IT WAS THE FIRST FULL DAY of the fall semester at the New York Academy of Art, and California artist Noah Buchanan was riding the Number 2 subway to lower Manhattan’s Tribeca district where he would disembark five blocks south of the school. The Brazilian beat of Paul Simon’s Rhythm of the Saints thrummed on his headphones. It was a cloudless late summer morning with temperatures expected to approach 80 degrees. Buchanan was beginning the final year of his MFA studies. Inspired by the school’s rigorous training in traditional drawing, he keenly anticipated the mentoring of Martha Erlebacher, Steven Assael, and Vincent Desiderio, three painters who had reinvigorated figurative painting in the last decade of the twentieth century.

Buchanan gathered up his drawing materials as he neared his Chambers Street stop. At the station the train suddenly shut off its engines. A voice on the MTA’s public address system boomed, “Ladies and gentlemen, due to an emergency, this train is out of service. There will be no further service today.” Ascending the stairway to street level, a perplexed Buchanan sensed an agitation in the crowds around him. As he looked down West Broadway and Chambers Streets, his gaze fell upon the monolithic silver skyscrapers of the World Trade Center, the twin towers. Both were aflame, emitting drifting clouds of gray smoke against the clear blue sky.

Despite his shock, Buchanan jostled his way to the site. Office debris and clouds of paper fluttered from the gaping, smoking hollows in the towers. Then he noticed another kind of falling object: people. Pressed by flames and acrid fumes, desperate office workers in the upper stories paused, then leaped a thousand feet to the streets below. Buchanan, whose career was shaped by careful study of the human figure, later recalled:

A large black form falls endlessly downward. It falls differently than the rest of the detritus in the air. It’s heavier, and it…plummets. Now I can make it out as a human body. This first figure I see falls the way a mannequin would fall: with complete lifelessness. “Oh my God!” The oath involuntarily escapes my throat, and I snap my head away. I’ve never seen somebody die in front of my own eyes. Nausea feels imminent, and I cover my mouth. Others are vomiting in the street.

[A] collective cry of dismay rises from the crowd as a large cluster of human bodies falls from the buildings. I can’t turn my eyes away this time. As the group falls, it breaks apart and it’s clear that some of them fall motionless, while others flail and struggle.

A short time later, Buchanan found a classmate: “A whole group of people just jumped together and they were all holding hands,” she despairingly told him. Around the base of the twin towers, the sound of jumpers hitting the pavement was indescribable. It is believed that two hundred office workers made this plunge their final act.

By mid-morning both towers had collapsed. Buchanan remembers walking back and forth between the academy and the World Trade Center, trying to be of some help as the grim day wore on. Eventually, covered with layers of gypsum and concrete ash that dusted surrounding streets and shrouded those who stayed in the area, he gave up and trudged a hundred blocks back to his apartment on the Upper West Side.

§

Within a month the New York Academy of Art reopened for classes. Faculty, staff, and students struggled to return to normalcy. Figurative artists, when their art becomes stalled, tend to return to drawing the human form, and this was Buchanan’s way forward. One of the life-drawing class models was a young American who showed an interest in Islam. He had Koranic exhortations tattooed on his wrists, and during breaks from posing he studied the Koran. He occasionally chatted with Buchanan. With his jihadi-style shaved head and sprouting beard, he seemed a man of inner conflicts. Anxious class members wondered about him. If he were a devout Muslim, why would he pose nude in front of men and women? Did he regard the art students as infidels?

His allusive portrayal of terrorist militancy empowered him to more deeply engage the trauma persisting after 9/11, driving him to find figurative narratives that could memorialize, convey hope, and affirm the value of life in the aftermath of three thousand fatalities. Eventually, Buchanan undertook two ambitious and provocative compositions, Resurrection and Jacob’s Ladder.

PLATE 6. Noah Buchanan. Jacob’s Ladder, 2002. Oil on linen. 68 x 54 inches. Collection of Frederica Wolfe.

The first to be completed was Jacob’s Ladder, an image from 2002 that served as a sort of requiem icon. His childhood knowledge of the Bible led him to adapt the story of Jacob’s sojourn in Haran from the twenty-eighth chapter of Genesis. Stopping at nightfall and “taking one of the stones of that place, [Jacob] made it his pillow and lay down where he was.” During his sleep, Jacob sees Yahweh and the heavenly realm in a theophanic dream wherein Yahweh promises him and his many descendants the “ground on which you are lying,” as well as God’s protection. When Jacob awakes, he exclaims: “Truly, Yahweh is in this place and I did not know!” He then takes the pillow-stone and sets it up “as a pillar…to be a house of God,” a memorial to his encounter with the holy.

