ON MAY 16 of this year, Night Sky #2 by Vija Celmins, on view at the 2008 Carnegie International at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art, was vandalized by one of the museum’s own security guards, who used a key to cut a gouge down the painting’s middle, damaging it beyond repair. While this act was universally condemned in art-world news sources, the disclosure that the painting was estimated to be worth $1.2 million sparked a small storm of public debate about Night Sky #2’s purpose and value. One blogger even lobbied the old “a child could have made this” criticism, a salvo regularly aimed at abstract and conceptual art. While the suggestion that many artists, much less children, could rival Celmins’s exacting photorealism is dubious, and there is no point in parsing the motivation of a vandal who has already begun to mount a “mental stress” defense, these attacks on Night Sky #2 raise questions about the assumptions we bring to contemporary painting. While Celmins’s paintings of domestic appliances, seascapes, and spider webs visually engage even viewers unfamiliar or uncomfortable with more obviously conceptual art, Night Sky #2 suggests that representational painting can be a medium of perceptual experience. Celmins’s work challenges the conception of a painting as a picture to be looked at (what is sometimes called pictorialism) and proposes a method of painting that examines how the eye sees and the mind processes visual information—issues critical to our spiritual survival in an increasingly virtual and digital era.

As Celmins’s oeuvre has evolved over almost five decades, her work has been a series of careful and strategic responses to two challenges facing contemporary painting: the increasing, almost ubiquitous, presence of mechanically produced imagery (from photography to television to digital media) and the legacy of Jackson Pollock.

When Vija Celmins (pronounced vee-ya seel-mins) attended art school in the early 1960s, first in Indianapolis and then Los Angeles, there was a sense that abstract expressionism, along with modernism, had exhausted itself, but there was no clear sense of a new direction in which painting should go. Although many of the methodological challenges to the concept of art and the practice of painting from the likes of Pollock and Willem de Kooning continued to impress themselves on artists of Celmins’s generation, abstract expressionism itself had become a self-recycling style increasingly removed from the dialectic exchange with contemporary experience that had given it birth.

At this critical moment in her oeuvre, and perhaps in the history of painting, Celmins made a break from her abstract work with a series of still lifes, all painted in 1964, that present solitary domestic appliances against almost monochromatic backgrounds, as if these objects had fallen into abstract paintings. Pan depicts an electric frying pan at what Celmins claims is life size [see Plate 1]; however, our ability to measure the pan’s scale is impeded by the object’s placement in a void and by the odd angle of our vantage point, not quite straight on and not quite over head. The pan is marooned in space; only its electrical cord tethers it to the world beyond the frame, a sort of umbilical cord that sustains our belief in the work’s realism.

Overall, Pan is painted energetically, particularly when compared to Night Sky #2. Even in reproduction, Celmins’s brushstrokes provide a distinctly personal touch to a representation of an otherwise anonymous object. Here the pictorial subject (this is a pan) and the literal surface (this is a painting of a pan) are held in equilibrium, especially in the way Celmins treats the steam that rises from the lid. This haze creates a slippage between the object being pictured and the abstract background, visually unifying the painting by integrating the pan and the means of its representation.

Because her subject matter has sometimes been drawn from the world of everyday commercial objects, Celmins has been described as a Pop artist, a reading that stems more from a desire to fit her paintings into a ready-made narrative than to examine them on their own terms. Like classic works of early Pop Art, such as Andy Warhol’s soup cans and Roy Lichtenstein’s painting of a tire, Pan shows us a commercial object that we use but don’t really look at. But Pop Art was more than its subject matter; it was also concerned with applying the techniques (such as silkscreen) and visual strategies (such as repetition and glamorization) of mass media in the realm of art. By contrast, Pan belongs to a history of trompe-l’oeil easel-scale painting that not only departs from abstract expressionism but that was largely ignored throughout the twentieth century.

The trompe-l’oeil tradition emphasizes the artist’s ability to beguile the eye. Pan baits our appetite with pictorialist promises, inviting us to imagine what’s inside, but the lid is closed and we are denied access. Celmins seems to be suggesting that our paradigm of looking at Pan as an elevated form of illustration is misguided and she will not reward it. Instead her paintings strategically use our pictorial presuppositions against us in order to generate more complex experiences. Pan’s depiction of its subject matter according to pictorial principles in a space that has no sense of dimension or apparent boundaries generates a picture-perception dialectic that has become increasingly central to Celmins’s art. In the context of her ongoing project to develop new methods of seeing and making seen, Celmins’s abandonment of abstraction, then the fashionable strategy of painting, may have been a strategic move to explore possibilities of representation that let her critique the state of contemporary painting.

Some art critics, such as the New York Times’ Roberta Smith, have noted that these appliance paintings coincide with Celmins’s first extended period of separation from her family and have interpreted the solitary objects as “surrogates for her own isolation,” stand-ins for a young woman away from home and competing in the still male-dominated arena of painting. Not all of her still lifes have gender-specific associations, however. Hot Plate depicts an object as likely to be found in a bachelor’s apartment [see Plate 2]. If Celmins’s gender plays a role in these still lifes, perhaps it is that, in contrast to the heroic and grandiose canon of abstract expressionism, these works are modest, understated, and unassuming. Celmins herself downplays any personal or iconographic significance to her subject matter, then and now. These were simply things in her studio, she says.

