Painters Frame Contemporary Painting

Painting has died and been resurrected several times in recent decades. Challenged by theory-laden conversations about art’s “post-medium” condition and a welter of deconstructionist propositions, painting seems nevertheless to have thrived in the face of adversity. Some would say it remains as manifold and imaginative as ever. In order to take its pulse, Image asked four painters to reflect on the work of any of their contemporaries who interest them. The four artists—Wayne Adams, Alfonse Borysewicz, Catherine Prescott, and Tim Rollins—are a diverse bunch. They paint in a variety of styles and differ in their level of engagement with art theory. Yet without prompting, all four suggested that they regard authenticity of statement as the most valuable—if not also the most elusive—quality in contemporary painting: They share a concern for the integrity of the painting as the arena where material meets meaning. Our thanks to James Romaine for organizing this symposium. The following is Alfonse Borysewicz’s contribution.

LAST YEAR in Dublin I was fortunate enough to hear the poet Aidan Matthews speak on a panel on spirituality and the arts. In a profuse sweat, he told us about his bipolar life and these lost modern times (wonderfully recalled in his book According to the Small Hours). What I remember most was his warning against the “idolatry of our own narratives.” Through his Catholic faith, he had come to believe that God will fill in our narratives for us. Hearing this was a great liberation for me. In the art world, there is a constant pressure to frame oneself—on résumés, in blurbs, and at dinner-party talk. Worse, we often come to believe—personally and collectively—in these narratives. We want to control the flow of the story and define the ending before its end—and even Aristotle recognized the foolishness of such thinking. But God is the undertow. As the theologian Bernard Lonergan observed: “Just as man does not live on bread alone, so knowledge does not serve on certitude alone.”

I once wrote an extensive narrative of myself in these pages [see Image issue 32]. Looking back, I now realize what was missing: the abandonment of certitude, the willingness to give up on making sense of it all, and the honesty to admit it. When we let go of our certitude, as Samuel Beckett puts it, something happens. In a roundabout way, this has been the story of my own painting over the past ten years. I have walked away from a market-obsessed art world and recommitted myself to what God has offered me: a saeculum. One human lifetime. A time to live, a time to believe, a time to hope, and a time to reconcile. I have thrown my lot in with the community of saints and sinners. I have solidarity with the church and gratitude for the gift of life. Like many wounded moderns, I breathe the air of the present with an increasing sense of indebtedness.

Several artists have recently helped me release my certitude. By focusing on someone else’s hand and voice for a change, I’ve been able to give up trying to control the flow of my own story and allow something to happen in my being. Oddly, though I have been obsessed with the Christian praxis in my own work, there’s little direct engagement with Christianity among them (with one exception). Yet there is a common thread. We are all searching for an anchor that checks what John Lukacs calls the shallow, ephemeral, and near-fanatical spirituality of our times. These artists all avoid the guise of revolutionary genius that plagues our contemporaries. Rather, their genius is in their ordinariness.

Plate 16. Tadhg McSweeney. Helicopter, 2004. Oil on board. 8 x 10 inches.

I met Tadhg McSweeney last year in Dublin, and was able to visit his delightful and cluttered studio at Red Stables, where he was doing a residency. His small canvases seem to swim against the current. His warm, intimate palette is interrupted by familiar and menacing objects, as in Helicopter [see Plate 16]. Something is just not right in his paintings, and all these months later I’m still wondering what it is. There is a Paradise Lost element that seems to echo Ireland’s recent tremendous social, religious, and economic changes. Another work, Picnic, depicts a bear on his toes taking stock of an interior space. It looks to me like the bear of globalization peering in on the unsuspecting household of Ireland itself.

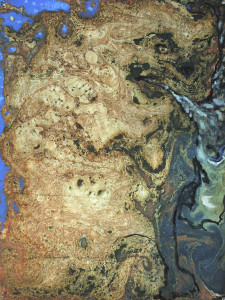

Plate 17. Matthew Poindexter. Hell, 2006. Oil and enamel on paper. 22 ½ x 16 inches.