In Buchanan’s painting, the male figure is nude, classically portrayed, and appears to slumber against a boulder, his back to the viewer [see Plate 6]. His posture also suggests mourning. In the distance a menacing, ashen-black cloud sweeps over the desolate landscape toward Jacob—yet the darkness is being overtaken by mysterious luminous wisps. In Buchanan’s iconography, areas of shadow and light are metaphors for the absence and presence of the divine. The emerging light—God piercing the dark—is a nod to the ladder from heaven that descended to earth in Jacob’s dream. Buchanan’s upwelling clouds recall the massive billows of ash that roared through the streets of lower Manhattan after the fall of the twin towers, but here the clouds of death are being superseded by strands of light, suggesting the prologue from John’s Gospel: “the light shines in the darkness, and darkness could not overpower it.” The glimmering metal basin in the foreground contains the anointing oil that Jacob poured on the rock pillar to commemorate God’s presence. Jacob’s stone becomes a memorial that will be anointed in mourning, claiming “this place” for the divine.

PLATE 10. Noah Buchanan. Resurrection, 2007. Oil on linen. 29 x 46 inches. Collection of D. R. Heiniger.

The first preparatory sketches for Resurrection were drawn in October and November 2001, but Jacob’s Ladder took precedence, and Buchanan shelved them for another time. After graduation he moved back to his home in Santa Cruz, where he had earlier received his BA in art from the University of California. Working through his 9/11 trauma, he finally completed Resurrection as in 2006.

The painting depicts two brightly illuminated male figures enveloped in blackness. A pale nude corpse lies on its side on a bed of white ash [see Plate 10]. Recalling the showering clouds from the fallen towers, the ash also alludes to the myth of the dying Phoenix that rises anew from its own ashes. Buchanan sees the recumbent figure as Lazarus, the friend whom Jesus resurrected in the eleventh chapter of John’s Gospel. Leaning tenderly over the dead man is a Christ figure. He presses the man’s chest, his mouth close to his ear, as if whispering Jesus’s words from the Gospel account: “Lazarus, come forth.” Almost imperceptibly, the dead man responds: his right hand is rosy with life, and he begins to raise his forefinger.

Resurrection is bold in its portrayal of the intimacy of life and death, and is a radical departure from the traditional iconography of this episode, where Christ stands apart from a shrouded Lazarus, summoning him from his tomb. Buchanan has said he was looking for a human interaction expressive of agape—divine, life-giving love—and the two-figure setting came to him from a desperate wish, shared by many, that someone—anyone—would be found alive in the ruins of the World Trade Center.

§

While he was completing Resurrection in California, Buchanan learned of a major art commission opportunity in La Crosse, Wisconsin. The art and architecture committee of the planned Roman Catholic Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe was reviewing artists’ portfolios. Serving as arts coordinator and advisor to the bishop was the veteran church artist Anthony Visco, who encouraged Buchanan to submit work. Ready for a new direction and a challenge, Buchanan applied, sending images of Resurrection and Jacob’s Ladder. He was candid that he was not a Catholic, had been raised as a Christian Scientist, and was “more spiritual than religious,” while sincerely offering his abilities to produce works that would support the devotion of visitors to the shrine.

PLATE 7. Noah Buchanan. Saint Faustina and Divine Mercy, 2008. Oil on linen. 132 x 54 inches. Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, La Crosse, Wisconsin.

Buchanan’s youthful forthrightness, his knowledge of baroque Catholic art, as well as his command of emotive figuration and formidable technical skills impressed the committee, especially the commissioning bishop, Raymond Burke, who was promoting a resurgence of Catholic sacred arts. Bishop Burke (now Cardinal) was and is one of the most powerful conservative voices in the American church, and the shrine church has an ambitious classical design inspired by Italian High Renaissance architecture, reflecting his traditionalist aspirations. Burke reserved final approval of the paintings that would adorn the church. With Visco’s recommendation, the committee commissioned Buchanan to produce two monumental canvases, each eleven feet high, depicting saints of the modern era: Maria Teresa Goretti (1890–1902) and Maria Faustina Kowalska (1905–1938).