Pan and Hot Plate’s subtle and oblique response to the work of Jackson Pollock may be the strongest and most interesting of any work of fourth-generation abstract expressionism. Pollock’s technique of pouring paint on canvases laid on the floor was born of his objective of eliminating the distance between himself and his painting. The results were a revolutionary challenge with which painting is still contending.

Pan and Hot Plate, unlike later works like Night Sky #12 and Web, share few visual similarities to Pollock’s “all-over” and “action” paintings. Nevertheless, Celmins’s still lifes of 1964 may represent a careful conceptualization of her post-Pollock project. Much of the writing on abstract expressionism, some of it by the artists themselves, describes it in Promethean or alchemical terms. Pollock called his own work “energy and motion made visible.” Paintings like Galaxy, Sea Change, Alchemy, and Autumn Rhythm, in their structure and rigor, subtlety and monumentality, effect a metamorphosis of matter. They read like cosmic electrical storms in which the friction of material and form sparks a currency or charge that races through the painting.

Celmins’s appliances—a lamp, hot plate, heater, fan, and television—are also electrical, a fact she highlights in every case by including a cord running from the object to the painting’s edge. Each instrument is designed to perform a specific function that involves transforming energy into a physical application, such as motion or a change in condition. They might be read as proxies for the painter as transformer of energy, her own and that of her materials, into psychological, emotional, or spiritual motion or change. This hot plate may also be read as an emblem of our own potential to be transformed by the grace of an invisible energy. Celmins’s Hot Plate dates from 1964, the year of Joseph Beuys’s notorious performance at Aachen in which he used a tabletop electrical heater to melt fat in order to suggest that all material remains in a state of spiritual metamorphosis. Like Beuys, Celmins helps us see unexpected significance in the simplest things.

If Hot Plate and Pan suggest artists’ potential to transform their subject matter, Lamp #1 reminds us of the quandaries inherent to some of our assumptions about art [see front cover]. In representational painting in particular, the two greatest hindrances to our appreciation may be our tendency to conflate content with subject matter and our tendency to separate content from form and process. In the case of Lamp #1, our viewing activates the content formed by the union of the subject matter and the process by which it is manifested. We turn Lamp #1 on by looking at it.

Lamp #1 resists being read; its double gooseneck has an alien appearance; it seems to stare back at us like an extraterrestrial with eyes perched on tentacles. The dual focal points divide our concentration. This may be a reminder of the work’s oscillation between depiction and perception, between the painting as something to look at and something to see by. (Neither bulb is lit, and the lamp is instead illuminated by an unseen overhead light source.) After examining Lamp #1, we seem to know less about the lamp than we did before. The heightened attention Celmins pays this humble lamp reminds us that this is a universe of visual experiences that are perhaps more complex than we can fully comprehend.

