Painters Frame Contemporary Painting

Painting has died and been resurrected several times in recent decades. Challenged by theory-laden conversations about art’s “post-medium” condition and a welter of deconstructionist propositions, painting seems nevertheless to have thrived in the face of adversity. Some would say it remains as manifold and imaginative as ever. In order to take its pulse, Image asked four painters to reflect on the work of any of their contemporaries who interest them. The four artists—Wayne Adams, Alfonse Borysewicz, Catherine Prescott, and Tim Rollins—are a diverse bunch. They paint in a variety of styles and differ in their level of engagement with art theory. Yet without prompting, all four suggested that they regard authenticity of statement as the most valuable—if not also the most elusive—quality in contemporary painting: They share a concern for the integrity of the painting as the arena where material meets meaning. Our thanks to James Romaine for organizing this symposium. The following is Catherine Prescott’s contribution.

Art is in a race with its interpretation.

______ —Fairfield Porter, Art in Its Own Terms

Plate 21. Kehinde Wiley. Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005. Oil on canvas. 108 x 108 inches. Copyright © 2005 Kehinde Wiley.

IN THE GRAND, elegant reception hall of the Brooklyn Museum of Art, a massive nineteenth-century building with a façade marked by Beaux-Arts decorative detail and a new entrance that, at night, reminds me of one half of a gigantic flying saucer attached to the front of the building, hangs a nine-foot square painting of a black man riding a bucking white horse [see Plate 21]. The horse’s mane and tail, and a golden drape around the man’s shoulders, are blowing as if in a violent wind as the two climb a dangerous rocky outcrop. Both are looking at us, the horse straining with a wild-eyed sideways glance, for he is about to slip, and the man with his head calmly turned down toward our position on the floor. The rider wears a camouflage suit and Timberlands. The background consists of a flat space covered with red and gold wallpaper, the sort of design that might be seen in damask, covering the wall of a grand Victorian dining room or perhaps a castle somewhere.

The pose of the figure and horse imitates Jacques-Louis David’s 1801 painting Bonaparte Crossing the Alps at Grand-Saint-Bernard. Indeed, the painting in Brooklyn is called Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, but even without the title and date (2005), and even if you had never seen the older work, you would know instantly that this is a skillful contemporary take on an old master portrait; and, if you knew anything about French history, you might be able to guess the original subject. You would also sense, without the benefit of art studies, that the painter knows something you don’t. Your instinct tells you something sly is going on here.

The painter is Kehinde Wiley, born in 1977. The museum’s wall text quotes him as saying, “Painting is about the world that we live in. Black men live in the world. My choice is to include them. This is my way of saying yes to us.” It goes on to explain: “Historically the role of portraiture has been not only to create a likeness but also to communicate ideas about the subject’s status, wealth, and power…. Wiley transforms the traditional equestrian portrait by substituting a young black man dressed in urban street gear for the figure of Napoleon. Wiley thereby confronts and critiques cultural traditions that do not acknowledge the experience of urban black culture….”

This explanation is a textbook definition of irony: there is discord and incongruity between the painting’s surface meaning and its underlying meaning. What we see first, the pose of animal and figure, temporarily convinces us that we are looking at something from an art history lecture, but the wallpaper assaults us almost simultaneously with a strong denial of that association. One by one we notice cues that this is about the present, yet here we are comparing this work to older paintings.

There is no doubt that Wiley intended all this. He has made an alluring fake. And the effect is to clarify for us that we have been left out of the picture. As we stand in the museum’s reception hall, we are literally beneath the painting. Apparently Mr. Wiley wants us to be corrected by what we see, to come to know what he already knows, something that we have been ignorant of. He is pedagogical. He assumes our position to be other than his. In one of the interviews on his extensive website, he says that he wants to make a place for himself in “all of this,” referring to the world of art and success. In another interview on YouTube, he tells us that “to be acceptable as a black man is probably the subject matter of this work in some way.” Even through the softening “probably” and “in some way,” we can see the single-mindedness of his painted codes and the direct hit on both the tradition of portraiture and the viewer who has accepted it as true history. His alluring fake is telling us we have been faked out.