Honored and awed at being awarded so major a commission, Buchanan looked to one of his artist heroes. “What would Caravaggio do?” became his rallying cry throughout the thirteen months he had to complete the two works. In the baroque era Caravaggio created an emotionally compelling, theatrical, and occasionally confrontational artistic style to portray Christian and Counter-Reformation themes. His compositions for the church frequently employ ordinary, non-idealized models who are robustly present to the viewer, and set in dark contemporary environments that use focused raking light on the dramatis personae, who are shown at the climax of the narrative. Some of Caravaggio’s subjects gape out of the canvas, compelling us to be present as witnesses.

Buchanan’s panel devoted to Saint Faustina portrays the Polish nun at her prayers, receiving one of her numerous visions of Jesus, who told her to proclaim that “mercy is the greatest attribute of God” [see Plate 7]. Faustina transcribed her visions and conversations with Jesus in a lengthy diary. In them he exhorts Christians to cultivate love and mercy so that they may “flow through one’s own heart towards those in need of it.” Faustina was elevated to sainthood in 2000 with the support of Pope John Paul II.

In one of Faustina’s visions from 1931, Jesus instructed her to sponsor a painting of his merciful attributes: “Paint an image according to the pattern you see, with the signature: ‘Jesus, I trust in You.’ I desire that this image be venerated, first in your chapel, and then throughout the world. I promise that the soul that will venerate this image will not perish.” An academic Polish painter was secured to fulfill this commission, and under the nun’s direction painted a white-gowned Jesus making a gesture of blessing. Translucent white and red rays (representing the water and blood that issued from his side at the final moments of his crucifixion) beam from his chest, manifestations of the divine mercy that she described in her diary. By any artistic standard, however, the Polish painting is conventional and tame, despite its visionary impetus.

PLATE 8. Noah Buchanan. Saint Maria Goretti with the Blessed Virgin Mary and Alessandro Serenelli, 2008. Oil on linen. 132 x 54 inches. Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, La Crosse, Wisconsin.

By contrast, Buchanan’s rendition of Faustina’s vision is richly narrative and dramatic, Carravagesque and classicist—the latter sensibility toning down baroque-era theatrics to better distill the nun’s interior vision. His tall, narrow composition unites heaven and earth in a hushed sacred moment. At the top, the hand of God extends from heaven as if commanding the vision of his son, touching the large halo, in which hovers the dove of the Holy Spirit. A drapery of pure white flows from God’s arm around the halo and down beneath the feet of Jesus, reaching the rapt Faustina, who has been meditating on the objects of Jesus’s passion. The red and white rays are more prominent in Buchanan’s painting than in the image Faustina directed. His is a post-sainthood image, a summa of six decades of the nun’s message of divine mercy as it has been embraced by the faithful and spread throughout the Catholic world.

Buchanan’s Jesus wears a tender and compassionate expression that—à la Caravaggio—is directed at the viewer, not the saint. The resurrected Christ is bare-chested, and the five crucifixion wounds are visible, drawing the viewer to his passion. Moreover, art-historically attuned viewers will recognize the graceful stance as derived from the Hellenist-Roman imperial statue of Augustus Caesar, who in triumphal general’s garb extends his arm to establish the Pax Romana—peace guaranteed by the might of Roman arms. This makes for an ironic comparison to Buchanan’s luminous Jesus, the Prince of Peace (in contrast to the imperial title princeps), whose self-sacrifice victoriously extends mercy to the world via the arms of love.

The second La Crosse panel depicts Maria Teresa Goretti, who may strike most moderns as a strange sort of saint. A poor and pious Italian peasant girl of nearly twelve, she was declared a martyr because she fought off a rape attempt, thus preserving her chastity. Enraged at her resistance, her assailant stabbed Goretti numerous times with an awl. She underwent five hours of surgery only to succumb to her wounds. Before she died, she prayed to the Virgin Mary and forgave her murderer, a troubled young man from a family with a history of madness and alcoholism.

Since her canonization in 1950, Goretti has been held up as a model of purity and chastity for American Catholic girls. Buchanan, however, was struck by the other part of the saint’s story: her forgiveness of her murderer, Alessandro Serenelli, and his subsequent repentance and asking forgiveness from her family, which he received. Upon release from prison, Serenelli became a lay brother of the Capuchin Friars until his death in 1970. Astonishingly, he attended Goretti’s canonization with her mother.