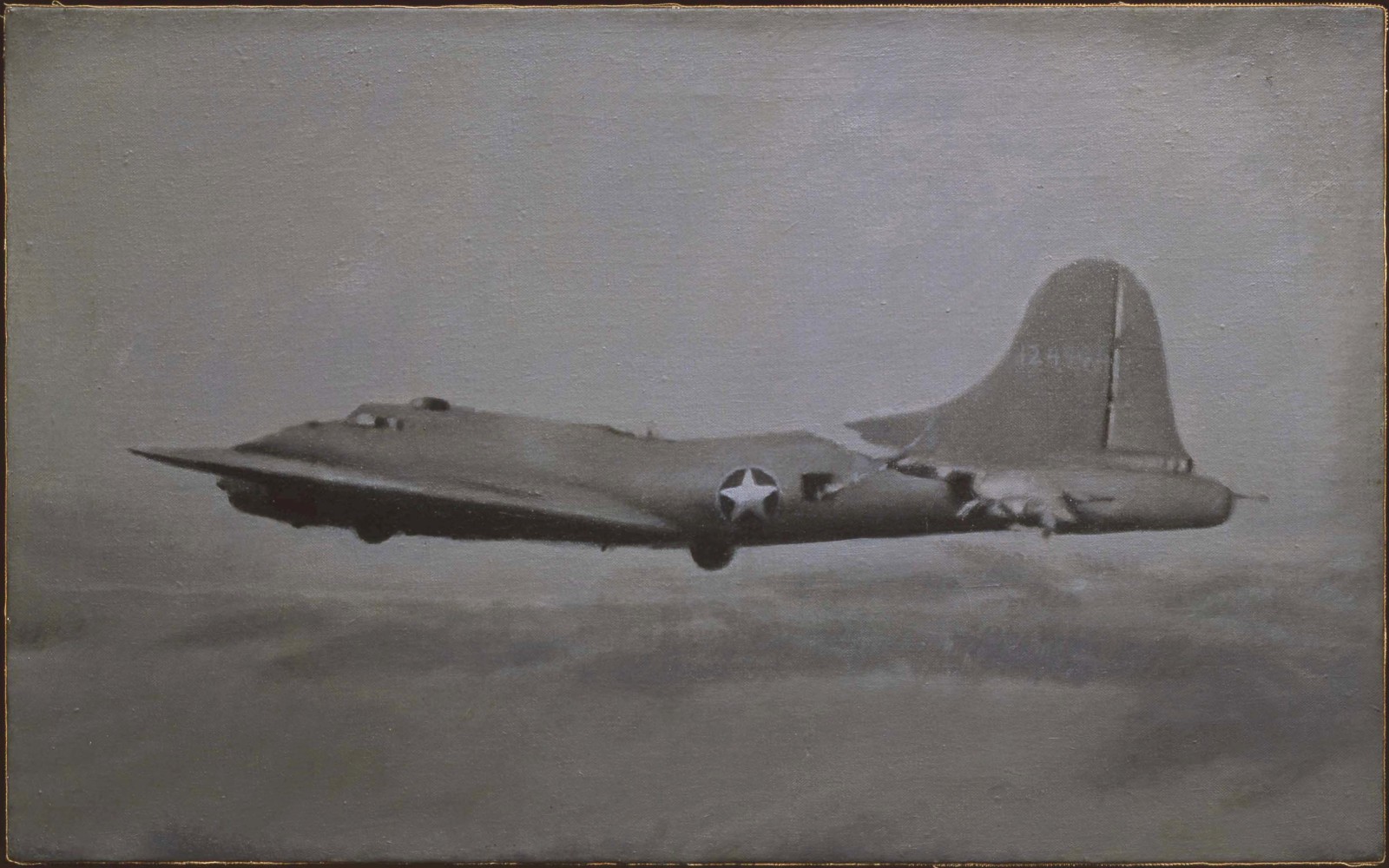

In 1965, Celmins shifted her attention to paintings laden with potential violence, such as one of a World War II-era bomber, the Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress” [see Plate 3]. These works have been read as echoes from her early life, when she and her family fled the Soviet invasion of their native Latvia through Germany to the United States. (In light of these more threatening later works, and of her family’s history, Celmins’s early electrical still lifes divulge a more ominous undertone. The lamp becomes a device for interrogation, while the hot plate and heater evoke even darker associations.)

The problem with reading Flying Fortress through Celmins’s biography is that neither meaningfully contributes to a deeper understanding of the other. But the biographical information is tantalizing, since Flying Fortress contains almost no visual information to aid us in our interpretation. The plane appears fixed in midair. Celmins has reduced the painting’s color and tonal range so that, in a revocation of Renaissance chiaroscuro, space and object are compressed into a single picture plane that coincides with the painting’s surface. The implied movement of the plane from right to left foils our tendency to read the painting like the page of a book, from left to right. Instead, our reading becomes a drag on its momentum. The shadow on the plane’s underside gives it a visual lift, while the weight of the blank space above holds it down. The canceling factors set the plane in the painting’s center, like a plastic model on a shelf. A cloud-like form even provides a sort of shelf on which the plane seems to rest.

Flying Fortress’s problems as a picture come into focus when we recognize that it is based on a photograph. (In fact, Celmins worked from a reproduction of a photograph she found in a book, so there are two degrees of mechanical reproduction separating the plane from the painting.) By severing the photograph from its context, Celmins signals that her concern is not so much with the information it can provide as with how that information is conveyed by the camera’s eye. In Flying Fortress, we are presented with an image of a plane with unidentified contents, on an unknown mission, in an unspecified time, place, and direction. Like the hot plate with nothing on it, the Flying Fortress is an agent in search of impact. As we search the image in vain for clues that will satisfy our curiosity, we are made to see as the camera sees, wide-eyed and dumb.

Critics have suggested that Celmins has employed photography to critique painting—and that she has used painting to critique photography. Nancy Princenthal notes that Celmins’s painting “makes photography…seem hopelessly artificial.” Celmins’s work of this period reflects a recognition that the principal difference between photography and painting lies not in the mechanics of reproduction (that one is endlessly and mechanically printable and the other is unique and handmade), but rather in the method of seeing that each medium proposes (that the camera’s eye sees differently than the painter’s eye). The camera’s eye operates mechanically; it sees instantly and without prejudice or personality. The human eye sees in time and, in communication with the brain, attempts to categorize visual information.

In Flying Fortress, Celmins explores the impact of the camera as an intermediary for our experience of reality. She directly addresses the differences between mechanical and perceptual seeing. We may accept the camera’s increasingly ubiquitous presence to the point of adopting its method of seeing without attention to its effect on us. Celmins’s work, from the early trompe-l’oeil still lifes to her most recent seascapes and spider webs, reflects a strategic approach to the deep interrelationship between how we see and who we are that underlies one of the most urgent defenses of the human value of the visual arts.