Portraiture has come a long way in recent years. In November of 2006 I attended the annual Richardson symposium at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. The symposium, “Today’s Face: Perspectives on Contemporary Portraiture,” organized by associate curator Brandon B. Fortune was concurrent with the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, one of several shows celebrating the grand reopening of the museum after six years of renovation. The call for entries had been published widely in art journals several months before. Its tag line, “Let’s Face It: Portraiture is Back,” had the ring of a rising rebel cry, and hinted at the restoration of history itself. The appeal to portraitists, who were used to years of avant-garde art which didn’t have much place for them, and who may have hung onto the tradition of portraiture like a dog with a rag, was one of solidarity, a knowing brotherhood. It elicited a response from four thousand of them.

The symposium consisted of morning lectures by two art historians and a museum director about current aspects of portraiture. Even the notion that there might be more than one aspect was somewhat radical. In the afternoon were live interviews with three portrait artists, including power-point presentations of their work. Two had pieces in the competition. The third was Kehinde Wiley. He was forthcoming about his ideas. He had, as a Yale MFA candidate, seen portraiture as absolutely faux and been interested in deconstructing it. But at the Studio Museum of Harlem he developed a romantic idea of portraiture as pointing to something bigger. He wanted to work with portraiture as a sign and with painting as authority. And he wanted to “ham it up.” When the interviewer pushed him about the deliberate inauthenticity in his work, his voice took on a wistful quality. He wished he could make something that was not ironic, he said: “There’s a certain sadness…. We all wish for those soft, cuddly moments of authenticity, but we can’t do that.” I wanted to jump up out of my seat, wave my arms, and yell, “Yes, you can, Kehinde! You can do anything you want!” With all his self-described tricks, his skill, his business acumen (“Part of what I’m trying to do is imbibe the corporate model,” he says; and, “I create high-priced luxury items for wealthy clients”), and his academic theory, he seems trapped by his success, by how he got there, and by how he will continue to develop his career. And he seems trapped by irony.

Artists are generally full of self-doubt. We prefer to think of ourselves as being on our own track, yet no one is immune to trends and changes in the art world. Everyone asks the question, “Where does my work fit in?” I had a gifted painting student at Messiah College who transferred after his sophomore year to a BFA program. From there he aimed to go to Yale for his MFA, a top choice for any ambitious artist. After applying and being rejected, he told me that although he would never go far from painting the figure, he had decided to paint it ironically, at least until he was accepted at Yale. “After that,” he said, “I can do anything I want.”

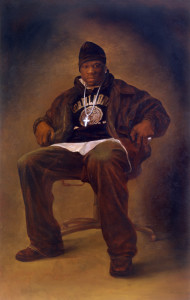

Irony in painting is nothing new. Even in portraiture it has been around a long time: think of Goya’s nineteenth-century portrayals of the Spanish royals as morons. Last summer’s controversy over the July 21 New Yorker cover showing the Obamas as flag-burning Muslim terrorists bumping fists in the Oval Office brought irony in art to the op-ed pages. The question that editor David Remnick addressed in response to objections was not whether or not the Obamas are really like that, but whether or not the readership of the magazine, and the larger public, are capable enough, smart enough, to understand that the depiction of said lie exaggerates its absurdity. By the time my copy was delivered to rural Pennsylvania the controversy was over, but the picture on page 16 of Kehinde Wiley sitting in front of one of his portraits was a real surprise. The exhibition that had attracted such coveted attention was Wiley’s solo show of portraits of rappers at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Safe to say, Mr. Wiley has made a splash in the art world, a very unusual position for a portrait painter.

Wiley is not the only artist who has painted rappers in recent years. In March, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit exhibited Holy Hip-Hop! New Paintings by Alex Melamid. If the name rings a bell, it’s because he and Vitaly Komar were a famous Russian conceptual art duo for nearly four decades. The declared intent of their early work, beginning in the 1970s, was to examine social realism, but the irony of the paintings was so obvious that the two were branded as political dissidents. As they progressed in irony, they delighted the international (and commercial) art world in 1995 by adding a third partner, Renée, an elephant they met in the Toledo zoo, with whom they collaborated on abstract paintings. As Mr. Komar put it, “The elephant’s trunk is amazing…dexterous and sensitive. And, of course, elephants are extremely intelligent, so Renée had a really very impressive command of the brush.” They proceeded to establish several elephant academies in Thailand where, Mr. Melamid said, “We gave them an opportunity to have a second career, to become artists.” They later developed two other imaginary (literally invented) artists, and also brought a dog and a chimpanzee to the (s)table.

Plate 23. Alexander Melamid. 50 Cent, 2005. Oil on canvas. 82 x 52 inches.

