I CAN’T SAY I EVER TRULY APPRECIATED the landscape of the southwest desert until I started going out there myself on a regular basis. Really, you’ve got to get out of the cities and towns. Santa Fe is cute, sure. But you’ve got to go further than that, out into the zones of land stretching into burnt red horizons. You’ve got to get into the spots where the cliffs shoot out of the land and the swirling colors emerge from the faces of those cliffs. You’ve got to see the mesas in their resolute flatness. Why is a mesa so deeply satisfying? No one knows. It’s a mountain that suddenly changes its mind midway to the sky and decides to become the ground again.

That land out there—seeing that land and trying to make us see it too, that’s what made Georgia O’Keeffe into a great painter.

It all started in flowers and other plant parts. That’s true. The flowers started it.

The continuity stretching from the earlier flower and plant paintings to the landscape work in New Mexico comes from O’Keeffe’s lifelong obsession with looking at things. I mean that quite literally. How do you look at a thing? How do you see a thing? Well, you just look, don’t you? But O’Keeffe’s answer is, “No, you don’t just look, because you don’t know how to look.” So what’s the difference between looking in the normal way and looking in the O’Keeffe way? Much of it has to do with time. O’Keeffe liked to look at things for a long time. She’d stare at a single flower over and over again, hour after hour. We think we know what that means. But do we? I suspect the actual experience is crucial here. That’s to say, don’t assume you know what it means to look at one thing hour after hour unless you’ve done it. I’ve done it, sort of. I stared at a flower once more or less without interruption for over an hour. It was immensely difficult for the first twenty minutes or so. Then something changed. My vision started to surrender to something else. Everything suddenly slowed down and intensified. I started to see the flower as a whole, as well as the tiny individual parts, simultaneously. A kind of meditational state kicked in. My vision became a form, almost, of physical touching. It was sensuous and sensual, which is why all the critics who’ve talked about the sensuality of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are not completely wrong. There’s a vibrancy to the flower paintings for the very reason that there is a vibrancy to the experience of deep looking. Her paintings are the rendition, in paint, of this experience. Sex is simply one of the many things that emanate from the deep, sensual core of living things when you get to looking at them.

One way to describe what O’Keeffe did with landscapes is to say that she was trying to figure out a way to look out at the horizon and to see things out there as deeply as she was able to see things like flowers and plants up close. In her earlier landscapes, like Lake George, Autumn (1927), she’s still trying to render the whole scene—foreground, middle ground, background, the continuity of looking that happens when we scan the field of vision before us. There’s a tradition in landscape painting going back to the Renaissance that is concerned with how to render the rich depth of a landscape on the flat surface of a canvas. Yet what Georgia O’Keeffe realized, along with plenty of other modernists, is that this tradition had to be reversed in order to capture the individual objects again. The “scene” of the landscape has to be broken down to activate the power of deep looking. It’s relatively easy, though still damn challenging, to engage in deep looking when you’ve got one single thing right in front of your face. But O’Keeffe wanted, needed, to take on the harder challenge. How do you move the eye and mind out into the wider world without losing the intensity of those luminous flowers?

Georgia O’Keeffe. Oriental Poppies, 1928. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

It should be noted that this problem of close looking at distant things could not be solved by photography. One of the nastiest things that critics of Georgia O’Keeffe (people like Clement Greenberg and later Robert Hughes) did to her work was try to subsume it under the photographic project of her husband. It’s true, of course, that Alfred Stieglitz was much O’Keeffe’s elder, and that he had a definitive impact on her art. It’s true, also, that she was intrigued by the view of objects from behind the lens of the camera. The influence of Paul Strand, Stieglitz’s protégé and O’Keeffe’s on-and-off love interest in her younger days, must also be mentioned here.

But the insinuation that O’Keeffe was simply copying Stieglitz and Strand’s photographic close-ups in the medium of paint misses the whole problem that O’Keeffe was trying to solve. She was, to overstate the obvious, interested in paint. She wanted to make paintings. The power of a painting is that it can, potentially, render a picture of a thing being looked at that shows how the thing is transformed by the looking. Photography sets up a different dynamic, precisely because the photographer, in creating an image, must contend with a second, mechanical eye, the eye of the camera itself.