A limitation of Celmins’s art between 1965 and 1967 is that it attempts to challenge photography on terms that seem to favor the camera. Specifically, it organizes visual information pictorially. In imitating the camera by focusing on a single subject seen in one moment and rendered without commentary, Celmins’s paintings offer conceptual propositions on issues of representation and perception. Beginning in 1967, with a period in which she focused principally on drawing and printmaking, Celmins shifted her strategy. In her seascapes, desertscapes, starscapes, and webs, she sees, and causes us to see more actively, in a method of perception that recreates the way the human eye works. Even though these later images are still based on photographs, the drawings and paintings trace the human eye’s process of perceiving, measuring, delighting, and scrutinizing.

Celmins now lives in New York, but she came to artistic maturity in southern California. She shares concerns with issues of memory and perception with west-coast space and light artists like James Turrell and Robert Irwin, who was one of her professors at UCLA. Celmins once told the Los Angeles Times: “The one thing I got from Los Angeles was a spatial interest that is not like that of a New York artist.”

Between 1967 and 1985, Celmins set painting aside and began making drawings of the ocean. She may have turned to drawing, a medium she associates with thinking, as part of a strategy of narrowing her art in order to examine her own creative and perceptual process. Around this time, she became friends with Turrell, who was then experimenting with quartz halogen projectors to cast light into corners of dark and empty rooms to create the illusion of cubic forms hovering in space. Using vastly different methods and materials, the two artists were and are engaged in similar inquiry into forms of spatial illusion that generate perceptual experiences.

PLATE 4. Vija Celmins. Untitled (Big Sea #1), 1969. Graphite on acrylic ground on paper. 34 x 45 ¼ inches.

For Celmins, this content first manifested itself in drawings of seemingly immeasurable oceanscapes based on photographs that she had taken herself. In Untitled (Big Sea #1), we are presented with a marvelous, almost dream-like vision of a silvery gray sea without horizon or shore [see Plate 4]. The work is a graphite drawing on paper that has been prepared with an acrylic ground. This ground creates a tight surface on which the graphite (incidentally a conductor of electricity) is suspended by its own friction. This drawing’s composition, to the extent that we can discern it, operates according to two principles that govern pictorialism: that unless directed otherwise we read an image from the lower left toward the upper right, and that the eye is drawn to areas of light, which in this work are unmarked areas of the acrylic ground. Here Celmins establishes a grayscale (a visual device that measures tonal value from black to white) with the darkest areas anchoring the image at the lower left and the lightest areas lifting us to the upper right. As the image gets lighter, almost as if the picture were evaporating, it seems to rise as much as it recedes; in fact it only recedes because our mind tells our eye that it should see an indeterminate depth of space. We move across the drawing’s surface carried by a seemingly uniform repetition of marks that extend to all the image’s edges. Each wave is rendered in a series of infinitesimal marks that can only be seen under magnification. Magnified, the waves dissolve into a sea of marks.

Although Untitled (Big Sea #1)’s waves’ crests and valleys suggest a choppy sea, without other points of reference we have no way of measuring their proportion and motion. As a result, this seascape reads as perfectly serene, as if Celmins were drawing the ocean according to the conventions of a still life rather than a landscape.

If perception involves both receiving stimuli through the eyes and processing that information in the mind, Untitled (Big Sea #1), challenges us on both counts. In its seeming absence of gesture, this drawing might suggest an erasure of the artist’s touch, but this is not the case. Celmins’s touch is made nearly invisible by her unwaveringly patient working process; her marks are almost too tiny to be seen. If there is, as Celmins insists, a correspondence between an artist’s mark-making and process of looking (both at the painting in progress and the object being painted), the gradual dissipation of perceptible evidence of Celmins’s mark-making from Pan to Night Sky #2 suggests that her perceptual abilities have become, over decades of diligent practice, refined to the point where we cannot see the level on which she operates. Lest this barrier discourage us, the resident beauty of Celmins’s art encourages us to learn from her perceptual and conceptual skills. If we allow them to, the new ways of looking we learn from Celmins may extend into every part of our physical, emotional, and spiritual lives. It is this subtle but significant challenge to how we see, and by extension live, that separates Untitled (Big Sea #1) from other well-made contemporary seascape interior decoration.

Celmins’s seascapes have been described as “unbounded” but this is not precisely the case. Both the sea and the drawing are necessarily bounded. Water will flow until it meets a boundary. Similarly, as Hans Hofmann observed in The Search for the Real, the two-dimensional work of art finds definition through the relationship between its internally exerted forces and those established by its perimeter. The work’s internal forces also react with each other in a process that Hofmann called “push and pull.” In a well-balanced composition, these elements hold each other in check. By minimizing push and pull within her image, Celmins allows the entire image to act as a united force against the drawing’s literal boundaries.

Celmins has described her working process as “making the image and mark develop together.” She seems to be contrasting her method with a process in which an artist imagines a picture and then makes marks that realize that image. In that case, in her opinion, the mark is almost perfunctory. In her working process, the pictorial elements develop over time in equilibrium with the literal elements. This impacts viewers’ engagement of a work like Untitled (Big Sea #1). By pursuing a dialectic of pictorial and literal elements, Celmins encourages a visual experience that establishes a link between the viewer’s person, place, and perception.