What is Alexander Melamid doing painting over-lifesize, dramatic, skillful likenesses of Snoop Dog and 50 Cent in a style that Carol Kino describes as recalling the court paintings of Velasquez [see Plate 23]? “I am repenting for my sins; I am a born-again artist,” he told Ms. Kino in an interview for the New York Times. These aren’t his first portraits. He and Mr. Komar did a series of ironic portraits (read kitschy in this case) of Stalin, Lenin, and George Washington after emigrating to the US in 1977. But the rappers are not ironic. The works bear the hallmarks of traditional portraiture: likeness, naturalism, evidence of training, and culturally significant subjects. Nor is this new venture into portraiture a flash in the pan. He’s currently painting monumental portraits of cardinals, priests, and nuns for an April 2009 exhibition in London and is planning a portrait series of contemporary Russian captains of industry. Where did this come from, and why now?

Melamid and Komar were born during World War II in Moscow, and were trained to produce social realist art in the official Soviet manner. The key word here is “trained.” For although they rebelled, joining the dissident underground, and later were expelled from the Moscow Union of Artists in 1974, they had developed traditional skills. The denial and rejection of those skills for nearly forty years has an obvious connection with choosing animals for painting partners. As Mr. Melamid put it, “Then, I wanted to paint as bad as possible. Now, I make as good as possible.” He calls his early paintings “horrible” and goes on to say, “My partner and myself, we were very ironic about art, but at a certain point, I realize that I just cannot go this way because it is totally ridiculous, the art itself. I lost my faith.” Apparently he had lost faith in the very world in which Kehinde Wiley wants to make a place for himself. With these new portraits, and what Kino calls his “sudden embrace of serious painting,” Melamid returns to a childhood conviction that painting is “a sacred and amazing thing.”

Plate 22. Jacob Collins. Self-Portrait (In Studio), 1992-94. Oil on canvas. 50 x 62 inches.

If an embrace of serious painting—painting that believes it might be sacred and amazing—has any place in contemporary art, then the current classical realist movement has staked out a large claim in that territory. Painter and teacher Jacob Collins is, if not the actual founder, the most prominent representative of the goals and ideals of the classical realists. His recent exhibit Rediscovering the American Landscape at Hirschl & Adler Modern was a tour de force of representational virtuosity and sincere love of nineteenth-century academic painting. The classical realists have taken on the task of training rapidly increasing numbers of students in their academies and ateliers to draw, paint, and sculpt traditional subject matter in the skillful and refined manner that was lost to art schools during the twentieth-century. Collins’ straightforward depiction of himself in the studio exemplifies many of the techniques that classical realists value and teach [see Plate 22]: the consistent use of light, which illuminates small details as well as larger forms to create a believable naturalism; the absence of intense colors or crisp edges that might stop the eye and get in the way of an illusion of atmosphere, or air; the layering of objects from front to back to make a deep space; and the extensive variation and repetition of hues within a very neutral palette, which unifies that space. One might guess that a movement which proposes to leap backward over modern art, land in the nineteenth-century, and pick up painting where it left off (and eventually ran its course and died) would not claim “freedom,” that battle cry of the American avant-garde, as one of its tenets. But freedom is exactly where these artists stand their ground.

I sat next to Mr. Collins at a luncheon hosted by the Newington-Cropsey Cultural Studies Center which publishes the American Arts Quarterly, and whose purpose is to “promote values inherent in the nineteenth-century works of the Hudson River School painters.” When Mr. Collins tossed out to the table a strongly worded comment about the superiority of an academic approach to painting over what he considered the indoctrination of modern art ideals, I took the bait. Although I know very well that originality was an unhelpful trap in modern painting, I found myself saying, “But surely you have to be careful not to move into imitation.” He shot me a look and said, “I can do anything I want. Who is to say I can’t imitate?” His question raises the problem of thinking of imitation as the opposite of originality.

When I first encountered the classical realists I thought that their paintings were ironic. One can’t help but compare them to earlier works; at first, one suspects some hidden commentary afoot, as in Wiley’s equestrian portraits. But this work, though imitative, lacks discord between its surface and underlying meaning. These painters are not trying to tell us something we don’t know. For many in their audience, traditional painting is a relief.