According to Buchanan, Bishop Burke and the committee anticipated a conventionally pious image of a demurely stoic prepubescent girl, hewing to traditional iconography. The artist—again asking himself what Caravaggio would do—instead imagined a scene similar to Saint Faustina’s: the heavenly realm extending light, grace, and forgiveness to earth. Buchanan submitted a study with three figures: the Virgin Mary, the child Goretti, and the jailed criminal Serenelli, shown at the moment of comprehending the girl’s forgiveness [see Plate 8]. His prominent appearance at the bottom of the composition initially stunned the committee, but after pondering the overall message, they were won over to Buchanan’s dramatization of ultimate reconciliation.

Hovering above an arid landscape, a beatific Virgin Mary serenely affirms the purity of heart of the sanctified peasant girl. Indeed, purity is in abundance: a dazzling corona of white lilies encircles the Holy Mother. Safe in her presence, the resurrected Goretti holds lilies in her hands, and turns from the Virgin, looking down tenderly to offer her flowers to the wretched Serenelli, enchained and cowering in the darkness of his cell. In prison, Serenelli had visions of the girl he murdered offering him lilies that burst into light in his hands and vanished. Buchanan depicts the climactic moment, the beginning of Serenelli’s repentance—a journey from darkness to the divine light of freedom.

Completing the two large paintings—including an unforeseen botching and correction of the pose of Jesus—in thirteen months to meet the dedication date of July 31, 2008, tested Buchanan’s endurance and proved emotionally exhausting. His spirits, however, were buoyed by the knowledge that the shrine would host numerous pilgrims and visitors; he saw his paintings of the intercessor saints as vehicles for people to “receive God’s attentions.” Not long after the dedication, Buchanan was moved to learn that relics of Saint Faustina were being donated to the shrine and a reliquary installed in the wall beneath his painting.

§

Noah Buchanan was born in 1976 and raised in Venice, California. He was an artistic prodigy in his youth and showed a predilection for realist and baroque art and an early desire for academic training. His parents recognized his talent and gave him books on the impressionists and modern art, but these had modest impact. It wasn’t until his mother gave him a book on Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), one of the masters of Spanish baroque painting, that serious interest was sparked. Buchanan recalls thumbing through this monograph and discovering Ribera’s Saint Jerome and the Angel. He was bowled over by the chiaroscuro image wherein a trumpet-blowing angel bursts from the heavens to command the terrified elderly church father to translate the Bible into Latin. Buchanan says his strong instinctive response to the encounter of the earthbound Jerome with the heavenly messenger came to make sense to him later, as he formed his own spirituality in life and art.

Buchanan’s family moved around the country and settled in Florida during his high school years. His art teacher saw his talent and pushed him to enter regional high school art competitions. Applying for college art programs, he was accepted at the Rhode Island School of Design, but the high cost of tuition caused him to choose the scholarship-endowed Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

With a temperament responsive to classical training, Buchanan thrived at PAFA, where he progressed from drawing basic geometric objects, classroom still lifes, and Greco-Roman plaster casts (bequeathed to the academy by Thomas Eakins), to sketching and finally painting the human figure. He also studied anatomy, mastering the names and functions of bones, tendons, and muscles. While Buchanan enjoyed his coursework, living in Philadelphia proved not to his liking, and he returned to Santa Cruz in 1996, enrolling in the UC Santa Cruz studio program and studying under the realist abstractionist painter Frank Galuszka, earning a bachelor of arts in 2000.

Galuszka’s mentoring was stimulating, but for Buchanan, like many figurative artists, deeper anatomical training was the key to mastery. It was Galuszka who encouraged Buchanan to study for an MFA under the “new classicist” painter Martha Mayer Erlebacher at the New York Academy of Art. Recognizing his need for focused study, Buchanan took his mentor’s advice and left for New York the summer he graduated. At the academy, Erlebacher persuaded him to explore the still life genre more seriously. His admiration of the Spanish baroque and the still lifes of artists like Francisco de Zurbarán helped him delve deeply into this genre, going beyond compositional aesthetics. Shortly thereafter, Buchanan incorporated still life into his own repertoire, as a multivalent vehicle for the imaging of psychological and spiritual states—metaphors on tabletops.

Noah Buchanan. The Magician, 2011. Oil on linen. 21 x 20 inches. Courtesy of John Peace Gallery, San Francisco.