Celmins next turned her gaze to the parched and dusty surfaces of rocky desert landscapes and cosmic galaxies. This trio of primal motifs—water, earth, and air—has allowed Celmins to explore her interest in material surface through subject matter in liquid, solid, and gassy states, each of which finds different translations into the image’s graphite surface. Perhaps more importantly, in her treatment of the sea, desert, and cosmos, Celmins has been able to study perception from different points of view: from above, from straight ahead, and from below. (B.H. Friedman once observed that Pollock had distinct postures depending on whether he was looking up, ahead, or down. For Pollock the act of looking seems to have involved his whole body and being.)

PLATE 5. Vija Celmins. Holding onto the Surface, 1983. Graphite on acrylic ground on paper. 21 x 21 inches.

Arguably, Celmins’s most impressive works are her star fields and galaxies such as Holding onto the Surface [see Plate 5]. With rare exceptions, her expansive cosmic spaces are silent and still, without the implied movement of meteors or comets. Based on satellite images, these luminous skies seem unaffected by the terrestrial light and atmosphere that often cloud our view.

Untitled (Big Sea #1) of 1969 and Holding onto the Surface of 1983 highlight the principal themes and developments of the intervening period in Celmins’ oeuvre. She characterized her project this way: “I like to work with impossible images, impossible because they are non-specific, too big, spaces unbound.” Celmins’s art then becomes a process, for her and her viewer, of grasping this content. She also related the tension between subject and painting this way: “You need a leap of faith to believe that physical [material] you’re working on will become an image that is totally different but also what you expect and what you want.” For the artist, this process is a struggle. For the viewer, looking at Untitled (Big Sea #1) and Holding onto the Surface is an experience of sublime stillness.

Like Untitled (Big Sea #1), Holding onto the Surface is the product of an arduous and meditative process, and one that corresponds to its subject. Like the cosmos itself, the drawing is a blurring of matter and light. The surface of the paper is again covered with a white acrylic that suspends each grain of graphite in its matte surface, creating a visual sensation of pulsating, electrically charged material. There is a reversal here between literal and depicted matter: the areas we read as the deepest, blackest empty space are in fact the most heavily worked, while the forms that we read as stars—the subject of the drawing—are untouched. Beyond any philosophical or spiritual implications that this material-immaterial dialectic suggests, this inversion causes us to shift back and forth between the work’s representational subject and its formal construction. Holding on to the Surface’s illumination comes from deep within the drawing because it was imbedded there as a part of the drawing process, not dabbed on as a last step to create a highlight effect.

Holding on to the Surface is an unusual title for Celmins in that it does not describe the work’s subject. Instead, it may describe the process by which the image is created: the graphite clings to the acrylic ground. In a 1991 interview, Celmins told Chuck Close:

I did a series of images of oceans and deserts using different grades of graphite and pushing each to its limit. I learned a lot about the possibilities of graphite by doing this. Then I moved into the galaxy drawings. Even though you may think they came from lying under the stars, for me, they came out of loving the blackness of the pencil. It’s almost as if I was exploring the blackness of the pencil along with the image that went with it.

PLATE 7. Vija Celmins. Night Sky #2, 1991. Oil on canvas mounted on aluminum panel. 18 x 21 ½ inches.

Exploring this blackness brought Celmins back to painting, a medium that allowed her to build up more strata of surface. Night Sky #2 (1991) and Night Sky #12 (1995-96) are painstaking accumulations of layer upon layer of darkness, each finely sanded between painting, to create a dense matte face that is the fruition and fulfillment of the pursuit of a harmony of form and surface that Celmins began to explore in Untitled (Big Sea #1) more than two decades earlier [see Plates 7 and 8]. Night Sky #12’s pitch darkness enhances the suggestion of infinite pictorial depth out of which the starlight burns with greater intensity. This same opaque blackness prevents us from visually penetrating the painting’s surface. Only the stars, pinpricks in this shield, allow us to move back in space. What we see is both infinite and flat, a paradox that reflects Celmins’s relationship with romanticism, her reservations about pictorialism, and the complicated relationship between the painting and viewer.

While Untitled (Big Sea #1) has a sublime stillness, we should not over-read Celmins’s intentions. She does not seem particularly interested in viewers’ spiritual experience of her work. In the same interview, she told Close that she does not have “that Casper Friedrich tendency to project loneliness and romance onto nature; to contrast nature’s grandness with tiny, insignificant watchers. I like looking and describing…. The meaning for other people tends to be a projection of their own romance.” When Close presents her with metaphoric readings of her work, Celmins repeatedly turns the conversation back to issues of material and process. However, as Hans Hofmann noted in The Search for the Real: “The metamorphosis which takes place when an experience is translated into a medium of expression is…controlled by inherent but limited qualities of the medium. The infinite can be created only on the basis of such a limitation.” It is by fully embracing the boundaries of her art and experience that Celmins is able to stretch ours. While Celmins does not exclude the possibility of our finding metaphors in her work, her approach to the sublime is distinctly understated. Celmins’s expectation that each viewer find his or her own meaning in Night Sky #2 or Night Sky #12 is, in fact, a sort of romanticism in that, rather than being given a secure position in relation to the sublime, each of us must find our own place in her universe. Since we engage Night Sky #2 and Night Sky #12 through our own perceptual prisms, we each of us, to paraphrase a title of a work by Anselm Kiefer, stand beneath our own dome of heaven.

