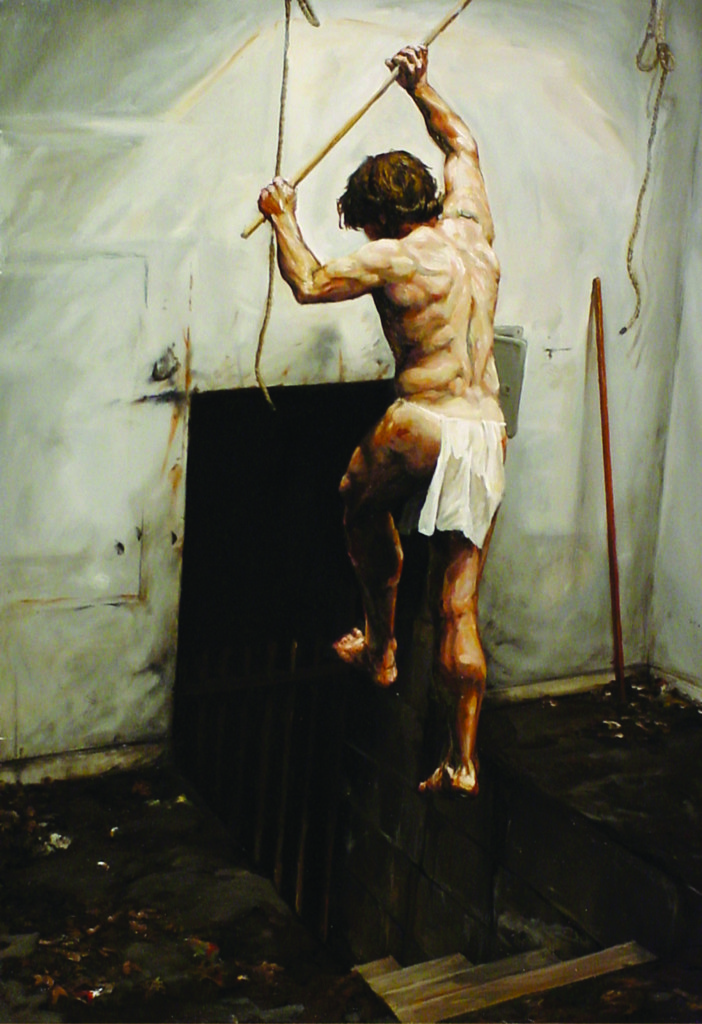

From 2002 to 2007, Kinnear moved on from the Spaces series to develop a new body of work called Rooms. In this series he encloses his figures in ashen-hued interiors. Significantly, the walls and floors do not anchor his male protagonists. The solitary figures often defy the laws of gravity and may float, hover, or ascend. The artist describes his approach as setting his “elements…in a context of modernist compositional elements as influenced by the camera.” In this regard, he joins numerous postmodern representational painters whose imagery is structured in part by the photographic lens or cinematic devices, Longo and Witkin, for example, as well as Gerhard Richter, Eric Fischl [see Image #39], and Tim Lowly [see Image #7]. As a result, Kinnear’s ambiguous gray rooms become the locale where contemporary male experience is metaphorically portrayed with surrealist-tinged visuals.

Gray Room 4 is such an image: a nude male suspended above the floor of an empty room [see Plate 2]. The athletic figure writhes and struggles as if trying to break free of some psychic turmoil. The drama is enhanced by the spotlight on his body, producing a shimmering leaden shadow on the wall behind him. Gray Room 6: Limbo is a more complex scene, featuring a basement entry cut into the wall of the room [see Plate 3]. In thin air, using a stick for balance, the figure negotiates an invisible set of stairs above the actual wooden stairs below him. It strikes me as a metaphor for transcendence in the face of a descent into bad options, calling to mind the faith that was asked of the apostles when caught on the dark, stormy Sea of Galilee.

Plate 3. Guy Kinnear. Gray Room 6: Limbo, 2007. Oil on panel. 36 x 25 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

During 2007 and 2008, Kinnear started another series, Ceilings, and produced eight paintings on this theme. (The entire series is on the artist’s website, www.GuyKinnear.com.) Ceilings are his metaphors for the constraints on authentic masculinity, which he believes is realized only through spiritual discipline. But Kinnear’s works are not mere postmodern illustrations of updated ancient spiritual practices. He recognizes that multiple historical, contemporary, and cultural influences shape the experience of males, and that the psychological and physical issues that men grapple with are complex and confusing.

PLATE 4. Guy Kinnear. The Fifth Ceiling: The Examination, 2007. Oil on panel. 36 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