Following his completion of the MFA at the New York Academy, the artist returned to Santa Cruz. He picked up numerous teaching positions on the central coast and in the San Francisco Bay area. Galleries in San Francisco and Philadelphia asked to represent his work. It was during this time that he also landed the commission for the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe. He painted the two massive panels at the Church of the Holy Cross in Santa Cruz. Thanks to enthusiastic support from the parish priest, Buchanan obtained a high-ceilinged, well-lit studio space on the second floor of the church’s old high school, with a view directly onto the bell tower. The artist fondly recalls the encouragement of parishioners who would look in on his progress over the year he labored on the panels.

In 2013, Buchanan relocated to southern California to teach life drawing at California State University, Long Beach, and to become a full-time professor of drawing and painting at the Los Angeles Academy of Figurative Art. The latter is the west coast equivalent of the New York Academy of Art and educates figurative fine artists and commercial artists for production work for Hollywood films. But when a promising personal relationship sadly ended, Buchanan returned to Santa Cruz in 2014.

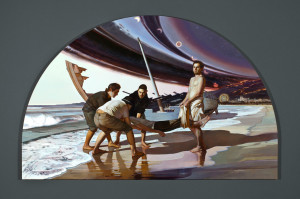

While in LA, he produced a major allegorical work that rivals his Wisconsin shrine paintings. A hemispherical composition, Entombment is staged on the beach with the Santa Monica boardwalk and pier in the distance, its Ferris wheel aglow in the twilight [see Plate 9]. The atmosphere is California oceanfront apocalyptic. In the distance, seasonally recurring autumnal fires consume the dry brush, blazing through the coastal mountains. Recalling Jacob’s Ladder, a sweeping shroud-like cloud of smoke arcs across the sky, while a complete solar eclipse waxes and wanes in time-lapse sequence. On the beach, four young men gently lift a body, apparently the victim of the wreck of the shattered boat behind them. The erect figure at right who looks out at the viewer is a self-portrait.

PLATE 9. Noah Buchanan. Entombment, 2013-14. Oil on panel. 36 x 57 inches. Courtesy of John Peace Gallery, San Francisco.

Critics of postmodernist thought, notably conservative critics, don’t like its open-endedness and elasticity. Postmodernist approaches resist resolution because they want to have it both—or even many—ways, keeping the options open. In such a system, where is meaning in philosophy, history, or works of art? As a late-middle-aged art historian, I have seen the earlier modernist certitudes of my discipline cracked open as new generations of scholars have discovered a richer fabric of meanings and crosscurrents in cultural epochs, styles, individual artists, and works of art. My own field of graduate study, the late-Roman and early-Christian era, has been overturned in the last fifty years, revealed as a fluid transitional period—indeed, on its own terms, a manifestation of late-antique postmodernism.

Our own transitional postmodernist era is witnessing the emergence of a neo-traditional art, including work earnestly dealing with spiritual, religious, and Christian themes—content that was severely policed until the 1980s. This has occurred within a skeptical climate, and has seen the surfacing of an element of our humanity suppressed for two hundred years: mystery. Many neo-traditionalist artists, however, are still struggling to project mystery—and, tempted by shortcuts, they appropriate the hieratic and naturalistic Christian art of the nineteenth century. This is bound to fail, as it often ends in nostalgia, anachronism, and didacticism.

In our day, reclaiming mystery within a neo-traditionalist approach may be best accomplished via minimal means, and it is by such means that Buchanan’s work succeeds. His first major paintings—Jacob’s Ladder and Resurrection—are pared-down narratives dramatically staged and given fresh contexts. They say more with less. Even the iconographic requirements of the La Crosse commission were reordered by his elemental classicized baroque style and emphasis upon the inner sanctity of the women, avoiding the florid emotions and narrative clutter typical of hagiographic works. Further, Memory of Grace and The Magician have in their mysterious simplicity musical counterparts in minimalist composers like Arvo Pärt, Veljo Tormis, and Ludovico Einaudi. And while Entombment is Buchanan’s most complex work to date, it is classically ordered by a compositional orchestration of a few broad planes, arcs, and spheres.

In a transitional period an art of genuine renewal often takes root with a novel simplicity. In an earlier age of religious regeneration and conflict, Caravaggio and his followers vividly portrayed ordinary humans encountering the divine in concrete terms. In our complex and pluralist era, Buchanan combines his observational skills, technical mastery, and essentialist imagery to introduce us to the beauty of the mystery we long for in our deepest selves.