Celmins’s exploration of a post-Pollock conception of space is nowhere more evident and multilayered than in Holding onto the Surface, Night Sky #2, and Night Sky #12. In 1947, the year that he made his most distinct break with Renaissance conceptions of painting, Pollock gave his paintings titles that evoke seascapes and starscapes, such as Galaxy, Reflections of the Big Dipper, Shooting Star, Comet, Full Fathom Five, and Sea Change. Kirsten A. Hoving has described these works as having “a new sense of painting as a telescopic vision of an expanding cosmos.” She adds that Pollock’s technique of pouring paint down onto canvases on the floor:

may have helped him come to this new understanding of space. By breaking away from easel painting, Pollock was also breaking away from a horizon-oriented space that conformed to the erect, vertical artist…. Pollock proposed a new conception of space, of looking up, rather than out, to the night sky without vanishing points or human referents.

This is important because it is this break with a horizontal conception of space (both within the painting and, since the painting is a proposal of a strategy of seeing the world, beyond) is what elevates Pollock’s work above that of other abstract expressionists. Part of Celmins’s work’s urgency and value is her brazen application of a Pollock-informed conception of space to representational painting.

Perhaps the greatest appeal of Celmins’s art is that she applies a technique of hard-edged realism (one that suggests visual clarity and conceptual rigor) to soft-edged subjects (water, stars, sand, webs). Celmins’s work has an unassuming simplicity and intimacy that draws us in and a lack of specificity that keeps us at a distance. Her subjects are readily recognizable and rendered with an exacting clarity. At the same time, many of these works read as abstract. In Night Sky #2, an innumerable myriad of dots of light puncture a field of blackness. The absence of other points of reference draws the presumably distant stars toward the painting’s surface. We have no way of measuring pictorial space within the image, so terms like closeness and distance have diminished meaning. As Night Sky #2 seems to shift in and out of focus, it becomes hard to look at.

Part of the paradox of our relationship to Celmins’s paintings lies in their subject matter. Unlike the ocean, the cosmos, as far as we can see and know, is not only boundless but expanding in ways that confound our imagination. Hofmann noted: “A glimpse heavenward at a constellation or even a single star only suggests infinity; actually our vision is limited. We cannot perceive unlimited space; it is immeasurable. The universe, as we know it through our visual experience, is limited.” Celmins’s rapturous works stretch our creative perception from the literal material present to the farthest reaches of the universe. These cosmos paintings seem to be devoid of constellations; none, in any case, are mapped out. Navigating these pictures of infinity, we have no horizon, no vanishing point, no perspective, no up, no down, no left, and no right, no movement, no beginning, no end. They provide us with none of the internal, formal, or narrative, structure that we typically employ as aids in reading a painting’s content. If Celmins’s trompe-l’oeil still lifes of 1964 explored the microcosm of the artist’s practice in the studio through a juxtaposing of the abstraction of the artist’s touch with the specificity of certain objects, her more recent works set us adrift in edgeless macrocosmic expanses without allusions to herself or points of references that would give us a framework with which to measure our own perception.

Celmins’s cosmic and seascape works may be as taxing for the viewer to look at as they are for the artist to transcribe. In a culture that actively reduces our attention span, Celmins cultivates the viewer’s slow concentration. Even after we have studied these paintings meticulously, it can be difficult to picture them in our memory with satisfying exactitude. It’s not that these images have more visual information than we can remember, but rather this information exists within a narrower range (of subject and form) than we can readily differentiate, measure, categorize, and remember.

These works further serve as a means of measuring our perceptual process in that, from across the room they look abstract. Night Sky #12, which is only 31 by 37 ½ inches, appears to be a soft monochrome, potentially with all of the associations of infinity that this evokes. As we step closer, it reveals itself as a highly detailed photorealistic rendition of cosmic space. Intrigued by this recognition, we may draw closer to inspect Celmins’s creation only to find that, up close, the image dissolves, like a collapsing star, into an abyss of abstraction. Like the cosmos, her work has a cycle of growth and collapse. This cycle calls our attention to our own physical relationship to the work and how we variously perceive the same subject from different points of view.

Celmins’s art often comes into clearer focus when viewed in series. (The 2008 Carnegie International exhibition contained nine works from her Night Sky series.) Celmins noted: “I tend to do images over and over again because each one has a different tone, slant, a different relationship to the plane, and so a different meaning.” By comparing Night Sky #2 and Night Sky #12, we are able to better describe them both. Because it has less mid-tonal range, Night Sky #12 appears to have greater clarity than Night Sky #2. However, this clarity comes at a cost to the viewer in that it flattens spatially into an undifferentiated field of white pinpoints. Night Sky #2’s haze actually provides areas that can be read as a nebula and thus be distinguished from the rest of the painting. This allows the viewer to focus on and map the painting’s illusion of space with greater clarity.