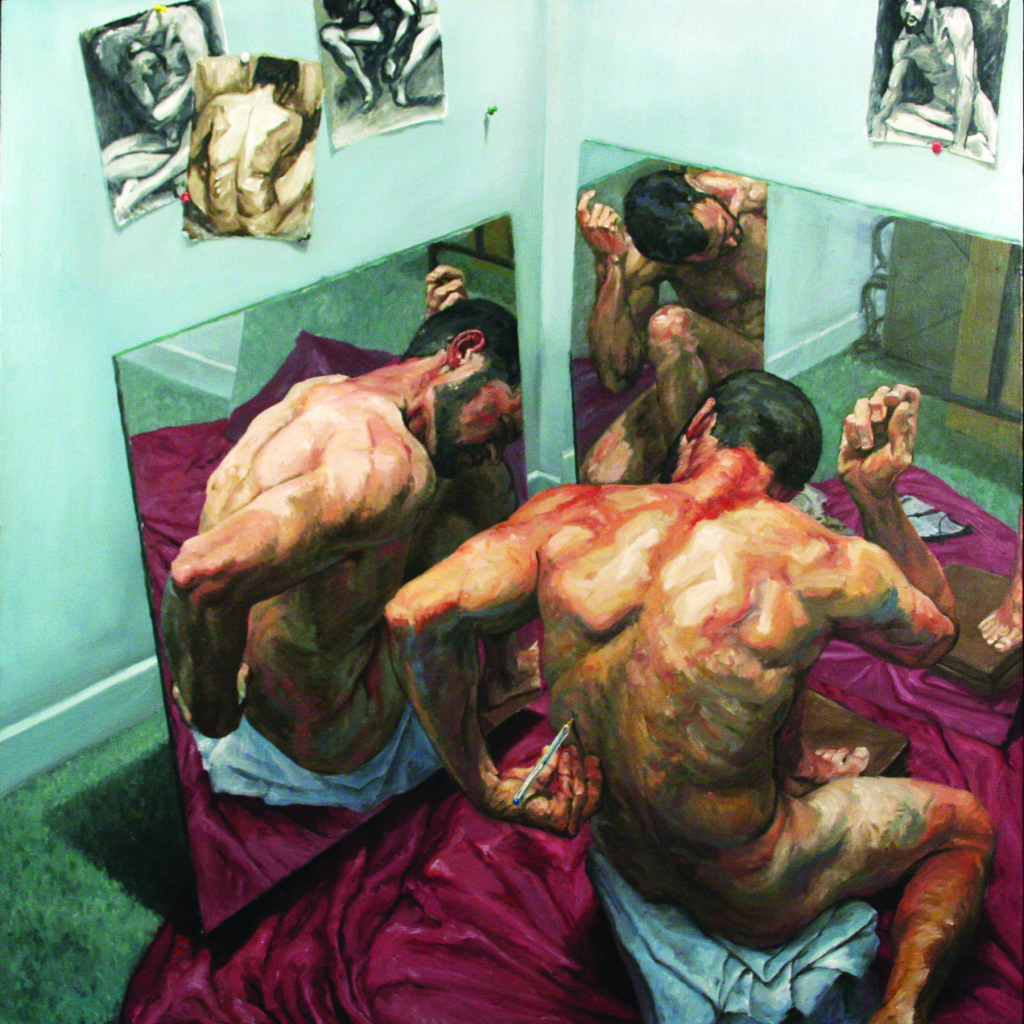

To depict this uneasy state, Kinnear used his familiar practice of drawing models in his studio, creating a visual metaphor for the pain a man must go through to reach self-knowledge and chart the way ahead. The Fifth Ceiling: The Examination offers a claustrophobic view that presses down on the model, who is posed in great torsion [see Plate 4]. He is literally cornered. The artist’s sketches tacked to the wall evoke the various images of masculinity that society holds up for men. Hemmed in by mirrors, the model experiences an infinite recession of his own image. Turning away from this confusing visual cacophony, he fingers what looks like a ball-point pen. Is he struggling to write a new narrative on his very body? (One recalls the oft-tattooed title character in Flannery O’Connor’s story “Parker’s Back,” who, desperate for redemptive purpose—and for God—finally commissions “a stern Byzantine Christ with all-demanding eyes” to be drawn upon his back. The tattoo artist replies, “That’ll cost you plenty.”) Some viewers have seen the stylus as a hypodermic needle plunged in the model’s back. Has he recognized that he must remove the “blade” from his life to achieve liberation? With careful, deliberate effort, he twists to extract this universal symbol of betrayal, addiction, and enslavement.

PLATE 5. Guy Kinnear. The Eighth Ceiling: The Diver, 2008. Oil on panel. 27 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the Bluebird Art House.

The Eighth Ceiling: The Diver is a departure from Kinnear’s stifling, closed-in spaces [see Plate 5]. A wide-open but off-kilter lakeside panorama beneath a summer sky is the locus for one man’s Evel Knievel–style vault across a chasm and into the depths. To the right, a diving tower seems to rear up, as if animated. We presume it was the launch point for the figure—a casually dressed, goateed, California-style guy, wearing his shirt open—who is more projectile than diver. This is no Olympic plunge with clean, splash-free vertical entry. The figure is in freefall, even at peace, folding his arms in acceptance. The Eighth Ceiling: The Diver seems to be about submission and trust, a radical metaphor for immersion into the Christian life via the sacrament of baptism—the springboard to new beginnings.

The main difference between Kinnear’s men and those of his older contemporaries is that Kinnear’s protagonists are searching for breakthroughs. Whether submitting or acting—or both—his men are on the journey to a redeemed masculinity, even in harrowing circumstances. As Kinnear explores this in his current Pater Noster series, he remains steadfast in his commitment “to continue my labor of finding visual bridges between the divergent realms of personal faith and public contemporary culture and the ways that identity is shaped in the tensions between the two.” As we discussed how this approach got worked out in his art, I recalled Susan Faludi’s concluding observations in Stiffed. To overcome their betrayal by societal forces, Faludi exhorted men to stop thinking of masculinity as a quality detached from their humanity: “The task of men is not, in the end, to figure out how to be masculine, rather, their masculinity lies in figuring out how to be human.”