O’Keeffe’s close-ups, if we can call them that, do not quite have the look of close-up photographs. Even the iconic flower pictures, pictures that come closest, have an entirely different feel to them, difficult to describe but impossible not to see. A painting like Jimson Weed from 1936, for instance, is on the face of it an extremely realistic detailing of four jimson weed blossoms. But you’d never mistake it for a photograph. Why not? Maybe it’s the resonance between the curvy lines in the blossoms and the veins on the leaves in the background. And the deep background of the painting, while vaguely sky-like in its soft blue color, is something not quite of this world. Or look at the leaves in the top left of the painting. O’Keeffe has played with the lines of darker and lighter green to the point where the painting almost reads as a landscape. The overall effect is psychedelic, not obviously at first, a subtle psychedelia, but one that becomes more assertive as you look.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Jimson Weed, 1936, 70 × 83.5 inches, Oil on canvas. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The camera was essentially useless to Georgia O’Keeffe for the simple reason that she didn’t like the imposition of the second eye. Looking through the lens, for her, amounted to breaking the spell of deep looking. It created an extra layer of mediation. That’s the simultaneous beauty and strangeness of the camera, something that later artists like Bernd and Hilla Bechers and their Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) would use to brilliant effect. But O’Keeffe was not interested in that kind of look or feel. O’Keeffe’s interest in objects came from the desire to show what happens to them when subjected to intense scrutiny. Deep looking changes things. The subject and the object interpenetrate.

O’Keeffe was always a Romantic in this sense, and a mystic. Of course she hated all those sorts of labels. So, call her what you like. The point is that in O’Keeffe’s work the boundary between subject and object dissolves before our very eyes.

O’Keeffe came to her fundamental breakthrough by essentially removing the middle ground in her landscapes bit by bit until she’d dispensed with it almost completely. In many of her paintings and sketches, she just brings the thing she’s looking at—a crevice or canyon or rock structure or mesa—right up into the foreground even though, in reality, she is painting it from far away. Small Purple Hills (1934) is a good example. She did away with all the reference points that would give us any visual context for relative distance, depth of field, anything like that. The hills are just pressing right up against the canvas, and right up against our visual experience. It’s downright aggressive, like the Cézanne paintings where tables and chairs and vases and bowls of fruit are practically hammering at our eyes from the cockeyed vertiginous space of the canvas.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Small Purple Hills, 1934, 16 × 19 3/4 inches, Oil on panel. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, 2006.

So, to see things, to see one thing, you have to remove a lot of the other stuff. That is the principle by which O’Keeffe lived her life, and the way in which she painted. She loved the desert for this very reason. There’s a principle of removal out there. Just get it down to a couple of things and then really concentrate on those. O’Keeffe turned her own person into a version of that too. She once told Calvin Tomkins, who went to visit her in New Mexico before she died and wrote a piece about it for The New Yorker, that she would have liked to push the past entirely out of her life. Pushing things out, slowing things down, removing as much as possible. Have you ever noticed that there isn’t a single human being in the entire painting oeuvre of Georgia O’Keeffe? Not that I know of, anyway. Perhaps humans were already too multiple for her just by being human. Or perhaps she didn’t have that specific skill required to make something simple of another person. So she tried over her long life to simplify herself, to make of herself something solid and unvariegated, like a piece of ancient stone. All the famous stories of the mature O’Keeffe are about her being harsh, about her denial of the basic human niceties.

There is a canceling that happens here, an obliteration. And in the wake of this obliteration, a new fullness.

We’re talking about removing everything that gets between. This is an art of extreme closeness. The closeness here should not be thought of primarily as physical, though it is that, too. One thing O’Keeffe liked about the desert is that you can feel very close to something, say the mesa peak of Pedernal, without being physically close to it at all. The strange thing about the mountains of the southwest desert is that distance gets all confused. You can approach a place like Pedernal for miles and miles and never seem to get closer. Sometimes it can seem as if you’re getting closer when, in reality, you’re getting farther away. And vice versa and back again. These are the tricks and mysteries of space and distance and perspective in that landscape. O’Keeffe seemed drawn to exactly these experiences which, to her, were not tricks at all. Something true about the world was being revealed.

The philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin once wrote a brief fragmentary thought later collected and published as “The Great Art of Making Things Seem Closer Together.” The fragment of text concludes with the following two sentences: “The great traveler is the person who passes through cities and countries with anamnesis; and because everything seems closer to everything else, and hence to him, since he is in their midst, all his senses respond to every nuance as truth. The distanced Romantic is as ignorant of this as the Positivist.”

The great project of O’Keeffe, out there in the desert, was a project of distances, getting the correct distance. The correct distance is one of almost infinite closeness. But how do you get so close that the closeness does not dissolve into blurriness? That’s the problem with trying to get very very close to something, to anything. Too much closeness is just as obscuring as too much distance. But maybe there is a form of closeness that has exactly the same feel as extreme distance. We are inching, now, into the realm of the absolute.

At some point, I think toward the later 1930s, O’Keeffe realized that she could replace the lost middle ground in her paintings with the singular objects, the plants and flowers, of her other paintings. The singular deep looking and the landscape deep looking could be merged. Why not? She painted, for instance, Red Hills and White Flowers in 1937. The red hills are right there. And the flower is right there. It’s almost like a grade-school primer on deep looking. “Get how I’m seeing the flower in its utter shining singularity? Well, look at the red hills in the same way.”

Georgia O’Keeffe, Red Hills with Flowers, 1937, 20 × 25 inches. The Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Hortense Henry Prosser.