At the other end of the table from where Collins and I discussed which of us was more brainwashed sat the distinguished art historian and philosopher Donald Kuspit. A prolific and widely published author, Mr. Kuspit has been highly respected in contemporary art criticism for decades. Early on, his writing for Artforum and other conceptually oriented journals which eschewed traditional artistic values was sympathetic to the avant-garde. One might ask what he was doing at a Newington-Cropsey luncheon. If ever a man has changed his way of thinking, Mr. Kuspit is he. At a dinner in February honoring him as the recipient of the tenth annual Newington-Cropsey Foundation Award for Excellence in the Arts, Mr. Kuspit stated that he shares the foundation’s purpose of “re-enlisting art in the service of humanistic transcendence.” He was asked to speak on the current state of the visual arts, and began with this statement: “Avant-gardism has exhausted itself, however many interesting works it may continue to produce. I think this has to do with the fact that it never had a firm foundation in tradition, and thus remained inwardly precarious and insecure.” He believes that originality is not possible without tradition as a basis, and that what has happened to the avant-garde has been a process of trivialization, making trends and novelty take the place of originality. He cited the aesthetician Theodor Adorno who wrote (in Kuspit’s paraphrase) that the avant-garde has become “an instrument of mass entertainment rather than of psychological insight.”

The painter and film director Julian Schnabel is able to engage both these notions of art—instrument of mass entertainment and instrument of psychological insight—though not in the same medium. As a painter, the neo-expressionist of the 1980s who was known for attaching broken plates (inspired by his brief career as a New York dishwasher) to his massive canvases and then painting over them, has done a fascinating job appropriating (as opposed to imitating) what critics called an “old master style.”

Schnabel is known for his ability to keep one step ahead of art world trends. His 1997 exhibition Portrait Paintings at PaceWildenstein consisted of twelve oil portraits on nine-foot canvases in which decidedly and deliberately badly painted figures dressed in eighteenth and nineteenth-century costumes floated on a non-representational ground. In case we were not sure the portraits were ironic, several had expansive blobs of white paint dripping down, or splashing up, across the figure and the space behind. The canvases were framed in pinkish, putty-colored cast rubber that at first glance imitated the wide, elaborate molding of old master frames. The catalogue is bound in wine-red velour.

Julian Schnabel also directed the gorgeous, acclaimed 2007 film The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, a film that almost seems to have been made by a different person. I was stunned not only by its quality, but by its themes of interiority, human connection, and the inspiration of thoroughness—three qualities that could never describe the last twenty-five years of Schnabel’s painting. The film is based on the memoir of Jean-Dominique Bauby, who after a massive stroke was completely paralyzed except for one eye. Mentally undamaged and fully alert, Bauby developed a way of communicating by blinking, which he used to write his book. The film is not sentimental, nor does it bare its realism in the guise of toughness. Rather, it walks the line between the true mess of being human and the transcendent humanism of our love and longing. The art of Schnabel’s film was in giving us enough detail on both sides of that line to lead us into a deep connection with Bauby in all of his, and our, complexity.

The ever-savvy Schnabel is sticking with irony in his current series of badly painted commissioned portraits—including those of the lucky winners of a recent MasterCard “priceless” campaign that ran in the New Yorker. Does film allow him to move on to a kind of art that he knows won’t fly in painting at this point?

I agree with the art historian Garrett Stewart that the crisis of painting in modern art is related to a crisis of interiority, and I believe that interiority is a necessary component of human connection. What I like best about nineteenth-century writers like Thomas Hardy and Edith Wharton is not their style of writing or the style of life they describe, but their insight into human character, both its beauty and its flaws, as reflected in their interior life. I believe that Facebook, MySpace, and the general social networking frenzy are a manifestation of the slow drain of that insight. What I like best about twentieth-century painters like Picasso and Cezanne is not the style in which they paint, or the supposed originality and freedom of their work, but the direct connection and struggle they had with their subject matter, messy as that was, because they insisted on starting with their own convictions. As Kuspit puts it, I am looking for art in the service of human transcendence.

I suspect that portrait painting is a microcosm of painting in general, and that the current duality between serious and ironic painting is really a duel over whether, as Donald Kuspit said and Alexander Melamid dreamed, art in the service of human transcendence is valuable or not; and if it is, how does one keep it from being cheesy; and if it isn’t, how does one keep it from being a regrettable absence. I believe that the traditionalists, by starting where previous artists have finished, run the danger of making their subjects too perfect to connect with, and that the ironists risk separation by using their subjects to make themselves superior. Both are underestimating themselves.

Catherine Prescott taught painting at Messiah College for twenty years and continues to teach with Gordon College’s Orvieto Program and Andreeva Portrait Academy. She was awarded a 2008 Individual Artist’s Fellowship from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts. Her work can be seen at www.PrescottPaintings.com.