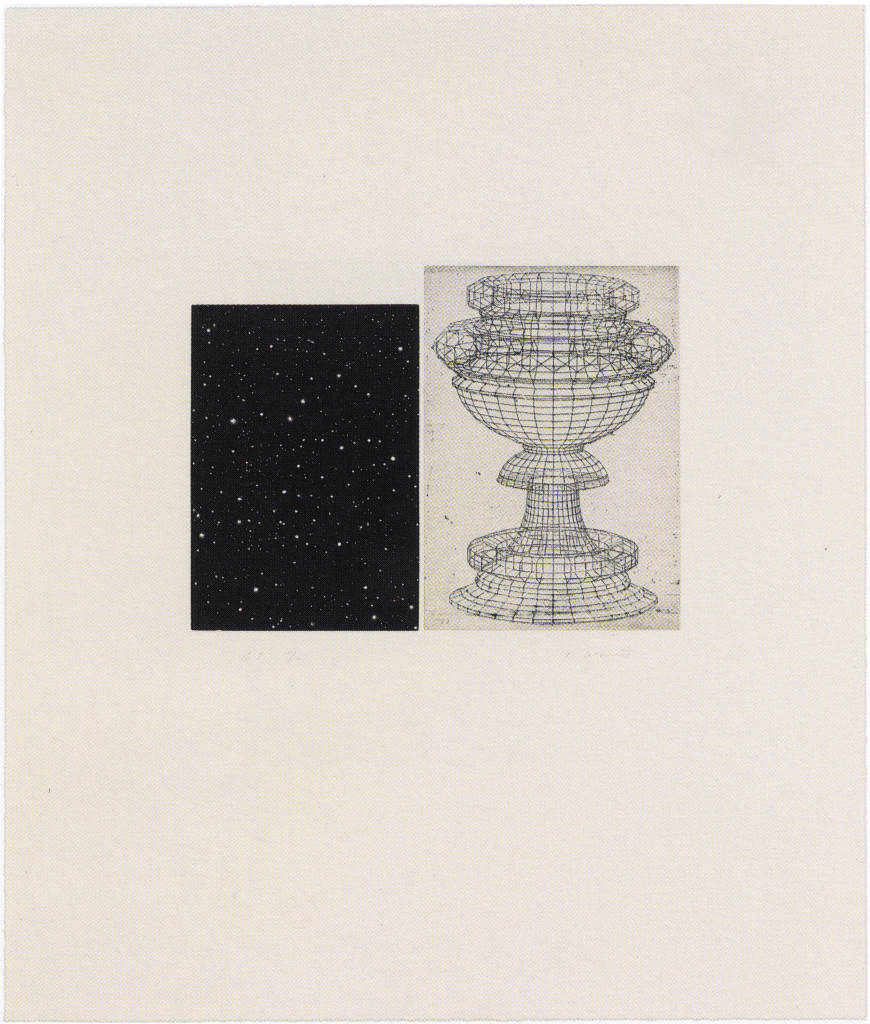

If Night Sky #2 and Night Sky #12 are part of Celmins’s strategic challenge to the pictorialism that has shaped western painting since the Italian Renaissance, her own awareness of this is highlighted in Constellation-Uccello [see Plate 6]. This print sets a star field side-by-side with a rendering of a chalice by Paolo Uccello, a pioneer of quattrocento pictorial space, which Celmins transcribed from a reproduction she found in a book. The black star field is smaller than the Uccello but, due to its visual density, balances the overall composition. Contrary to the title, there is no constellation mapped out in the star field, nor is there a picture of the man Uccello. Constellation-Uccello is a proactive rather than descriptive title, implying that we should read the star field pictorially as a constellation and the chalice conceptually as a surrogate for Uccello.

Uccello himself encourages our natural tendency to search a field of unconnected visual information for means of organizing it. Here as with her other cosmos imagery, Celmins frustrates this effort. She seems more concerned with what the conceptual foundations of the starscape can bring to our reading of Uccello’s drawing. For example, on closer inspection, we may note that some parts of the chalice are transparent and some are not. There is no apparent logic to this inconsistency other than that Uccello had come to the limits of his perceptual and conceptual imagination—just as we do before Celmins’s work.

Not only has Celmins copied Uccello’s drawing, she has transcribed most of the other marks and discolorations of the paper itself. While we, in looking at Uccello’s original drawing, may mentally Photoshop these blemishes, Celmins’s dedication to observation and recording compels her to treat these imperfections with the same attention she gives the drawing itself. In the context of the attention that Celmins has paid them, and paired with a field of stars, these seemingly irrelevant marks read like black stars in an off-white sky, with the chalice acting as a constellation, transforming the microcosm into a macrocosm.