© 2018 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

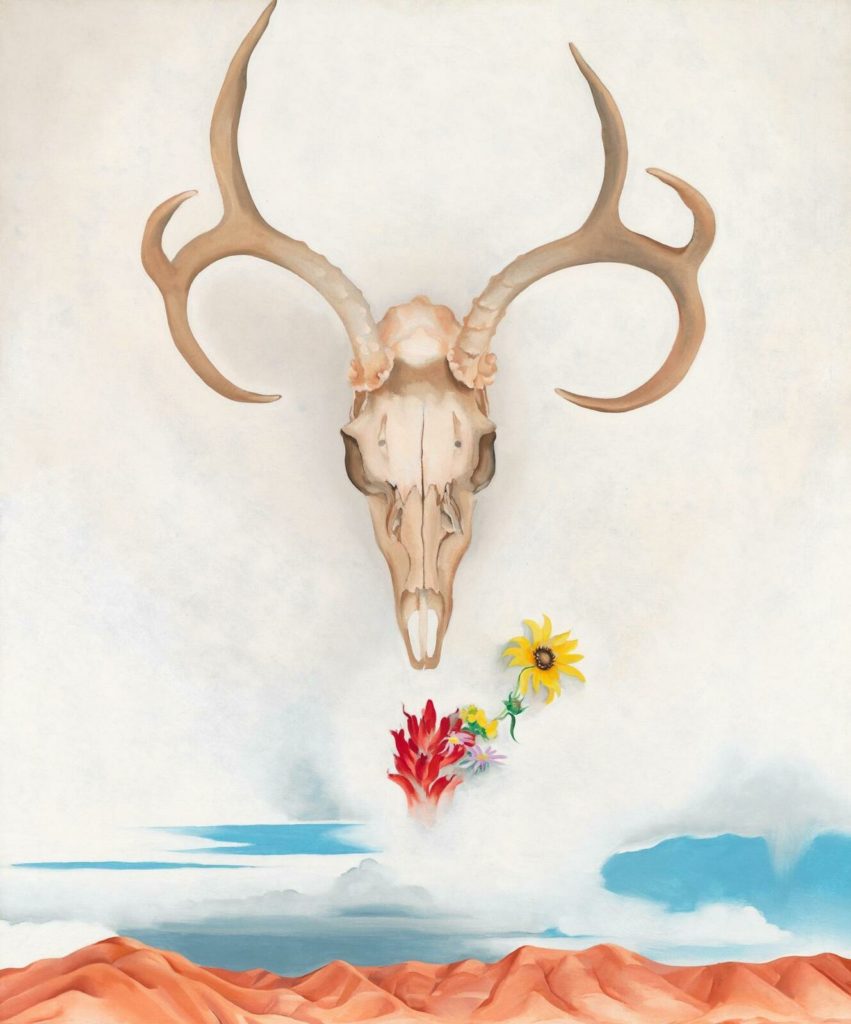

Have you ever stumbled across a bone or a skull while walking in the desert? Time and focus really snap into place when that happens. “Holy shit,” you say to yourself, “there’s death right there in the dirt in front of me.” The physical presence of death makes you feel suddenly more alive. Clearly, Georgia O’Keeffe experienced something similar. So, these skulls and bones, too, became a part of her art. These were objects already showing us how to look, how to have a genuine experience. One day, she realized that she could put those skulls and bones in the paintings without messing up the singular, no-middle-ground aesthetic space of the canvas she’d already achieved. She just plopped the image of the deer skull, or whatever, into the infinite spacey-non-space of her paintings, and it worked just fine. This sort of painting isn’t realism anymore, not traditional realism. It is mystical realism.

Take a painting like Summer Days (1936). The hills are in the background. Or is it the foreground? They are far away, or maybe super close. Does it matter? And then the skull and the flowers. In the sky. But not really in the sky. Just there where the sky is. Like the sky. Totally present and totally distant, just as the sky is. As the sky as the hill as the skull as the flower. Unique but interchangeable, individual and absolute.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Summer Days, 1936, 36 1/8 × 30 1/8 inches, Oil on canvas. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Calvin Klein. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

One of the stupidest things Robert Hughes ever said was that O’Keeffe’s “paintings of skulls and pelvises in the landscape mostly verge on kitsch surrealism.” He failed to understand the project. He failed to understand the problems in painting and looking that O’Keeffe was trying to solve. That she did solve.

In 1937 Georgia O’Keeffe painted a picture called From the Faraway Nearby. Interesting title, is it not? I’d like to rest my case on that title alone. She knew what she was doing. She was after what Ruskin called “the deep infinity of the thing itself.” There are, I suppose, three things in From the Faraway Nearby. There are the hills. There is the skull. There is the sky. In this painting, we are in complete and total contact with these three things. And we are also as profoundly distanced from them, as utterly confounded by them, as we could possibly be. And, also, there is a silence, emanating from the very painting itself.

Normality, our normal everyday reality, exists in the interstice between extremes. What would it be to create a form of art, a form of visual looking that collapses the space of normality, the middle space, and presents only the extremes? Extreme distance and extreme closeness presented, in a sense, as one. Take, if you will, O’Keeffe’s Hollyhock Pink with Pedernal (1937). Here is the removal of any meaningful middle ground. Normal looking is taken out of the equation. Instead, we see the mountain as we see the flower and we see the flower as we see the mountain. Both “things” have jumped out of their context and confront us as luminously, strangely, and completely there. So incredibly simple. So simple, in fact, that very few people who look at the painting allow themselves actually to see it.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Hollyhock Pink with Pedernal,1937. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

One day, not so long ago, I went to see that place, to see O’Keeffe’s mountain, to see Pedernal, the object out there in the world about which O’Keeffe once famously proclaimed, “It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.”

My first thought upon gazing out at that peaky mesa top looming quietly in the distance was: O’Keeffe’s Pedernal is better. The Pedernal of real life just doesn’t quite stand up to the Pedernal of O’Keeffe’s paintings and drawings (she painted it something like thirty times, and made countless drawings and studies). Pedernal, in short, does exist. But it exists on O’Keeffe’s canvases first. All the other Pedernals, including the one that can be located out there somewhere in the southwest desert of New Mexico, are now tertiary. O’Keeffe’s paintings do not represent Pedernal. They create it.

Morgan Meis is a writer living in Detroit. Winner of a Whiting Award, his most recent book is The Drunken Silenus (Slant).