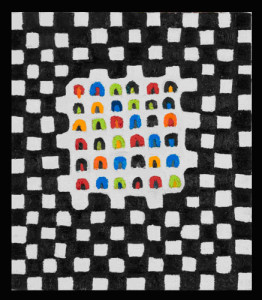

Matt Poindexter and Elisa Soliven, both young painters, are a couple. Each has a distinct vision, but they share a humility of approach as well as an innocence and excitement in their gushes of color and form. We tend to think of art as a solitary struggle, so it’s interesting to consider a case like this. When does one vision recede, the other expand? When do they merge? Poindexter works by floating oil paint on top of a pool of water like an ancient bath. The floating paint swirls, waiting for a sheet of paper to be laid over it to absorb the paint and capture the forms—waiting for something to happen. The finished work looks both archeological and modern, and seems to tease us with how ordinary we still are. Hell depicts not a Dantean circle of fire but one of those muddy pits we all played in once [see Plate 17]. This one is filled with some sort of biological hazard, and we kneel over it, stirring its multicolored chemicals. Soliven calms us down with works like Labryrinth and Checkers [see Plate 18], paintings that bring us back to the everyday, to living now instead of being consumed with lust for certainty about tomorrow. We are allowed to play, to be, to partake in something happening.

Plate 18. Elisa Soliven. Checkers, 2006. Oil on canvas. 16 x 14 inches.

I like to imagine the painter Thomas Hardin sitting down for dinner with Samuel Johnson and John Henry Newman. An anglophile Texan, Hardin is a great conversationalist and a great mind, and could easily write a dictionary of his own. Now working in London, he is gifted in theology and the arts, and unlike the other three painters I’ve mentioned, he shares my obsession with Christianity. He is now working in design and architecture, but his true roots are in the church and the fine arts. From needlepoint to sculptural installations for liturgical celebrations to drawing, weaving, painting, and even ringing of bells, Thomas lives and breathes creative sacred space. His work also faces the present tensions in the Anglican Church between traditionalists and liberals. His Stations of the Cross make faith paramount, transcending our fixation with cultural and gender issues. Combining embroidery with pencil, canvas, paint, and more, they echo the grand tradition of all the faithful that—we often forget—makes us a community [see Plate 19]. Hardin’s delicacy and nuance is modern yet medieval, echoing those great cathedrals of our faith.

Plate 19. Thomas Hardin. Station XI: Jesus Is Nailed to the Cross, 2006. Intaglio on linen with hand embroidery, edition of three. 19 ½ x 22 ½ inches.

This spring in downtown Brooklyn I happened to eat my lunch in a grove of trees at the MetroTech Center. I was quickly mesmerized by what I saw in the branches overhead: organic nests of plastic bottles filled with watermelon-colored water and tied in clusters [see Plate 20]. This was installation art with a painting sensibility at its best. The arrangement used the trees and sky to frame our perspectives from below. I had a hunch about who the artist was, and soon found a plaque naming Tony Feher (the installation was sponsored by the Public Art Fund). Feher, who refers to his works as “tricks,” uses common, functional materials such as plastic bottles, light bulbs, and thumbtacks—all the artifacts of our disposable culture. He carefully chooses his material for its color, shape, and texture to draw our attention as he integrates the work into the landscape. Watermelon was the perfect color for the interior of this grove, which stands within one of Brooklyn’s priority security centers, where emergency fire and communication stations are cordoned off from the beautiful public space by ugly concrete barriers. The air is thick with a sense of waiting. In downtown Brooklyn, the calm and silent grove of jeweled trees stands on unsettled, even dangerous ground, a metaphor for our times. The coexistence of beauty and menace prompted me to utter the same prayer the disciples prayed at Emmaus: “Stay with us, Lord.”

Plate 20. Tony Feher. A Little Bird Told Me, 2007. Cotton mason’s line, plastic beverage bottles with caps, water, and liquid water color. Dimensions vary. Commissioned for Everyday Eden, organized by the Public Art Fund at MetroTech Center in Brooklyn. Courtesy of the artist, D’Amelio Terras, and PaceWildenstein. Photo: Seong Kwon, courtesy of the Public Art Fund.

Not until the tenth chapter of his Confessions, after pages of personal reflection, does Saint Augustine begin to question how much he can really know himself: Quaestio mihi factus sum (I have become a question to myself), he writes. So I have hinted here. Through circumstance I came across these five artists, and through their hands I glimpsed epiphanies both ordinary and profound. Something happened when I saw their work: I was pulled out of my own story and into theirs, and I saw myself anew. They are good neighbors.

Alfonse Borysewicz received a master’s degree in theology before studying painting at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. He has received a Guggenheim Painting Fellowship and has had solo shows at Richard Anderson Fine Art, Yoshii Gallery in New York and Tokyo, and Francine Seders. He lives and works in Brooklyn.