Beyond the effect that these two images each have on our reading of the other, Constellation-Uccello may have implications for our understanding of Celmins’s overall project. Without breaking with representational image making, Celmins critiques the very premises of pictorial space. In his landmark text The Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space, John White cites clarity of form and space as the hallmarks of an art designed “so that the eye is not confused…and can apprehend the whole in an instant.” Is the cosmic side of Constellation-Uccello more or less apprehendable than the chalice? The two sides may be equally readable, but on different terms.

Constellation-Uccello may reveal as many similarities as differences between Celmins and Uccello. The two share a painstaking devotion to their art. Giorgio Vasari criticized Uccello for allowing his attention to perspective to distract him from other things, both in art and life. Celmins’s process is likewise one of patient and persistent concentration and devotion. In a fast-paced culture that tends to move like a flat stone skipping across the surface of things, Celmins’s work, as Adrian Searle notes, makes us “aware of the silence of the studio, of the weeks, months, and years spent drawing and painting the same things, attempting to fix their presence, finding, losing, and re-finding them again in the space between the artist’s hand and her eye.” Celmins’s work comes into increasing focus as one considers it in wider historical frames of reference. That she has maintained an engagement with such a limited repertoire of subjects over such an extended period with such vigor and freshness is a testament both to her own patient devotion and the real depth of her artistic project.

Celmins and Uccello have also both avoided allowing their passions to become overly abstract or academic. White describes Uccello as “inquiring into the nature and validity of the new method, and weighing it against his experience of the natural world.” White suggested that, while artists of Brunelleschi’s generation laid out the principles of perspective as a mathematical abstraction and were resigned to a certain degree of inconsistency when applying them as a method of seeing and rendering nature, Uccello was intent on resolving and applying perspective not only to image-making but to looking at nature.

Like Uccello, Celmins looks at nature with a heightened awareness of her own strategies of charting forms and space. She selects ungraspable motifs, such as the sea, cosmos, and spider web, that challenge her perceptual skills, provide her with opportunities to practice her exacting method of inspective image-making, and afford her opportunities to examine the premises of her art.

Web, like its subject matter, evidences a calculated and patient process [see back cover]. The late John Russell described Celmins as having “the perseverance of a silkworm and with a surgeon’s steadiness of hand.” Her marks are often visible only under magnification; like the spider, she entangles the viewer by working beyond our perceptual spectrum.

In Web, Celmins magnifies the web’s natural geometry and suspends it tightly across the painting’s frontal surface, emphasizing structural correlations between the spider’s engineering and a painting’s construction. A web, like a painting, depends on boundaries for its existence, and Celmins emphasizes this by attaching the web’s anchoring threads to the painting’s edges. Web’s structure and image cannot be separated. Both the painting and the web begin with a measuring of the parameters to be covered. Across this surface, a design is plotted and a form is constructed that sets a trap to capture insects and viewers alike.

Celmins’s web is unevenly lit; some of its upper portions are cast in shadow. This gives the painting a sense of organic life and craftily disguises the clinicality of Celmins’s exacting process. The web seems to have dust or insects caught in it. As these catch the light, they read as stars or galaxies and reinforce the association between the web and a constellation or cosmic map. The cosmos and web both operate beyond the extremes of our spectrum of perception. The cosmos is larger than the eye can see, the web more intricate.

The web, at least the idealized web, is a natural form that, when laid across a picture plane, strangely resembles the abstract lines of perspective converging to a vanishing point, with each successive receding plane being delineated by a smaller circle. As an abstract painting, Web is a chart of pictorial space and analytical thought. But as a picture, the web is a perfectly flat form that clings to the painting’s surface with no promise of space behind it, suggesting an intuitive approach to representational painting. The web alludes to a strategy of organic growth, transformation, and process that continues to develop the themes established in Pan and demonstrates the overall unity of her oeuvre.

Celmins’s endurance and originality—as well as her limited but firmly established reputation—may be attributed to the fact that her work does not fit comfortably into any art historical corrals (mostly all-boys clubs) such as Pop Art, photorealism, minimalism, conceptual art, or even Earth Art, each of which she engages to one degree or another. That Celmins works slowly and without fanfare adds to her reclusive reputation. Elevating her work above the ebb and flow of art world trends, Celmins has maintained a laudable steadfastness of vision. The works exhibit a consistency and confidence that is the result of an intense self-criticism and even some periods of self-doubt.

Upon being arrested, the museum guard-turned-iconoclast told police, “I didn’t like the painting.” His comment reminds us of prevailing attitudes often brought to art—and of how Celmins challenges them. According to the I-don’t-know-much-about-art-but-I-know-what-I-like school of criticism, art should either please the eye (“That’s a pretty picture”) or fool the eye (“How did she do that?”). Night Sky #2 exasperates both these desires. As a picture, or a rarified form of interior decoration, it is unsatisfying in its lack of pictorialism. And despite the labor involved, it appears to be effortless. As a work of art, Night Sky #2 presents a strategy by which painting, in its content and form, may contend with modern experience by presenting us with methods of seeing, stretching our capacity to perceive. This makes the work’s destruction a small but significant loss to our human experience.